Feral Historian

Published 15 Nov 2024The first book in S.M. Stirling’s Emberverse series, Dies The Fire yanks modern technology out of the world and sets the stage for a multi-faceted exploration of how distinct cultures emerge from small isolated groups and the profound effect individuals can have the societies that coalesce around them.

00:00 Intro

01:28 Founders

03:37 Desperation

04:51 Flawed Assumptions

07:05 Composites and Rhymes

(more…)

March 30, 2025

Dies the Fire and the Founder Effect

March 29, 2025

The Life of Plutarch

MoAn Inc.

Published 19 Sept 2024#AncientHistory #AncientGreece #Plutarch

Donate Here: https://www.ko-fi.com/moaninc

March 13, 2025

“Canadian liberalism has been regime ideology since at least Lester B. Pearson in 1963”

Fortissax on “Leaflibs & Puckstick Patriots”:

The past week has been very special because something happened in Canada. This something is not anything I could have anticipated, but I find myself not particularly surprised. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau propped up the husk of Jeff Douglas like an old Fisher King from some retelling of Arthurian legend. Jeff Douglas is famous for his appearance in the Molson Canadian beer commercial, released in the year 2000. This commercial was possibly the hardest-hitting, if not among the top hardest-hitting, propaganda pieces ever produced in service of regime ideology. That regime ideology is Canadian liberalism — a form of left-liberalism that emerged out of the Second World War, in direct contradiction to American right-liberalism.

Many American correspondents have asked me to explain why it seems like liberals are patriotic in Canada, while conservatives are not. The answer is simple: Canadian liberalism has been regime ideology since at least Lester B. Pearson in 1963, Pierre Trudeau’s predecessor, who laid the groundwork for a sinister, transformative cultural revolution — the likes of which I can only compare to the USSR or Communist China.

What occurred in this era was a complete and total restructuring of society — an absolutely Orwellian mind-wipe of Canadian identity, a retconning of Canadian history, culminating in the explicit purpose of erasing the historic Canadian nation. So successful was this cultural revolution that, for my entire 30 years of life, the narrative has been that Canada is an illegitimate, post-national state on stolen land. Paradoxically, the people are viciously patriotic toward the hollow state, whose newfound identity obsesses over its own dissolution, its symbols and icons mostly channeled into corporate brands and products, like Canadian Tire, fast food chains like Tim Hortons, and the timeless bread and circuses of hockey.

Canada was transformed into an international economic zone of individuals with relatively maximal allotments for personal fulfilment — including the most licentious, disgusting, and degenerate, as long as it remains acceptable within the Overton window of the time.

A cornerstone of this identity is precisely outdoing the U.S. in how liberal it can be — true to the end goal of transnational liberals like Francis Fukuyama in The End of History and the Last Man. In this 63-year era, there are two archetypes of the average man or woman. These archetypes manifest as more moderate, more common versions of the populist American wannabe or the neurotic DEI cultist I discussed in my other article. These are what I’ve coined “leaflibs” and “puckstick patriots”. They represent the centre-left liberal and centre-right liberal majority of Canada.

There is often overlap between the two, but what they have in common is an extreme ignorance of Canadian and world history and national identity. Both regularly partake in the communion of the left-liberal civic religion but do so in different ways. They are also united in that the vast majority of information they obtain about local, regional, and national politics comes from legacy media outlets like the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (state-owned, publicly funded broadcaster), CTV, and Global News — old-school news outlets whose private owners and shareholders differ little in belief.

What the Canadian ruling classes have in common is that they are extremely insular and scarcely interact with the public. In many ways, Canada resembles European countries. Canadians were, for a long time, educated along stratified British class lines, and everyone knew their place. Canada’s national value is Order, not Liberty, and traditionally, society functioned as a collective, organic whole in a proper communitarian model, where the social expectation of the enlightened and powerful elites was to tend to their responsibilities of responsible government.

Let’s discuss these two “normie” archetypes. International readers, especially Americans, may notice parallels with their own mainstream liberal and conservative, yet otherwise ill-informed, media-consuming relations.

March 10, 2025

QotD: The “Basic College Dude” of the 2020s

… though I have written probably 50,000 words on the Basic College Girl over the years, I have spent almost no time on her opposite number, hereby christened the Basic College Dude (BCD). Admittedly some part of this is structural: There just aren’t that many Persyns of Penis in college these days — nationwide, college enrollment is something like 65% female and climbing; I bet there are more than a few small colleges that, while technically coed, are almost exclusively female. Also, I taught mostly freshman-level History classes, and since I was one of the few dinosaurs who didn’t make attendance a part of the class grade, only the congenital rule-followers, i.e. chicks, showed up.

