An older post from Lawrence W. Reed at the Foundation for Economic Education outlines the low points of the Great Depression and debunks a few widely held myths about that cataclysmic economic era:

Phase 1, the Federal Reserve and the end of the Roaring 20’s:

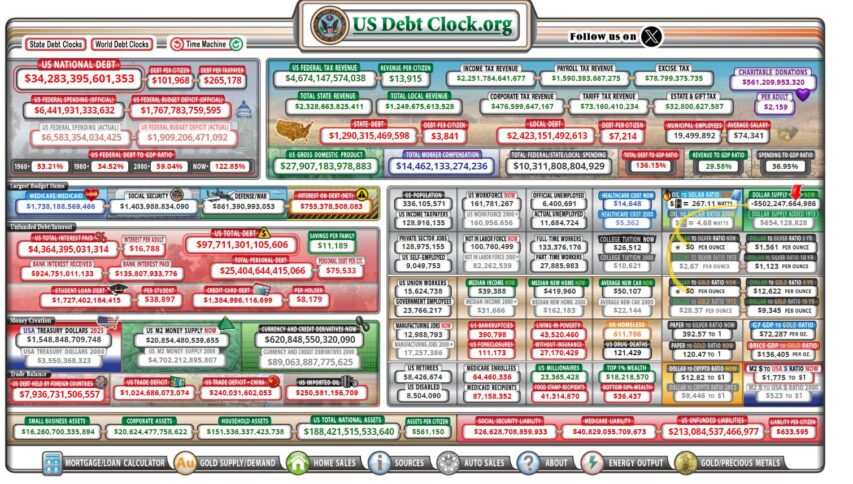

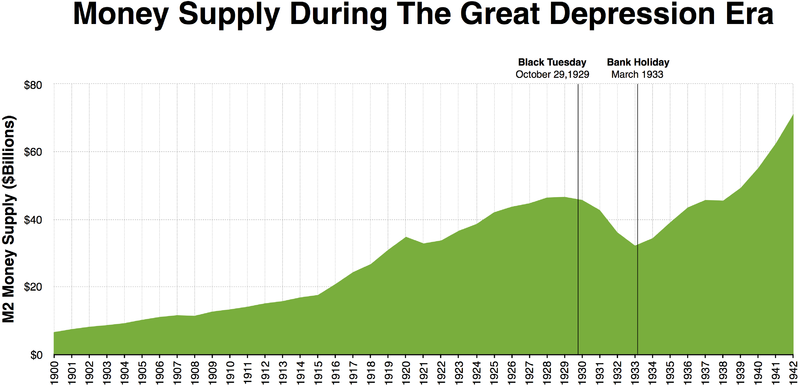

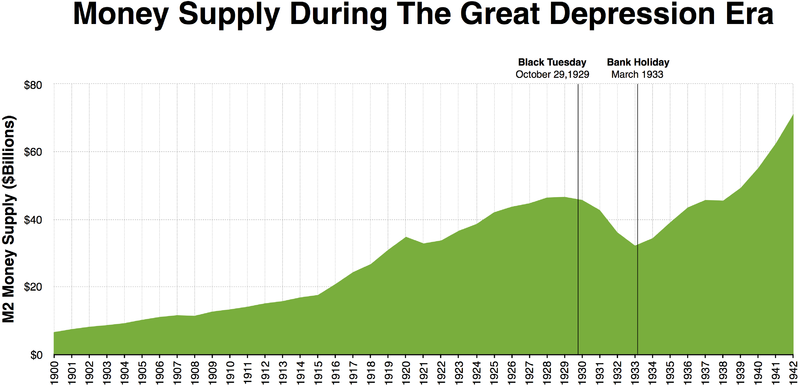

One of the most thorough and meticulously documented accounts of the Fed’s inflationary actions prior to 1929 is America’s Great Depression by the late Murray Rothbard. Using a broad measure that includes currency, demand and time deposits, and other ingredients, Rothbard estimated that the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply by more than 60 percent from mid-1921 to mid-1929. The flood of easy money drove interest rates down, pushed the stock market to dizzy heights, and gave birth to the “Roaring Twenties.”

By early 1929, the Federal Reserve was taking the punch away from the party. It choked off the money supply, raised interest rates, and for the next three years presided over a money supply that shrank by 30 percent. This deflation following the inflation wrenched the economy from tremendous boom to colossal bust.

The “smart” money — the Bernard Baruchs and the Joseph Kennedys who watched things like money supply — saw that the party was coming to an end before most other Americans did. Baruch actually began selling stocks and buying bonds and gold as early as 1928; Kennedy did likewise, commenting, “only a fool holds out for the top dollar.”

Phase 2, Hoover’s interventions and the disaster of Smoot-Hawley:

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot in April 1929, shortly before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives.

Library of Congress photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Unemployment in 1930 averaged a mildly recessionary 8.9 percent, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. It shot up rapidly until peaking out at more than 25 percent in 1933. Until March 1933, these were the years of President Herbert Hoover — the man that anti-capitalists depict as a champion of noninterventionist, laissez-faire economics.

