Back in Early Modern England, enclosure led to a massive over-supply of labor. The urge to explore and colonize was driven, to an unknowable but certainly large extent, by the effort to find something for all those excess people to DO. The fact that they’d take on the brutal terms of indenture in the New World tells you all you need to know about how bad that labor over-supply made life back home. The same with “industrial innovation”. The first Industrial Revolution never lacked for workers, and indeed, Marxism appealed back in its day because the so-called “Iron Law of Wages” seemed to apply — given that there were always more workers than jobs …

The great thing about industrial work, though, is that you don’t have to be particularly bright to do it. There’s always going to be a fraction of the population that fails the IQ test, no matter how low you set the bar, but in the early Industrial Revolution that bar was pretty low indeed. So much so, in fact, that pretty soon places like America were experiencing drastic labor shortages, and there’s your history of 19th century immigration. The problem, though, isn’t the low IQ guys. It’s the high-IQ guys whose high IQs don’t line up with remunerative skills.

My academic colleagues were a great example, which is why they were all Marxists. I make fun of their stupidity all the time, but the truth is, they’re most of them bright enough, IQ-wise. Not geniuses by any means, but let’s say 120 IQ on average. Alas, as we all know, 120-with-verbal-dexterity is a very different thing from 120-and-good-with-a-slide-rule. Academics are the former, and any society that wants to remain stable HAS to find something for those people to do. Trust me on this: You do not want to be the obviously smartest guy in the room when everyone else in the room is, say, a plumber. This is no knock on plumbers, who by and large are cool guys, but it IS a knock on the high-IQ guy’s ego. Yeah, maybe I can write you a mean sonnet, or a nifty essay on the problems of labor over-supply in 16th century England, but those guys build stuff. And they get paid.

Those guys — the non-STEM smart guys — used to go into academia, and that used to be enough. Alas, soon enough we had an oversupply of them, too, which is why academia soon became the academic-industrial complex. 90% of what goes on at a modern university is just make-work. It’s either bullshit nobody needs, like “education” majors, or it’s basically just degrees in “activism”. It’s like Say’s Law for retards — supply creates its own demand, in this case subsidized by a trillion-dollar student loan industry. Better, much better, that it should all be plowed under, and the fields salted.

Any society digging itself out of the rubble of the future should always remember: No overproduction of elites!

Severian, “The Academic-Industrial Complex”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-05-30.

November 26, 2023

QotD: From Industrial Revolution labour surplus to modern era academic surplus

November 22, 2023

Another look at the “Great Divergence”

The latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf features Patrick Wyman’s The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World:

This is a weird Substack featuring an eclectic selection of books, but one of our recurring interests is the Great Divergence: why and how did the otherwise perfectly normal people living in the northwestern corner of Eurasia managed to become overwhelmingly wealthier and more powerful than any other group in human history? We’ve covered a few theories about what’s behind it — not marrying your cousins, coal, the analytic mindset (twice) — but there are lots of others we’ve never touched, including geographic and thus political fragmentation, proximity to the New World, and even the Black Death. So this is also a book about the Great Divergence, but unlike many of the others it doesn’t offer One Weird Trick to explain things. Instead, Wyman approaches the period between 1490 and 1530 through nine people, each of whom exemplifies one of the many shifts in European society, and so paints a portrait of a changing world.

Of course, he does point to a common thread woven through many of the changes: culture. Or, more specifically, the institutions1 surrounding money and credit that Europeans had spent the last few hundred years developing. But these weren’t themselves dispositive: after all, lots of people in lots of place at lots of times have been able to mobilize capital, and most of them don’t produce graphs that look like this. Really, the secret ingredient was — as Harold Macmillan said of the greatest challenge to his government — “events, dear boy, events”.2 Europe between 1490 to 1530 saw an unusually large number of innovations and opportunities for large-scale, capital-intensive undertakings, and already had the economic institutions in place to take advantage of them. One disruption fed on the next in a mutually-reinforcing process of social, political, religious, economic, and technological change that (Wyman argues) set Europe on the path towards global dominance.

Some of Wyman’s characters — Columbus, Martin Luther, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V — are intensely familiar, but he presents them with verve, as interested in giving you a feel for the individual and their world as in conveying biographical detail. (This is an underrated goal in the writing of history, but really invaluable; the “Cross Section: View from …” chapters were always my favorite part of Jacques Barzun’s idiosyncratic doorstopper From Dawn to Decadence.) This is particularly welcome when it comes to the chapters featuring some lesser-known figures: you may have heard of Jakob Fugger, but unless you’re a Wimsey-level fan of incunabula you’re probably unfamiliar with Aldus Manutius. One-handed man-at-arms Götz von Berlichingen becomes our lens for the chapter about the Military Revolution not because he played a particularly significant role but because he wrote a memoir, and small-time English wool merchant John Heritage is notable pretty much solely because his account book happened to survive into the present. But even with the stories “everyone knows”, Wyman takes several large steps back in order to contextualize that common knowledge: for example, were you aware that while before 1492 Columbus didn’t take any particularly unusual voyages, he did take an unparalleled number and variety of them, making him one of the best-travelled Atlantic sailors of his day? Did you know that Isabella’s inheritance of the Castilian throne was far from certain?3

