Forgotten Weapons

Published Feb 14, 2024The Patchett Machine Carbine Mk I is the predecessor to the Sterling SMG. It was developed by George William Patchett, who was an employee of the Sterling company. At the beginning of the wear, Sterling was making Lanchester SMGs, and Patchett began in 1942 working on a new design that was intended to be simpler, cheaper, and lighter than the Lanchester. He used the receiver tube dimensions from the Sten and the magazine well and barrel shroud from the Lanchester. His first prototypes were ready in 1943, but it wasn’t until early 1944 that the British government actually issued a requirement for a new submachine gun to replace the Stens in service.

The initial Patchett guns worked very well in early 1944 testing, which continued into 1945. It ultimately came out the winner of the trials, but they didn’t conclude until World War Two was over — and nothing was adopted because of the much-reduced need for small arms. Patchett continued to work on the gun, and by 1953 he was able to win adoption of it in the later Sterling form — which is a story for a separate video.

The Patchett was not used in any significant quantity in World War Two. At most, a few of them may have been taken on the parachute drops on Arnhem — there are specifically three trials guns which appear referenced in British documents before Arnhem, but are never mentioned afterwards (numbers 67, 70, and 72). Were they taken into the field? We really don’t know.

(more…)

May 21, 2024

Patchett Machine Carbine Mk I: Sten Becomes Sterling

QotD: First Nations warfare in eastern North America

For this week’s book recommendation, I am going with a recent release, Wayne E. Lee, The Cutting-Off Way: Indigenous Warfare in Eastern North America, 1500-1800 (2023). This is one of those books I have been waiting to come out for quite some time, as I studied under the author at UNC Chapel Hill and so had heard parts of this argument laid out for years; it is a delight to see the whole thing altogether now in one place.

Fundamentally, Lee aims in the book to lay out a complete model for Native American warfare in eastern North America (so the East Coast, but also the Great Lakes region and the Appalachian Mountains), covering both the pre-European-contact system of warfare and also how that system changes as a result of contact. In presenting this model of a “cutting-off” way of war, Lee is explicitly looking to supplant the older scholarly model, called the “skulking way of war”, which he argues has been fatally overtaken by developments in history, archaeology and anthropology. As a description of a whole system of war, Lee discusses tactics, the movement of war parties, logistics and also the strategic aims of this kind of warfare. The book also details change within that model, with chapters covering the mechanisms by which European contact seems to have escalated the violence in an already violent system, the impact of European technologies and finally the way that European powers – particularly the English/British – created, maintained and used relationships with Native American nations (as compared, quite interestingly, to similar strategies of use and control in contemporary English/British occupied Ireland).

The overall model of the “cutting-off” way of war (named because it aimed to “cut off” individual enemy settlements, individuals or raiding parties by surprise or ambush; the phrase was used by contemporary English-language sources describing this form of warfare) is, I think, extremely useful. It is, among other things, one of the main mental models I had in mind when thinking about what I call the “First System” of war.1 Crucially it is not “unconventional” warfare: it has its own well-defined conventions which shape, promote or restrict the escalation of violence in the system. At its core, the “cutting-off” way is a system focused on using surprise, raids and ambushes to inflict damage on an enemy, often with the strategic goal of forcing that enemy group to move further away and thus vindicating a nation’s claim to disputed territory (generally hunting grounds) and their resources, though of course as with any warfare among humans, these basic descriptions become immensely more complicated in practice. Ambushes get spotted and become battles, while enmities that may have begun as territorial disputes (and continue to include those disputes) are also motivated by cycles of revenge strikes, internal politics, diplomatic decisions and so on.

The book itself is remarkably accessible and should pose few problems for the non-specialist reader. Lee establishes a helpful pattern of describing a given activity or interaction (say, raids or the logistics system to support them) by leading with a narrative of a single event (often woven from multiple sources), then following that with a description of the system that event exemplifies, which is turn buttressed with more historical examples. The advantage of those leading spots of narrative is that they serve to ground the more theoretical system in the concrete realia of the historical warfare itself, keeping the whole analysis firmly on the ground. At the same time, Lee has made a conscious decision to employ a fair bit of “modernizing” language: strategy, operations, tactics, logistics, ways, ends, means and so on, in order to de-exoticize Native American warfare. In this case, I think the approach is valuable in letting the reader see through differences in language and idiom to the hard calculations being made and perhaps most importantly to see the very human mix of rationalism and emotion motivating those calculations.