But mostly it’s just because none of them stick in my memory. The #1 characteristic of the Basic College Dude is that even if he’s there, he’s not there. He’s checked out — mentally, emotionally, spiritually (if that even means anything anymore). Unlike the girls, all of whom seem to be in 72 different clubs and organizations (and list them all on their email auto-signatures, such that by junior year, their honorifics are longer than my entire resume), the guys don’t seem to do much of anything. How do they while away their hours? I assume with social media, like everyone, and with video games and blackout drinking …

… the latter of which I have seen, a lot, and if you’ll permit a brief digression, if you really want to know how fucked our society is, go to a student bar on a Friday night. I myself was a bit of a party animal in college, and like everyone I went over the line a few times, but college kid drinking these days is almost Soviet — they’re aiming to get knee-walking, gutter-puking, total-blackout shitfaced, and they set about it as grimly and efficiently as possible. The girls, too, with the added bonus that they’re all on Ambien and Klonopin and every other happy pill you’ve ever heard of, which makes for some interesting, by which I mean terrifying, behavior …

[…]

But mostly it’s because college dudes have had their libidos beaten out of them. […]

Not only does the BCD not know how to do this, as Nikolai says, he apparently doesn’t actually want to. Constant stimulation by blinking screens, shit diets, and a lifetime of indoctrination have reversed the sexual dilithium crystals. Heartiste used to go on about this, and while I’m no biochemist, either, I think his theory is sound: There’s so much environmental estrogen floating around that men develop the emotional equivalent of gynecomastia, while women turn butch. Throw nth wave feminism into the mix, and you’ve got women acting like the crudest, most obnoxious male stereotypes (they call this “being strong and empowered”), while the men mope and sigh to their diaries.

The end result is that the BCD walks around like he’s shellshocked. He does the bare minimum, hoping to just grind it out without any further affronts to his basic human dignity … but so mal-educated is he, that the phrase “basic human dignity” doesn’t even register with him.

Severian, “The Basic College Dude”, Founding Questions, 2021-10-05.

March 8, 2025

Kevin Zucker on “The Big Fat Surprise”

I just got the most recent free Wargame Design PDF from Operational Studies Group and found that Kevin Zucker, the head of the company and one of the best wargame designers ever, had indulged in a little bit of non-wargame writing to open this issue:

For decades, Teicholz tells us,

… we have been told that the best possible diet involves cutting back on fat, especially saturated fat, and that if we are not getting healthier or thinner it must be because we are not trying hard enough. But what if the low-fat diet is itself the problem? What if the creamy cheeses, the sizzling steaks are themselves the key to reversing the epidemics of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease? Misinformation about saturated fats took hold in the scientific community, but recent findings have overturned these beliefs. Nutrition science has gotten it wrong, through a combination of ego, bias, and premature consensus, allowing specious conclusions to become dietary dogma.1

We are conditioned to think that some specialist always knows better than we do. Despite the common wisdom, I always ate butter, not margarine, despite the “experts”, because I trusted my instincts.2 With experts influencing you to disregard your senses and what you already know, you can learn to believe the opposite of what is natural and true … “Boys and girls are the same”; “men and women are the same”. The French structuralists, who have somehow taken over academia, talk as if the whole world is merely a verbal construct, and whatever we speak becomes literally true if repeated enough.3

In the 1960’s and ’70’s, males joined the feminine on a quest for identity through music, love and drugs. I too was taken-in by the “men and women are the same” argument, and fancied myself a feminist. For me, that illusion was eventually shattered upon contact with reality. Today, instead of liberation, in many quarters the feminine principle is actively denied and suppressed; to prove a point, many women have short-circuited their feminine side, while masculinity is reviled as toxic. So now we have feminized men and masculine women, and neither side is happy. Seventy percent of divorces are initiated by women.

During the recent campaign, women’s anger was used to divide the sexes. A wife filed for divorce in November because her spouse voted for the wrong candidate. Supporters of the two sides cannot even be in the same house, much less discuss their differences rationally. After all, someone might get “triggered”, a brand-new coinage that promotes a fatal lack of reflection. The media have abandoned the fig leaf of nuance and balance and have hit their stride in stirring up fear and polarizing hatred.

The main tool of the demagogue is to stir up one group against another: divide and conquer. How does a society remove the influence of demagogues? History shows that once democracy is destroyed, it doesn’t just grow back. Undemocratic methods, such as censorship, brainwashing, propaganda, and the stifling of dissent, cannot “protect” democracy — just the opposite. A government is only an instrumentality of power, and it is only as democratic as its administrative cogwheels. Power is either administered democratically or it is usurped by a strong man, by the administrative state, or by oligarchs such as the World Economic Forum (who meet regularly in Davos, Switzerland). So that is the choice we face at the moment. Ten years ago, a study by professors Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page found America to be no longer a democracy, but a functional oligarchy. Aside from the eternal vices of greed and projection, we urgently need a strong repudiation of the folly of structuralism. This conversation should be taking place in academia, whose original purpose was to foster such discussions, but academia has now become the stronghold of “safe spaces” where open dialogue cannot be held.

The main reason for studying history, in my view, is to understand the present moment: Where are we, where did we come from, how did we get here, where are we going?4

Today, I am hopeful, for the first time since January 2009. In a chat with my good friend John Prados, I remarked, “Surely, like the proverbial stopped clock, by sheer accident, Trump might be correct about a few things”.

“No, Kevin, everything he says is a calculated lie,” reducing politics to a cartoonish level. We are, after all, the first generation raised on cartoons, where good and evil are simplistically segregated into representative types. Donald Trump has been cast as “Bluto”. The President has certainly brought grist for the mill by his tweet of 15 February, echoing Napoleon: “He who saves his country does not violate any law”.5 We might not have Trump in office today if his first campaign hadn’t been assisted by the Clinton machine in 2016. He was the candidate they wanted to run against, so they promoted his tweets and made a star out of him — just to help him in the primaries. Unfortunately, they created a monster.