As the book continues, Wyman can reference the cultural and technological shifts he described in earlier chapters. For instance, much of the Fuggers’ wealth came in the form of silver from deep new mines in the Tyrol. Building the mines required substantial capital — for their new, deeper tunnels and the expensive pumps to drain them, as well as for the furnaces and workshops to separate the copper from the silver via the relatively inefficient liquation process — and while everyone knew all along that the metals were there, it took the combination of a continent-wide bullion shortage and a rising demand for copper to cast bronze cannon (look back to the chapters on state formation and the military!) to make it worth anyone’s while to get them out. But it wasn’t only the Fuggers who made their money in these new mines: the money for Martin Luther’s education came from his father’s small-scale copper mining concern in eastern Germany. Grammar school in his hometown, a parish school nearby, and then four years at university cost Luther pater enough that he couldn’t follow it up for his younger sons (and from his point of view the was probably squandered when Martin became a monk instead of the intended lawyer who would be an asset in the frequent mining disputes), but such an education for even one son would have been out of reach if not for the printed texts on grammar, philosophy and law that made it all far more affordable.

Of course, the relationship between Luther and printing goes both ways. While Luther’s very existence as an educated man was enabled by the printing press, it was the intellectual and religious ferment he would kick off that made printing work.

1. Wyman glosses the term as “a shared understanding of the rules of a particular game … the systems, beliefs, norms and organizations that drive people to behave in particular way”, but it’s more or less what I’ve elsewhere called bundles of social technologies.

2. Apparently he may not have said this, but he should have so print the legend.

3. Isabella’s opponent, her half-niece Joanna, was married to King Afonso V of Portugal, so perhaps some degree of Iberian unification might still have followed. On the other hand, Afonso already had an adult son (King João II, widely admired as “the Perfect Prince” — Isabella always referred to him simply as el Hombre, “the Man”) who would have had no personal claim to Castile. Joanna and Afonso’s marriage was annulled on the perfectly true grounds of consanguinity — he was her uncle — after they lost the war, so they never had children, but if she had won perhaps João (who died without legitimate issue) could have been succeeded by a much younger half-Castilian half-brother. Certainly an Isabella relegated to Queen-Consort of Aragon would still have been a force to be reckoned with, but losing the knock-on effects of her reign (Columbus, Granada, the fate of the Sephardim, not to mention the eventual unification of most of Europe under Ferdinand and Isabella’s Habsburg grandson) makes all this a pretty good setup for an alternate history!

Even more fun: before she married Ferdinand of Aragon, there was discussion of Isabella’s betrothal to Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Yeah, that one.

October 20, 2023

Zulu Kingdom’s Last Stand – The Anglo-Zulu War 1879

Real Time History

Published 18 Oct 2023The Anglo-Zulu War in 1879 is one of the most well known colonial wars of the British Empire. And while the British ultimately won and annexed the Zulu Kingdom, at the Battle of Isandlwana they suffered one of their worst defeats.

(more…)

October 5, 2023

From Hilaire Belloc’s sailboat to your nearest international airport terminal

The most recent review at Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf considers Hilaire Belloc’s The Cruise of the “Nona”:

Late in the May of 1925, around midnight, Hilaire Belloc climbed into a tiny boat and put out to sea so that he would have some time to think. The sea gives ample time to think, especially if like Belloc you disdain the use of a motor. Some wag once jested that sailing is like being at war: long stretches of boredom punctuated by moments of abject terror. I suppose in some sense that’s correct, but give me the boredom of the sailboat any day over the boredom of the trench, the boredom of the cubicle, the boredom of endless doomscrolling.

Sailing is productive boredom, and seems unusually well calibrated for causing the mind to wander in interesting or delightful or just plain ridiculous directions. Maybe it’s the stimulating effects of the wind in your face and the smell of salt in the air, or maybe it’s the weird altered state of consciousness that comes from staring at the ocean. I think it’s because sailing is the human condition in miniature. It places you perfectly-balanced on a knife’s edge between agency and helplessness, and in so doing it both spurs the mind to activity and gives it space to relax and reflect.1

[…]

Anybody who’s travelled extensively in the third world has seen the modern version of this. There’s nothing intrinsic to being a reformer or a liberalizer that makes you an agent of American power, and yet … there’s a better than even chance that you are. After a while these people all blend together — the idealistic students, the LGBT activists, the NGO staffers, the embassy employees recruited from amongst the locals. They come from a hundred nations, from every conceivable race and religion, and yet something invisibly and inexorably molds them all into the same shape, like iron filings lining themselves up in the presence of a powerful magnet.

