Business Insider

Published 19 Jan 2019The green paste you’ve been eating with your sushi isn’t really wasabi. If you check the ingredients on the packet, you might see a mixture of sweetener, horseradish and perhaps a small percentage of the real thing. Real wasabi is hard to come across and it can cost $250 per kilo. So what actually is wasabi, and why is it so expensive?

For more from The Wasabi Company, go to: https://www.thewasabicompany.co.uk/

——————————————————

#Wasabi #Expensive #BusinessInsider

Business Insider tells you all you need to know about business, finance, tech, retail, and more.

BI on Instagram: https://read.bi/2Q2D29T

BI on Twitter: https://read.bi/2xCnzGF

December 15, 2021

Why Real Wasabi Is So Expensive | So Expensive

November 16, 2021

Pineapple: the King of Fruits

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 15 Nov 2021Pineapples are so culturally significant that pineapples adorn the tops of cathedrals, and serve as the domicile of one of the world’s most popular cartoon characters. An estimated 300 billion pineapples are farmed each year, and a 2021 YouGov poll lists pineapples as the sixth most favorite fruit, ahead of all varieties of apples and oranges.

This is original content based on research by The History Guy. Images in the Public Domain are carefully selected and provide illustration. As very few images of the actual event are available in the Public Domain, images of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

You can purchase the bow tie worn in this episode at The Tie Bar:

https://www.thetiebar.com/?utm_campai…All events are portrayed in historical context and for educational purposes. No images or content are primarily intended to shock and disgust. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Non censuram.

Find The History Guy at:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

Please send suggestions for future episodes: Suggestions@TheHistoryGuy.netThe History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

https://teespring.com/stores/the-hist…Script by THG

#history #thehistoryguy #Pineapple

August 17, 2021

Early American Whiskey

Townsends

Published 3 Apr 2017Today Brian Cushing from Historic Locust Grove takes us on a tour of their new distillery and its history. #townsendswhiskey

Locust Grove Website ▶▶ http://locustgrove.org/ ▶

Help support the channel with Patreon ▶ https://www.patreon.com/townsend ▶▶

Twitter ▶ @Jas_Townsend

Instagram ▶ townsends_official

July 22, 2021

Bourbon, almost an accidental hit

At TownHall, Salena Zito discusses the way Bourbon became a popular modern beverage from a none-too-promising eighteenth century beginning:

“Bourbon Bottles” by larryjh1234 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

About 250 years ago, farmers looking for a way to make their surplus corn crop profitable decided to distill it. Today, that leftover grain has become a billion-dollar industry and a symbol of the Bluegrass State’s identity, economy and culture.

“How bourbon came about is (what) … the American spirit looks like: business, independence, freedom, a little bit of luck and a lot of perseverance,” said Justin Thompson.

Thompson and his colleague Justin Sloan are the proprietors of The House of Bourbon, the world’s largest bourbon store, located on West Main Street in Lexington right across from Mary Todd Lincoln’s childhood home.

And right now, business is booming.

Thompson and Sloan started collecting rare and vintage bottles of bourbon 20 years ago, when the drink was out of favor. Then, four years ago, the state passed a law allowing the resale of distilled spirits and the duo opened their store, selling not just their stockpile but the history of the drink itself.

Bourbon is concocted from a strict formula. “By law it has to be made with a minimum of 51% corn, aged in charred new oak barrels and stored at no more than 125 proof and bottled at no less than 80 proof,” Thompson said.

But its sweet, rich flavor was actually born out of happenstance. In the early days, the best market for bourbon was on the East Coast, so farmers had to ship their barrels down the Mississippi to Louisiana then around Florida and up the coast. The trip took months but also allowed the whiskey to age beautifully.

“When merchants along the East Coast started marveling about this red whiskey with its unique flavor, that marked the beginning of the bourbon industry,” said Thompson.

In 1964, Congress deemed bourbon the nation’s native spirit, and there’s nothing more American than enjoying a sip of the brown stuff in a classic cocktail like a mint julep or an Old-Fashioned on the Fourth of July weekend.

