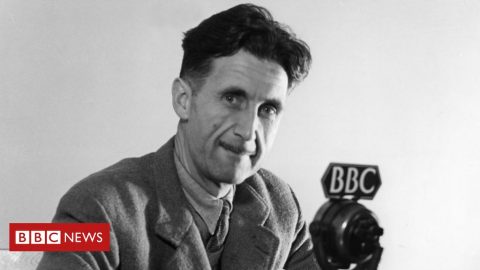

In The Daily Sceptic, Paul Sutton recounts a recent discussion with some Oxford graduate students where the topic of George Orwell came up:

The students maintained that the important thing is quality of writing but, paradoxically, this can only be judged by a strict contemporary “evaluation” of any Right-wing or outdated views. Inevitably, this contextualisation then reveals that said writers are “problematic” and “not as good as XYZ” – usually some figure who fits their sensibilities, and coincidentally one who’s almost always female – or at least better suited to the diversity required by these commissars.

So far, so well known and wearily familiar. The absolute impossibility of literature under such a mindset – one enthusiastically endorsed by graduate students who professed to live for literature – is utterly depressing. We’re in effect dealing with its cancellation.

I made a perfunctory effort in observing their complete inconsistency, but things got more interesting when Orwell was discussed. Of course, Orwell famously wrote against their stand, not least in his brilliant defence of Kipling’s literary merit and his refusal to allow orthodoxy to dictate his aesthetic preferences, in “Benefit of Clergy“.

Unfortunately, Orwell’s stint in the Burmese Imperial Police made him a despicable figure to the students, little better than a Waffen SS or Gestapo officer. True, he’d belatedly retrieved himself by his “eventual writing” in the 1940s, but he’d spent many years performing the dirty work of the British Empire. His famous essay, “A Hanging“, showed him enthusiastically hands on at it.

I’d honestly never heard such a narrow and limited view, and was intrigued. As a preposterous misrepresentation, it needs little rebuttal. “A Hanging” is indeed a brilliantly disturbing account of an Indian murderer being hanged, a man who’d have been executed at that time in any country. The essay explores the deep unease Orwell felt about his role, so it’s a lie to claim it shows him uncritically doing his job, let alone revelling in his exertion of British authority.

Such an interpretation shows a shocking lack of understanding. As does the idea that Orwell only recanted any pro-Imperial views in the 1940s; his underrated Burmese Days was published in 1934 and he wrote extensively about his disgust for the job he did in the late 20s and 1930s. Of course, he didn’t only feel disgust, nor would he pretend that the British brought only misery and were unique as imperial exploiters.

What I’m most interested in is how an alternative Orwell was then offered up, a writer who’d accepted the British Empire was “problematic” yet offered a nice comforting view of how nice and comforting life can be – if you agree with the progressives, that is.Step forward Jan Morris and his trilogy Pax Britannica. Now, I haven’t read this non-fictional account of the British Empire but from background knowledge, it’s not in any way a replacement for Orwell or even remotely comparable. It’s an exhaustive historical work, not a personal creative one. But this trilogy was extolled by the students as what Orwell should have done when discussing empire. There was the implication that Orwell could now be – somewhat thankfully – ignored.

Bizarrely, the Englishman then introduced Joyce, first saying that the man was a lifelong sponger who’d have probably fleeced him, but as a writer was the very model of a pan-European, liberal and open to all cultures. Again, the grubby contradictions and sheer banality of such a perspective are eye-popping – from a DPhil student in perhaps the country’s finest university.

And I’ve a nagging feeling that Jan Morris – a famous case of gender realignment (he “transitioned” to female in 1972) – was picked for the “acceptable author” reasons. That’s the problem with “author context” vetting – as with “diversity hires”. Much as I’ve enjoyed Morris’s travel writing, especially Oxford, it’s staggering for this author to be proposed as some alternative to Orwell! Not only in terms of obvious lesser importance, but they’re not remotely comparable in terms of genre or aims. How could any serious reader – let alone one at a leading university – talk such gibberish?