It is obvious that the two candidates in the recent election are not the best our country has to offer. This reveals the absolute corruption of the political system. It has been obvious for some time that most of our institutions are vastly corrupt, with disastrous consequences for all of us. As a historian it is not my job to take sides or make predictions about the future. In my view, no one can predict the future: neither of the stock market, nor even tomorrow’s weather. A historian has to be concerned with facts, known, established and well-documented, not gloomy prognostications. Many pundits make their gravy by spouting dire predictions, but there is no one to hold them to account if they are inaccurate or flat-out lies. The voices of hysteria are still tooting like they hadn’t been repudiated at the ballot box.

I was asked recently, which sources of information I trust. I don’t trust any of them. I agree with Suzanne Massie, a scholar of Russian history: “Trust, but verify”. With historical research, a single source is insufficient, especially on controversial issues. As you dig deeper, you find a more three-dimensional view that often lays bare the simplistic assumptions of your primary source.

I cannot claim to have any particular insight into the first five weeks of the Trump Administration, but I look forward to seeing how it all turns out.

1. The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet, Simon & Schuster, 2014. Nina Teicholz

2. Margarine can also affect the nervous system and lead to depression and mental illness.

3. https://humanidades.com/en/structuralism/

4. D’où Venons Nous, Que Sommes Nous, Où Allons Nous — Paul Gauguin

5. Celui qui sauve sa patrie ne viole aucune loi—Maximes et pensées de Napoléon by Honoré de Balzac (1838), a compilation of aphorisms attributed to the emperor.

March 7, 2025

Trump marks the overdue end of the Long Twentieth Century, part 2

In The Conservative Woman, N.S. Lyons continues his essay contending that the arrival of Donald Trump, version 2.0, may finally end the era we’ve been living in since immediately after the end of WW2:

The Long Twentieth Century has been characterized by these three interlinked post-war projects: the progressive opening of societies through the deconstruction of norms and borders, the consolidation of the managerial state, and the hegemony of the liberal international order. The hope was that together they could form the foundation for a world that would finally achieve peace on earth and goodwill between all mankind. That this would be a weak, passionless, undemocratic, intricately micromanaged world of technocratic rationalism was a sacrifice the post-war consensus was willing to make.

That dream didn’t work out, though, because the “strong gods” refused to die.

Mary Harrington recently observed that the Trumpian revolution seems as much archetypal as political, noting that the generally “exultant male response to recent work by Elon Musk and his ‘warband’ of young tech-bros” in dismantling the entrenched bureaucracy is a reflection of what can be “understood archetypally as [their] doing battle against a vast, miasmic foe whose aim is the destruction of masculine heroism as such”. This masculine-inflected spirit was suppressed throughout the Long Twentieth Century, but now it’s back. And it wasn’t, she notes, “as though a proceduralist, managerial civilization affords no scope for horrors of its own”. Thus now “we’re watching in real time as figures such as the hero, the king, the warrior, and the pirate; or indeed various types of antihero, all make their return to the public sphere”.

Instead of producing a utopian world of peace and progress, the open society consensus and its soft, weak gods led to civilizational dissolution and despair. As intended, the strong gods of history were banished, religious traditions and moral norms debunked, communal bonds and loyalties weakened, distinctions and borders torn down, and the disciplines of self-governance surrendered to top-down technocratic management. Unsurprisingly, this led to nation-states and a broader civilization that lack the strength to hold themselves together, let alone defend against external threats from non-open, non-delusional societies. In short, the campaign of radical self-negation pursued by the post-war open society consensus functionally became a collective suicide pact by the liberal democracies of the Western world.

But, as reality began to intrude over the past two decades, the share of people still convinced by the hazy promises of the open society steadily diminished. A reaction began to brew, especially among those most divorced from and harmed by its aging obsessions: the young and the working class. The “populism” that is now sweeping the West is best understood as a democratic insistence on the restoration and reintegration of respect for those strong gods capable of grounding, uniting and sustaining societies, including coherent national identities, cohesive natural loyalties, and the recognition of objective and transcendent truths.

Today’s populism is more than just a reaction against decades of elite betrayal and terrible governance (though it is that too); it is a deep, suppressed desire for long-delayed action, to break free from the smothering lethargy imposed by proceduralist managerialism and fight passionately for collective survival and self-interest. It is the return of the political to politics. This demands a restoration of old virtues, including a vital sense of national and civilizational self-worth. And that in turn requires a rejection of the pathological “tyranny of guilt” (as the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner dubbed it) that has gripped the Western mind since 1945. As the power of endless hysterical accusations of “fascism” has gradually faded, we have – for better and worse – begun to witness the end of the Age of Hitler.

Bricking the internet

In The Line, Phil A. McBride explains how the “net giants” have steadily nibbled away at the built-in resilience of the original internet design so that we’re all far more vulnerable to network outages than ever before:

The Internet was originally conceived in the 1960s to be a resilient, disparate and distributed network that didn’t have any single point of failure. This is still true today. While there are large data centres around the world that aggregate traffic, we don’t depend on them. If one were to go offline, things would slow down, but the data would still flow.