Soon they have American souls, and divided loyalties to match. The local regime panics and views them as an internal enemy, which only furthers their alienation from their motherland and their flight into the bosom of Global America. Most empires rule primarily though influence, not coercion, and this class of people is one of America’s most powerful weapons for maintaining and extending its hegemony.

A related phenomenon is the awful sameness that is slowly taking over the whole world. Perhaps your cruise ship docks at a dozen ports over the course of its journey, and every one of them looks exactly the same — the same tiki bar with the same sign, the same shops selling the same ornamental kitsch probably all made in the same factory. You aren’t visiting a place, you’re visiting a psychic manifestation of the Buffetverse, another outpost of Margaritaville, a Potemkin seaport with frozen daiquiris. You all know what I’m talking about. We make fun of it all the time, because cruise ships are for chuds. But it doesn’t just happen with cruise ships.

The cancer usually starts in an international airport. Form follows function, so it’s superficially reasonable that every airport on earth should look and feel exactly the same. But the real reason is that it follows in the wake of the kinds of people who fly into those airports, praising the broadening effects of foreign travel whilst terraforming everything they touch until it resembles the “arts district” of a midsize American city, replete with distressed wood finishes, gravid with craft beers. Real foreignness would cause these people to recoil in shock, or to demand a peacekeeping intervention. It’s not unusual for the imperial functionary class to be parochial, but what’s surreal about ours is how they combine the blinkered innocence of a farm boy with an ideology of weary cosmopolitanism.

None of this was as far along when Belloc took his little cruise, but the seeds had been planted, and he could feel in his bones that something horrible lay across the horizon. So he fights it the only way he knows how — by noticing and celebrating everything distinctive and local and weird about every place he visits. No island is too small for him to mention by name and recall a ghost story or two associated with it. No village is too commonplace for him to remark on the habits, physiognomy, and vices of the people who live in it. It’s the same spirit as that which animates Chesterton’s essay on cheese, but applied to a hundred hamlets and fishing ports, a paean to the regional diversity and distinctiveness that was already slipping away.

1. Oh hey, it’s the focused-mode and diffuse-mode of cognition! The best way to think deeply about anything is to toggle between them.

October 2, 2023

Why France Lost Vietnam: The Battle of Dien Bien Phu

Real Time History

Published 29 Sept 2023After the French success in the Battle of Na San, the battle of Dien Bien Phu is supposed to defeat the Viet Minh once and for all. But instead the weeks-long siege becomes a symbol of the French defeat in Vietnam.

(more…)

September 16, 2023

France’s Vietnam War: Fighting Ho Chi Minh before the US

Real Time History

Published 15 Sept 2023After the Second World War multiple French colonies were pushing towards independence, among them Indochina. The Viet Minh movement under Ho Chi Minh was clashing with French aspirations to save their crumbling Empire.

(more…)

August 29, 2023

The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois “runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of ‘decolonise'”

In Spiked, Brendan O’Neill finds himself surprised at the inclusion of a very unusual book on a list demanded by those pushing for “decolonization” of university curricula:

W.E.B. Du Bois by James E. Purdy, 1907, gelatin silver print, from the National Portrait Gallery which has explicitly released this digital image under the CC0 license.

Wikimedia Commons.

“Decolonise the curriculum” is a movement that wants university courses to focus less on dead white European males and more on writers of colour. Its argument is that black students need texts that speak directly to them. They need books by authors who look like them. They need books about experiences and ideas they can more readily relate to than they can the stuff written about in “high white culture”. Black students must be able to recognise themselves in what they study, we’re told, or else they’ll feel cheated and demeaned.

I was surprised to find that one of the leading decolonise movements, at the University of Edinburgh, was arguing for WEB Du Bois’ 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk, to be included on the English curriculum. The activists said it was unreasonable to expect black students to engage with so many white authors. They also need to engage with people like Du Bois, in whose work they might “recognise themselves”. I was surprised, not because I think The Souls of Black Folk shouldn’t be on more university courses – absolutely it should. No, it’s because The Souls of Black Folk runs so fantastically counter to the entire ideology of “decolonise”. It made me wonder if these activists have even read it. Du Bois’ book contains some of the finest arguments you will ever read against the idea that high culture is a white thing that others cannot connect with.

One of my favourite passages in the book, from the chapter on what kind of education black men are fit for, touches on this very question. Here Du Bois makes his critique of those in his own time who were arguing that blacks only require basic education and industrial training. He describes his own experience of higher learning, writing:

I sit with Shakespeare and he winces not. Across the colour line I move arm in arm with Balzac and Dumas … From out the caves of evening that swing between the strong-limbed earth and the tracery of the stars, I summon Aristotle and Aurelius and they come all graciously with no scorn or condescension.

That passage, Du Bois’ moving belief that Shakespeare does not wince at him, captures a central thread of his writing: universalism. Du Bois agitates against accommodating to segregation or low expectations, and argues for the rights of “black folk” to assimilate into the spoils of civilisation; to become, as he puts it, “co-workers in the kingdom of culture”. To those in the late 1800s and early 1900s who argued that black people needed a targeted form of culture, one specific to their needs and capacities, Du Bois said: “We daily hear that an education that encourages aspiration, that sets the loftiest of ideals and seeks as an end culture and character rather than breadwinning, is the privilege of white men, and the danger and delusion of black men.”