The book also comes with a number of maps, all of which are well-designed to be very readable on the page and a few diagrams. Some of these are just remarkably well chosen: an initial diagram of a pair of model Native American polities, with settlements occupying core zones with hunting-ground peripheries and a territorial dispute between them is in turn followed by maps of the distribution of actual Native American settlements, making the connection between the model and the actual pattern of settlement clear. Good use is also made of period-drawings and maps of fortified Native American settlements, in one case paired with the modern excavation plan. For a kind of warfare that is still more often the subject of popular myth-making than history, this book is extremely valuable and I hope it will find a wide readership.

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, September 29, 2023 (On Academic Hiring)”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-09-29.

1. Itself an ultra-broad category with many exceptions and caveats.

May 20, 2024

At what point did “quiet genocide” become the preferred option for the climate cultists to “save the planet”?

The Daily Sceptic‘s Chris Morrison on the not-so-subtle change in the opinions of the extreme climatistas that getting rid of the majority of the human race is now the preferred way to address their concerns:

The grisly streak of neo-Malthusianism that runs through the green movement reared its ugly head earlier this week when former United Nations contributing author and retired UCL Professor Bill McGuire tweeted that the only “realistic way” to avoid catastrophic climate breakdown was to cull the human population with a high fatality pandemic. The tweet was subsequently withdrawn by McGuire, “not because I regret it”, but people took it the wrong way. McGuire is the alarmists’ alarmist, suggesting for instance that human-caused climate change could lead to more earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The Daily Sceptic will not take his views the wrong way. They are an illuminating insight into environmental Malthusianism that does not get anything like the amount of publicity it deserves.

Every now and then Sir David Attenborough allows the genial TV presenter mask to slip to reveal a harder-edged Malthusian side. Speaking to BBC Breakfast in 2021, he suggested that the Earth would be better off without the human race, describing us as “intruders”. In 2009, Attenborough became the patron of the Optimum Population Trust and told the Guardian: “I’ve never seen a problem that wouldn’t be easier to solve with fewer people.” In 2013, he made the appalling remark that it was “barmy” for the United Nations to send bags of flour to famine-stricken Ethiopia. Too little land, too many people, was his considered judgement.

Any consideration of the refusal of food aid these days brings to mind the 19th century Malthusian Sir Charles Trevelyan, the British civil servant during the Irish famines who saw the starvation as retribution on the local population for their moral failings and tendency to have numerous children. He is said to have seen the great loss of life as a regrettable but unavoidable consequence of reform and regeneration.

Anti-human sentiment is riven through much green thinking. In 2019, Anglia Ruskin University Professor Patricia MacCormack wrote a book suggesting humans were already enslaved to the point of “zombiedom” because of capitalism, and “phasing out reproduction is the only way to repair the damage done to the world”. Green fanatics can be a joyless crowd – it is not enough to declare a climate crisis, now they want a “nookie” emergency. As the economist and philosopher Robert Boulding once remarked: “Is there any more single-minded, simple pleasure than viewing with alarm? At times it is even better than sex.”

The economic distortions of government subsidies

The Canadian federal and provincial governments are no strangers to the (political) attractions of picking winners and losers in the market by providing subsidies to some favoured companies at the expense not only of their competitors but almost always of the economy as a whole, because the subsidies almost never produce the kind of economic return promised. The current British government has also been seduced by the subsidies game, as Tim Congdon writes:

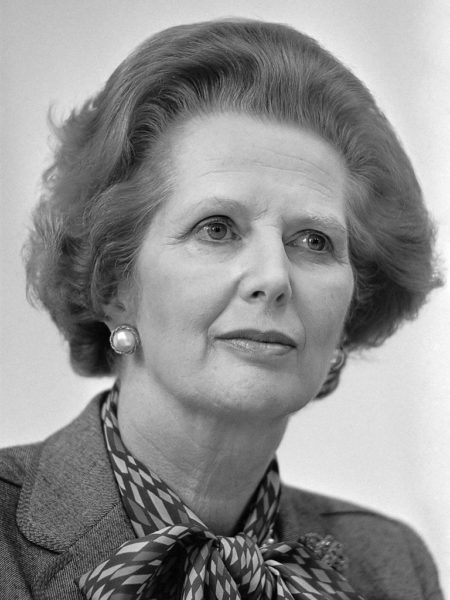

Former British Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1983. She was in office from May 1979 to November 1990.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Why do so many economists support a free market? By the phrase they mean a market, or even an economy dominated by such markets, where the government leaves companies and industries alone, and does not try to interfere by “picking winners” and subsidising them. Two of the economists’ arguments deserve to be highlighted.

