World War Two

Published 17 Jan 2025This episode of Out of the Foxholes dives deep into your WWII questions. From LGBTQ+ persecution during and after the war, to the potential impact of diverting Battle of the Bulge troops to the Eastern Front, and Ukrainian collaboration with the Germans, we unravel the complexities of war. Join us as we tackle the secrets, strategies, and untold stories of WWII.

(more…)

January 18, 2025

The Battle of the Bulge, LGBTQ+ Victims & Atomic Secrets – WW2 – OOTF 038

Incentives matter even to “objective” scientists

A 2019 Canadian “study” ideally illustrates that scientists are just as human as anyone else where they are incentivized to provide “desired” outcomes:

“The Beer Store” by Like_the_Grand_Canyon is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Earlier this year, a major Canadian study on alcohol policy provided an excellent illustration of this. As news headlines across the country reported, 16 scientists and researchers at various universities and institutions had, through their Canadian Alcohol Policy Evaluation, shown that provincial governments are “failing to address alcohol problems”.

The scientists evaluated provincial government policies and assigned a grade in the “D” range to seven of Canada’s 13 provinces or territories, while five received an “F”. The policy evaluation, however, was a curious one. Strangely, the policy evaluation did not evaluate whether government policies were beneficial to those who want to buy or sell alcohol.

Instead, provincial governments were evaluated more favorably if they devoted greater efforts toward afflicting buyers and sellers of alcohol through punitive taxes, price controls, heavy restrictions on the sale and marketing of alcoholic beverages, higher minimum legal drinking ages, and so on.

Even in the most restrictive markets, the researchers found that alcohol was too cheap, or that its purchase was too convenient, or that governments did not do enough to discourage or restrict its sale and consumption.

Predictably, and perhaps exemplifying Berlinski’s point on scientists grasping for government funds, the report authored by 16 scientists whose livelihoods involve raising public alarm about alcohol consumption concluded that there ought to be more government funding for public education on the dangers of alcohol consumption.

The report also advocated more government funding for bureaucracies to discourage drinking, more government funding for a lead organization to implement restrictive alcohol policies, more government funding for independent monitoring of such implementation, and more government funding to track and report the harm caused by alcohol consumption.

Like the CEO of a domestic automobile company insisting that tariffs against car imports — which would cause a massive wealth redistribution from consumers’ wallets into his own and those of the company’s shareholders — are in the national interest, the anti-drinking scientists insisted in the name of public health and wellness upon income redistribution from taxpayers and consumers to their own industry.

Is the World Really Running Out of Sand?

Practical Engineering

Published 1 Oct 2024Sand: a treatise …

There’s a lot changing in the construction industry, and a lot of growth in the need for materials like sand and gravel. But I don’t think it’s fair to say the world is running out of those materials. We’re just more aware of all the costs involved in procuring them, and hopefully taking more account for how they affect our future and the environment.

(more…)

QotD: On Auguste Rodin’s Fallen Caryatid

“For three thousand years architects designed buildings with columns shaped as female figures. At last Rodin pointed out that this was work too heavy for a girl. He didn’t say, ‘Look, you jerks, if you must do this, make it a brawny male figure’. No, he showed it. This poor little caryatid has fallen under the load. She’s a good girl — look at her face. Serious, unhappy at her failure, not blaming anyone, not even the gods … and still trying to shoulder her load, after she’s crumpled under it.

“But she’s more than good art denouncing bad art; she’s a symbol for every woman who ever shouldered a load too heavy. But not alone women — this symbol means every man and woman who ever sweated out life in uncomplaining fortitude, until they crumpled under their loads. It’s courage, […] and victory.”

“‘Victory’?”

“Victory in defeat; there is none higher. She didn’t give up […] she’s still trying to lift that stone after it has crushed her. She’s a father working while cancer eats away his insides, to bring home one more pay check. She’s a twelve-year old trying to mother her brothers and sisters because Mama had to go to Heaven. She’s a switchboard operator sticking to her post while smoke chokes her and fire cuts off her escape. She’s all the unsung heroes who couldn’t make it but never quit.

Robert A. Heinlein, Stranger in a Strange Land, 1961.

January 17, 2025

“… most of them can do simple low-IQ jobs like manual labor, basic retail, or writing for the New York Times“

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander discusses the highly controversial national IQ estimates of Richard Lynn … I’m sure I don’t need to spell out exactly why they were (and continue to be) controversial:

Lynn’s national IQ estimates (source)

Richard Lynn was a scientist who infamously tried to estimate the average IQ of every country. Typical of his results is this paper, which ranged from 60 (Malawi) to 108 (Singapore).