Du Bois insisted that it is only through assimilation into the “kingdom of culture” that self-knowledge and self-improvement can truly occur. As he wrote: “Wed with Truth, I dwell above the veil.” The veil he’s referring to is the veil of colour, the one that separated blacks from whites in post-slavery America. For Du Bois, that veil was best lifted via assimilation into the American republic’s political universe and its realm of culture.

Du Bois’ critique of the notion that high culture was for white men, and would prove mystifying to black men, has sadly been superseded by an “anti-racism” with an entirely different outlook. Now, the supposedly radical stance is to believe that high culture is disorientating for black people, and possibly even damaging to their self-esteem, and therefore they require something more targeted. In short, they need release from the kingdom of culture. That, in essence, is what the decolonise movement desires: the “liberation” of non-white peoples from the cultural gains of Western civilisation. Behold the crisis of universalist belief.

August 21, 2023

Cunk on America – Historian Reacts

Vlogging Through History

Published 9 May 2023

(more…)

August 12, 2023

Churchill and India

Andreas Koureas posted an extremely long thread on Twitter, outlining the complex situation he and his government faced during the Bengal Famine of 1943, along with more biographical details of Churchill’s views of India as a whole (edits and reformats as needed):

The most misunderstood part of Sir Winston Churchill’s life is his relationship with India. He neither hated Indians nor did he cause/contribute to the Bengal Famine. After reading through thousands of pages of primary sources, here’s what really happened.

A thread 🧵

I’ve covered this topic before, but in a recent poll my followers wanted a more in-depth thread. Sources are cited at the end. I’m also currently co-authoring a paper for a peer reviewed journal on the subject of the Bengal Famine, which should hopefully be out later this year.

I’ll first address the Bengal Famine (as that is the most serious accusation) and then Churchill’s general views on India. It goes without saying that there will be political activists who will completely ignore what I have to say, as well as the primary sources I’ll cite. I have no doubt, that just like in the past, there will be those who accuse me of only using “British sources”.

This is not true. I have primary sources written by Indians as well as papers by Indian academics.

Moreover, I have no doubt that such activists will, choose to “cite” the ahistorical journalistic articles from The Guardian or conspiratorial books like Churchill’s Secret War by Mukerjee — a debunked book that ignores most of what I’m about to write about, and is really what sparked the conspiracy of Churchill and the Bengal Famine. For everyone else, I hope you find this thread useful.

(more…)

August 8, 2023

QotD: The British imperial educational “system”

The history of “education”, of the university system, whatever you want to call it, is long and complicated and fascinating, but not really germane. Like all human institutions, “educational” ones grew organically around what were originally very different foundations, the way coral reefs form around shipwrecks. Oversimplifying for clarity: back in the day, “schools” were supposed to handle education […] while universities were for training. That being the case, very few who attended universities emerged with degrees — a man got what training he needed for his future career, and unless that future career was “senior churchman”, the full Bachelor of Arts route was pretty much pointless.

(At the risk of straying too far afield, let’s briefly note that “senior churchman” was a common, indeed almost traditional, career path for the spare sons of the aristocracy. Well into the 18th century, every titled parent’s goal was “an heir and a spare”, with the heir destined for the title and castle and the spare earmarked for the church … but not, of course, as some humble parish priest. It was pretty common for bishops or abbots, and sometimes even cardinals, to be ordained on the day they took over their bishoprics. See, for example, Cesare Borgia. Meanwhile the illiterate, superstitious, brutish parish priest was a figure of satire throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. A guy like Thomas Wolsey was hated, in no small part, precisely because he was a commoner who leveraged his formal education into a senior church gig, taking a bunch of plum positions away from the aristocracy’s spare sons in the process).

That being the case — that schools were for education, universities for training — the fascinating spectacle of some 18 year old fop fresh out of Eton being sent to govern the Punjab makes a lot more sense. His character, formed by his education (in our sense), was considered sufficient; he’d pick up such technical training as he needed on the job … or employ trained technicians to do it for him. So too, of course, with the army, and the more you know about the British Army before the 20th century, the more you’re amazed that they managed to win anything, much less an empire — the heir’s spare’s spare traditionally went into the army, buying his commission outright, which meant that quite senior commands could, and often did, go to snotnosed teenagers who didn’t know their left flank from their right.