The first is about the good use — the productivity — of resources. To earn a decent profit, most companies have to achieve a certain level of output to attract enough customers and to secure high enough revenue per worker.

If the government decides to give money to a favoured group of companies, these companies can survive even if they produce less, and obtain lower revenue per worker, than the others. The subsidisation of a favoured group of companies therefore lowers aggregate productivity relative to a free market situation.

In this column last month I compared the economically successful 1979–97 Conservative government with the economically unsuccessful 2010–2024 Conservative government, which is now coming to an end. In the context it is worth mentioning that Margaret Thatcher and her economic ministers had a strong aversion to government subsidies of any kind.

According to Professor Colin Wren of Newcastle University’s 1996 study, Industrial Subsidies: the UK Experience, subsidies were slashed from £5 billion (in 1980 prices) in 1979 to £0.3 billion in 1990. (In today’s prices that is from £23 billion to under £1.5 billion.)

Thatcher is controversial, and she always will be. All the same, the improvement in manufacturing productivity in the 1980s was faster than before in the post-war period and much higher than it has been since 2010. Further, one of Thatcher’s beliefs was that if the private sector refuses to pursue a supposed commercial opportunity, the public sector most certainly should not try to do so.

Such schemes as HS2 and the Hinkley Point nuclear boondoggle could not have happened in the 1980s or 1990s. They will result in pure social loss into the tens of billions of pounds and will undoubtedly reduce the UK’s productivity.

But there is a second, and also persuasive, general argument against subsidies and government intervention in industry. An attractive feature of a free market policy is its political neutrality. Because market forces are to determine commercial outcomes, businessmen are wasting their time if they lobby ministers and parliamentarians for financial aid.

Honest and straightforward tax-paying companies with British shareholders are rightly furious if they see the government channelling revenues towards other companies who have access to the right politicians and friendly civil servants. By definition, the damage to the UK’s interests is greatest if the recipients of government largesse are foreign.

If King Crimson Played the Batman TV Theme

JB Anderton

Published Jan 8, 2024Batman TV Theme written by Neil Hefti

Arrangement by JB Anderton

Bass, guitar, keyboards and drum loop programming – JB AndertonBatman ’66 is a registered trademark of Greenway Productions/20th Century Fox. No infringement is intended.

#KingCrimson #Batman66

QotD: “Selfless” public servants

WARNING: If you’re an elected government official or if you’re attached to idealistic notions about such officials, do not read this commentary. It will offend you.

Ideally, government in a democratic republic reflects the will of the people, or at least that of the majority. Citizens vote for candidates whom they believe will best promote the general welfare. Victorious candidates, after pledging to uphold the Constitution, go to state capitals or to Washington, D.C., to do The People’s business — to undertake all the good and worthy activities that citizens in their private capacities cannot perform.

Sure, every now and then crooks and demagogues win office, but these are not the norm. Our system of regular, aboveboard democratic elections ensures that officials who do not effectively carry out The People’s business are thrown from office and replaced by more reliable public servants.

Trouble is, it’s not true. It’s a sham. Despite being called “the Honorable”, the typical politician is certainly no more honorable than the typical dentist, auto mechanic, Wal-Mart regional manager or any other private citizen.

Despite being referred to as “public servants”, politicians serve, first and foremost, their own personal political ambitions and they do so by pandering to narrow special interest groups.

Don Boudreaux, “Base Closings”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-03-18.

May 19, 2024

Alexander III of Macedon … usually styled “Alexander the Great”

In the most recent post at A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, Bret Devereaux considers whether the most famous king of Macedon deserves his historic title:

Alexander the Great

Detail from the Alexander Mosaic in the House of the Faun in Pompeii, attributed to the first century BC, via Wikimedia Commons.