People obviously objected to this, and Lynn spent his life embroiled in controversy, with activists constantly trying to get him canceled/fired and his papers retracted/condemned. His opponents pointed out both his personal racist opinions/activities and his somewhat opportunistic methodology. Nobody does high-quality IQ tests on the entire population of Malawi; to get his numbers, Lynn would often find some IQ-ish test given to some unrepresentative sample of some group related to Malawians and try his best to extrapolate from there. How well this worked remains hotly debated; the latest volley is Aporia‘s Are Richard Lynn’s National IQ Estimates Flawed? (they say no).

I’ve followed the technical/methodological debate for a while, but I think the strongest emotions here come from two deeper worries people have about the data:

First, isn’t it horribly racist to say that people in sub-Saharan African countries have IQs that would qualify as an intellectual disability anywhere else?

Second, isn’t it preposterous and against common sense to compare sub-Saharan Africans to the intellectually disabled? You can talk to a Malawian person, and talk to a person with Down’s Syndrome, and the former is obviously much brighter and more functional than the latter. Doesn’t that mean that the estimates have to be wrong?

But both of these have simple answers, which IMHO defuse the worrying nature of Lynn’s results. These answers aren’t original to me, but as far as I know, nobody has put them together in one place before. Going over each in turn:

1: Isn’t It Super-Racist To Say That People In Sub-Saharan African Countries Have IQs Equivalent To Intellectually Disabled People?

No. In fact, it would be super-racist not to say this! We shouldn’t conflate advocacy with science. But if we did, Lynn’s position would make better anti-racist advocacy than his detractors’.

The “racist” position is that all IQ differences between groups are genetic. The “anti-racist” position is that they’re a product of environment — things like nutrition, health care, and education.

We know that in the US, where we do give people good IQ tests, whites average IQ 100 and blacks average IQ 85.

If IQ was 100% genetic, we should expect Africans to have an IQ of 85, since American and African blacks have similar genes. This isn’t exactly right — US blacks have some intermixing with whites, and only some of Africa’s staggering diversity reached the US — but it’s close enough.

Trump’s demands include some things that would be quite beneficial to Canada

In the National Post, Bryan Schwartz suggests that some of the things Trump has raised as issues in Canada/US trade would be economically sensible for Canada to address because they’d reduce costs of doing business in Canada which would be good for all Canadians (except the crony capitalists in the blatantly protectionist “supply management” cartels):

US President-elect Donald Trump trolling about Canada becoming the 51st state of the union does seem to have directed attention to our bilateral trade situation wonderfully.

The threatened Trump tariffs would hurt both the United States and Canada in many ways. But the U.S., with a larger and more productive economy (on a per capita basis), is better able to sustain the immediate pain. The economic pressure on Canada is, therefore, serious and credible.

Canada should first address issues that are of particular importance to the Trump administration. The incoming president tends to emphasize national security, even over economic nationalism. The authority of the president, under the inherent powers of the office and congressional statutes, is greater if the issue relates to national security.

The same holds under international trade agreements. The president can raise issues that Canada can address in a prompt and reasonable manner. These include border security and increasing Canada’s commitment to contributing its fair share to international alliances, which would include increasing military expenditures.

Second, Canada should recognize that external pressures can provide opportunities to do things that are in this country’s own interests, but are otherwise politically difficult. Outside pressures have in the past encouraged Canada to adopt several measures that are good for the country, such as reducing pork-barreling and regional favouritism in government contracting.

Canada’s dairy protectionism provides a good example of a trade concession that would benefit Canada, as it is unfair to lower-income Canadians and, in the long run, hurts the industry itself. An industry more exposed to competitive pressures would be incentivized to be more productive and seek to expand into international markets.

Australia has shown how such marketing boards can be abolished in a manner that gives some time to the industry to adjust and ultimately benefits all concerned. Canada could similarly rid itself of its outdated and counterproductive Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation, as well. To the extent that the United States pressures us to eliminate such supply management systems, it is actually doing us a favour.

Likewise, given that the U.S. is moving away from suppressing free expression in cyberspace, Canada would benefit from joining such initiatives rather than continuing down the path of having government or big companies effectively engage in censorship under the guise of fighting “disinformation”. The best remedy for any wrongheaded speech is rightheaded speech, not censorship.

At Dominion Review, Brian Graff steals a line from George C. Scott’s portrayal of Patton who said (in the film, not in real life) – “Rommel, you magnificent bastard. I read your book!” after reading the book of Trump’s Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer:

Lighthizer wrote a book (released in June 2023) about his trade views and experience entitled No Trade Is Free: Changing Course, Taking on China, and Helping America’s Workers, which I just read. I only became aware of Lighthizer in November, in part because of a review of his book in The Guardian.

