… before we get into the design of point defenses, we should talk about what these are for. Generally, fixed point defenses of this sort in the pre-modern world are meant to control the countryside around them (which is where most of the production is). This is typically done through two mechanisms (and most of point defenses will perform both): first by housing the administrative center which organizes production in the surrounding agricultural hinterland (and thus can extract revenue from it) and second by creating a base for a raiding force which can at least effectively prohibit anyone else from efficiently extracting revenue or supplies from the countryside. Consequently if we imagine the extractive apparatus of power as a sort of canvas stretched over the countryside, these fortified administrative centers are the nails that hold that canvas in place; to take and hold the land, you must take and hold the forts.

In the former case, the fortified center contains three interlinked things: the local market (where the sale of agricultural goods and the purchase by farmers of non-agricultural goods can be taxed and controlled), a seat of government that wields some customary power to tax the countryside through either political or religious authority and finally the residences of the large landholders who own that land and thus collect rents on it (and all of these things might also come with significant amounts of moveable wealth and an interest in protecting that too). For a raiding force, the concentration of moveable property (money, valuables, stored agricultural goods) this creates a tempting target, while for a power attempting to conquer the region the settlement conveniently already contains all of the administrative apparatus they need to extract revenue out of the area; if they destroyed such a center, they’d end up having to recreate it just to administer the place effectively.

In the latter case, the presence of a fortified center with even a modest military force makes effective exploitation of the countryside for supplies or revenue by an opposing force almost impossible; it can thus deny the territory to an enemy since pre-industrial agrarian armies have to gather their food locally. We have actually already discussed this function of point defenses before: the presence of a potent raiding force (typically cavalry) within allows the defender to strike at either enemy supply lines (should the fortress be bypassed) or foraging operations (should the army stay in the area without laying siege) functionally forcing the attacker to lay siege and take the fortress in order to exploit the area or move past it.

In both cases, the great advantage of the point defense is that while it can, through its administration and raiding threat, “command” the surrounding hinterland, the defender only needs to defend the core settlement to do that. Of course an attacker unable or unwilling to besiege the core settlement could content themselves with raiding the villages and farms outside of the walls, but such actions don’t accomplish the normal goal of offensive warfare (gaining control of and extracting revenue from the countryside) and peasants are, as we’ve noted, often canny survivors; brief raids tend to have ephemeral effects such that actually achieving lasting damage often requires sustained and substantial effort.

All of which is to say that even from abstract strategic reasoning, focusing considerable resources on such fortifications is a wise response to the threat of raids or invasion, even before we consider the interests of the people actually living in the fortified point (or close enough to flee to it) who might well place a higher premium on their own safety (and their own stuff!) than an abstract strategic planner would. The only real exception to this were situations when a polity was so powerful that it could be confident in its ability to nearly always win pitched battles and so prohibit any potential enemy from getting to the point of laying siege in the first place. Such periods of dominance are themselves remarkably rare. The Romans might be said to have maintained that level of dominance for a while, but as we’ve seen they didn’t abandon fortifications either.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part III: Castling”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-10.

March 19, 2025

QotD: The purpose of fortification

March 18, 2025

“[T]he Liberals have no principles because it works“

The first act of our unelected prime minister was to performatively sign a piece of paper that supposedly eliminated the hated carbon tax. Well, part of the carbon tax. And not really eliminated eliminated, it just set the rate to zero percent. The carbon tax that the Liberals had proclaimed was essential to saving the entire planet from global warming. If this seems odd, buckle up, because this is just how the Liberal Party operates:

Obviously, I don’t believe Mark Carney nor the Liberal Party of Canada want to destroy the world.

Nor do I believe they could destroy the world, even if a supervillain gave them an unlimited budget in which to do so. After ten years when the supervillain checked up on the Liberals to see how the world-destruction plan was coming along, he’d find out that the world destruction equity subcommittee was waiting for a report from a sub-subcommittee responsible for convening a task force to authorize a panel to determine how to destroy the world in way which minimally impacted disadvantaged communities, but they’re having trouble finding francophone Saskatchewanians for the breakout sessions.

But I am somewhat startled to see how quickly Carney’s Liberal Party abandoned a signature policy it assured us was necessary to fight the existential threat posed by climate change:

This is like the National Socialist German Workers Party tweeting a meme cheering on Adolf Hitler for killing Hitler. (Given the state of Twitter these days, I wouldn’t be surprised if there actually is an official NSDAP account, but never mind.)