I want to discuss his reign with that title, “the Great” (magnus in Latin or μέγας in Greek) stripped off, as Alexander III rather than merely assuming his greatness. In particular, I want to open the question of if Alexander was great and more to the point, if he was, what does that imply about our definitions of greatness?

It is hardly new for Alexander III to be the subject of as much mythology as fact; Alexander’s life was the subject of mythological treatment within living memory. Plutarch (Alex. 46.4) relates an episode where the Greek historian Onesicritus read aloud in the court of Lysimachus – then king of Thrace, but who had been one of Alexander’s somatophylakes (his personal bodyguards, of which there were just seven at at time) – his history of Alexander and in his fourth book reached the apocryphal story of how Alexander met the Queen of the Amazons, Thalestris, at which Lysimachus smiled and asked, “And where was I at the time?” It must have been strange to Lysimachus, who had known Alexander personally, to see his friend and companion become a myth before his eyes.

Then, of course, there are the modern layers of mythology. Alexander is such a well-known figures that it has been, for centuries, the “doing thing” to attribute all manner of profound sounding quotes, sayings and actions to him, functionally none of which are to be found in the ancient sources and most of which, as we’ll see, run quite directly counter to his actual character as a person.

So, much as we set out to de-mystify Cleopatra last year, this year I want to set out – briefly – to de-mystify Alexander III of Macedon. Only once we’ve stripped away the mythology and found the man can we then ask that key question: was Alexander truly great and if so, what does that say not about Alexander, but about our own conceptions of greatness?

Because this post has turned out to run rather longer than I expected, I’m going to split into two parts. This week, we’re going to look at some of the history of how Alexander has been viewed – the sources for his life but also the trends in the scholarship from the 1800s to the present – along with assessing Alexander as a military commander. Then we’ll come back next week and look at Alexander as an administrator, leader and king.

[…]

Sources

As always, we are at the mercy of our sources for understanding the reign of Alexander III. As noted above, within Alexander’s own lifetime, the scale of his achievements and impacts prompted the emergence of a mythological telling of his life, a collection of stories we refer to collectively now as the Alexander Romance, which is fascinating as an example of narrative and legend working across a wide range of cultures and languages, but is fundamentally useless as a source of information about Alexander’s life.

That said, we also know that several accounts of Alexander’s life and reign were written during his life and immediately afterwards by people who knew him and had witnessed the events. Alexander, for the first part of his campaign, had a court historian, Callisthenes, who wrote a biography of Alexander which survived his reign (Polybius is aware – and highly critical – of it, Polyb. 12. 17-22), though Callisthenes didn’t: he was implicated (perhaps falsely) in a plot against Alexander and imprisoned, where he died, in 327. Unfortunately, Callisthenes’ history doesn’t survive to the present (and Polybius sure thinks Callisthenes was incompetent in describing military matters in any event).

More promising are histories written by Alexander’s close companions – his hetairoi – who served as Alexander’s guards, elite cavalry striking force, officers and council of war during his campaigns. Three of these wrote significant accounts of Alexander’s campaigns: Aristobulus,1 Alexander’s architect and siege engineer, Nearchus, Alexander’s naval commander, and Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s bodyguards and infantry commanders, who will become Ptolemy I Soter, Pharaoh of Egypt. Of these, Aristobulus and Ptolemy’s works were apparently campaign histories covering the life of Alexander, whereas Nearchus wrote instead of his own voyages by sea down the Indus River, the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf which he called the Indike.

And you are now doubtless thinking, “amazing, three contemporary accounts, that’s awesome!” So I hope you will contain your disappointment when I follow with the inevitable punchline: none of these three works survives. We also know a whole slew of other, less reliable sounding histories (Plutarch lists works by Cleitarchus, Polycleitus, Onesicritus, Antigenes, Ister, Chares, Anticleides, Philo, two different Philips, Hecataeus, and Duris) do not survive either.

So what do we have?

Fundamentally, our knowledge of Alexander the Great is premised on four primary later works who wrote when all of these other sources (particularly Ptolemy and Aristobulus) still survived. These four authors are (in order of date): Diodorus Siculus (writing in the first century BC), Quintus Curtius Rufus (mid-first cent. AD), Plutarch (early second century AD) and Arrian (Lucius Flavius Arrianus, writing in the early second century AD). Of these, Diodorus’ work, the Bibliotheca historica is a “universal history”, which of course means it is a mile wide and only an inch deep, but Book 17, which covers Alexander’s life, is intact and complete. Curtius Rufus’ work survives only incompletely, with substantial gaps in the text, including all of the first two books.

