Tasting History with Max Miller

Published May 21, 2024D-Day Scrambled Eggs and Bacon served with toast and D-Day Lemonade

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1944The food in the final days leading up to D-Day was a definite improvement over the sad, dry sandwiches some soldiers had been getting. All-you-can-eat meals of steak, pork chops, sides, lemon meringue pie, ice cream, and even popcorn and candy during movie screenings kept the sequestered troops well fed. The last meal served before the landing was breakfast in the very early hours of the morning, said by many to be scrambled eggs and bacon.

This meal was made in the south of England, but the bacon was from the U.S., so American-style bacon is best here. The eggs don’t taste bad, but the texture is not like fresh scrambled eggs at all (more like tofu). The bacon is real, though, and that really saves the dish. Powdered eggs can be found online and at camping stores.

No. 749. Scrambled Eggs

Water, cold … 2 1/2 quarts (2 1/2 No. 56 dippers)

Eggs, powdered … 1 1/2 pounds (1/2 3-pound can)

Salt … To taste

Pepper … To taste

Lard or bacon fat … 1 pound (1/2 No. 56 dipper)Sift eggs. Pour 1/3 of the water into a utensil suitable for mixing eggs. Add powdered eggs. Stir vigorously with whip or slit spoon until mixture is absolutely smooth. Tip utensil while stirring.

Add salt, pepper, and remaining water slowly to eggs, stirring until eggs are completely dissolved.

Melt fat in baking pan. Pour liquid eggs into hot fat.

Stir as eggs begin to thicken. Continue stirring slowly until eggs are cooked slightly less than desired for serving.

Take eggs from fire while soft, as they will continue to thicken after being removed from heat.No. 750. Diced Ham (or Bacon) and Scrambled Eggs

Add 3 pounds of ham or bacon to basic recipe for scrambled eggs; omit lard. Fry ham or bacon until crisp and brown.

Pour egg solution over meat and fat. Stir and cook as in basic recipe. Additional fat may be needed if ham is used.

— TM 10-412 US Army Technical Manual. Army Recipes by the U.S. War Department, 1946

June 5, 2024

What Troops Ate On D-Day – World War 2 Meals & Rations

June 1, 2024

May 28, 2024

Why a Tire Company Gives Out Food’s Most Famous Award

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Feb 20, 2024Eugénie Brazier, the chef behind today’s recipe, was a culinary force to be reckoned with. She was described as “a formidable woman with a voice like a foghorn, rough language, and strong forearms”. Both of her restaurants won Michelin stars in the early 20th century, making her the first person to have six. No one else would earn six Michelin stars for 64 years.

By modern Michelin standards, this dish is pretty plain, but it’s still really good. The chicken is cooked simply in butter, and the cream sauce is absolutely fantastic. I was afraid the alcohol would overpower it, but it doesn’t. The sauce takes on a kind of floral woodiness instead of each individual alcohol’s flavor, and it’s so good.

(more…)

May 23, 2024

The Roman Colosseum: What It Was Like to Attend the Games

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Feb 13, 2024Like at sports events today, you could get snacks and souvenirs in and around the Colosseum in ancient Rome. There were sausages and pastries and small sweet snacks, like these dates. Not the same as modern hot dogs and soft serve, but kind of in the same spirit.

These dates are really, really good. You could grind the nuts into a fine paste, but I like the texture a lot when they’re left a little coarse. They’re very sweet from the dates and the honey, but the salt and pepper balance it so well (highly recommend the long pepper here). Definitely give these a try!

(more…)

May 17, 2024

Deviled Bones – The History of Hot Wings

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Feb 6, 2024[Information from the Tasting History page for this video]

Chicken wings tossed in a spicy, complex sauce featuring mushroom ketchup.

The history of hot wings goes much further back than 1964 in Buffalo, New York, as a Google search might have you believe. Deviled bones were a way to use up undesirable chicken wings for centuries before that, calling for leftover cooked joints that still had some meat on them (the bones), and flavorful spices (deviled).