We’re left with two possibilities regarding the carbon tax policy promoted by the last Liberal Prime Minister and now abolished (or is it?!?) by the new Liberal Prime Minister:

- it never would have made much difference in the fight against climate change anyway, in which case it was always a waste of time and effort; or,

- it would have made a big difference in the fight against climate change, in which case Carney has decided it’s more important to win the impending federal election and take away his opponents’ talking points than to actually do something about a potential ecological crisis.

I’m not naive about politicians, even those I support, being hypocrites and flip-floppers. There may be some truly principled, ideologically consistent political parties out there, but they can hold their annual conventions in a Ford Club Wagon.

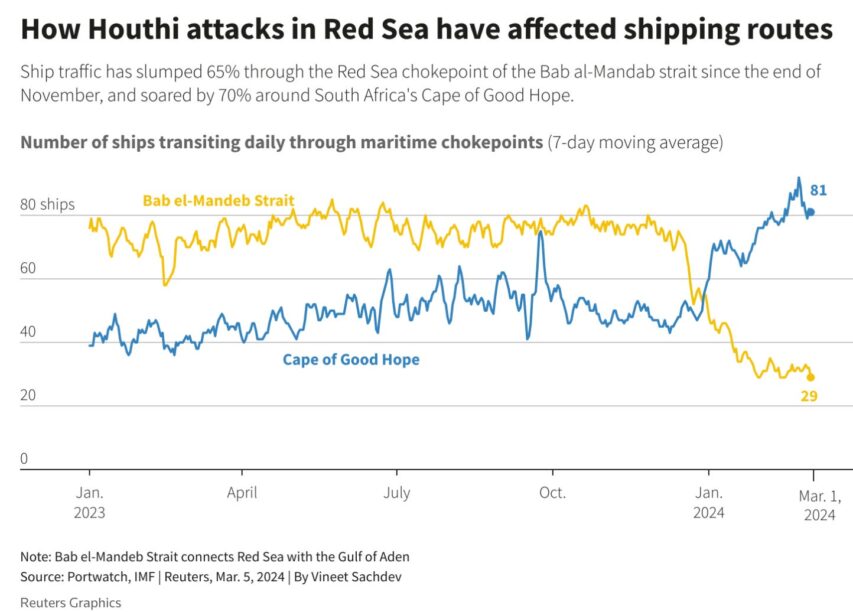

Getting rid of Houthi and the Blowfish

It has been alarming just how long the west — and especially the United States — have been willing to put up with Houthi attacks on shipping going through the Red Sea. President Trump has indicated that American patience has run out, as CDR Salamander discusses:

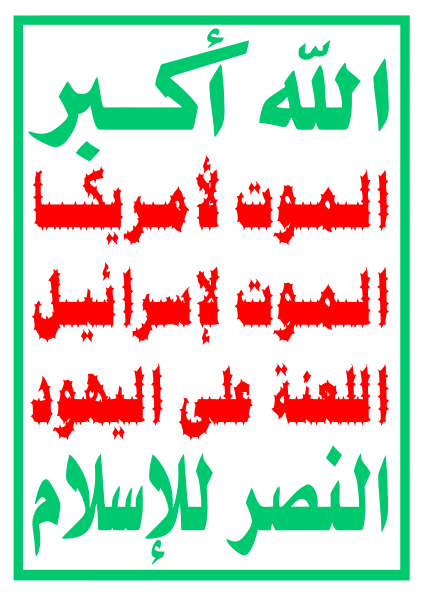

The Houthi Ansarullah “Al-Sarkha” banner. Arabic text:

الله أكبر (Allah is the greatest)

الموت لأمريكا (death to America)

الموت لإسرائيل (death to Israel)

اللعنة على اليهود (a curse upon the Jews)

النصر للإسلام (victory to Islam)

Image and explanatory text from Wikimedia Commons.

… in the almost 18 months since the Houthi rebels have been attacking Western shipping in the Red Sea, we have mostly been playing defense.

Why have we been playing defense? The Biden Administration, like the Obama Administration, was worm-ridden with Iranian accommodationalists. The Houthi, like Hamas and Hezbollah, are Iranian proxies.

After the murder, rape, slaughter, and kidnapping from Gaza into Israel on October 7th, 2023 by Iranian proxies, the Houthi started their campaign of support — as directed by Iran — by attacking shipping in the Red Sea.

It could not be ignored, but we never took the needed action. We did not even do half-measures. At best we did quarter-measures.

The attacks continued and our credibility on the world stage degraded in proportion to that.

As we have discussed often here, we have a few thousand years of dealing with piracy and bad-faith actors on the high seas. It has direct costs in commerce, treasure, and lives.

This cannot be allowed to continue.