July 16, 2021

The lure of London and agricultural specialization in post-Black Death England

In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the “push” and “pull” theories to account for the vast growth of London and how that urban growth strongly encouraged specialization in English agriculture to feed the great city:

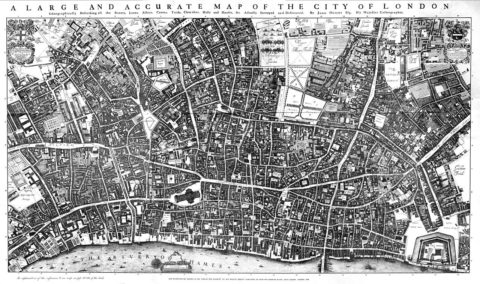

The 1677 original of this map is 8 feet 5 inches by 4 feet 7 inches, in 20 sheets. In 1894 the British Museum granted permission to the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society to make a reduced copy, of which the original of this scan is a copy. The L&M Society copy apparently did not match the dissected sheets perfectly, and the misjoins can be seen in places in this reproduction.

Scanned copy of reproduction in Maps of Old London (1908) of Ogilby & Morgan’s Map of London.

Something significant happened to the English countryside in the century before 1650. Although England’s population merely recovered to its pre-Black Death high of about 5 million, the economy was transformed. Having once been an overwhelmingly agrarian society, by 1650 a small but unprecedented proportion of the population now lived in cities, and less than half of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The country had de-agrarianised, and most remarkably of all, its food was still grown at home.

[…]

One possibly explanation is that there was some special change in England’s agricultural technology that increased its productivity, requiring fewer and fewer people, and possibly even driving them off the land, so that they were forced to find alternative employment. This thesis comes in various forms, many of which I’m still coming to grips with, but broadly speaking it implies a “push” from the fields, and into industry and the cities. Desperate, and unable to demand high wages, these cheaper workers should have stimulated industry’s growth.

The alternative, however, is that there was nothing very special or innovative about English agriculture, and that instead there was an even larger increase in the demand for workers in industry and services. The thesis implies a “pull” into industry and the cities, causing people to abandon agriculture for more profitable pursuits, and thereby making England’s agriculture de facto more productive — something that may or may not have actually been accompanied by any changes to agricultural technology, depending on how much slack there was in how the labourers or land had been employed.

The push thesis implies agricultural productivity was an original cause of England’s structural transformation; the pull thesis that it was a result. The evidence, I think, is in favour of a pull — specifically one caused by the dramatic growth of London’s trade.

Even though the population eventually recovered from the massive impact of the Black Death, not all of the land that was under plough was returned to active farming and a much greater diversity of uses for rural land emerged, including more pastures for grazing livestock, and small cash crops to be sold into the cities (especially into London).

With the dramatic growth of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the more intensive methods came to be in much higher demand. Indeed, the extraordinary pull of the city’s growth resulted in English agriculture becoming increasingly specialised. Not only were there millions of acres of pasture still left that could be returned to the plough, but despite the relative fall in the prices of livestock, some areas actually became even more devoted to pasture. Many of the villages that had been abandoned after the Black Death were, even by the 1870s, over half a millennium later, still not being farmed. With wealthy Londoners demanding more varied diets, with meat and dairy, the various regions of England discovered their comparative advantages rather than all shifting to grain. There was thus extra room for agriculture to become more productive simply by devoting the best land for pasture to pasture, and the best soils for arable to arable, then trading the produce with one another, rather than have each area try to be self-sufficient. It’s something we also see in the decline of grains like rye, especially near London, to be replaced by wheat — the switching of a crop best-suited to local subsistence, to one that could be sold elsewhere and in bulk for cash.

In general, the south and east of England became increasingly arable, while the north-west concentrated on pasture. Yet there were also exceptions to be made for London’s particular wants. Thus, county Durham converted more land to arable to feed the miners of Newcastle coal, used to heat London’s homes; and the county of Middlesex, now largely disappeared under London’s own expansion, specialised in pasture for horses, rather than feeding people, so as to feed the city’s main sources of transportation. As the writer Daniel Defoe put it in the 1720s, “this whole Kingdom, as well the people, as the land, and even the sea, in every part of it, are employed to furnish something, and I may add, the best of everything, to supply the city of London with provisions.”

July 2, 2021

Britain’s “agricultural revolution”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes wonders about the almost-forgotten revolution that pre-dated the much better known Industrial Revolution:

Illustration of a seed drill from Horse-hoeing husbandry, 4th edition by Jethro Tull, 1762 (original work 1731).

Wikimedia Commons.

Whatever happened to “the Agricultural Revolution” of seventeenth and eighteenth-century Britain? In recent years I’ve hardly seen the term used at all, and the last major book on the subject was seemingly published twenty-five years ago. It has become almost totally eclipsed by its more famous sibling “the Industrial Revolution”, with its vivid associations of cotton, coal, and exponential hockey-stick graphs.