If you’re not a lover of spicy things, like me, then the 1/4 teaspoon of cayenne is plenty. That said, feel free to adjust the amounts of any of the spices to suit your taste. I was afraid that the mustard would be overpowering, but it isn’t. The flavor is complex and full of umami thanks to the mushroom ketchup. This is an easy recipe to do some prep work the day before, as the wings would have originally been leftovers.

Devilled Bones

Take the bones of any remaining joint or poultry, which has still some meat on, which cut across slightly, and then make a mixture of mustard, salt, cayenne, and pepper, and one teaspoonful of mushroom ketchup to two of mustard; rub the bones well with this, and broil rather brownish.

— A Shilling Cookery for the People by Alexis Soyer, 1854.

May 10, 2024

Table Manners in the Ottoman Empire – Acem Pilaf

Text from https://www.tastinghistory.com/recipes/ottomanpilaf:

At an Ottoman banquet, you were only ever meant to eat a few bites of each dish that was brought out (having more was seen as being greedy). But there was no danger of leaving the table hungry, as there could be upwards of dozens of dishes. To European visitors, the order that the dishes were brought out in made no sense. Cakes could be brought out between meat courses, a rich pastry brought out after fish, and fowl after chocolate cake. Amidst this seeming chaos, pilaf was always the last dish served.

Let’s address the elephant in the room and state that yes, the pilaf is supposed to come out layered and all in one piece, but mine did not. Ottoman dishes were meant to be not only flavorful, but beautiful as well. That being said, even if you mold yours in a separate container like I did, it is still delicious (and quite nice looking). The warm spices are a wonderful and unusual combination with the lamb (at least to my palate), and there is a fantastic array of textures.

“Chop a piece of good mutton into small pieces, place them in a pot … add one or two spoonfuls of fresh butter and after frying, take the cooked meat from the pot with a hand strainer. Finely chop three or four onions and fry them, then put the roasted meat on top. Then add plenty of pistachios, currants, cinnamon, cloves, and cardamom on top. After that, according to the old method, one measure of washed Egyptian rice. Add two measures of cold water without disturbing the rice, add sufficient salt, then close the lid of the pot and cover it thoroughly with dough. Boil it slowly on coals and when the water is absorbed, take the cover off, and turn the contents out of the pan onto a dish so it comes out intact. This makes a Pilaw that is very pleasing to the sight, and exceedingly pleasant to the taste.”

— Melceü’t-Tabbâhîn, 1844

May 1, 2024

Lobscouse, Hardtack & Navy Sea Cooks

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jan 23, 2024Hearty meat and potato stew thickened with crushed hardtack (clack clack)

April 19, 2024

Breakfast in Jane Austen’s England

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jan 16, 2024What you could tell about someone from their breakfast in Jane Austen’s England, and a recipe for Bath buns as she might have eaten them for her first meal of the day.

Caraway buns topped with glaze, sugar, and caraway, served with butter. Perfect for a Jane Austen inspired breakfast with some hot chocolate

City/Region: England

Time Period: 1769It is a truth universally acknowledged that a person who has recently risen from bed must be in want of breakfast. In Jane Austen’s time, breakfast could be around 8:00 or 9:00 in the morning if you were a manual laborer or servant, or it could be as late as 3:00 or 4:00 in the afternoon if you were upper class.

Jane wrote a letter to her sister Cassandra saying that she wanted to join her on her trip to Bath, but didn’t want to inconvenience their hosts, so she would fill up on bath buns for breakfast. I can see why this would have been a sound strategy. The buns are denser than modern versions, but still soft and very good (they would certainly fill you up). The caraway is present but not overpowering, and they’re sweet but not as sweet as a dessert.

Caraway comfits were candy-coated caraway seeds (think M&Ms), but they don’t use caraway to make them anymore. I mimic them as best I can with caraway seeds and sugar.

To make Bath Cakes.

Rub half a pound of butter into a pound of flour, and one spoonful of good barm, warm some cream, and make it into a light paste, set it to the fire to rise, when you make them up, take four ounces of carraway comfits work part of them in, and strew the rest on the top, make them into a round cake, the size of a French roll, bake them on sheet tins, and send them in hot for breakfast.