Plutarch’s Life of Alexander survives intact and is the most substantial of his biographies, but it is, like all of his Parallel Lives, relatively brief and also prone to Plutarch’s instinct to bend a story to fit his moralizing aims in writing. Which leaves, somewhat ironically, the last of these main sources, Arrian. Arrian was a Roman citizen of Anatolian extraction who entered the Senate in the 120s and was consul suffectus under Hadrian, probably in 130. He was then a legatus (provincial governor/military commander in Cappadocia, where Dio reports (69.15.1) that he checked an invasion by the Alani (a Steppe people). Arrian’s history, the Anabasis Alexandrou (usually rendered “Campaigns of Alexander”)2 comes across as a fairly serious, no-nonsense effort to compile the best available sources, written by an experienced military man. Which is not to say Arrian is perfect, but his account is generally regarded (correctly, I’d argue) as the most reliable of the bunch, though any serious scholarship on Alexander relies on collating all four sources and comparing them together.

Despite that awkward source tradition, what we have generally leaves us fairly well informed about Alexander’s actions as king. While we’d certainly prefer to have Ptolemy or Aristobolus, the fact that we have four writers all working from a similar source-base is an advantage, as they take different perspectives. Moreover, a lot of the things Alexander did – founding cities, toppling the Achaemenid Empire, failing in any way to prepare for succession – leave big historical or archaeological traces that are easy enough to track.

1. This is as good a place as any to make a note about transliteration. Almost every significant character in Alexander’s narrative has a traditional transliteration into English, typically based on how their name would be spelled in Latin. Thus Aristobulus, instead of the more faithful Aristoboulos (for Ἀριστόβουλος). The trend in Alexander scholarship today is, understandably, to prefer more faithful Greek transliterations, thus rendering Parmenion (rather than Parmenio) or Seleukos (rather than Seleucus). I think, in scholarship, this is a good trend, but since this is a public-facing work, I am going to largely stick to the traditional transliterations, because that’s generally how a reader would subsequently look up these figures.

2. An ἀνάβασις is a “journey up-country”, but what Arrian is invoking here is Xenophon’s account of his own campaign with the 10,000, the original Anabasis; Arrian seems to have fashioned himself as a “second Xenophon” in a number of ways.

Kamikazes versus Admirals! – WW2 – Week 299 – May 18, 1945

World War Two

Published 18 May 2024The kamikaze menace continues unabated, with suicide flyers hitting not one but two admirals’ flagships. There’s plenty of fighting on land, though, as the Americans advance on Okinawa and take a dam on Luzon to try and solve the Manila water crisis, but even after last week’s German surrender there is also still scattered fighting in Europe.

Chapters

01:34 The Battle of Poljana

06:32 American Advances on Okinawa

10:37 Kamikazes Versus the Admirals

13:58 The Battle for Ipo Dam

19:39 Soldiers Must Go From Europe to the Pacific

23:16 Summary

23:38 Conclusion

25:50 Call to Action

(more…)

“Alcibiades … would surely have spawned numerous Hollywood movies and novelistic treatments, had his name not been so long and complicated”

In The Critic, Armand D’Angour outlines the fascinating career of one of the great “characters” of ancient Greece, Alcibiades:

“Drunken Alcibiades interrupting the Symposium”, an engraving from 1648 by Pietro Testa (1611-1650)

Via Wikimedia Commons.

The career of the aristocratic Athenian politician, lover, general and traitor Alcibiades (c. 451–404 BC) is so well documented and colourful that it would surely have spawned numerous Hollywood movies and novelistic treatments, had his name not been so long and complicated (the standard English pronunciation is Al-si-BUY-a-deez).

His popularity, duplicity and unwavering self-regard make for ready points of comparison with modern politicians. The sheer amount of historical detail attached to his story is reflected in Aristotle’s comment in his Poetics: “Poetry is more scientific and serious than history, because it offers general truths whilst history gives particular facts … A ‘particular fact’ is what Alcibiades did or what was done to him.”

