The Royal Commission on the Operation of the Poor Laws, set up in 1832, was chaired by Charles Blomfield, Bishop of London. It numbered several other prominent churchmen among its members. The deliberations of this body led to the Poor Law Reform Act of 1834. This charming statute was based on the idea that the provision of poor relief must be made so torturous and degrading that only those suffering from extreme starvation and indigence would accept it. The sole form of assistance was to be within the context of workhouses, which were to be made as miserable and hellish as any prison. Any family unfortunate enough to have no choice but to fall back on the workhouse would be split up, as mixed-sex institutions would “undermine the good administration” of the workhouses, as the authorities euphemistically put it.

One of the law’s architects, Edwin Chadwick — a man who made Mr Gradgrind [Wiki] look like one of the Cheeryble brothers [Wiki] — infamously commented that it was vital that the inmates of workhouses should be given the coarsest food possible. William Cobbett, a leading opponent of the bill, gleefully seized on this, nicknaming the Whigs, who pushed the legislation hardest, the “Coarser Food Party”. The idea of all this — rooted in the principles of utilitarianism, political economy and Malthusianism — was, as future Archbishop of Canterbury John Bird Sumner put it, to encourage the labouring poor to do everything they could to avoid the “intemperance and want of prudent foresight” that creates poverty, the “punishment which the moral government of God inflicts in this world upon thoughtlessness and guilty extravagance”.

In the 1830s, these ideas were at the very vanguard of progressive thinking. They were promoted by the metropolitan liberal elite of the age, men such as James Mill, Jeremy Bentham and David Ricardo, the forward-thinking “Philosophic Radicals” who spewed out reforming and “improving” ideas through their famous organ The Westminster Review. Other contributors included happy-go-lucky eugenicist pioneer and social Darwinist Herbert Spencer, as well as Harriet Martineau, the sort of woman who would cheerfully have put her “enlightened benevolence” into practice by personally taste-testing workhouse food to ensure it was sufficiently coarse.

These ideas were gleefully leapt upon by a large swathe of the Church leadership, who endorsed the grim dogmas of political economy with an alacrity that would only surprise anyone unfamiliar with the long history of our episcopacy’s lamb-like submission to secular liberal orthodoxies. As E.R. Norman pointed out many decades ago, the Church of England’s leaders have, again and again since at least the eighteenth century, “readily adopted the progressive idealism common to liberal opinion within the intelligentsia, of which they were a part”. They have “always managed to reinterpret their sources in ways which have somehow made their version of Christianity correspond to the values of their class and generation”, a process intimately connected to the fact that bishops are nearly always tied (by personal links, economic interests and a desire to conform) to their secular peers who set the broader cultural and political agenda.

Capel Lofft, “The closing of the Episcopal mind”, The Critic, 2022-06-21.

September 27, 2022

QotD: The Poor Law Reform Act of 1834

September 21, 2022

The Medieval Saint Diet

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 20 Sep 2022

(more…)

September 20, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 4 – Justinian, The Hand of God

seangabb

Published 1 Jan 2022Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 19, 2022

City Minutes: Crusader States

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 13 May 2022Crusading is one thing, but holding your new kingdoms is a much trickier business. See how the many Christian states of “Outremer” rolled with the punches to evolve in form and function over multiple centuries.

(more…)

September 16, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 3 – The Age of Justinian – Cashing in the Gains of the Fifth Century

seangabb

Published 7 Dec 2022Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 14, 2022

QotD: The Wars of Religion and the (eventual) Peace of Westphalia

Thomas Hobbes blamed the English Civil War on “ghostly authority”. Where the Bible is unclear, the crowd of simple believers will follow the most charismatic preacher. This means that religious wars are both inevitable, and impossible to end. Hobbes was born in 1588 — right in the middle of the Period of the Wars of Religion — and lived another 30 years after the Peace of Westphalia, so he knew what he was talking about.