Over the weekend, the new Trump Administration put down a marker. We seem to have ratcheted things up a bit. Not much available on open source, but over the weekend, CENTCOM put out a few things;

CENTCOM Forces Launch Large Scale Operation Against Iran-Backed Houthis in Yemen On March 15, U.S. Central Command initiated a series of operations consisting of precision strikes against Iran-backed Houthi targets across Yemen to defend American interests, deter enemies, and restore freedom of navigation.

[…]

Where is all this going? Well, let’s establish a few things first.

- Clearly what we were doing was not working.

- The Houthi are a 4th rate non-naval power. We like to tell everyone that, though we are the world’s second largest navy, we are the most capable. If we can’t keep the Houthi away from shipping through a major Sea Line of Communication, then why should anyone expect we could do more.

- Europe won’t/can’t help. They not only lack the capability to project power ashore against the Houthi to any reasonable measure, they lack the will.

- China does not care. It does not impact them. They benefit from this chaos against the West.

- Russia thinks this is wonderful.

- Iran can’t believe we are letting this go on. The Houthi are the last significant proxy, so they will do all they can to keep them going.

The lines are fairly clear right now. Not much room to maneuver. Looks like we will be at this for awhile. More extended range time.

Ancient Roman Cheesecake – Savillum

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 5 Nov 2024Ancient Roman cheesecake drizzled with honey and sprinkled with poppy seeds

City/Region: Rome

Time Period: 2nd Century BCAncient Romans took their feasting very seriously. If you had the money, a feast could be made up of several courses, starting with hors d’oeuvres and aperitifs and ending with sweet dishes. These dessert-type foods were sweetened with fruit or honey, like this cheesecake.

This savillum is very dense, and also quite flavorful and tasty. With the amount of honey I used, it’s not as sweet as a modern cheesecake, but you can see how it has evolved over the last two thousand years. What type of cheese you use will make a big difference in the flavor of your cheesecake. I used ricotta, and my cheesecake was smooth and mild with a prominent honey flavor, but if you choose a stronger flavored cheese, I think it’ll be the main note coming through.

Make the savillum this way. Take half a pound of flour and two and a half pounds of cheese, and mix together as for the libum. Add 1/4 pound of honey and 1 egg. Grease an earthenware dish with oil. When you have mixed the ingredients well, pour into the dish and cover it with an earthenware lid. See that you cook it well in the middle, where it is thickest. When it is cooked, remove the dish, coat with honey, sprinkle with poppy seeds, and put it back beneath the lid for a short while, then remove from the fire. Serve it in the dish with a spoon.

— De Agri Cultura by Marcus Porcius Cato, 2nd Century BC

QotD: Lester Thurow and the other cheerleaders for “Industrial Policy” in the 1980s

The late Lester Thurow was quite popular in the 1980s and 1990s for his incessant warnings that America was losing at the game of trade with other countries. Most ominous, Thurow (and others) warned, was our failure to compete effectively against the clever Japanese who, unlike us naive and complacent Americans, had the foresight to practice industrial policy, including the use of tariffs targeted skillfully and with precision. Trade, you see, said Thurow (and others) is indeed a contest in which the gains of the “winners” are the losses of the “losers”. Denials of this alleged reality come only from those who are bewitched by free-market ideology or blinded by economic orthodoxy.

And so – advised Thurow (and others) – we Americans really should step up our game by taking many production and consumption decisions out of the hands of short-sighted and selfish entrepreneurs, businesses, investors, and consumers and putting these decisions into the hands of the Potomac-residing wise and genius-filled faithful stewards of Americans’ interest.

Sound familiar? It should. While some of the details from decades ago of the news-making proponents of protectionism and industrial policy differ from the details harped on by today’s proponents of protectionism and industrial policy, the essence of the hostility to free trade and free markets of decades ago is, in most – maybe all – essential respects identical to the hostility that reigns today.

Markets in which prices, profits, and losses guide the decisions of producers and consumers were then – as they are today – asserted to be stupid, akin to a drunk donkey, while government officials (from the correct party, of course) alone have the knowledge, capacity, willpower, and power to allocate resources efficiently and in the national interest.

Nothing much changes but the names. Three or four decades ago protectionism and industrial policy in the name of the national interest was peddled by people with names such as Lester Thurow, Barry Bluestone, and Felix Rohatyn. Today protectionism and industrial policy in the name of the national interest is peddled by people with different names.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2020-03-12.