Yet for all that popularity, nearly every book investigating the causes of modern economic growth complains about the use of The Industrial Revolution. Even one of the pioneers of economic history, T. S. Ashton, who actually wrote the book The Industrial Revolution, complained on the very second page about the term’s inaccuracy. Much like “Holy Roman Empire”, there’s an error in every word. It involved too many series of changes to really be a The, was about so much more than just industry, and was too gradual a process to properly call a revolution. Yet Ashton had to concede that the term had “become so firmly embedded in common speech that it would be pedantic to offer a substitute.” And this was in 1948. In the intervening three quarters of a century, the term has become all the more difficult to dislodge.

I am, like everyone else, guilty of perpetuating the term Industrial Revolution. It’s a useful shorthand for people to at least get a rough idea of what I’m talking about, for me to then refine. Best to start with what people know, or at least what they think they know, and go from there. You may think of the Industrial Revolution as being about cotton, coal, and steam, but the period also saw major developments in every other industry, from agriculture to watch-making, and everything in-between. And so on. My preferred terms, like “acceleration of innovation”, always require at least a paragraph or two of explanation first.

With the term Agricultural Revolution, however, there’s just no need to reference it. Nobody really talks about it, or has anything more than a very vague conception of what it may mean. At best, people recall a few things from decades-old textbooks: names like “Turnip” Townshend or Jethro Tull, and perhaps a smattering of jargon like selective breeding, crop rotation, or enclosures. Even these are widely misunderstood. See last week’s post, for patrons, on how we get almost everything about the enclosure movement wrong. As for the Agricultural Revolution’s timing, who knows? When, over the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and maybe even nineteenth centuries is it supposed to have occurred? With the Industrial Revolution, there’s at least a “classic” period of 1760-1830, with a few decades of leeway. That is of course up for debate, and I’m especially keen on pushing it back much earlier, but it’s at least a half-decent starting point. With the Agricultural Revolution, there’s just no baseline at all. The experts themselves can’t agree.

For all that the term Agricultural Revolution has lost its salience, however, early modern changes to the productivity of agriculture were perhaps the most important of all. The ability to support a much larger population is itself a major economic achievement. For all that we obsess over historical measures of GDP per person, we often forget the much earlier and extraordinary increase in just the sheer number of people. In the early seventeenth century England’s population not only recovered to its pre-Black Death peak of about 5 million, but then from 1700 onwards it began to exceed it. By 1800, after just another century, the population of Britain had doubled to 10 million. And this in a period throughout which the country was a net exporter of grain.

May 6, 2021

March 7, 2021

Seeking the origin of Vitis vinifera, the grape vine used for most wine

A mailing from Kacaba Vineyards included a link to this Wine Folly article by Madeline Puckette discussing the origins of the grapes we use for the vast majority of table wines:

Where did wine come from? It wasn’t France. Nor was it Italy. Vitis vinifera, also known as “the common wine grape,” has an unexpected homeland! Let’s dive into the origin of wine.

Current evidence suggests wine grapes originated in West Asia.

Map by Wine Folly based on Google Earth imagery.Where is The True Origin of Wine?

Current evidence suggests that wine originated in West Asia including Caucasus Mountains, Zagros Mountains, Euphrates River Valley, and Southeastern Anatolia. This area spans a large area that includes the modern day nations of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, northern Iran, and eastern Turkey.

Ancient wine production evidence dates between 6,000 BC and 4,000 BC, and includes an ancient winery site in Armenia, grape residue found in clay jars in Georgia, and signs of grape domestication in eastern Turkey. We still haven’t pin-pointed the specific origin of wine, but we think we know who made it!

The Shulaveri-Shomu people (or “Shulaveri-Shomutepe Culture”) are thought to be the earliest people making wine in this area. This was during the Stone Age (neolithic period) when people used obsidian for tools, raised cattle and pigs, and most importantly, grew grapes.

February 5, 2021

QotD: Misunderstanding the threat/promise of robotics and AI

So, start with the very basics. Human desires and needs are unlimited – that’s an assumption but a reasonable one. There’re some number of people on the planet. This provides us with a lot of human labour but not an unlimited amount. Thus labour is a scarce or economic resource – and we’ve not enough of it to sate all human desires and wants.