There’s simply no possible compromise with an opponent who thinks you’re in league with the Devil, if not the literal Antichrist. Nothing Charles I could have done would’ve satisfied the Puritans sufficient for him to remain their king, because even if he did everything they demanded — divorced his Catholic wife, basically turned the Church of England into the Presbyterian Kirk, gave up all but his personal feudal revenues — the very act of doing these things would’ve made his “kingship” meaningless. No English king can turn over one of the fundamental duties of state to Scottish churchwardens and still remain King of England.

This was the basic problem confronting all the combatants in the various Wars of Religion, from the Peasants’ War to the Thirty Years’ War. No matter what the guy with the crown does, he’s illegitimate. It took an entirely new theory of state power, developed over more than 100 years, to finally end the Wars of Religion. In case your Early Modern history is a little rusty, that was the Peace of Westphalia (1648), and it established the modern(-ish) sovereign nation-state. The king is the king because he’s the king; matters of religious conscience are not a sufficient casus belli between states, or for rebellion within states. Cuius regio, eius religio, as the Peace of Augsburg put it — the prince’s religion is the official state religion — and if you don’t like it, move. But since the Peace of Westphalia also made heads of state responsible for the actions of their nationals abroad, the prince had a vested interest in keeping private consciences private.

I wrote “a new theory of state power”, and it’s true, the philosophy behind the Peace of Westphalia was new, but that’s not what ended the violence. What did, quite simply, was exhaustion. The Thirty Years’ War was as devastating to “Germany” as World War I, and all combatants in all nations took tremendous losses. Sweden’s king died in combat, France got huge swathes of its territory devastated (after entering the war on the Protestant side), Spain’s power was permanently broken, and the Holy Roman Empire all but ceased to exist. In short, it was one of the most devastating conflicts in human history. They didn’t stop fighting because they finally wised up; they stopped fighting because they were physically incapable of continuing.

The problem, though, is that the idea of cuius regio, eius religio was never repudiated. European powers didn’t fight each other over different strands of Christianity anymore, but they replaced it with an even more virulent religion, nationalism.

Severian, <--–>”Arguing with God”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-20.

September 12, 2022

The Lord of the Rings and Ancient Rome (with Bret Devereaux)

toldinstone

Published 10 Sep 2022In this episode, Dr. Bret Devereaux (the blogger behind “A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry”) discusses the relationships between fantasy and ancient history – and why historical accuracy matters, even in fiction.

(more…)

September 9, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 2 – Survival and Growth

seangabb

Published 15 Oct 2021Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

September 3, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 1 – Beginnings

seangabb

Published 1 Oct 2021Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 28, 2022

Church and state, British-style

In The Critic, David Scullion reviews Catherine Pepinster’s book Defenders of the Faith: The British Monarchy, Religion, and the Next Coronation:

The longevity of Elizabeth II has (mostly) allowed us to avert our attention from the question of the relationship between church and state for a very long time. Given that her 70 years on the throne have seen the relentless rise of the forces of philistine secularism and constitutional vandalism, one cannot help but feel grateful for the benign obscurity that her reign has cast over such issues. Alas, this cannot be the case for much longer.

During her coronation in 1953, the Queen made solemn oaths to maintain the “true profession of the Gospel”, “the Protestant Reformed Religion established by law” and the Church of England. She was anointed with holy oil as the chosen ruler of God in a ceremony that owes its ultimate origins to the monarchy of Israel, and which can be traced back in England to at least the coronation of Edgar in 973 AD.

In 1953 this solemn ceremony was received with little in the way of controversy, except in terms of the debate over whether it should be televised. In the end it was, but with the most holy part of the rite — the coming of the Holy Spirit and God’s blessings in the sacred moment of anointing — kept away from the nation’s prying eyes.

If the next coronation is similar, one can only imagine the chorus of outraged, irreverent squawking that will sound from the amassed ranks of secular-liberal opinion-formers. Despite this unappetising prospect, it seems reasonable to discuss what form it should take now, given that 70 years have elapsed since the last one — a task that Catherine Pepinster’s new book purports to undertake.

I say “purports to undertake”, because in fact the vast majority of it is taken up with a rather pedestrian rehearsal of British religious and monarchical history since the Reformation, followed by long and dull accounts of what little we know about the spiritual lives of HM the Queen, Prince Philip and Prince Charles.