I don’t think Lighthizer is a bastard (literally or figuratively). He is hardly magnificent, but his book should be required reading for Canadians interested in our upcoming negotiations with the US. Our government would learn how best to counter the US by preparing a strong strategy and going on offence even before negotiations begin.

In short, we should not give away anything for free. This is Lighthizer’s position in matters of trade. For example, Canada should not volunteer to meet the two percent defense spending target ahead of negotiations. If anything, Canada should be accusing the US of whatever complaints we can muster. Trump might complain about the Canadian border being porous when it comes to people and drugs, but we can make the same claims, and add on the fact that the US should do more to stop the flow of illegal guns into Canada across our southern border.

Lighthizer provides a history of the US based around the idea that the US revolution and the constitution were a reaction to the mercantilist policies of Britain, which wanted to export manufactured goods and import only raw materials, while also limiting US trade with the rest of the world. Here is Lighthizer’s essential view:

Today, the tide has turned against the argument for unfettered free trade, in no small part because of the changes we made in the Trump administration. More broadly, evidence and experience have shown us that free trade is a unicorn – a figment of the Anglo-American imagination. No one really believes in it outside of countries in the Anglo-American world, and no one practices it. After the lessons of the past couple decades or so, few believe in it even within that world, save for some hard-core ideologues. It is a theory that never worked anywhere.

This is his critique of the neoliberal free trade approach:

According to the definitions preferred by these efficiency-minded free traders, the downside of trade for American producers is not evidence against their approach but rather is an unfortunate but necessary side effect. That’s because free trade is always taken as a given, not as an approach to be questioned. Rather than envisioning the type of society desired and then, in light of that conception of the common good, fashioning a trade policy to fit that vision, economists tend to do the opposite: they start from the proposition that free trade should reign and then argue that society should adapt. Most acknowledge that lowering trade barriers causes economic disruption, but very few suggest that the rules of trade should be calibrated to help society better manage those effects. On the right, libertarians deny that these bad effects are a problem, because the benefits of cheap consumer goods for the masses supposedly outweigh the costs, and factory workers, in their view, can be retrained to write computer programs. On the left, progressives promote trade adjustment assistance and other wealth-transfer schemes as a means of smoothing globalization’s rough edges.

This section is also key:

… mercantilism and a free market are dramatically different systems, with distinctions that are important to note. Mercantilism is a school of nationalistic political economy that emphasizes the role of government intervention, trade barriers, and export promotion in building a wealthy, powerful state. The term was popularized by Adam Smith, who described the policies of western European colonial powers as a “mercantile system.” Then and now, there are a vast array of tools available for countries seeking to go down this path. Mercantilist governments, for instance, frequently employ import substitution policies that support exports and discourage imports in order to accumulate wealth. They employ tariffs, too, of course, and they limit market access, employ licensing schemes, and use government procurement, subsidies, SOEs, and manipulation of regulation to favor domestic industries over foreign ones.

The focus of the book, and the main villain, is China, followed closely by the World Trade Organization (WTO). Canada gets less than 77 mentions, Mexico gets 99 mentions in the first 352 pages of 576 (the e-book stops counting at 99), and Japan gets 99 mentions in the first 400 pages. Compare this to China, which gets 99 mentions within the first 101 pages alone.

Schwarzlose 1898 Semiauto Pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 4 May 2015The model 1898 Schwarzlose was a self loading pistol definitely ahead of its time. It was simple, powerful (for the period; it was chambered for 7.63mm Mauser), and remarkably ergonomic. It used a short recoil, rotating bolt mechanism to operate, and very cleverly had one single spring which did the duties of primary recoil spring, striker spring, trigger spring, and extractor spring. Why it failed to become a commercial success is a question I have not been able to definitively answer — I suspect it must have been due to cost. Edward Ezell theorizes that it was unable to compete with the Borchardt/Luger and Mauser pistols because those were able to be made with much more economy of scale. It is really a shame, because the Schwarzlose 1898 is the best of all the pre-1900 handguns I have encountered.

QotD: Foraging for supplies in pre-modern armies

We should start with the sort of supplies our army is going to need. The Romans neatly divided these into four categories: food, fodder, firewood and water each with its own gathering activities (called by the Romans frumentatio, pabulatio, lignatio and aquatio respectively; on this note Roth op. cit. 118-140), though gathering food and fodder would be combined whenever possible. That’s a handy division and also a good reflection of the supply needs of armies well into the gunpowder era. We can start with the three relatively more simple supplies, all of which were daily concerns but also tended to be generally abundant in areas that armies were.