March 17, 2025

America’s modern Triumvirate

Last month, I posted John Carter’s amusing riff on Trump, Musk, and Vance as the American Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar, the original Triumvirate. Apparently John isn’t the only one struck by the similarities, as David Friedman also considers the three as America’s modern Triumvirate:

Trump is the most important at present, since both Vance and Musk have political power only to the extent he gives it to them. He is a very competent demagogue, as demonstrated by his winning a series of political conflicts that almost everyone expected him to lose. So far as I can tell from his history he has no political views of his own, uses ideology as a tool to get power, attention, status. Conservatives were a substantial faction unhappy with the state of the nation, with what they viewed as the political and cultural domination of the country by their opponents, hence a potential power base for him. Progressives had overplayed their hand, pushed woke ideology too far, due to face a backlash, useful as enemies. He adopted the role of conservative champion, destroyer of wokeism, borrowing details of his program most recently from Project 2025, a detailed conservative plan for how a conservative administration could restructure the federal government.

Trump’s Ukraine policy is to produce a peace for which he could claim credit, a deal that holds until at least 2028. To force Zelensky to accept he had to make it believable that he was willing to drop US support for Ukraine if Ukraine refuses to go along, and he did. To force Putin to accept he will have to make it believable that the US is willing to continue, even expand, support for Ukraine if Russia refuses to accept a peace plan.

[…]

Assuming no rupture with Trump and no failure of their administration extreme enough to break Trump’s control over his party, Vance will be the Republican nominee in 2028. He is young, handsome and smart with a beautiful and intelligent wife, is playing a minor role now but could be a major political figure in the post-Trump world. Unlike Trump he has political views of his own, not merely the desire for power. What are they?

I devoted two of my earlier posts to trying to answer that question, Vance and Revising the Republican Party. My conclusion:

The conservative movement of Bill Buckley rejected the New Deal. Vance does not. The past he wants to return to is an idealized version of America in the fifties, perhaps the sixties. The movement he wants to build rejects both the pro-market economics of the pre-Trump conservative movement and the cultural program of current progressives. He wants an America of stable marriages, views parents as more reliably committed to the future than the childless — hence the much-quoted line about childless cat ladies. One of his more intriguing proposals is that children should get votes, cast by their parents, giving a family with three children five votes.

…

The Republican party Vance wants to build looks, economically, like the Democratic party of the fifties and sixties, culturally like the inverse of the progressive, aka woke, movement.

[…]

The project the three of them are attempting is a full scale revision of the federal government. Of the three, Musk is the one who might be competent to do it. Trump’s skill is charisma, the ability to get people to pay attention to him, admire him, want to please him. That is how he got to a position from which to revise the government but it is not the skill needed to do it. Vance has demonstrated even less of the relevant abilities; his accomplishments so far are writing a very interesting book and winning a senate election

Musk, in contrast, has created two very successful firms, taken over and revised a third. None were projects on the scale of what he is now attempting but they are smaller projects of the same sort. Hence it is at least possible that, with the authority Trump has so far been willing to delegate to him, he can convert the federal government into something smaller, less expensive, better functioning, judged at least by the standards of Trump and his supporters.

My Big Fat Greek Civil War – W2W 12 – 1947 Q2

TimeGhost History

Published 16 Mar 2025As Europe emerges from WWII, Greece plunges into chaos. Political polarization, revenge killings, and failed diplomacy ignite a bitter civil war, turning former allies into deadly foes. From communist partisans regrouping in the mountains, to royalists asserting brutal dominance, the battle lines are drawn. Could Greece become the first major flashpoint in the Cold War, threatening peace across the Balkans and beyond?

(more…)

German politicians are willing to literally bankrupt the country to keep the AfD out of power

eugyppius is clearly no fan of Friedrich Merz, the CDU leader and presumptive next Chancellor of Germany, but even he seems boggled at how much Merz is willing to concede to his ideological enemies to get himself into that position:

Let us summarise, briefly, what has happened so far:

- The CDU are the party of fiscal responsibility. His Triviality the Pigeon Chancellor Friedrich Merz presented himself throughout the campaign as an unusual fan of Germany’s constitutionally-anchored debt brake. He told everybody that he could not imagine ever borrowing in excess of 0.35% of annual GDP, so interested was he in limiting the tax burden of future generations.

- All of the while, Merz and his advisers were scheming in secret about how they might overhaul the debt brake, firstly because they could not give the slightest shit about the tax burdens of future generations, and secondly because they spent the months since November 2023 observing what happens when a government that has no ideas is also deprived of money. “I have no ideas,” Merz said to himself during this time. “What happens if like Olaf Scholz I also end up with no money?”