These central six chapters of the book are overwhelmingly preoccupied with a topic which clearly concerns the author more than any other: the nature of the relationship between Roman Catholicism and the monarchy, which seems like a rather odd focus given that the British monarchy has not been in communion with the Church of Rome since the 16th century.

She spends a large proportion of the book bewailing the historical inequities perpetrated against Ms Pepinster’s co-religionists by the British establishment, and demonstrating how recent decades have seen a real — albeit cautious — rapprochement between the monarchy and Roman Catholics. She goes on to make a series of commonplace observations about the country’s growing secularism, the rise of religious and cultural diversity, and the decline of Anglican congregations since 1953.

If one wants to know what the equivocating Ms Pepinster thinks the implications of all these trends are for the next coronation and relations between church and state, then one will have to read between the lines. Although her account of the various possibilities is a useful summary, working out what she actually favours is like trying to staple a jellyfish to wet soap.

August 25, 2022

Barbarian Europe: Part 8 – The Franks

seangabb

Published 1 Sep 2021In 400 AD, the Roman Empire covered roughly the same area as it had in 100 AD. By 500 AD, all the Western provinces of the Empire had been overrun by barbarians. Between April and July 2021, Sean Gabb explored this transformation with his students. Here is one of his lectures. All student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

August 20, 2022

QotD: The improbable survival of the Byzantine empire

The [Eastern Roman] Empire was faced by a triple threat to its existence. There were the northern barbarians. There was militant Islam in the south. There was an internal collapse of population. Each of these had been brought on by changes in the climate that no one at the time could have understood had they been noticed. It would not be until after 800 that the climate would turn benign again. In the meantime, any state to which even a shadow of Lecky’s dismissal applied would have crumpled in six months. Only the most courageous and determined action, only the most radical changes of its structure, could save the Empire. And saved the Empire most definitely was.

The reason for this is that the Mediaeval Roman State was directed by creative pragmatists. Look for one moment beneath its glittering surface, and the Ancient Roman Empire was a ghastly place for most of the people who lived in it. The Emperors at the top were often vicious incompetents. They ruled through an immense and parasitic bureaucracy. They were supreme governors of an army too large to be controlled. They protected a landed aristocracy that was a repository of culture, but that was ruthless in its exaction of rent. Most ordinary people were disarmed tax-slaves, where not chattel slaves or serfs.

The contemporary historians themselves are disappointingly vague about the seventh and eighth centuries. Our only evidence for what happened comes from the description of established facts in the tenth century. As early as the seventh century, though, the Mediaeval Roman State pulled off the miracle of reforming itself internally while fighting a war of survival on every frontier. Much of the bureaucracy was shut down. Taxes were cut. The silver coinage was stabilised. Above all, the senatorial estates were broken up and given to those who worked on them, in return for service in local militias. Though never abolished, chattel slavery became far less pervasive. The civil law was simplified, and the criminal law humanised – after the seventh century, as said, the death penalty was rarely used.

The Mediaeval Roman Empire survived because of a revolutionary transformation in which ordinary people became armed stakeholders. The inhabitants of Roman Gaul and Italy and Spain barely looked up from their ploughs as the Barbarians swirled round them. The citizens of Mediaeval Rome fought like tigers in defence of their country and their Orthodox faith. Time and again, the armies of the Caliph smashed against a wall of armed freeholders. This was a transformation pushed through in a century and a half of recurrent crises during which Constantinople itself was repeatedly under siege. Alone among the ancient empires in its path, Mediaeval Rome faced down the Arabs, and kept Islam at bay for nearly five centuries. Would it be superfluous to say that no one does this by accident?

Sean Gabb, “The Mediaeval Roman Empire: An Unlikely Emergence and Survival”, SeanGabb.co.uk, 2018-09-14.

August 19, 2022

Why Quebec rejected the American Revolution

Conrad Black outlines the journey of the French colony of New France through the British conquest to the (amazing to the Americans) decision to stay under British control rather than join the breakaway American colonies in 1776:

Civil rights were not a burning issue when Canada was primarily the French colony of New France. The purpose of New France was entirely commercial and essentially based upon the fur trade until Jean Talon created industries that made New France self-sufficient. And to raise the population he imported 1,000 nubile young French women, and today approximately seven million French Canadians and Franco-Americans are descended from them. Only at this point, about 75 years after it was founded, did New France develop a rudimentary legal and judicial framework.