OK, so, now we use machines to do some jobs that were previously done by humans. Imagine that this new technology actually required more human labour – that it created new jobs in greater volume than those it destroys. Say, the tractor and combine harvester industry needs more people in it than we used to use to cut the crops by hand. We’ve just made ourselves poorer. We used to have some amount of grain through the labour of some number of people. We’ve now got that grain but by using the labour of more people. We’ve used more of our scarce resource and we’re now poorer by the loss of what they used to make when not hand cutting grain but now no longer are by making tractors.

What makes us richer is if the tractor industry has record production statistics while using less labour than the hammer and sickle. That means that some human labour is now free to go off and try to sate a human desire or want for something other than grain. Ballet dancing for example. We’re now richer – tractors and combine harvesters have made us richer – by whatever value we put on more ballet dancing.

The entire point of any form of automation is to destroy jobs so as to free up that labour to do something else. The new technology doesn’t create jobs, it allows other jobs to be done.

The only point at which this fails is if human needs and desires aren’t unlimited. Which means that we might be able to provide everything that everyone wants without us all working. Which doesn’t really sound like much of a problem really.

Tim Worstall, “As Usual, World Economic Forum Gets Robots And AI Wrong Over Jobs”, Continental Telegraph, 2018-09-18.

January 22, 2021

QotD: The enclosure movement, in historical fact and in Marxist imagining

Consider, for example, that the tenfold increase [in the population of London] was in the period before the expropriative parliamentary enclosures of Marxist legend, when state fiat was used to deny smaller farmers their ancient, customary rights to use the land near their villages. While the very first of these enclosure acts appeared as early as 1604, parliamentary enclosure only really got going from the mid-eighteenth century. Instead, for the period in question, enclosure happened in a piecemeal way, with the open fields gradually dissolving as farmers exchanged or sold their tiny strips of land, over time amalgamating them into larger, privately controlled plots. With ownership concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, it became relatively easy to gain the unanimity needed to suspend common rights. The process played out in myriad ways all over the country, sometimes with amicable agreement and voluntary exchange, sometimes with ruthless monopolising of the land, with the already-large owners systematically buying out their neighbours. In some cases it involved the consolidation of existing arable land, in others it meant the conversion of forest, heath, marsh, or fen — the traditional “wastes”, to which the poorer villagers might have had various customary rights to gather firewood for fuel, or to graze their cattle, or to hunt for small game — into land that could be used for farming or pasture.

How this process played out all depended on extremely specific, local conditions. But on the whole it was slow — piecemeal enclosure had been happening to varying degrees since at least the fourteenth century. It’s hard to see how such a sporadic and piecemeal process could have led to such consistently and increasingly massive numbers flocking specifically to London. Indeed, the fact that they singled out London as their target suggests that this narrative might have it back-to-front. Some economic historians argue that it was the prospect of higher wages in the ever-growing metropolis that induced farmers to leave the countryside in the first place, selling up or abandoning their plots to those they left behind. Rather than enclosure pushing peasants off the land and into the city, London’s specific pull may instead have thus created the vacuum that allowed the remaining farmers to bring about enclosure. Otherwise, why didn’t the peasants simply flock to any old urban centre? The second-tier cities like Norwich or Bristol or Exeter or Coventry or York would all have been far less dangerous.

Anton Howes, “London the Great”, Age of Invention, 2020-10-20.

November 10, 2020

The amazing mental gymnastics that lead to the US Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Wickard v. Filburn in 1942

Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan explain how a farmer growing wheat on his own land to feed his own cattle somehow transmogrified into an interstate commerce activity that could be regulated by the federal government:

Panorama of the west facade of United States Supreme Court Building at dusk in Washington, D.C., 10 October, 2011.

Photo by Joe Ravi via Wikimedia Commons.

… who ended up being tasked with deciding what Article One, Section Eight actually meant? Herein lies the wrinkle that enables all manner of constitutional mischief in the United States. The institution that ended up deciding what the federal government is empowered to do is itself a branch of the federal government. And it should come as no surprise that when push comes to shove, the Supreme Court routinely finds in favor of empowering the federal government.

This sort of mischief flowered fully in the decade following ratification of the 21st Amendment. In 1942, the Supreme Court decided a case, Wickard v. Filburn, in which farmer Roscoe Filburn ran afoul of a federal law that limited how much wheat he was allowed to grow.

