Spencer Fernando, writing for the National Citizens Coalition:

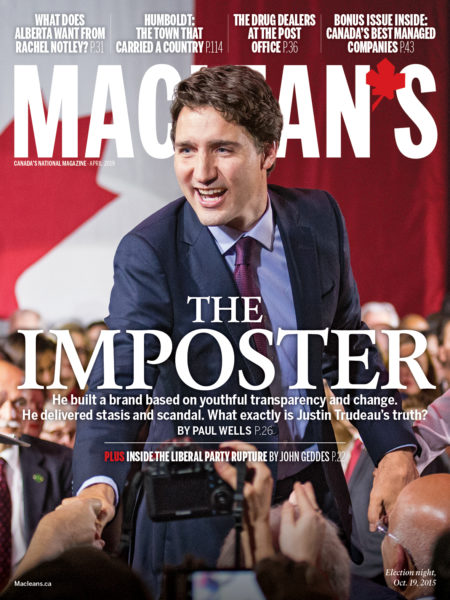

When trying to ascertain where the Trudeau Liberals are trying to take the country, it’s important to look at the foundations of Justin Trudeau’s worldview.

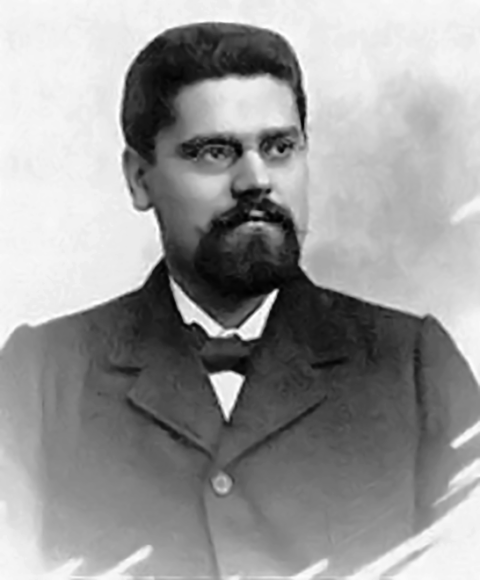

Clearly, he was heavily influenced by his father, someone who continuously expanded the power of the state.

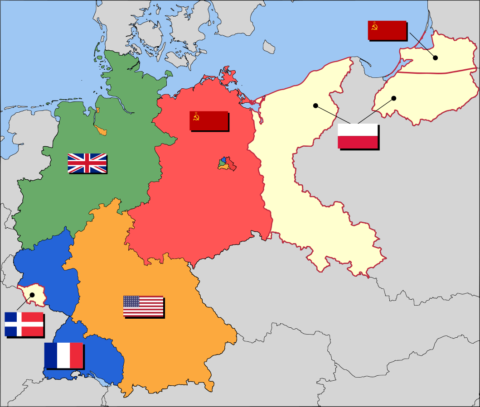

Justin Trudeau’s father was well known as a Communist-sympathizer, being a big fan of both Fidel Castro and Communist China.

Note, the version of the CCP that existed in Pierre Trudeau’s era was even more brutal than the CCP as it exists today. At the time, it was not far removed from the time of Mao’s Great Leap Forward, a government-imposed “reshaping of society” that led to roughly 45 million deaths.

To look at that, and still be a fan of the Chinese Communist Party, is to show a deep ideological commitment to authoritarian socialism and a deep aversion to human freedom.

The apple clearly didn’t fall far from the tree, as Justin Trudeau praised China’s “basic dictatorship” (AKA the centralized power structure that enables horrific crimes).

Trudeau also sought to move Canada closer to China’s orbit, only giving up on that when public opinion – and a subtle revolt among some backbench Liberals – rendered it politically unfeasible.

We can see how the authoritarian socialism that Trudeau praised in China (and let’s not forget his fawning eulogy for Fidel Castro), lines up with the fear and contempt he and the Liberals have for many Canadians.

Now, let’s also note this essential point:

The Liberals continuously target the same individuals that authoritarian socialists and communists have targeted:

Rural Conservatives.

Private Enterprise.

Religious Groups.

Freethinkers.

Individualists.

Private Farmers.

Rural Gun Owners.

Independent Press Outlets.

Historically, those are all groups that the far-left has targeted when given the opportunity.

We only need to look at how the Liberal approach to Covid was modelled after the approach taken by Communist China, and how both the Liberals and the CCP have been largely unwilling to move on.

While the Liberals are more constrained than the CCP by the fact that Canada maintains some freedoms, do we have any doubt that they would be far more severe if they could get away with it?

Remember, the moment he feared losing the 2021 election, Justin Trudeau used very divisive and disturbing rhetoric (especially disturbing when seen in a historical context), and purposely sought to direct hatred and blame towards those who resisted draconian state orders.

Since then, the Trudeau Liberals – even in the face of criticism by a few courageous Liberal MPs who were quickly “put back in their place” – have almost gleefully abused their power, purposely creating an “Us vs Them” narrative designed to pit Canadians against each other.

At the same time, they’ve continued their efforts to gain control over social media, silence dissenting views, and turn the establishment media into an extension of the state propaganda apparatus.

This is all being done because they fear those who have the intelligence and strength of character to see through their agenda.

They fear you, and have contempt for you.