Eighty years later, when the British captured Québec City and Montréal in the Seven Years’ War, a gentle form of British military rule ensued. A small English-speaking population arose, chiefly composed of commercial sharpers from the American colonies claiming to be performing a useful service but, in fact, exploiting the French Canadians. Colonel James Murray became the first English civil governor of Québec in 1764. A Royal proclamation had foreseen an assembly to govern Québec, but this was complicated by the fact that at the time British law excluded any Roman Catholic from voting for or being a member of any such assembly, and accordingly the approximately 500 English-speaking merchants in Québec demanded an assembly since they would be the sole members of it. Murray liked the French Canadians and despised the American interlopers as scoundrels. He wrote: “In general they are the most immoral collection of men I ever knew.” He described the French of Québec as: “a frugal, industrious, moral race of men who (greatly appreciate) the mild treatment they have received from the King’s officers”. Instead of facilitating creation of an assembly that would just be a group of émigré New England hustlers and plunderers, Murray created a governor’s council which functioned as a sort of legislature and packed it with his supporters, and sympathizers of the French Canadians.

The greedy American merchants of Montréal and Québec had enough influence with the board of trade in London, a cabinet office, to have Murray recalled in 1766 for his pro-French attitudes. He was a victim of his support for the civil rights of his subjects, but was replaced by a like-minded governor, the very talented Sir Guy Carleton, [later he became] Lord Dorchester. Murray and Carleton had both been close comrades of General Wolfe. […]

The British had doubled their national debt in the Seven Years’ War and the largest expenses were incurred in expelling the French from Canada at the urgent request of the principal American agent in London, Benjamin Franklin. As the Americans were the most prosperous of all British citizens, the British naturally thought it appropriate that the Americans should pay the Stamp Tax that their British cousins were already paying. The French Canadians had no objection to the Stamp Tax, even though it paid for the expulsion of France from Canada.

As Murray and Carleton foresaw, the British were not able to collect that tax from the Americans; British soldiers would be little motivated to fight their American kinfolk, and now that the Americans didn’t have a neighboring French presence to worry them, they could certainly be tempted to revolt and would be very hard to suppress. As Murray and Carleton also foresaw, the only chance the British would have of retaining Canada and preventing the French Canadians from rallying to the Americans would be if the British crown became symbolic in the mind of French Canada with the survival of the French language and culture and religion. Carleton concluded that to retain Québec’s loyalty, Britain would have to make itself the protector of the culture, the religion, and also the civil law of the French Canadians. From what little they had seen of it, the French Canadians much preferred the British to the French criminal law. In pre-revolutionary France there was no doctrine of habeas corpus and the authorities routinely tortured suspects.

In a historically very significant act, Carleton effectively wrote up the assurances that he thought would be necessary to retain the loyalty of the colony. He wanted to recruit French-speaking officials from among the colonists to give them as much self-government as possible while judiciously feeding the population a worrisome specter of assimilation at the hands of a tidal wave of American officials and commercial hustlers in the event of an American takeover of Canada.

After four years of lobbying non-stop in London, Carleton gained adoption of the Québec Act, which contained the guaranties he thought necessary to satisfy French Canada. He returned to a grateful Québec in 1774. The knotty issue of an assembly, which Québec had never had and was not clamoring for, was ducked, and authority was vested in a governor with an executive and legislative Council of 17 to 23 members chosen by the governor.

Conveniently, the liberality accorded the Roman Catholic Church was furiously attacked by the Americans who in their revolutionary Continental Congress reviled it as “a bloodthirsty, idolatrous, and hypocritical creed … a religion which flooded England with blood, and spread hypocrisy, murder, persecution, and revolt into all parts of the world”. The American revolutionaries produced a bombastic summary of what the French-Canadians ought to do and told them that Americans were grievously moved by their degradation, but warned them that if they did not rally to the American colours they would be henceforth regarded as “inveterate enemies”. This incendiary polemic was translated, printed, and posted throughout the former New France, by the Catholic Church and the British government, acting together. The clergy of the province almost unanimously condemned the American agitation as xenophobic and sectarian incitements to hate and needless bloodshed.