- Exactly two weeks ago, U.S. President Donald J. Trump and Ukrainian President Vladimir Zelensky had a verbal spat in the Oval Office. This spat put the fear of God into the Eurocrat establishment, for whom the Ukraine war has become a sacred and essentially religious cause. Merz capitalised on the panic to unveil his massive debt spending plan. He and his would-be coalition partners, the Social Democrats, announced that they wished to spend 500 billion Euros of debt on “infrastructure” and untold hundreds of billions of debt on defence. This would entail adjustments to the debt brake, in the same way setting your house on fire would entail adjustments to your living arrangements.

- This massive spending package will require a constitutional amendment, which can only be achieved with a two-thirds vote of the Bundestag. In the newly elected Bundestag, Die Linke and AfD will be in a position to block this amendment and Merz will be stuck with the debt brake. Thus Merz wants to break the debt brake in the final days of the old Bundestag – a strategy that has put him in the amazing position of groveling before the election’s biggest losers. Specifically, Merz has spent the past few days feverishly negotiating with the Green Party, who will not even have any role in his government, just to get them to sign off on his insane spending plans.

I wrote a lot here and on Twitter about the election nightmare scenario I called the “Kenyapocalypse” – a hypothetical in which the Greens and the Social Democrats would each be too weak to give the Union parties a majority on their own, such that Friedrich Merz would be forced to negotiate a coalition deal with both of them at once. In the end, Kenyapocalypse did not happen; the CDU avoided it by a razor’s breadth. Merz, however, turns out to be such a monumental retard that he has managed to recreate a simulacrum of Kenyapocalypse for himself. The man has been on his knees kissing not only Social Democrat but also Green ass for days. He has been begging the Greens to sign onto his debt plan, and the Greens have finally agreed, in return for the following concessions:

- The “defence” funding that will be exempt from the debt brake is to be defined as widely as possible. All kinds of things will count as debt brake-exempt “defence” spending now, probably including various climate nonsense.

- The 500 billion-Euro “infrastructure” debt is to include 100 billion Euros specifically earmarked for the “Climate and Transformation Fund” – the central financial instrument of the energy transition. This is basically infinity windmill money, you might as well set it on fire. Beyond this specific allocation, any projects that contribute to making Germany “climate neutral by 2045” will also be eligible for the 500 billion-Euro exception. This whole thing will be a massive wad of debt for Green nonsense and I would like to take this moment to laugh at everyone who told me how happy I should be that Merz was trying to fix Germany’s bridges with this debt bullshit. Nothing of the sort is going to happen.

- You will note that the explicit goal of achieving “climate neutrality” by 2045 is slated to be among the very few positive political points anchored in the German constitution. “Climate neutrality” is a more expansive concept than mere “carbon neutrality”, or net zero. It describes a utopian state of affairs in which human actions have no influence on the climate whatsoever.

These are prizes the Greens could not achieve even at the height of their influence, in the 2021 elections. Strictly speaking, the entire traffic light coalition fell apart over a matter of 3 billion Euros. Now the Greens are getting 100 billion Euros for free, all because Merz is determined to become Chancellor whatever the cost.

How to Make Irish Shepherd’s Pie | Food Wishes

Food Wishes

Published 5 Mar 2012Learn how to make an Irish Shepherd’s Pie! This recipe is a lovely alternative to the much more common corned beef and cabbage recipe that you may have been planning for dinner. Take things to the next level with some nice Irish cheddar.

St. Patrick’s Day Special: Irish Shepherd’s Pie (the real one, not the stuff they eat in cottages)

I know I may have used a few atypical ingredients in this, but as far as I’m concerned, the only two things that are mandatory to make a “real” Shepherd’s Pie are potatoes and lamb. While the ground beef version is also very delicious, it’s not considered a “Shepherd’s Pie”, since shepherds raise sheep, not cows.

The real mystery is why the beef version is called “Cottage Pie”, and not “Cowboy Pie”, or “Rancher’s Pie”. When I think about cattle, many things come to mind, but cottages aren’t one of them. Okay, now that we have all those search keywords inserted, we can moooo’ve on.

By the way, I know it’s something of a Food Wishes tradition that I do a cheap, culturally insensitive joke about Irish-Americans drinking too much in our St. Patrick’s Day video, but this year I decided not to do any. In fairness, I know hundreds of Irish people, and several of them have no drinking problem whatsoever, so it just didn’t seem inappropriate.

Anyway, as I say in the video, this would make a lovely alternative to the much more common corned beef and cabbage that you may have been planning for dinner. Also, I really hope you find some nice Irish cheddar. I used one called “Dubliner” by Kerrygold, which can be found in most large grocery stores.