— The Experienced English Houskeeper by Elizabeth Raffald, 1769

April 13, 2024

The Legend of the Wiener Schnitzel

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jan 9, 2024Variations of wienerschnitzel throughout history and its legendary origin stories, and a recipe for a 19th century version.

Fried breaded veal cutlets served with the traditional lemon wedges and parsley

City/Region: Vienna

Time Period: 1824Breaded and fried meat has been around for a very long time in many places, but it wasn’t until 1893 that we get the first mention of the word wienerschnitzel. Then in the early 20th century, the Austrian culinary scene decided to champion this term to refer to a veal cutlet that is made into a schnitzel, and restaurants in Vienna began specializing in schnitzel.

This recipe predates the term wienerschnitzel, and unlike modern versions it isn’t dredged in flour first. This makes it so that the breading doesn’t puff away from the meat, but the flavor is rich and delicious, just like I remember from my trip to Vienna. If you don’t like veal or don’t want to use it, you can use pork or chicken. It won’t technically be wienerschnitzel, but nobody’s going to judge you. You can also use another fat instead of the clarified butter, but butter gives the best flavor.

(more…)

April 10, 2024

QotD: Aprons

It’s like the thing with the aprons, that science fiction writers older than I think that Heinlein was a sexist, because he has women wearing aprons. Instead of “Everyone who worked with staining liquids and fire wore aprons. Because clothes were insanely expensive, that’s why.” We stopped wearing aprons [because today] a pack of t-shirts at WalMart is $10. Nothing to do with sexism.

Sarah Hoyt, “Teaching Offense”, According to Hoyt, 2019-10-25.

April 6, 2024

The Fake (and real) History of Potato Chips

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jan 2, 2024The fake and true history of the potato chip and an early 19th century recipe for them. Get the recipe at my new website https://www.tastinghistory.com/ and buy Fake History: 101 Things that Never Happened: https://lnk.to/Xkg1CdFB

(more…)

March 28, 2024

The History of Fish Sauce – Garum and Beyond!

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Dec 26, 2023Sweet frittata-like patina of pears with classic ancient Roman flavors and sprinkled with long pepper

City/Region: Rome

Time Period: 1st CenturyThis patina de piris is one of over a dozen recipes for similar dishes in Apicius’ De re coquinaria, a staple for ancient Roman recipes. It would have probably been part of mensa secunda, or second meal. Not a second breakfast, it was the final course in a larger meal and usually consisted of sweets, pastries, nuts, and egg dishes, kind of like a modern dessert course.

I finally made my own true ancient Roman garum in the summer of 2023, from chopped up fish pieces and salt to clear amber umami-laden liquid. There’s no fishiness in this surprisingly sweet dish, just a saltiness and savory umami notes that complements the other very ancient Roman flavors.

As with all ancient recipes, this is my interpretation and you can change things up how you like. I separated my eggs before beating them, but you could just whisk them up whole and add them like that.

(more…)

March 13, 2024

The History of the Chocolate Chip Cookie – Depression vs WW2

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Dec 5, 2023WWII ration-friendly chocolate chip cookies made with shortening, honey, and maple syrup

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1940sDuring WWII, everyone in the US wanted to send chocolate chip cookies to the boys at the front. With wartime rationing in effect, we get a recipe that doesn’t use butter or sugar, but shortening, honey, and maple syrup instead.

The dough is much softer than the original version, and the cookies spread out a lot more as they bake. They bake up softer than the crunchy originals, with a light pillowy texture. They aren’t as sweet, but still have a really lovely flavor. It kind of reminds me of Raisin Bran, but with chocolate. All in all, I was pleasantly surprised.

Check out the episode to see a side-by-side comparison with the original recipe.