The advent of the cloud, though, has completely changed how we use the Internet, especially in the worlds of business, education and government. And the cloud, alas, is not nearly as resilient.

Fifteen years ago, your average small or medium business would have their own servers. Those servers would be used to send/receive email, store files, and run various business or collaborative applications. Some of these servers may have been hosted offsite at a data centre to provide better security or speed of access, but the physical infrastructure belonged to someone — it was something you could touch and, more importantly, account for. Many companies kept their servers on site.

If a company’s server or network went down, it affected that company. They couldn’t send or receive email, they couldn’t open files, collaborate with staff or clients. They were offline.

But only they were offline.

Fast forward to today. Microsoft 365 dominates the corporate productivity services market with an estimated 45-50 per cent market share worldwide, with Google Workspace coming second, with around 30-35 per cent. This means that approximately 80 per cent of businesses are dependent on one of two vendors for their ability to transact business and communicate at even the most basic level.

Government and government-provided services, like education, health care and defence, are just as reliant on these services as the business world.

In today’s world, when Microsoft’s or Google’s services suffer a hiccup, it doesn’t affect one business. Or ten, or a hundred. Tens of thousands of business, and government offices and civil society institutions, all go offline. Simultaneously. Mom-and-pop stores, multi-billion-dollar corporations, elementary schools, hospitals, entire governments, all go out, all at once.

And we haven’t even talked about how Amazon, Microsoft and Google control almost two-thirds of the world’s web/application hosting market share. If one or all of those services go down, most of the websites you go to on a regular basis would suddenly become unreachable.

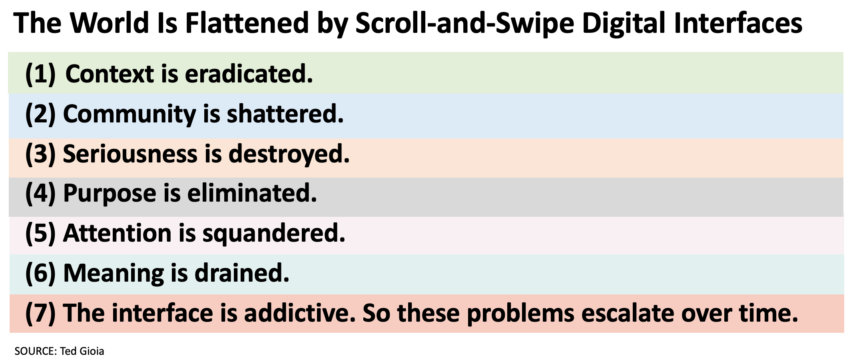

Kinda-sorta related to the above is Ted Gioia‘s “State of the Culture” post:

So remember the first rule: The culture always changes first. And then everything else adapts to it.

That’s why teens plugged into the most lowbrow culture often grasp the new reality long before elites figure it out. This was true 50 years ago, and it’s still true today.

So that’s our second rule: If you want to understand the emerging culture, look at the lives of teens and twenty-somethings — and especially their digital lives. (In some cases those are their only lives.)

The web has changed a lot in recent years, hasn’t it? Not long ago, the Internet was loose and relaxed. It was free and easy. It was fun. There wasn’t even an app store.

We made our own rules.

The web had removed all obstacles and boundaries. I could reach out to people all over the world.

The Internet, in those primitive days, put me back in touch with classmates from my youth. It reconnected me with friends I’d made during my many trips overseas. It strengthened my ties with relatives near and far. I even made new friends online.

It felt liberating. It felt empowering.

But it also helped my professional life. I had regular exchanges with writers and musicians in various cities and countries—without leaving the comfort of my home.

I made new connections. I opened new doors.

And this didn’t just happen to me. It happened to everybody.

“The world is flat,” declared journalist Thomas Friedman. All the barriers were gone — we were all operating on the same level. It felt like some imaginary Berlin Wall had fallen.

That culture of flatness changed everything. Ideas spread faster. Commerce moved more easily. Every day I encountered something new from some place far away.

But then it changed.

Twenty years ago, the culture was flat. Today it’s flattened.

I still participate in many web platforms — I need to do it for my vocation. (But do I really? I’ve started to wonder.) But now they feel constraining.

Even worse, they now all feel the same.

Instead of connecting with people all over the world, I now get “streaming content” 24/7.

Facebook no longer wants me stay in touch with friends overseas, or former classmates, or distant relatives. Instead it serves up memes and stupid short videos.

And they are the exact same memes and videos playing non-stop on TikTok — and Instagram, Twitter, Threads, Bluesky, YouTube shorts, etc.

Every big web platforms feels the exact same.

That whole rich tapestry of my friends and family and colleagues has been replaced by the most shallow and flattened digital fluff. And this feeling of flattening is intensified by the lack of context or community.

The only ruling principle is the total absence of purpose or seriousness.

The platforms aggravate this problem further by making it difficult to leave. Links are censored. Intelligence is punished by the dictatorship of the algorithms. Every exit is blocked, and all paths lead to the endless scroll.

All this should be illegal. But somehow it isn’t.

February 25, 2025

QotD: Identity politics as a secular religion

Tom Holland, in his book Dominion, The making of the Western Mind, identifies the “trace elements” of Christianity in the woke world. The example he used was the intersectional feminists in the #MeToo movement offering white feminists the chance to “acknowledge their own entitlement, to confess their sins and to be granted absolution”.