If you’re curious about beverage pairings, may I go out on a limb and suggest a nice Guinness, or other Irish beer … just hold the green food coloring, please. Erin go bragh, and as always, enjoy!

(more…)

QotD: Myths from Norman Rockwell’s America

I’ve seen complaints on X that a factory worker’s single income used to be enough to raise a family on but isn’t anymore. It’s true; I grew up in those days.

The complaint generally continues that we were robbed of this by bad policy choices. But that is at best only half true.

World War II smashed almost the entire industrial capacity of the world outside the U.S., which exited with its manufacturing plant not only intact, but greatly improved by wartime capitalization. The result was that for about 30 years, the US was a price-taker in international markets. Nobody could effectively compete with us at heavy or even light manufacturing.

The profits from that advantage built Norman Rockwell’s America — lots of prosperous small towns built around factories and mills. Labor unions could bid up salaries for semi-skilled workers to historically ridiculous levels on that tide.

But it couldn’t last. Germany and Japan and England recapitalized and rebuilt themselves. The Asian tigers began to be a thing. U.S. producers facing increasing competitive pressure discovered that they had become bloated and inefficient in the years when the penalty for that mistake was minimal.

Were there bad policy choices? Absolutely. Taxes and entitlement spending exploded because all that surplus was sloshing around ready to be captured; the latter has proven politically almost impossible to undo.

When our windfall finally ended in the early 1970s, Americans were left with habits and expectations formed by the long boom. We’ve since spent 50 years trying, with occasional but only transient successes, to recreate those conditions. The technology boom of 1980 to 2001 came closest.

But the harsh reality is that we are never likely to have that kind of advantage again. Technology and capital are now too mobile for that.

Political choices have to be made within this reality. It’s one that neither popular nor elite perception has really caught up with.

Eric S. Raymond, X (the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, 2024-07-08.

March 16, 2025

Female sexual predators

Every civilized person rejects the notion that male sexual predators should be tolerated, yet few are willing to accept the notion that female sexual predators might even exist. They absolutely do exist and they do commit terrible crimes against their — often very young — victims, as Janice Fiamengo shows:

Even when we are aware that women prey on children, many of us can’t really believe it. When Florida Congresswoman Anna Luna, a Republican elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, proposed three new bills last year that would impose harsh penalties, “including the death penalty”, for various forms of sexual abuse, child pornography, and child sexual exploitation, it is impossible to believe that Luna thought any number of women would be executed for child rape, and nor will they be given the leniency that is shown to women in the criminal justice system (see Sonja Starr’s research).

Yet similar crimes to Ma’s are easily discovered. In the same month that Ma pled guilty, a Martinsville, Indiana teacher was charged with three counts of sexual misconduct against a minor, a 15-year-old boy who has alleged that as many as ten other students were raped by the same woman. The month before that, a New Jersey primary school teacher was charged with aggravated sexual assault against a boy who was 13 years old when she bore his child; it is alleged that she began raping the boy when he was 11. The month before that, a Tipton County, Tennessee teacher [pictured below] pled guilty to a dozen sex crimes against children ranging in age from 12-17 years old. It is thought that she victimized a total of 21 children.

In the same month, a Montgomery, New York teacher pled guilty to criminal sexual assault of a 13 year old boy in her class, whom she assaulted over a period of months. In the previous month, a San Fernando Valley teacher was charged with sexual assault of a 13 year old male student; police believe she victimized others also. Earlier in the year, a substitute teacher in Decatur, Illinois was charged with raping an 11 year old boy. These are just a few recent cases, and only those involving female schoolteachers. Female predators are also to be found amongst social workers, juvenile detention officers, and sports coaches.

The feminist position on male sexual abuse of women and girls has for a long time been that it is about power. Men rape and abuse, according to Susan Brownmiller [quoted above] and others, because they believe it their right as men to keep women subordinate. Rape compensates for male inadequacy and allows for the expression of men’s hostility toward women: it is not about lust but about men’s need to humiliate and degrade. As Paul Elam once noted in a Regarding Men episode, the theory is fatally weakened if even a single woman does the same thing. Feminists have responded by saying that female sexual abuse is fundamentally different from male, less dangerous to society, less hurtful to its victims.

While I was doing research for this essay, I happened upon a recent podcast discussion between Louise Perry, British author of The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, and Meghan Murphy, Canadian Substack author and editor of Feminist Current. The podcast was called “What Happened to Feminism?” and I tuned in because I have enjoyed their perspectives on other issues.