Did Hoover really subscribe to a “hands off the economy,” free-market philosophy? His opponent in the 1932 election, Franklin Roosevelt, didn’t think so. During the campaign, Roosevelt blasted Hoover for spending and taxing too much, boosting the national debt, choking off trade, and putting millions of people on the dole. He accused the president of “reckless and extravagant” spending, of thinking “that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible,” and of presiding over “the greatest spending administration in peacetime in all of history.” Roosevelt’s running mate, John Nance Garner, charged that Hoover was “leading the country down the path of socialism.” Contrary to the modern myth about Hoover, Roosevelt and Garner were absolutely right.

The crowning folly of the Hoover administration was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed in June 1930. It came on top of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which had already put American agriculture in a tailspin during the preceding decade. The most protectionist legislation in U.S. history, Smoot-Hawley virtually closed the borders to foreign goods and ignited a vicious international trade war. Professor Barry Poulson notes that not only were 887 tariffs sharply increased, but the act broadened the list of dutiable commodities to 3,218 items as well.

Officials in the administration and in Congress believed that raising trade barriers would force Americans to buy more goods made at home, which would solve the nagging unemployment problem. They ignored an important principle of international commerce: trade is ultimately a two-way street; if foreigners cannot sell their goods here, then they cannot earn the dollars they need to buy here.

Phase 3, FDR and the New Deal:

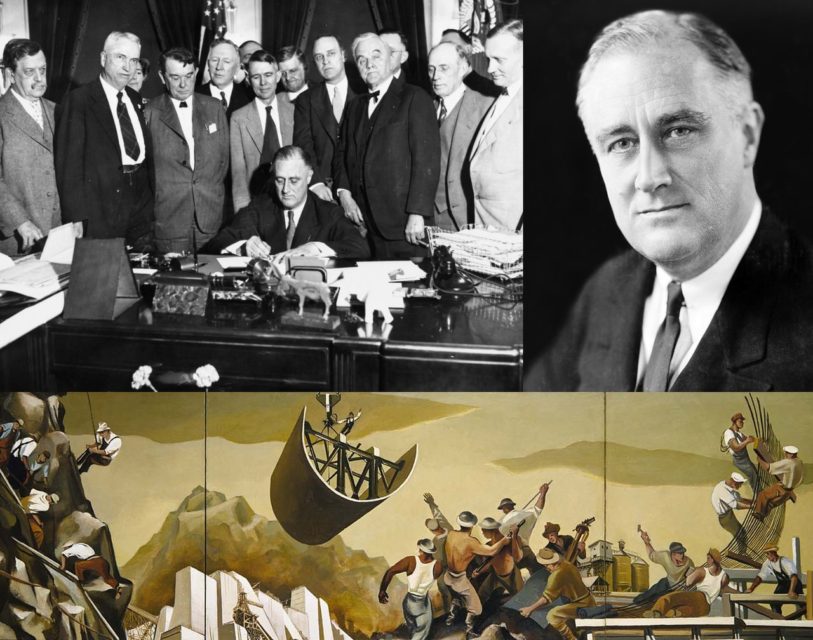

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election in a landslide, collecting 472 electoral votes to just 59 for the incumbent Herbert Hoover. The platform of the Democratic Party whose ticket Roosevelt headed declared, “We believe that a party platform is a covenant with the people to be faithfully kept by the party entrusted with power.” It called for a 25 percent reduction in federal spending, a balanced federal budget, a sound gold currency “to be preserved at all hazards,” the removal of government from areas that belonged more appropriately to private enterprise, and an end to the “extravagance” of Hoover’s farm programs. This is what candidate Roosevelt promised, but it bears no resemblance to what President Roosevelt actually delivered.

In the first year of the New Deal, Roosevelt proposed spending $10 billion while revenues were only $3 billion. Between 1933 and 1936, government expenditures rose by more than 83 percent. Federal debt skyrocketed by 73 percent.

[…] in 1935 the Works Progress Administration came along. It is known today as the very government program that gave rise to the new term, “boondoggle,” because it “produced” a lot more than the 77,000 bridges and 116,000 buildings to which its advocates loved to point as evidence of its efficacy. The stupefying roster of wasteful spending generated by these jobs programs represented a diversion of valuable resources to politically motivated and economically counterproductive purposes.

The American economy was soon relieved of the burden of some of the New Deal’s excesses when the Supreme Court outlawed the NRA in 1935 and the AAA in 1936, earning Roosevelt’s eternal wrath and derision. Recognizing much of what Roosevelt did as unconstitutional, the “nine old men” of the Court also threw out other, more minor acts and programs which hindered recovery.

Phase 4, the Wagner Act:

The stage was set for the 1937–38 collapse with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 — better known as the Wagner Act and organized labor’s “Magna Carta.” […] Armed with these sweeping new powers, labor unions went on a militant organizing frenzy. Threats, boycotts, strikes, seizures of plants, and widespread violence pushed productivity down sharply and unemployment up dramatically. Membership in the nation’s labor unions soared; by 1941 there were two and a half times as many Americans in unions as in 1935.

[…]

Higgs draws a close connection between the level of private investment and the course of the American economy in the 1930s. The relentless assaults of the Roosevelt administration — in both word and deed — against business, property, and free enterprise guaranteed that the capital needed to jumpstart the economy was either taxed away or forced into hiding. When Roosevelt took America to war in 1941, he eased up on his antibusiness agenda, but a great deal of the nation’s capital was diverted into the war effort instead of into plant expansion or consumer goods. Not until both Roosevelt and the war were gone did investors feel confident enough to “set in motion the postwar investment boom that powered the economy’s return to sustained prosperity.”

.