But the problem with identity politics as a secular religion is precisely its failure to allow for absolution. The faith that Saad espouses is utterly bleak, even cloaked as it is in words of love. It utterly fails to allow for redemption, and its most direct religious antecedent is found in Calvinist predestination.

Under this doctrine, God has predetermined whether you are damned or elect. From the second that the right sperm hit it lucky with the most fecund egg, your place in the woke hierarchy was decided. In the modern progressive world, informed by intersectional feminists, it does not matter what you say or do, the only defining factor in your state of grace is your skin, gender and sexuality.

This is a profoundly depressing outlook for three main reasons. The first is the essential nihilism in the creed. Your intent? Irrelevant. Your deeds? Likewise. The sum of your experience, desires, longings, beliefs? Your humanity itself? Nah, not relevant.

The second dispiriting message is that the problems its aims to address are insoluble. White people are racist by their nature, and inherently incapable of seeing their own racism or addressing it. Men are misogynists, by default, witting or unwitting bulwarks of the patriarchy. If they don’t believe they are individually at fault they are in denial. And if they try to say, actually, I’m not sure the patriarchy exists, they are mansplaining misogynist bastards. This is the politics of perpetual antagonism, of a kind of bleak acceptance that all relationships between different categories of human are necessarily fractious.

[…]

The third problem with Puritan wokeness is that it [has] sinister echoes in the history of predestination. When the creed reached its zenith in the seventeenth century, the logical hole at its centre became insanely obvious. If it does not matter to God how you behave, because your salvation was pre-determined at birth, why not behave however the hell you want to?

Antonia Senior, “Identity politics is Christianity without the redemption”, UnHerd, 2020-01-20.

February 16, 2025

QotD: Why we’re stagnating

I won’t attempt to recap here the many arguments that have been made recently about whether and how our society is stagnating. You could read this book or this book or this book. Or you could look at how economic productivity has stalled since 1971. Or you could puzzle over what else happened in 1971. Or you could read Patrick Collison’s list of how fast things used to happen, or ponder how practically every new movie these days is a sequel, or stare in shock at declines in scientific productivity. This new book by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber starts with a survey of the most damning indicators of stagnation, moves on to suggest some underlying causes, and then suggests an unexpected way out.

Their explanation for our doldrums is simple: we’re more risk averse, and we don’t care as much about the future. Risk aversion means stagnation, because any attempt to make things better involves risk: it could also make things worse, or it could fail and turn out to be a waste of time and money. Trying to invent a crazy new technology is risky, going into consulting or finance is safe. Investing in unproven startups or speculative bets is risky, investing in index funds is safe. Trying to overturn the scientific consensus is risky, keeping your head down and publishing papers that don’t say anything is safe. Producing challenging new art is risky, spewing an endless stream of Marvel superhero capeshit is safe. Even if, in every case, the safe option is the “rational” choice for an individual actor in maximin expected value terms, the sum total of these individually rational choices is a catastrophe for society.

So far this is a lame, almost tautological, explanation. Even if it’s all true, we still haven’t explained why people are so much more fearful of failure than they used to be. In fact, we would naively assume the opposite — society is much richer now, social safety nets much more robust, and in the industrialized world even the very poor needn’t fear starvation. In a very real sense, it’s never been safer to take risks. Failing as a startup founder or academic means you experience slightly lower lifetime earnings,1 while, in the great speculative excursions of the past, failure (and sometimes even success) meant death, scurvy, amputations, destitution, children sold into slavery or raised in poorhouses — basically unbounded personal catastrophe. And yet we do it less and less. Why?

Well, for starters, we aren’t the same people. Biologically, that is. We’re old, and old people tend to be more risk-averse in every way. Old people have more to lose. Old people also have less testosterone in their bloodstream. The population structure of our society has shifted drastically older because we aren’t having any children. This not only increases the relative number (and hence relative power) of older people, it also has direct effects on risk-aversion and future-orientation. People with fewer children have all their eggs in fewer baskets. They counsel those kids to go into safe professions and train them from birth to be organization kids. People with no children at all are disconnected from the far future, reinforcing the natural tendency of the elderly to favor consumption in the here and now over investment in a future they may never get to enjoy.

Old age isn’t the only thing that reduces testosterone levels. So does just living in the 21st century. The declines are broad-based, severe, and mysterious. Very plausibly they are downstream of microplastics and other endocrine-disrupting chemicals. The same chemicals may have feminizing effects beyond declines in serum testosterone. They could also be affecting the birth rate, one of many ways that these explanations all swirl around and flow into one another. Or maybe we don’t even need to invoke old age and microplastics to explain the decline in average testosterone of decisionmakers in our society. Many more of those decisionmakers are women, and women are vastly more risk-averse on average.2

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Boom, by Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-11-11.

1. And given the logarithmic hedonic utility of additional money and fame, that hurts even less than it sounds like it would.

2. If you’re too lazy to read Jane’s review of Bronze Age Mindset but just want the evidence that women are more cautious and consensus-seeking than men on average, try this and this and this for starters.