Perry and Murphy are both critics of feminism who remain, as their conversation confirmed, staunchly feminist and anti-male. At one point in the podcast (at about 50:00), the conversation turned to #MeToo, and especially to allegations against teachers. Having already agreed that 95% of MeToo allegations were true, or at least based on something real, the pundits went on to agree, with disconcerting laughter, that there was no comparison between a “crazy” woman who “had sex” with a male student in her class, and a “dangerous” man, a “predatory rapist”, who went after under-age girls in his power.

Murphy even trotted out the old chestnut that abused boys were “stoked about the situation” in getting with “the hot teacher”. After all, she chuckled, “Men are gross predators. Men are perverts. They can’t keep it in their pants.” Perry, seeming taken aback by Murphy’s vulgarity, nonetheless agreed that the sexual abuse of boys is in an entirely different category from that of girls: “It is so annoying to me,” she said, “when people will go around claiming that these are exactly the same”.

Indifference to the victimization of boys, and lack of shame in admitting it, could hardly have been more stark. I mention the podcast not because it was singularly outrageous but because the attitudes expressed in it are still so much the norm, even amongst women who claim to have rethought other feminist beliefs.

Fireside Chat – Winter War

World War Two

Published 15 Mar 2025Anna sits down to quiz Indy and Sparty about the Winter War! Did Simo Hayha really kill 500 men? Who’s to blame for the Soviet farce? And what was the Sausage War?

(more…)

Sir Wilfred Laurier is apparently the next designated target for the decolonialization mobs

Having run out of ways to desecrate the memory of our founding prime minister, the shrieking harpies seem to have designated the best Liberal prime minister in Canadian history to be unpersoned this time:

The so-called “Laurier Legacy Project” began in 2022 when the eponymous post-secondary institution in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario, decided to conduct a “scholarly examination of the legacy and times” of Canada’s seventh prime minister (1896-1911). The academic investigation was launched in the wake of the murder of George Floyd in the U.S. and the suspected but unconfirmed discovery of unknown graves near the site of a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C. Institutions were facing pressure to publicly demonstrate they were taking immediate action against colonial legacies.

But was the school really committed to “conducting a scholarly examination” of Laurier? One that would weigh evidence, consider context, and arrive at a conclusion? Spoiler alert: of course not.

The university’s own website is a dead giveaway. A page titled “Who was Wilfrid Laurier?” begins with a single paragraph summarizing the former prime minister’s accomplishments, noting his ability to forge compromise, his participation in the construction of a second transcontinental railway, and the addition of two provinces, Saskatchewan and Alberta.

The rest of the answer to the question “Who is Wilfrid Laurier?” is four negative paragraphs detailing his record on Indigenous relations, restrictive immigration policies, and his role in “actively support[ing] the expansion of British imperialism on the African continent through his involvement in the South African War”. The page offers no hint of balance or objectivity. Perhaps this is what we have come to expect when institutions engage in historical investigations: the judgement has already been made. It’s just the path to get there that remains.

While the Laurier Legacy Project began in 2022, it is relevant today because the university quietly published its conclusion last fall. The report, written by post-doctoral fellow Katelyn Arac, called for 17 recommendations, most of which relate to the university and its extensive DEI policies. These included creating scholarships for communities “marginalized by Laurier” as well as building “artistic displays … in equity-deserving communities”. But few of the recommendations had to do with the actual legacy of the former prime minister.

Much like the school’s website, however, the language of the report made its bias known. Dr. Arac admitted her focus was on policy decisions related to “immigration and relations with Indigenous peoples”. She went on: “These policies were designed with two objectives in mind — assimilation and/or erasure; in other words, the eradication of Indigenous peoples in the land we now call Canada through policies of settler-colonialism”.

The report is part of an unfortunate trend in history today: measuring historical figures by a process of selective evidence. Rather than look objectively at the legacy of Canada’s first francophone prime minister, the project set out to investigate only where Laurier could be seen to have failed. And there were failures. That is part of history and governing.

George Hyde’s First Submachine Gun: The Hyde Model 33

Forgotten Weapons

Published 11 Mar 2018George Hyde was a gun designer who is due substantial credit, but whose name is rarely heard, because he did not end up with his name on an iconic firearm. Hyde was a German immigrant to the United States in 1927 who formed the Hyde Arms Company and started designing submachine guns. His first was the Model 33, which we have here today. This quickly evolved into the Model 35, which was tested by Aberdeen Proving Grounds in the summer of 1939. It was found to have a number of significant advantages over the Thompson, but also some durability problems. The problems could probably have been addressed, but Hyde (who had gone from working as shop foreman at Griffin & Howe to later becoming chief designer for GM’s Inland division during WWII) had already moved on to a better iteration. His next design was actually adopted as the M2 to replace the Thompson, but production problems caused it to be cancelled. The M3 Grease Gun was chosen instead, and Hyde had designed that as well. He was also responsible for the design of the clandestine .45 caliber Liberator pistol.