Alas, governments back in the days were severely under-bureaucratized, meaning that the aristocracy lacked sufficient spares to fill all the technician roles the heirs required in a rapidly urbanizing, globalizing world… which meant that talented commoners had to be employed to fill the gaps. See e.g. Wolsey, above. The problem with that, though, is that you can’t have some dirty-arsed commoner, however skilled, wiping his nose on his sleeve while in the presence of His Lordship, so universities took on a socializing function. And so (again, grossly oversimplifying for clarity) the “bachelor of arts” was born, meaning “a technician with the social savvy to work closely with his betters”. A good example is Thomas Hobbes, whose official job title in the Earl of Devonshire’s household was “tutor”, but whose function was basically “intellectual technician” — he was a kind of man-of-all-work for anything white collar …

At that point, if there had been a “system” of any kind, what the system’s designers should’ve done is set up finishing schools. The “universities” of Oxford, Cambridge, etc. are made up of various “colleges” anyway, each with their own rules and traditions and house colors and all that Harry Potter shit. Their Lordships should’ve gotten together and endowed another college for the sole purpose of knocking manners into ambitious commoners on the make (Wolsey might actually have had something like this in mind with Cardinal College … alas).

But they didn’t, and so the professors at the traditional colleges were forced into a role for which they were not designed, and unqualified. That tends to happen a lot — have you noticed? It actually happened to them twice, once with the need for technicians-with-manners became apparent, and then again when the realization dawned — as it did by the 1700s, if not earlier — that some subjects, like chemistry, require not just technicians and technician-trainers, but researchers. Hard to blame the “system” for this, since of course there is no “system”, but also because such a thing would be ruinously expensive.

Hence by the time an actual system came into being — in Prussia, around 1800 — the professors awkwardly inhabited the three roles we started with. The Professor of Chemistry, say, was supposed to conduct research while training technicians-with-manners. As with the pre-machinegun British army, the astounding thing is that they managed to pull it off at all, much less to such consistently high quality. They were real men back then …

Severian, “Education Reform”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-11-17.

July 15, 2023

The French Intifada

Ed West on the origins of the rising violence in French towns and cities:

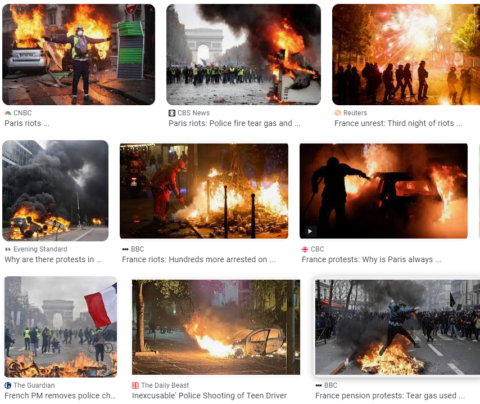

I ran an image search for “Paris rioting” and there was a plentiful supply of fiery, eye-catching photos. Not all of these are from the most recent outbreak of violence, but they are certainly representative of how the legacy media is covering the situation.

The recent violence in Paris and elsewhere, which saw attempts to ram the home of a mayor, once again highlighted the trouble the country has with integration. But the French police union describing themselves as being “at war with vermin” illustrated the different mindset to the English-speaking world, and the far more belligerent approach to the problems of diversity.

Like Britain, the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden, France has had difficulties assimilating the children of immigrants from beyond Europe, yet its recent history has proved especially violent and troubled. Britain has jihadi terrorism – 2017 was especially grim – but it has never reached such intensity. Today, as over 130,000 police officers stand guard to protect the Republic on the day of its celebration, it is worth considering the journey that brought it to such a state.

Analysts have often compared Britain’s state multiculturalism with France’s system of laïcité, which tends to downplay the existence of “communities” even to the point of not taking demographic statistics. Although neither country’s approach has entirely been a success, France’s refusal to recognise immigrants as anything but French has often been blamed for the widespread sense of alienation.

Others point to the housing system, which tends towards concentrations of North and West Africans in suburban banlieues, or the less laissez-faire economic policy which results in higher unemployment (in exchange for better social security).

While they no doubt play a part, the biggest single difference is history, as Andrew Hussey recounted back in 2014 in The French Intifada, in particular France’s history with North Africa. To put it in British terms, imagine that Britain’s rule in Pakistan had involved not a small number of administrators and soldiers but instead hundreds of thousands of British settlers arriving in the country, many with the intention of making it a “new America” (i.e. driving the natives out).

That Britain had declared Pakistan an integral part of the country, and that, rather than scarpering in indecent haste when the empire began to disintegrate, Britain had dug in to preserve its rule in a sadistic war of independence, one in which natives and white settlers committed countless atrocities against each other.

And that this violence had spilled into Britain with assassination attempts and terrorism, by both sides, destabilising the country to the point where there was talk of a coup. And that this was happening just as large-scale immigration to the colonial power was taking place.

Britain experienced nothing like as much violence in the dying days of empire, and indeed the only real comparison with our history was the moment when there was almost all-out conflict between Britain’s Protestant and Irish Catholic populations before the First World War.

If French politicians so casually talk of “civil war” between its right wing and the Algerian-descended population, it is because it has already played out this conflict before – one that was never healed, and so invites a sequel.

July 6, 2023

“Too many complaints? That’s racism. Too few complaints? Well, that’s racism, too.”