February 15, 2025

“Trump marks the overdue end of the Long Twentieth Century”

At The Upheaval, N.S. Lyons suggests that the arrival of Donald Trump, version 2.0, may finally end the era we’ve been living in since immediately after the end of WW2:

The 125 years between the French Revolution in 1789 and the outbreak of WWI in 1914 was later described as the “Long Nineteenth Century”. The phrase recognized that to speak of “the nineteenth century” was to describe far more than a specific hundred-year span on the calendar; it was to capture the whole spirit of an age: a rapturous epoch of expansion, empire, and Enlightenment, characterized by a triumphalist faith in human reason and progress. That lingering historical spirit, distinct from any before or after, was extinguished in the trenches of the Great War. After the cataclysm, an interregnum that ended only with the conclusion of WWII, everything about how the people of Western civilization perceived and engaged with the world – politically, psychologically, artistically, spiritually – had changed.

R.R. Reno opens his 2019 book Return of the Strong Gods by quoting a young man who laments that “I am twenty-seven years old and hope to live to see the end of the twentieth century”. His paradoxical statement captures how the twentieth century has also extended well past its official sell-by date in the year 2000. Our Long Twentieth Century had a late start, fully solidifying only in 1945, but in the 80 years since its spirit has dominated our civilization’s whole understanding of how the world is and should be. It has set all of our society’s fears, values, and moral orthodoxies. And, through the globe-spanning power of the United States, it has shaped the political and cultural order of the rest of the world as well.

The spirit of the Long Twentieth could not be more different from that which preceded it. In the wake of the horrors inflicted by WWII, the leadership classes of America and Europe understandably made “never again” the core of their ideational universe. They collectively resolved that fascism, war, and genocide must never again be allowed to threaten humanity. But this resolution, as reasonable and well-meaning as it seemed at the time, soon became an all-consuming obsession with negation.

Hugely influential liberal thinkers like Karl Popper and Theodor Adorno helped convince an ideologically amenable post-war establishment that the fundamental source of authoritarianism and conflict in the world was the “closed society”. Such a society is marked by what Reno dubs “strong gods”: strong beliefs and strong truth claims, strong moral codes, strong relational bonds, strong communal identities and connections to place and past – ultimately, all those “objects of men’s love and devotion, the sources of the passions and loyalties that unite societies”.

Now the unifying power of the strong gods came to be seen as dangerous, an infernal wellspring of fanaticism, oppression, hatred, and violence. Meaningful bonds of faith, family, and above all the nation were now seen as suspect, as alarmingly retrograde temptations to fascism. Adorno, who set the direction of post-war American psychology and education policy for decades, classified natural loyalties to family and nation as the hallmarks of a latent “authoritarian personality” that drove the common man to xenophobia and führer worship. Popper, in his sweepingly influential 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, denounced the idea of national community entirely, labeling it as disastrous “anti-humanitarian propaganda” and smearing anyone who dared cherish as special his own homeland and history as a dangerous “racialist”. For such intellectuals, any definitive claim to authority or hierarchy, whether between men, morals, or metaphysical truths, seemed to stand as a mortal threat to peace on earth.

The great project of post-war establishment liberalism became to tear down the walls of the closed society and banish its gods forever. To be erected on its salted ground was an idyllic but exceptionally vague vision of an “open society” animated by peaceable weak gods of tolerance, doubt, dialogue, equality, and consumer comfort. This politically and culturally dominant “open society consensus” drew on theorists like Adorno and Popper to advance a program of social reforms intended to open minds, disenchant ideals, relativize truths, and weaken bonds.

As Reno catalogues in detail, new approaches to education, psychology, and management sought to relativize truths, elevate “critical thinking” over character, vilify collective loyalties, cast doubt on hierarchies, break down all boundaries and borders, and free individuals from the “repression” of all moral and relational duties. Aspiration to a vague universal humanitarianism soon became the only higher good that it was socially acceptable to aim for other than pure economic growth.

[…]

The Long Twentieth Century has been characterized by these three interlinked post-war projects: the progressive opening of societies through the deconstruction of norms and borders, the consolidation of the managerial state, and the hegemony of the liberal international order. The hope was that together they could form the foundation for a world that would finally achieve peace on earth and goodwill between all mankind. That this would be a weak, passionless, undemocratic, intricately micromanaged world of technocratic rationalism was a sacrifice the post-war consensus was willing to make.

That dream didn’t work out though, because the strong gods refused to die.

Update, 17 February: Welcome Instapundit readers! Thanks for dropping by. Please do look around at some of my other posts! I think the last time I got linked by Instapundit was back in 2008/9 just before I moved to the current location. Please do read the entire N.S. Lyons post, as this is just a taster of the full essay!

February 14, 2025

Trump may start paying attention to Canadian cultural protectionist polices next

Michael Geist points out just how many Canadian federal policies and programs will likely come under scrutiny by the Trump administration for their blatant protectionism against US cultural products:

My Globe and Mail op-ed argues the need for change is particularly true for Canadian digital and cultural policy. Parliamentary prorogation ended efforts at privacy, cybersecurity and AI reforms and U.S. pressure has thrown the future of a series of mandated payments – digital service taxes, streaming payments and news media contributions – into doubt. But the Trump tariff escalation, which now extends to steel and aluminum as well as the prospect of reviving the original tariff plan in a matter of weeks, signals something far bigger that may ultimately render current Canadian digital and cultural policy unrecognizable.