We know about “what Alcibiades did and what was done to him” from several authoritative ancient writers. The most entertaining portrayal, however, is that of the philosopher Plato (c. 425–347 BC), whose dialogue Symposium relates how Alcibiades gatecrashed a party at the home of the playwright Agathon, where several speeches had already been delivered on the theme of eros (love):

Suddenly there was a loud banging on the door, and the voices of a group of revellers could be heard outside along with that of a piper-girl. Agathon told his servants to investigate: “If they’re friends, invite them in,” he said.” If not, tell them the party’s over.” A little later they heard the voice of Alcibiades echoing in the courtyard. He was thoroughly drunk, and kept booming “Where’s Agathon? Take me to Agathon.” Eventually he appeared in the doorway, supported by a piper-girl and some servants. He was crowned by a massive garland of ivy and violets, and his head was flowing with ribbons. “Greetings, friends,” he said, “will you permit a very drunken man to join your party?”

Alcibiades proceeds to eulogise the wisdom and fortitude of his beloved mentor, the philosopher Socrates, detailing how the latter saved his life in a battle in Northern Greece in 432 BC at the start of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, a conflict that dragged on until Athens’ defeat in 404 BC.

The prominence of Alcibiades in Platonic writings stems from his long and close relationship with Plato’s teacher Socrates. He was born in Athens to aristocratic forebears and at around the age of four lost his father Clinias, who was killed in battle in 447 BC. Along with his brother, Alcibiades entered the guardianship of Pericles, his mother’s cousin and Athens’ leading politician.

Shortly afterwards, Pericles was to take Aspasia of Miletus, a clever woman admired by Socrates, as his partner. Aspasia’s sister was married to Alcibiades the Elder, Clinias’ father, so Aspasia was Alcibiades’ great-aunt by marriage. Her acquaintance with Socrates might have been what led Pericles to appoint Socrates as a mentor for his young ward.

As a teenager Alcibiades was widely admired for his good looks and spirited personality, but he was also notorious for misdemeanours, such as when he struck a teacher for dishonouring Homer, released a bird into the Council chamber to disrupt proceedings, and paraded his dog in public with its tail docked.

Ambitious Athenians were expected to espouse a “love of honour” (philotimia), and Alcibiades displayed this to extremes. He married the daughter of a wealthy Athenian, and when she tried to divorce him because of his affairs, he lifted her bodily and carried her home through the crowded Agora.

Rush Meets LOONEY TUNES???

pdbass

Published Jan 4, 2024Remember that time Rush worked music from cartoons into one of their greatest recordings?

Digging into “La Villa Strangiato” from 1978’s Hemispheres, breaking down Geddy Lee’s wicked bass solo (and its Jazz connections) and showing you how pianist/composer Raymond Scott will always be linked to this iconic prog rock instrumental.

(more…)

QotD: Taxation and theft

High-income earners pay a higher rate of tax than people on low incomes. So why is it unfair, as Kim Beazley argues, that high-income earners receive a larger tax cut?

An analogy: your house and your neighbour’s house are both burgled. You lose a television. He loses a DVD player, microwave, his collection of Chomsky memorabilia (it’s an inner-city house), and a unique framed Leunig depicting Mr Curly’s pedophilia arrest. Would it be unfair if police were to return all of this fellow’s belongings, and you were only to get back your 24-inch Sony?

Tim Blair, “Simplistic right-wing greed justification attempted”, Road to Surfdom, 2005-05-12.

[H/T to Samizdata, both for the link and for their title on the post, which I’ve purloined.]

May 18, 2024

The plight of Greek refugees after the Greco-Turkish War

As part of a larger look at population transfers in the Middle East, Ed West briefly explains the tragic situation after the Turkish defeat of the Greek invasion into the former Ottoman homeland in Anatolia:

“Greek dialects of Asia Minor prior to the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Evolution of Greek dialects from the late Byzantine Empire through to the early 20th century leading to Demotic in yellow, Pontic in orange, and Cappadocian in green. Green dots indicate Cappadocian Greek speaking villages in 1910.”

Map created by Ivanchay via Wikimedia Commons.

While I understand why people are upset by the Nakba, and by the conditions of Palestinians since 1948, or particular Israeli acts of violence, I find it harder to understand why people frame it as one of colonial settlement. The counter is not so much that Palestine was 2,000 years ago the historic Jewish homeland – which is, to put it mildly, a weak argument – but that the exodus of Arabs from the Holy Land was matched by a similar number of Jews from neighbouring Arab countries. This completely ignored aspect of the story complicates things in a way in which some westerners, well-trained in particular schools of thought, find almost incomprehensible.