The Hyde Model 33 is a blowback submachine gun which obviously took significant influence from the Thompson — just look at the front grip, barrel ribs, controls, magazine well, and stock design. However, it was simpler, lighter, and less expensive than the Thompson. It fared better than the Thompson in military mud and dust tests, probably in part because of its unusual charging handle, a long rod mounted in the rear cap of the receiver. This was pulled rearward to cycle the bolt, a bit like the AR15 charging handle. Like the AR15, this setup eliminated the need for an open slot in the receiver. Apparently, however, the handle had a disconcerting habit of bouncing back into the face of the shooter when firing.

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

QotD: The “Social Contract”

… that’s a problem for modern political science, because — put briefly but not unfairly — all modern political science rests on the idea of the Social Contract, which is false. And not just contingently false, either — it didn’t get overtaken by events or anything like that. It’s false ab initio, because it rests on false premises. It seemed true enough — true enough to serve as the basis of what was once the least-worst government in the history of the human race — but the truth is great and shall prevail a bit, as I think the old saying goes.

Hobbes didn’t actually use the phrase “social contract” in Leviathan, but that’s where his famous “state of nature” argument ends. In the state of nature, Hobbes says, the only “law” is self defense. Every man hath the right to every thing, because nothing is off limits when it comes to self preservation; thus disputes can only be adjudicated by force. And this state of nature will prevail indefinitely, Hobbes says, because even though some men are stronger than others, and some are quicker, cleverer, etc. than others, chance is what it is, and everybody has to sleep sometime — in other words, no man is so secure in so many advantages that he can impose his will on all possible rivals, all the time. We won’t be dragged out of the state of nature by a strongman.

The only way out of the state of nature, Hobbes argues, is for all of us, collectively, to lay down at least some of our rights to a corporate person, the so-called “Leviathan”, who then enforces those rights for us. So far, so familiar, I’m sure, but even if you got all this in a civics class in high school (for the real old fogeys) or a Western Civ class in college (for the rest of us), they probably didn’t go over a few important caveats, to wit:

The phrase corporate person means something very different from what even intelligent modern people think it does, to say nothing of douchebag Leftists. In the highly Latinate English of Hobbes’s day, “to incorporate” meant “to make into a body”, and they used it literally. In Hobbes’s day, you could say that God “incorporated” (or simply “corporated”) Adam from the dust, and nobody would bat an eye. I honestly have no idea what Leftists think the term “corporate person” means — and to be fair, I guess, they seem to have no idea either — but for us, we hear “corporation” and we think in terms of business concerns. Which means we tend to attribute to Hobbes the view that the Leviathan, the corporate person, is an actual flesh and blood person — specifically, the reigning monarch.

That’s wrong. Hobbes was quite clear that the Leviathan could be a senate or something. He thought that was a bad idea, of course — the historical development of English isn’t the only reason we think Hobbes means “the person of the king” when he writes about the Leviathan — but it could be. So long as it’s the ultimate authority, it’s the Leviathan. For convenience, let’s call it “the Leviathan State”, although I hope it’s obvious why Hobbes would consider that redundant.

Second caveat, and the main reason (I suppose) it never occurred to Hobbes to call it a social contract: It can’t be broken. By anyone. Ever. It can be overtaken by events (third caveat, below), but no one can opt out on his own authority. The reason for this is simple: If you don’t permanently lay down your right to self defense (except in limited, Rittenhouse-esque situations that aren’t germane here), then what’s the point? A contract that can be broken at any time, just because you feel like it, is no contract at all. And consider the logical consequences of doing that, from the standpoint of Hobbes’s initial argument: If one of us reverts to the state of nature, then we all do, and the war of all against all begins again.

Third caveat: The Leviathan can be defeated. Hobbes considers international relations a version of the state of nature, one there’s no getting out of. If pressed, he’d probably try to attribute Charles I’s defeat in the English Civil War to outside causes. Indeed at one point he comes perilously close to arguing something very like that New Donatist / “Mandate of Heaven” thing we discussed below, but however it happened, it is unquestionably the case that Charles I’s government is no more. Hobbes bowed to reality — he saw that Parliament actually held the power in England, whatever the theoretical rights and wrongs of it, so even though the physical person of Charles II was there with him in Paris, Hobbes took the Engagement and sailed home.

Severian, “True Conclusions from False Premises”, Founding Questions, 2021-11-22.