Our cultural frameworks are largely based on decades-old policies premised on marketplace protections and mandated support payments. This included foreign ownership restrictions in the cultural sector and requirements that broadcasters contribute a portion of their revenues to support Canadian content production.

As we moved from an analog to digital world, the government simply extended those policies to the digital realm. But with Mr. Trump appearing to call out what he views to be Canadian protectionist policies in sensitive sectors such as banking ownership, the cultural and digital sectors may be next.

If so, there are no shortage of long-standing policies that tilt the playing field in favour of Canadians that could spark some uncomfortable conversations.

Why do U.S. companies face ownership restrictions in the telecom and broadcast sectors? Why are Canadian broadcasters permitted to block U.S. television signals in order to capture increased advertising revenue? Why do Canadian content rules exclude U.S. companies from owning productions featuring predominantly Canadian talent?

The Canadian response that this is how it has always been is unlikely to persuade Mr. Trump.

Canadian policies premised on “making web giants pay” may also be non-starters under Mr. Trump. For the past five years, the Canadian government seemingly welcomed the opportunity to sabre rattle with U.S. internet companies. This led to mandated payments for streaming services to support Canadian film, television and music production; link taxes that targeted Meta and Google to help Canadian news outlets; and the multibillion-dollar retroactive digital services tax that is primarily aimed at U.S. tech giants.

Not only have those policies raised consumer affordability and marketplace competition concerns, they have also emerged as increasingly contentious trade issues. If the trade battles with the U.S. continue, the pressure to scale back the policies will mount.

Beyond rethinking established cultural and digital policies both new and old, the bigger changes may come from re-evaluating the competitive impact of policies that rely heavily on regulation just as the U.S. prioritizes economic growth through deregulation. Proposed Canadian privacy, online harms and AI rules have all relied heavily on increased regulation, looking to Europe as the model.

For example, consider the Canadian approach to AI regulation in the now-defunct Artificial Intelligence and Data Act. It specifically referenced the European Union’s regulatory system, which establishes extensive regulatory requirements for high-risk AI systems and bans some AI systems altogether.

However, the European approach is not the only game in town. Mr. Trump moved swiftly to cancel the former Biden administration’s executive order on AI regulation, signalling that the U.S. will prioritize deregulation in pursuit of global AI leadership. Further, the arrival of DeepSeek, the Chinese answer to ChatGPT, took the world by storm and served notice that U.S. AI dominance is by no means guaranteed.

The competing approaches – U.S.-style lightweight regulation that favours economic growth against a more robust European regulatory model that emphasizes AI guardrails and public protections – will force difficult policy choices that Canada has thus far avoided.

QotD: “Galentine’s Day”

My other moment of Argh was occasioned by younger son. No, that doesn’t mean younger son did something wrong. He didn’t. It’s more that younger son told me about something. (Oh, dear Lord, why does he do that?) and what he told me about was that some show introduced the concept of “Galentine’s” on the 13th. This is a day for “ladies to celebrate ladies”. What was driving younger son bananas (with a side of kiwi) is that he seeing all his female friends fall into this.

The idea is frankly loony. Valentine’s itself is highly commercialized, but most of the time, my husband I circumvent it by having walks together, or just watching a movie together. However, a day to celebrate being a couple is useful (and it wasn’t proclaimed by some government. In fact, I’m fairly sure what it is in the US grew organically, because it’s not the same anywhere else. In Portugal it’s considered “boyfriend/girlfriend day” but it mostly amounts to some kissing and maybe flowers. Or it did in my day.) Trust me, in the years of raising toddlers, any time to remember yes, you’re in love, and what brought you together is important.

But Galentine? What the actual heck? It’s not bonding, and it’s not building a relationship that is a cornerstone of society. No. It’s … putting up lists of your friends who are female and celebrating them BECAUSE THEY’RE FEMALE. This is something they were born, and can’t help being, and … what are we celebrating, precisely?

It’s not that I object to “ugly/awkward girls get a day too.” No. It’s the undertones of it. It’s the “It’s just as good to be a woman as a couple (you know, the future would beg to differ) and how being a woman is something you should celebrate because … because … because … I don’t know? Because we have vaginas?

Picture guys saying that being a man is something to celebrate, because … they have penises? Mind you, I’m a big fan of both men and their ah implement, but seriously? It would be laughable. And celebrating because you’re a woman is equally laughable.

Mind you, I’m probably the voice crying in the wilderness in the days of pussy hats and women marching around with signs painted with vulvas or proudly proclaiming they have a vulva, but it seems to me if what makes you special is the non-thinking thing between your legs, you’re doing life wrong, you’re doing equality wrong and MOST importantly, you’re doing SPECIAL wrong.

Sarah Hoyt, “Dance To The Music”, According to Hoyt, 2017-02-14.

January 29, 2025

Canadians – “polite lunatics”

In The Line, Mitch Heimpel talks about a Canadian culture from a time before a Canadian PM could get away with maligning the country as having “no core identity”:

In recent days, The Line has spoken of the need for Canada to go “full psycho”. To “Make ‘Canada’s back’ a threat”. And, specifically, to recapture a Canadian identity that was, not long ago, widely shared — Canadians as scary and even dangerous. My own mind had been on similar topics of late, and I’d been thinking, specifically, about how those representations used to show up not just in our pop culture, but in American pop culture.