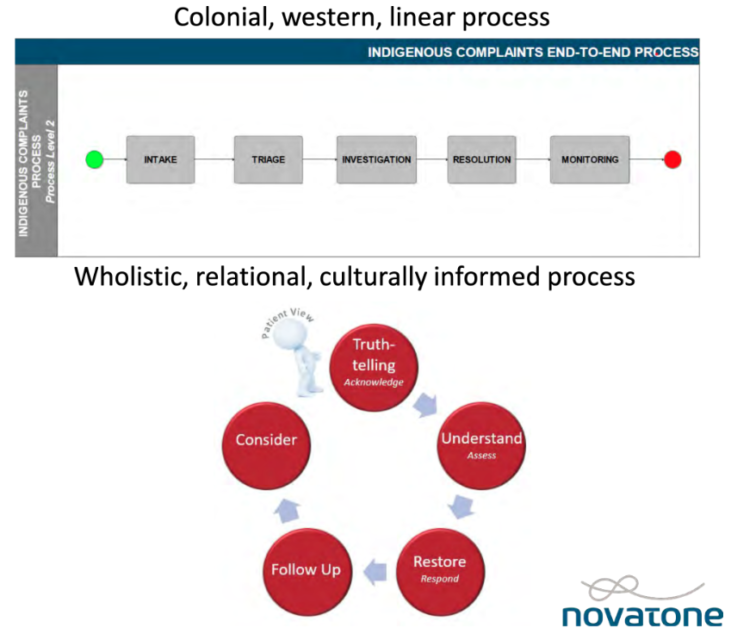

Amy Eileen Hamm reports on how the British Columbia College of Nurses and Midwives (BCCNM) acted on its concern that not enough complaints against their members were being lodged by First Nations people:

As regular readers of Quillette will know, many Canadian institutions have fervently adopted the cause of “decolonization” — a vaguely defined term that one university describes as the dismantling of “assumed Euro-western disciplinary constructs and traditions”. This can mean anything from abolishing musical scales (which “perpetuate and solidify the hegemony of [the] Euro-American repertoire”); to reimagining our scientific understanding of sunlight, so as to correct “the reproduction of colonialism” that has infected “physics and higher physics education”; to assailing the gender binary through a “decolonizing act of resistance”.

That’s the theory, anyway. In practice, institutional efforts at “decolonization” generally translate into affirmative-action hiring programs and policies to mandate symbolic (generally empty) gestures such as land acknowledgements. They’ve also created a cash cow for “specialist” administrators and third-party consultants in what is now known as the “equity, diversity, inclusion, and decolonization” sector. The premise is that decolonization is so difficult and complex that it can only be overseen by said (highly paid) professionals.

My own professional sector, nursing, provides a useful case study. In British Columbia, where I live and work, nurses are licenced by the British Columbia College of Nurses & Midwives (BCCNM), whose offices are located “on unceded Coast Salish territory, represented today by the Musquea?m, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.” In other words, Vancouver.

If a patient feels that he or she has experienced “incompetent, unethical, or impaired nursing or midwifery practice”, he or she can complain to the BCCNM through its complaints portal. It’s not a complicated process. You send an email describing what the nurse allegedly did, when the incident occurred, and whether there were any witnesses. If you’ve already complained to someone else, you’re supposed to note that as well, along with your suggestions for resolving the complaint. That’s it.

But apparently, this process is just too onerous — and even dangerous — for Indigenous people. And so the BCCNM has paid C$97,000 to a self-described “boutique business process management firm” called Novatone, which has duly produced a lengthy report on how to “make the BCCNM complaints process safer for Indigenous Peoples.” The same title — mantra might be a better word — appears at the top of all 50 pages: Looking Back to Look Forward: How Indigenous ways of being, knowing, and doing must inform the BCCNM feedback process and reflect the principles of cultural safety, cultural humility, and anti-racism.

(For the benefit of those outside Canada, the mystical-sounding phrase, “ways of knowing”, along with its “being” and “doing” variants, has now entered the official idiom as a means to signify the unfalsifiable shaman-like intuitions that supposedly guide the consciousness of Indigenous people throughout every facet of their existence — including, apparently, complaining about the care they receive from nurses.)

July 4, 2023

QotD: The (arguments over the) founding of America

You could of course say that the ideals of universal equality and individual liberty in the Declaration of Independence were belied and contradicted in 1776 by the unconscionable fact of widespread slavery, but that’s very different than saying that the ideals themselves were false. (They were, in fact, the most revolutionary leap forward for human freedom in history.) You could say the ideals, though admirable and true, were not realized fully in fact at the time, and that it took centuries and an insanely bloody civil war to bring about their fruition. But that would be conventional wisdom — or simply the central theme of President Barack Obama’s vision of the arc of justice in the unfolding of the United States.