(more…)

March 9, 2024

Salt – mundane, boring … and utterly essential

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at the importance of salt in history:

There was a product in the seventeenth century that was universally considered a necessity as important as grain and fuel. Controlling the source of this product was one of the first priorities for many a military campaign, and sometimes even a motivation for starting a war. Improvements to the preparation and uses of this product would have increased population size and would have had a general and noticeable impact on people’s living standards. And this product underwent dramatic changes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, becoming an obsession for many inventors and industrialists, while seemingly not featuring in many estimates of historical economic output or growth at all.

The product is salt.

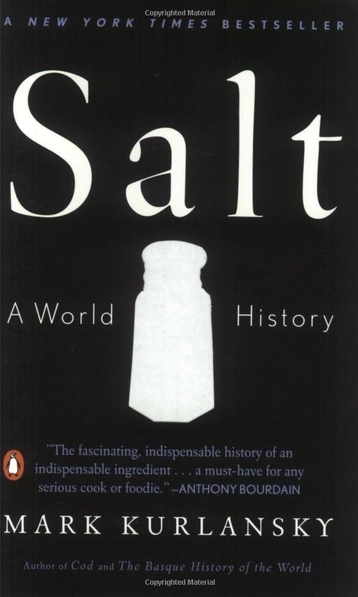

Making salt does not seem, at first glance, all that interesting as an industry. Even ninety years ago, when salt was proportionately a much larger industry in terms of employment, consumption, and economic output, the author of a book on the history salt-making noted how a friend had advised keeping the word salt out of the title, “for people won’t believe it can ever have been important”.1 The bestselling Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky, published over twenty years ago, actively leaned into the idea that salt was boring, becoming so popular because it created such a surprisingly compelling narrative around an article that most people consider commonplace. (Kurlansky, it turns out, is behind essentially all of those one-word titles on the seemingly prosaic: cod, milk, paper, and even oysters).

But salt used to be important in a way that’s almost impossible to fully appreciate today.

Try to consider what life was like just a few hundred years ago, when food and drink alone accounted for 75-85% of the typical household’s spending — compared to just 10-15%, in much of the developed world today, and under 50% in all but a handful of even the very poorest countries. Anything that improved food and drink, even a little bit, was thus a very big deal. This might be said for all sorts of things — sugar, spices, herbs, new cooking methods — but salt was more like a general-purpose technology: something that enhances the natural flavours of all and any foods. Using salt, and using it well, is what makes all the difference to cooking, whether that’s judging the perfect amount for pasta water, or remembering to massage it into the turkey the night before Christmas. As chef Samin Nosrat puts it, “salt has a greater impact on flavour than any other ingredient. Learn to use it well, and food will taste good”. Or to quote the anonymous 1612 author of A Theological and Philosophical Treatise of the Nature and Goodness of Salt, salt is that which “gives all things their own true taste and perfect relish”. Salt is not just salty, like sugar is sweet or lemon is sour. Salt is the universal flavour enhancer, or as our 1612 author put it, “the seasoner of all things”.

Making food taste better was thus an especially big deal for people’s living standards, but I’ve never seen any attempt to chart salt’s historical effects on them. To put it in unsentimental economic terms, better access to salt effectively increased the productivity of agriculture — adding salt improved the eventual value of farmers’ and fishers’ produce — at a time when agriculture made up the vast majority of economic activity and employment. Before 1600, agriculture alone employed about two thirds of the English workforce, not to mention the millers, butchers, bakers, brewers and assorted others who transformed seeds into sustenance. Any improvements to the treatment or processing of food and drink would have been hugely significant — something difficult to fathom when agriculture accounts for barely 1% of economic activity in most developed economies today. (Where are all the innovative bakers in our history books?! They existed, but have been largely forgotten.)