And in at least one place, you can find it still: Shoresy, a hilarious comedy show about Canadian hockey hosers that has found success on both sides of the border.

Shoresy is interesting not because it’s new, but almost because it’s retro. Once upon a time, the kind of Canadian identity shown in Shoresy was just … Canadian identity. Here’s a great example of what I mean that I suspect many readers will have seen: 1968’s The Devil’s Brigade, a film about the First Special Service Force, a joint Canadian-American unit that would become the forerunner to the American Green Berets. The film is a remarkable reflection of the attitudes that the two cultures had about each other. In one particular scene, after the Americans (predominantly tough guy actors Claude Akins and James Coburn) have spent days making sport of the Canadians, a new Canadian sergeant — played by Jeremy Slate — is introduced in a mess hall scene. Mild-mannered, lithe, and even bespectacled, the Sergeant sits down next to Akins and begins to insult him. He starts by literally elbowing the American bully for room at the table in the Mess and proceeds to call him a fat tub of lard.

Once Akins has had enough, he attacks the Canadian sergeant, who reveals himself to be the unit’s new hand-to-hand combat instructor, and proceeds to pummel Akins while barely smudging his glasses. After having bruised the American’s body, as well as his ego, he returns to dinner and punctuates it by asking Akins for the salt. Akins hands it over.

This was not a remarkable representation. The Americans used to view us as polite lunatics. This showed up not just in American media, but also our stories about ourselves. Characters like Slate’s sergeant Patrick O’Neill showed up in the songs of Stompin’ Tom, Ian Tyson, and even Gordon Lightfoot. They’re memorialized in the works of Robert Service and Al Purdy. Purdy, in particular, describes this archetype well, both in At the Quinte Hotel and in The Country North of Belleville:

backbreaking days

in the sun and rain

when realization seeps slow in the mind

without grandeur or self-deception in

noble struggle

of being a fool –A country of quiescence and still distance

a lean land

not like the fat south.In those few lines, Purdy captures Canadiana so easily. A people shaped by distance and the harshness of the land. Capable of the toughness needed to endure. With just a little foolishness mixed in for good measure.

Polite lunatics.

January 14, 2025

QotD: Ritual in medieval daily life

I am not in fact claiming that medieval Catholicism was mere ritual, but let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that it was — that so long as you bought your indulgences and gave your mite to the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever and showed up and stayed awake every Sunday as the priest blathered incomprehensible Latin at you, your salvation was assured, no matter how big a reprobate you might be in your “private” life. Despite it all, there are two enormous advantages to this system:

First, n.b. that “private” is in quotation marks up there. Medieval men didn’t have private lives as we’d understand them. Indeed, I’ve heard it argued by cultural anthropology types that medieval men didn’t think of themselves as individuals at all, and while I’m in no position to judge all the evidence, it seems to accord with some of the most baffling-to-us aspects of medieval behavior. Consider a world in which a tag like “red-haired John” was sufficient to name a man for all practical purposes, and in which even literate men didn’t spell their own names the same way twice in the same letter. Perhaps this indicates a rock-solid sense of individuality, but I’d argue the opposite — it doesn’t matter what the marks on the paper are, or that there’s another guy named John in the same village with red hair. That person is so enmeshed in the life of his community — family, clan, parish, the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever — that “he” doesn’t really exist without them.

Should he find himself away from his village — maybe he’s the lone survivor of the Black Death — then he’d happily become someone completely different. The new community in which he found himself might start out as “a valley full of solitary cowboys”, as the old Stephen Leacock joke went — they were all lone survivors of the Plague — but pretty soon they’d enmesh themselves into a real community, and red-haired John would cease to be red-haired John. He’d probably literally forget it, because it doesn’t matter — now he’s “John the Blacksmith” or whatever. Since so many of our problems stem from aggressive, indeed overweening, assertions of individuality, a return to public ritual life would go a long way to fixing them.

The second huge advantage, tied to the first, is that community ritual life is objective. Maybe there was such a thing as “private life” in a medieval village, and maybe “red-haired John” really was a reprobate in his, but nonetheless, red-haired John performed all his communal functions — the ones that kept the community vital, and often quite literally alive — perfectly. You know exactly who is failing to hold up his end in a medieval village, and can censure him for it, objectively — either you’re at mass or you’re not; either you paid your tithe or you didn’t; and since the sacrament of “confession” took place in the open air — Cardinal Borromeo’s confessional box being an integral part of the Counter-Reformation — everyone knew how well you performed, or didn’t, in whatever “private” life you had.

Take all that away, and you’ve got process guys who feel it’s their sacred duty — as in, necessary for their own souls’ sake — to infer what’s going on in yours. Strip away the public ritual, and now you have to find some other way to make everyone’s private business public … I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Calvinism is really Karen-ism, and if it IS unfair, I don’t care, because fuck Calvin, the world would’ve been a much better place had he been strangled in his crib.

A man is only as good as the public performance of his public duties. And, crucially, he’s no worse than that, either. Since process guys will always pervert the process in the name of more efficiently reaching the outcome, process guys must always be kept on the shortest leash. Send them down to the countryside periodically to reconnect with the laboring masses …

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.