No, in its ambitious and often excellent 1619 Project, the New York Times wants to do more than that. So it insists that the very ideals were false from the get-go — and tells us this before anything else. Even though those ideals eventually led to the emancipation of slaves and the slow, uneven and incomplete attempt to realize racial equality over the succeeding centuries, they were still “false when they were written”. America was not founded in defense of liberty and equality against monarchy, while hypocritically ignoring the massive question of slavery. It was founded in defense of slavery and white supremacy, which was masked by highfalutin’ rhetoric about universal freedom. That’s the subtext of the entire project, and often, also, the actual text.

Hence the replacing of 1776 (or even 1620 when the pilgrims first showed up) with 1619 as the “true” founding. “True” is a strong word. 1776, the authors imply, is a smoke-screen to distract you from the overwhelming reality of white supremacy as America’s “true” identity. “We may never have revolted against Britain if the founders had not understood that slavery empowered them to do so; nor if they had not believed that independence was required in order to ensure that slavery would continue. It is not incidental that 10 of this nation’s first 12 presidents were enslavers, and some might argue that this nation was founded not as a democracy but as a slavocracy,” Hannah-Jones writes. That’s a nice little displacement there: “some might argue”. In fact, Nikole Hannah-Jones is arguing it, almost every essay in the project assumes it — and the New York Times is emphatically and institutionally endorsing it.

Hence the insistence that everything about America today is related to that same slavocracy — biased medicine, brutal economics, confounding traffic, destructive financial crises, the 2016 election, and even our expanding waistlines! Am I exaggerating? The NYT editorializes: “No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed … it is finally time to tell our story truthfully”. Finally! All previous accounts of American history have essentially been white lies, the NYT tells us, literally and figuratively. All that rhetoric about liberty, progress, prosperity, toleration was a distraction in order to perpetrate those lies, and make white people feel better about themselves.

Andrew Sullivan, “The New York Times Has Abandoned Liberalism for Activism”, New York, 2019-09-13.

May 12, 2023

Dispatch from the front lines of the Imperial History Wars

In Quillette, Nigel Biggar recounts how he was conscripted into the Imperial History Wars:

It was December 2017, and my wife and I were at Heathrow airport, waiting to board a flight to Germany. Just before setting off for the departure gate, I could not resist checking my email one last time. My attention sharpened when I saw a message in my inbox from the University of Oxford’s Public Affairs Directorate. What I found was a notification that my “Ethics and Empire” project, organized under the auspices of Oxford’s McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics & Public Life, had become the target of an online denunciation by a group of students; followed by reassurance from the university that it had risen to defend my right to run such a thing.

So began a weeks-long public row that raged over the project, which had “gathered colleagues from Classics, Oriental Studies, History, Political Thought, and Theology in a series of annual workshops to measure apologias and critiques of empire against historical data from antiquity to modernity across the globe.” Four days after I flew, the eminent imperial historian who had conceived the project with me abruptly resigned. Within a week of the first online denunciation, two further ones appeared, this time manned by professional academics, the first comprising 58 colleagues at Oxford, the second, about 200 academics from around the world. For over a fortnight, my name was in the press every day.

What had I done to deserve all this unexpected attention? Three things. In late 2015 and early 2016, I had offered a partial defence of the late-19th-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes during the Rhodes Must Fall campaign in Oxford. Then, in late November 2017, I published a column in the Times, in which I referred approvingly to Bruce Gilley’s controversial article “The Case for Colonialism”, and argued that the British (along with Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders) have reason to feel pride as well as shame about their imperial past. Note: pride, as well as shame. And a few days later, third, I finally got around to publishing an online account of the “Ethics and Empire” project, whose first conference had in fact been held the previous July.

Contrary to what the critics seemed to think, the Ethics and Empire project is not designed to defend the British Empire, or even empire in general. Rather, it aims to select and analyse evaluations of empire from ancient China to the modern period, in order to understand and reflect on the ethical terms in which empires have been viewed historically. A classic instance of such an evaluation is St Augustine’s The City of God, the early-fifth-century AD defence of Christianity, which involves a generally critical reading of the Roman Empire. Nonetheless, Ethics and Empire was conceived with awareness that the imperial form of political organisation was common across the world and throughout history until 1945; and so does not assume that empire is always and everywhere wicked; and does assume that the history of empires should inform — positively, as well as negatively — the foreign policy of Western states today.

The territories that were at one time or another part of the British Empire. The United Kingdom and its accompanying British Overseas Territories are underlined in red.

Composed by “The Red Hat of Pat Ferrick” via Wikimedia Commons.Thus did I stumble, blindly, into the Imperial History Wars. Had I been a professional historian, I would have known what to expect, but being a mere ethicist, I did not. Still, naivety has its advantages, bringing fresh eyes to see sharply what weary ones have learned to live with.