A careful reader might, and should, ask where the federal government’s right to legislate the wheat market is to be found — because the word “wheat” is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. Be that as it may, the federal government’s aim was clear enough. It was to keep the price of wheat high enough for farmers to remain profitable. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 put an upper limit on how much wheat farmers were allowed to grow, which would serve to keep prices high by limiting supply.

Roscoe Filburn had grown 12 more acres of wheat than the law allowed. But not only did he not sell the excess wheat outside of his home state, but he also didn’t sell it at all. He used the wheat from those 12 acres to feed his cattle. Filburn was very clearly not engaging in commerce, let alone interstate commerce, yet the Supreme Court found (unanimously) that because Congress had the authority to regulate interstate commerce, Congress also had the authority to prohibit Filburn from growing those 12 acres of wheat for his own use. The Supreme Court’s “reasoning”?

Had Filburn not fed his cattle that excess wheat, he would have been forced to purchase wheat on the open market. And even if he purchased wheat that was grown within his home state, doing so would have made less wheat available within his home state for other wheat buyers. Consequently, some wheat buyers within his home state would then have had to buy wheat from outside the state. Therefore, Filburn’s non-commercial activity was, according to the Supreme Court, interstate commerce.

The mental gymnastics that went into this ruling made just about any activity interstate commerce by definition. Since Wickard, any time Congress has wanted to exercise power not authorized by the Constitution, lawmakers have simply had to make an argument that links whatever they want to accomplish to interstate commerce. Why? Because they know they can get away with it.

November 3, 2020

QotD: Water pricing

Near all freshwater availability problems come from the fact that farmers get it cheap or for free, diverting it from much more valuable uses like keeping people alive if they drink it. This is true in California – we’ve actually cases of farmers using $400 of water to grow $100 of alfalfa – as it is in Pakistan. There are cases of people growing water hungry crops in near drought areas just because they get that water too cheaply.

[…]

Gaining revenue with which to build dams is useful, it most certainly is. But that’s not the only function of pricing. The cash to increase supply, great, but the very fact of charging will reduce demand. And we should be charging what it costs to produce the water too. So charges should cover 100% of the costs of the dams, not just 25%.

It’s entirely possible that charging that full cost will mean that no farmers want the water. OK, then we shouldn’t build the dam, should we? For if the value of the water – measured by what people will pay – is less than the cost of its provision, then that’s value destroying, providing the water. The dam makes us all poorer, therefore we shouldn’t build it.

The point here being – and it’s an important one – that prices affect both supply and demand. They’re what brings them into balance even. So, yes, charge for water, but not just so that we can pay to increase supply, also so that we, merely by charging, reduce demand.

Tim Worstall, “Pakistan’s Chief Justice Almost Right – Charge For Water, Not For Dams, But To Charge For Water”, Continental Telegraph, 2017-07-17.

September 18, 2020

From innovation to absolutism — English inventors and the Divine Right of Kings

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at how innovations during the late Tudor and Stuart eras sometimes bolstered the monarchy in its financial battles with Parliament (which, in turn, eventually led to actual battles during the English Civil War):

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

The various schemes that innovators proposed — from finding a northeast passage to China, to starting a brass industry, to colonising Virginia, or boosting the fish industry by importing Dutch salt-making methods — all promised to benefit the public. They were to support the “common weal”, or commonwealth. And to a certain extent, many projects did. The historian Joan Thirsk did much pioneering work in the 1970s to trace the impact of various technological or commercial projects, revealing that even something as mundane as growing woad, for its blue dye, could have a dramatic impact on local economies. With woad, the income of an ordinary farm labouring household might be almost doubled, for four months in the year, by employing women and children. In the late 1580s, the 5,000 or so acres converted to woad-growing in the south of England likely employed about 20,000 people. That may seem small today, but at a time when the population of a typical market town was a paltry 800 people, even a few hundred acres of woad being cultivated here or there might draw in workers from across the whole region. In the mid-sixteenth century, even the entire population of London had only been about 50-70,000. As Thirsk discovered, innovative projectors also sometimes fulfilled their other public-spirited promises, for example by creating domestic substitutes for costly imported goods, or securing the supplies of strategic resources.