The 20th century was a period of mass exodus, most of it non-voluntary. Across the former Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires the growth in national consciousness and the demands for self-determination resulted in enormous and traumatic population transfers, which in Europe reached its climax at the end of the Second World War.

Although the bulk of this was directed at Germans, the aggressors in the conflict, they were not the only victims – huge numbers of Poles were forcibly moved out of the east of the country to be resettled in what had previously been Germany. The entire Polish community in Lwów, as they called it, was moved to Wrocław, formerly Breslau.

Maps of central and eastern Europe in the 19th century would have shown a confusing array of villages speaking a variety of languages and following different religions, many of whom wouldn’t have been aware of themselves as Poles, Romanians, Serbs or whatever. These communities had uneasily co-existed under imperial rulers until the spread of newspapers and telegraph poles began to form a new national consciousness, usually driven by urban intellectuals LARPing in peasant fantasies.

This lack of national consciousness was especially true of the people who came to be known as Turks; the Balkans in the late 19th century had a huge Muslim population, most of whom were subsequently driven out by nationalists of various kinds. Many not only did not see themselves as Turks but didn’t even speak Turkish; their ancestors had simply been Greeks or Bulgarians who had adopted the religion of the ruling power, as many people do. Crete had been one-third Muslim before they were pushed out by Greek nationalists and came to settle in the Ottoman Empire, which is why there is still today a Greek-speaking Muslim town in Syria.

This population transfer went both ways, and when that long-simmering hatred reached its climax after the First World War, the Greeks came off much worse. Half a million “Turks” moved east, but one million Greek speakers were forced to settle in Greece, causing a huge humanitarian crisis at the time, with many dying of disease or hunger.

That population transfer was skewed simply because Atatürk’s army won the Greco-Turkish War, and Britain was too tired to help its traditional allies and have another crack at Johnny Turk, who – as it turned out at Gallipoli – were pretty good at fighting.

The Greeks who settled in their new country were quite distinctive to those already living there. The Pontic Greeks of eastern Anatolia, who had inhabited the region since the early first millennium BC, had a distinct culture and dialect, as did the Cappadocian Greeks. Anthropologically, one might even have seen them as distinctive ethnic groups altogether, yet they had no choice but to resettle in their new homeland and lose their identity and traditions. The largest number settled in Macedonia, where they formed a slight majority of that region, with many also moving to Athens.

The loss of their ancient homelands was a bitter blow to the Greek psyche, perhaps none more so than the permanent loss of the Queen of Cities itself, Constantinople. This great metropolis, despite four and a half centuries of Ottoman rule, still had a Greek majority until the start of the 20th century but would become ethnically cleansed in the decades following, the last exodus occurring in the 1950s with the Istanbul pogroms. Once a mightily cosmopolitan city, Istanbul today is one of the least diverse major centres in Europe, part of a pattern of growing homogeneity that has been repeated across the Middle East.

But the Greek experience is not unique. Imperial Constantinople was also home to a large Jewish community, many of whom had arrived in the Ottoman Empire following persecution in Spain and other western countries. Many spoke Ladino, or Judeo-Spanish, a Latinate language native to Iberia. Like the Greeks and Armenians, the Jews prospered under the Ottomans and became what Amy Chua called a “market-dominant minority”, the groups who often flourish within empires but who become most vulnerable with the rise of nationalism.

And with the growing Turkish national consciousness and the creation of a Turkish republic from 1923, things got worse for them. Turkish nationalists and their allies murdered vast numbers of Armenians, Greeks and Assyrian Christians in the 1910s, and the atmosphere for Jews became increasingly tense too, with more frequent outbursts of communal violence. After the First World War, many began emigrating to Palestine, now under British control and similarly spiralling towards violence caused by demographic instability.

Glory Days of the Kamikaze! – Operation Kikusui

World War Two

Published 17 May 2024During the Battle of Okinawa, the Japanese see the opportunity to cripple the core of the Allied navies. With their conventional air and naval forces unable to challenge the Allies, the Japanese unleash a wave of mass Kamikaze attacks. Hundreds of suicide pilots smash their aircraft into the Allied fleet. This is Operation Kikusui.

(more…)