One surprising thing I have seen is that many of my critics are really not interested in the complicated, morally ambiguous truth about the past. For example, in the autumn of 2015, some students began to agitate to have an obscure statue of Cecil Rhodes removed from its plinth overlooking Oxford’s High Street. The case against Rhodes was that he was South Africa’s equivalent of Hitler, and the supporting evidence was encapsulated in this damning statement: “I prefer land to n—ers … the natives are like children. They are just emerging from barbarism … one should kill as many n—ers as possible.” As it turns out, however, initial research discovered that the Rhodes Must Fall campaigners had lifted this quotation verbatim from a book review by Adekeye Adebajo, a former Rhodes Scholar who is now director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation at the University of Johannesburg. Further digging revealed that the “quotation” was, in fact, made up from three different elements drawn from three different sources. The first had been lifted from a novel. The other two had been misleadingly torn out of their proper contexts. And part of the third appears to have been made up.

There is no doubt that the real Rhodes was a moral mixture, but he was no Hitler. Far from being racist, he showed consistent sympathy for individual black Africans throughout his life. And in an 1894 speech, he made plain his view: “I do not believe that they are different from ourselves.” Nor did he attempt genocide against the southern African Ndebele people in 1896 — as might be suggested by the fact that the Ndebele tended his grave from 1902 for decades. And he had nothing at all to do with General Kitchener’s concentration camps during the Second Boer War of 1899–1902 (which themselves had nothing morally in common with Auschwitz). Moreover, Rhodes did support a franchise in Cape Colony that gave black Africans the vote on the same terms as whites; he helped to finance a black African newspaper; and he established his famous scholarship scheme, which was explicitly colour-blind and whose first black (American) beneficiary was selected within five years of his death.

May 7, 2023

Africa after colonialism

Hannes Wessels on the plight of so many African nations once the various colonial powers were off the scene and they were at least formally independent:

If you have a heart in Africa it’s probably not a good idea to read Martin Meredith’s State of Africa because if you do, it will, in all likelihood, break it. In it, he covers, in gory detail, what has happened on the continent in the postcolonial era, and while it’s riveting, it is also deeply disturbing.

[…] “by the end of the 1980s not a single African head of state in three decades had allowed himself to be voted out of office. Of some 150 heads of state who had trodden the African stage, only six had voluntarily relinquished power”?

Or the fact that, in the Congo alone, in 1964, over a million people, virtually all civilians, died in sectarian strife. Nobody knows precisely how many more millions have died in the benighted country since. Or that Mobutu Sese Seko, prior to coming to power, had $6 in his bank account. By 1987 a team of editors and reporters from Fortune magazine disclosed that he was one of the richest men in the world at an estimated $5 billion.

Or the fact that Jean Bedel Bokassa “combined not only extreme greed and personal violence … unsurpassed by any other African leader. His excesses included seventeen wives, a score of mistresses and an official brood of 55 children … [He] also gained a reputation for cannibalism. Political prisoners … were routinely tortured on Bokassa’s orders, their cries clearly audible to nearby residents”. In an effort to compare himself to Napoleon, he declared himself an emperor and spent a large chunk of the national budget on his coronation while his people suffered and starved.

Or the fact that Uganda’s Idi Amin, in a bid to crush political opposition, ordered the gruesome deaths of thousands of alleged opponents at the hands of his “death squads”. “The Chief Justice was dragged away from the High Court never to be seen again. The university’s Vice Chancellor disappeared. The bullet-riddled body of an Anglican Archbishop, still in ecclesiastical robes, was dumped at the mortuary of a Kampala hospital. One of Amin’s former wives was found with her limbs dismembered in the boot of a car. Amin was widely believed to perform blood rituals over the bodies of his victims.” He was heard on several occasions boasting about his penchant for eating human flesh.

Or the fact that foreign researcher Robert Klintberg reported on oil-rich Equatorial Guinea as being “a land of fear and devastation no better than a concentration camp — the ‘cottage industry Dachau of Africa’.” Under Macias Nguema, more than half of the population was either killed or fled into exile. Finally deposed by his nephew, Obiang was indicted for the murder of 80,000 people. The plunder continued.

Or that in Nigeria, between 1988 and 1993, an official report estimated $12.2 billion was “diverted” from the fiscus. In 1990, the United Nations concluded that Nigeria had one of the worst records for human deprivation of any country in the developing world.

These are only a smattering of an almost endless litany of entirely avoidable man-made catastrophes that have blighted Africa since the imperial exit. One is left wondering if there is any precedent in history for such calamitous misrule that has led to the early, often violent deaths of millions, and delivered unspeakable misery to hundreds of millions more, which is where we are today.

Having read the book, I’m left pondering the fact that Cecil Rhodes, a colonial colossus, looms large in contemporary history as one of the great villains of the last century, better known for his alleged malfeasance than any of the abovementioned leaders. But as far as I know, Rhodes never stole from anyone and never killed anyone, and he certainly didn’t eat anyone. I know he did use his money and military muscle to stop slavery and intertribal slaughter. And I know he plowed most of his fortune into building roads, railways, educational facilities, and other infrastructure needed to transform a wilderness into a developed country. It looks to me like his generosity of spirit is reflected in the Rhodes scholarships he provided for, aimed at nurturing the talents of a select few from across the racial divides in a bid to make the world he was leaving a better place.