But the ideal of benefiting the commonwealth could also, all too frequently, be elided with serving the interests of the Crown. Projectors might promise the monarch a direct share of an invention’s profits, or that a stimulated industry would result in higher income from tariffs or excise taxes. Increasingly, they proposed schemes that were almost entirely focused on maximising state revenue, with little evidence of new technology. They identified “abuses” in certain industries — at this remove, it’s difficult to tell if these justifications were real — and asked for monopolies over them in order to “regulate” them, then making money by selling licences. Last week I mentioned patents over alehouses, and on playing cards. They also offered to increase the income from the Crown’s property, for example by finding so-called “concealed lands” — lands that had been seized during the Reformation, but which through local resistance or corruption had ostensibly not been paying their proper rents. The projectors would take their share of the money they identified as “missing”. And they proposed enforcing laws, especially if the punishments involved levying fines or confiscating property. The projectors offered to find the lawbreakers and prosecute them, after which they’d take their share of the financial punishments.

Projectors thus came to present themselves as state revenue-raisers and enforcers, circumventing all of the traditional constraints on the monarch’s money and power. They provided an alternative to Parliaments, as well as to city corporations and guilds, in raising money and propagating their rule. Taking it a step further, projectors offered the tantalising possibility that kings like James I and Charles I might rule through proclamation and patents alone, without having to answer to anybody. They thus experimented with absolutism for much of 1610-40, only occasionally being forced to call Parliament for as briefly as possible when the pressing financial demands of war intervened.

In the process, with the growing multitude of projects — a few bringing technological advancement, but many merely lining the pockets of courtier and king — the designation “projector” became mud. It was as if, today, the Queen were to use her prerogative to grant a few of her courtiers monopolies on collecting all traffic fines, or litter penalties, to be rewarded solely on commission. Or if she were to award an unscrupulous private company the right to award all alcohol-selling licences (perhaps on the basis that underage drinking was becoming common). The country would soon be awash with hidden speed cameras and incognito litter wardens, and the price of alcohol would go through the roof. The people responsible would not be popular. A recent book by economic historian Koji Yamamoto meticulously charts the changing public perceptions of projects, describing the ways in which innovators then struggled, for decades, to regain the public’s trust.

August 3, 2020

Romanticizing the past

Sarah Hoyt points out that the past really is a foreign country and they do things very differently there … and for good reasons:

An image of coal pits in the Black Country from Griffiths’ Guide to the iron trade of Great Britain, 1873.

Image digitized by the Robarts Library of the University of Toronto via Wikimedia Commons.

So, quickly: The industrial revolution was not a disaster to your average peasant. It was a disaster for landowners.

Yes, yes, the conditions in the factories were terrible. By our standards. The lifespan was very short. By our standards. The anomie of the big cities, yadda yadda. When compared to what? Small villages? Ask those of us raised in them. Yes, there was child labor. As compared to what at that time? Other than the life of the upper classes?

Look, we don’t have to guess about this stuff. In India, in China, in other places that came to the industrial revolution very late, we’ve seen peasants leave the land where their ancestors had labored, to flock to the big cities, to take work we find horrible and exploitative at wages we find ridiculous.

And even if China has added “labor camp” and prisoner wrinkles to it, note that’s because China is a shitty communist country, not because the migration wasn’t there before. Also the labor camp aspects, as much as one can tell (and it’s hard to tell, due to the raging insanity of the regime) seem to have grown as the people grew more prosperous, as a result of the industrial revolution and thereby demanded higher wages, which positioned China more poorly as the “factory of the world.”

In fact, idealizing “living off the land” has been in place since at least the Roman empire, and probably before. It’s also been MISERABLE at least since then and probably before.

Because pre-industrial revolution farming sucked. It sucked horribly. And it kept you on the edge of subsistence. It double sucked when you were subjected to a Lord. Look, systems of serfdom, etc. didn’t come about because living in a Lord’s domain was so great, and everyone wove wreaths and danced around maypoles all the time, okay?

The bucolic paradise of a farmer’s life was mostly a creation of city dwellers, often noblemen, who saw it from the outside.

There are estimations that most people had trouble rearing even one child, and most of one generation’s peasants were people fallen from higher status. I don’t know. That might be exaggerated. Or it might not.

Even during the industrial revolution, it was normal for ladies bountiful to take baskets of food to tenant farmers because … they couldn’t make it on their own.

And btw, the more the industrial revolution pulled people to the cities, the more the Lords and “elites” talked about how great the countryside was and how terrible the factories/cities/new way of living were.

A lot of artists and pseudo bohemians jumped in on this bandwagon and so did Marx, who was both a pseudo bohemian, by birth “elite” (Well, his family had a virtual slave attached to him. He impregnated her too, as was his privilege), and by self-flattery intellectual.