And so far we’ve only mentioned salt’s direct effects on the tongue. It also increased the efficiency of agriculture by making food last longer. Properly salted flesh and fish could last for many months, sometimes even years. Salting reduced food waste — again consider just how much bigger a deal this used to be — and extended the range at which food could be transported, providing a whole host of other advantages. Salted provisions allowed sailors to cross oceans, cities to outlast sieges, and armies to go on longer campaigns. Salt’s preservative properties bordered on the necromantic: “it delivers dead bodies from corruption, and as a second soul enters into them and preserves them … from putrefaction, as the soul did when they were alive”.2

Because of salt’s preservative properties, many believed that salt had a crucial connection with life itself. The fluids associated with life — blood, sweat and tears — are all salty. And nowhere seemed to be more teeming with life as the open ocean. At a time when many believed in the spontaneous generation of many animals from inanimate matter, like mice from wheat or maggots from meat, this seemed a more convincing point. No house was said to generate as many rats as a ship passing over the salty sea, while no ship was said to have more rats than one whose cargo was salt.3 Salt seemed to have a kind of multiplying effect on life: something that could be applied not only to seasoning and preserving food, but to growing it.

Livestock, for example, were often fed salt: in Poland, thanks to the Wieliczka salt mines, great stones of salt lay all through the streets of Krakow and the surrounding villages so that “the cattle, passing to and fro, lick of those salt-stones”.4 Cheshire in north-west England, with salt springs at Nantwich, Middlewich and Northwich, has been known for at least half a millennium for its cheese: salt was an essential dietary supplement for the milch cows, also making it (less famously) one of the major production centres for England’s butter, too. In 1790s Bengal, where the East India Company monopolised salt and thereby suppressed its supply, one of the company’s own officials commented on the major effect this had on the region’s agricultural output: “I know nothing in which the rural economy of this country appears more defective than in the care and breed of cattle destined for tillage. Were the people able to give them a proper quantity of salt, they would … probably acquire greater strength and a larger size.”5 And to anyone keeping pigeons, great lumps of baked salt were placed in dovecotes to attract them and keep them coming back, while the dung of salt-eating pigeons, chickens, and other kept birds were considered excellent fertilisers.6

1. Edward Hughes, Studies in Administration and Finance 1558 – 1825, with Special Reference to the History of Salt Taxation in England (Manchester University Press, 1934), p.2

2. Anon., Theological and philosophical treatise of the nature and goodness of salt (1612), p.12

3. Blaise de Vigenère (trans. Edward Stephens), A Discovrse of Fire and Salt, discovering many secret mysteries, as well philosophical, as theological (1649), p.161

4. “A relation, concerning the Sal-Gemme-Mines in Poland”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 5, 61 (July 1670), p.2001

5. Quoted in H. R. C. Wright, “Reforms in the Bengal Salt Monopoly, 1786-95”, Studies in Romanticism 1, no. 3 (1962), p.151

6. Gervase Markam, Markhams farwell to husbandry or, The inriching of all sorts of barren and sterill grounds in our kingdome (1620), p.22

March 2, 2024

The Hindenburg Disaster – Dining on the Zeppelin

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Nov 28, 2023Decadent vanilla rice pudding with poached pears, chocolate sauce, and candied fruit

City/Region: France

Time Period: 1903Everything about this dish exudes fanciness, and it comes as no surprise. A ride across the Atlantic on the Hindenburg cost around $9,000 in today’s money, and the whole experience was meant to be luxurious. The head chef on the Hindenburg, Xaver Maier, had worked at the Ritz Hotel in Paris, which was still cooking from the recipes of Auguste Escoffier.

The Escoffier recipe for pears condé seems simple enough, until you realize he references about 5 other recipes in total in order to make the dish. It’s a lot of work, but it’s so good. The rice pudding has such an intense vanilla flavor that really elevates it and is the perfect base for the poached pears. Don’t get too much of the rich chocolate sauce or it will overwhelm the other flavors.

Really you could make just the rice pudding and have that be a fancy dessert all on its own if you don’t want to go to all the fuss.

Poires Condé:

Very small pears which are carefully peeled and shaped are most suitable for this preparation. Those of medium size should be cut in half. Cook them in vanilla-flavored syrup then proceed as for Abricots Condé, recipe 4510.

Abricots Condé:

On a round dish prepare a border of vanilla-flavored Prepared Rice for sweet dishes (recipe 4470)— Auguste Escoffier, 1903

ambience

ambience