Carleton astounded the French-Canadians, who were accustomed to the graft and embezzlement of French governors, by not taking any payment for his service as governor. It was entirely because of the enlightened policy of Murray and Carleton and Carleton’s skill and persistence as a lobbyist in the corridors of Westminster, that the civil and cultural rights of the great majority of Canadians 250 years ago were conserved. The Americans when they did proclaim the revolution in 1775 and officially in the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, made the British position in Canada somewhat easier by their virulent hostility to Catholicism, and to the French generally.

August 12, 2022

Testing the old saying about those who believe in nothing will believe anything

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander considers the old saying — often mis-attributed to G.K. Chesterton or C.S. Lewis:

There’s a popular saying among religious apologists:

Once people stop believing in God, the problem is not that they will believe in nothing; rather, the problem is that they will believe anything.

Big talk, although I notice that this is practically always attributed to one of GK Chesterton or CS Lewis, neither of whom actually said it. If you’re making strong claims about how everybody except you is gullible, you should at least bother to double-check the source of your quote.

Still, it’s worth examining as a hypothesis. Are the irreligious really more likely to fall prey to woo and conspiracy theories?

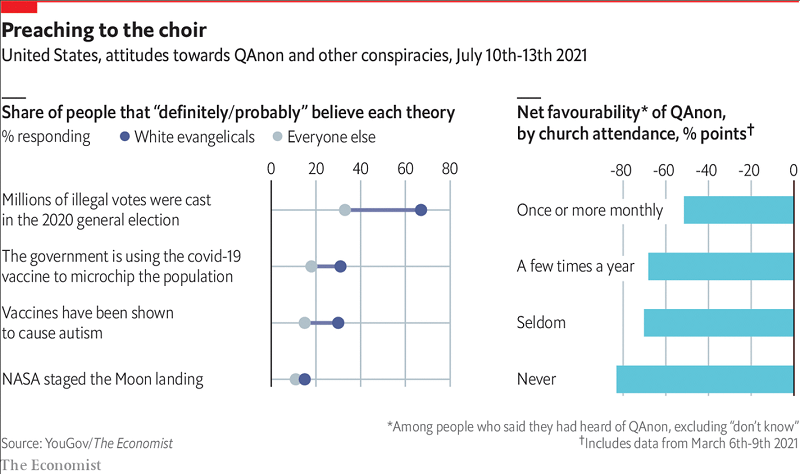

This Economist article examined the question and concluded the opposite. See especially this graph:

“White evangelicals” are more likely to believe most measured conspiracy theories, and churchgoers were more likely to believe in QAnon in particular.

There’s an obvious confounder here: the authors are doing the usual trick where they cherry-pick right-wing examples of something bad, show that more right-wingers are in favor of them, then conclude that Science Has Proven Right-Wingers Are Bad. QAnon, illegal votes, and COVID microchips are inherently right wing conspiracy theories; vaccines/autism has probably become right-coded post-COVID. Only the moon landing seems politically neutral, and it’s hard to tell if there’s a real difference on that one. So this just tells us that white evangelical church-goers are further right than other people, which we already know.

These data still deflate some more extreme claims about religion being absolutely protective against conspiracy theories. But I was interested in seeing how people of different faiths related to politically neutral conspiracies.

QotD: Diplomatic adventures in the British Foreign Office

Lord Chalfont tells a story about his days as a Junior Minister in the Foreign Office. He attended a very grand dinner party, and spotted a lady standing alone in a long red dress. The besotted Chalfont staggered across to ask if she would waltz with him … The lady drew herself up: “I will not waltz with you for three reasons. First this is not a waltz it is the Czech national anthem. Second, you are drunk. My third and greatest objection is that I am the Cardinal Archbishop of Prague”.

Auberon Waugh, Diary, 1976-05-02 (Posted by @AuberonWaugh_PE, 2022-05-02).