Therefore the factories were the worst thing ever, the men who owned them, aka capitalists were terrible, terrible people — mostly because Marx wasn’t one, and probably because they laughed at him — and the proletariat they exploited horribly would rise up and —

All bullshit of course. Later on his fiction needed retconning by Anthony Gramsci who, having the sense to realize the “workers” weren’t rising up, just getting wealthier and escaping the clutches of the “elites” more made the “proletariat” a sort of “world proletariat” centered on poorer/more dysfunctional countries. This had the advantage of making the exploited masses always be elsewhere (or the supposed exploiters) and therefore made it easier to pitch group against group to the eternal profit of rather corrupt “elites.” Mostly political classes which are descended from “the best people.”

July 28, 2020

How Matt Ridley stopped being an “Enviro-Pessimist”

It was human ingenuity that did it for him:

Spiti Valley in the Great Himalayan National Park. (The little blue speck in the middle of the photo is a truck, for scale.)

Photo by Sudhanshu Gupta via Wikimedia Commons.

If you had asked me in 1980 to predict what would happen to that bird and its forest ecosystem, I would have been very pessimistic. I could see the effect on the forests of growing human populations, with their guns and flocks of sheep. More generally, I was marinated in gloom by almost everything I read about the environment. The human population explosion was unstoppable; billions were going to die of famine; malaria and other diseases were going to increase; oil, gas, and metals would soon run out, forcing us to return to burning wood; most forests would then be felled; deserts were expanding; half of all species were heading for extinction; the great whales would soon be gone from the oil-stained oceans; sprawling cities and modern farms were going to swallow up the last wild places; and pollution of the air, rivers, sea, and earth was beginning to threaten a planetary ecological breakdown. I don’t remember reading anything remotely optimistic about the future of the planet.

Today, the valleys we worked in are part of the Great Himalayan National Park, a protected area that gained prestigious World Heritage status in 2014. The logo of the park is an image of the western tragopan, a bird you can now go on a trekking holiday specifically to watch. It has not gone extinct, and although it is still rare and hard to spot, the latest population estimate is considerably higher than anybody expected back then. The area remains mostly a wilderness accessible largely on foot, and the forests and alpine meadows have partly recovered from too much grazing, hunting, and logging. Ecotourism is flourishing.

This is just one small example of things going right in the environment. Let me give some bigger ones. Far from starving, the seven billion people who now inhabit the planet are far better fed than the four billion of 1980. Famine has pretty much gone extinct in recent decades. In the 1960s, about two million people died of famine; in the decade that just ended, tens of thousands died — and those were in countries run by callous tyrants. Paul Ehrlich, the ecologist and best-selling author who declared in 1968 that “[t]he battle to feed all of humanity is over” and forecast that “hundreds of millions of people will starve to death” — and was given a genius award for it — proved to be very badly wrong.

Remarkably, this feeding of seven billion people has happened without taking much new land under the plow and the cow. Instead, in many places farmland has reverted to wilderness. In 2009, Jesse Ausubel of Rockefeller University calculated that thanks to more farmers getting access to better fertilizers, pesticides, and biotechnology, the area of land needed to produce a given quantity of food — averaged for all crops — was 65 percent less than in 1961. As a result, an area the size of India will be freed up by mid-century. That is an enormous boost for wildlife. National parks and other protected areas have expanded steadily as well.

Nor have these agricultural improvements on the whole brought new problems of pollution in their wake. Quite the reverse. The replacement of pesticides like DDT with much less harmful ones that do not persist in the environment and accumulate up the food chain, in addition to advances in biotechnology, has allowed wildlife to begin to recover. In the part of northern England where I live, otters have returned to the rivers, and hawks, kites, ospreys, and falcons to the skies, largely thanks to the elimination of organochlorine pesticides. Where genetically modified crops are grown — not in the European Union — there has been a 37 percent reduction in the use of insecticides, as shown by a recent study done at Gottingen University.

One of the extraordinary features of the past 40 years has been the reappearance of wildlife that was once seemingly headed for extinction. Bald eagles have bounced back so spectacularly that they have been taken off the endangered list. Deer and beavers have spread into the suburbs of cities, followed by coyotes, bears, and even wolves. The wolf has now recolonized much of Germany, France, and even parts of the heavily populated Netherlands. Estuaries have been cleaned up so that fish and birds have recolonized rivers like the Thames.