For most armies in most conditions, water was available in sufficient quantities along the direction of march via naturally occurring bodies of water (springs, rivers, creeks, etc.). Water could still be an important consideration even where there was enough to march through, particularly in determining the best spot for a camp or in denying an enemy access to local water supplies (such as, famously at the Battle of Hattin (1187)). And detailing parties of soldiers to replenish water supplies was a standard background activity of warfare; the Romans called this process aquatio and soldiers so detailed were aquatores (not a permanent job, to be clear, just regular soldiers for the moment sent to get water), though generally an army could simply refill its canteens as it passed naturally occurring watercourses. Well organized armies could also dig wells or use cisterns to pre-position water supplies, but this was rarely done because it was tremendously labor intensive; an army demanded so much water that many wells would be necessary to allow the army to water itself rapidly enough (the issue is throughput, not well capacity – you can only lift so many buckets of so much water in an hour in a single well). For the most part armies confined their movements to areas where water was naturally available, managing, at most, short hops through areas where it was scarce. If there was no readily available water in an area, agrarian armies simply couldn’t go there most of the time.

Like water, firewood was typically a daily concern. In the Roman army this meant parties of firewood forages (lignatores) were sent out regularly to whatever local timber was available. Fortunately, local firewood tended to be available in most areas because of the way the agrarian economy shaped the countryside, with stretches of forest separating settlements or tended trees for firewood near towns. Since an army isn’t trying to engage in sustainable arboriculture, it doesn’t usually need to worry about depleting local wood stocks. Moreover, for our pre-industrial army, they needn’t be picky about the timber for firewood (as opposed to timber for construction). Like water gathering, collecting firewood tends to crop up in our sources when conditions make it unusually difficult – such as if an army is forced to remain in one place (often for a siege) and consequently depletes the local supply (e.g. Liv. 36.22.10) or when the presence of enemies made getting firewood difficult without using escorts or larger parties (e.g. Ps.-Caes. BAfr. 10). Sieges could be especially tricky in this regard because they add a lot of additional timber demand for building siege engines and works; smart defenders might intentionally try to remove local timber or wood structures to deny an approaching army as part of a scorched earth strategy (e.g. Antioch in 1097). That said apart from sieges firewood availability, like water availability is mostly a question of where an army can go; generals simply long stay in areas where gathering firewood would be impossible.

Then comes fodder for the animals. An army’s animals needed a mix of both green fodder (grass, hay) and dry fodder (barley, oats). Animals could meet their green fodder requirements by grazing at the cost of losing marching time, or the army could collect green fodder as it foraged for food and dry fodder. As you may recall, cut grain stalks can be used as green fodder and so even an army that cannot process grains in the fields can still quite easily use them to feed the animals, alongside barley and oats pillaged from farm storehouses. The Romans seem to have preferred gathering their fodder from the fields rather than requisitioning it from farmers directly (Caes. BG 7.14.4) but would do either in a pinch. What is clear is that much like gathering water or firewood this was a regular task a commander had to allot and also that it often had to be done under guard to secure against attacks from enemies (thus you need one group of soldiers foraging and another group in fighting trim ready to drive off an attack). Fodder could also be stockpiled when needed, which was normally for siege operations where an army’s vast stock of animals might deplete local grass stocks while the army remained encamped there. Crucially, unlike water and firewood, both forms of fodder were seasonal: green fodder came in with the grasses in early spring and dry fodder consists of agricultural products typically harvested in mid-summer (barley) or late spring (oats).

All of which at last brings us to the food, by which we mostly mean grains. Sources discussing army foraging tend to be heavily focused on food and we’ll quickly see why: it was the most difficult and complex part of foraging operations in most of the conditions an agrarian army would operate. The first factor that is going to shape foraging operations is grain processing. [S]taple grains (especially wheat, barley and later rye) make up the vast bulk of the calories an army (and it attendant non-combatants) are eating on the march. But, as we’ve discussed in more detail already, grains don’t grow “ready to eat” and require various stages of processing to render them edible. An army’s foraging strategy is going to be heavily impacted by just how much of that processing they are prepared to do internally.

This is one area where the Roman army does appear to have been quite unusual: Roman armies could and regularly did conduct the entire grain processing chain internally. This was relatively rare and required both a lot of coordination and a lot of materiel in the form of tools for each stage of processing. As a brief refresher, grains once ripe first have to be reaped (cut down from the stalks), then threshed (the stalks are beaten to shake out the seeds) and winnowed (the removal of non-edible portions), then potentially hulled (removing the inedible hull of the seed), then milled (ground into a powder, called flour, usually by the grinding actions of large stones), then at last baked into bread or a biscuit or what have you.

It is possible to roast unmilled grain seeds or to boil either those seeds or flour in water to make porridge in order to make them edible, but turning grain into bread (or biscuits or crackers) has significant nutritional advantages (it breaks down some of the plant compounds that human stomachs struggle to digest) and also renders the food a lot tastier, which is good for morale. Consequently, while armies will roast grains or just make lots of porridge in extremis, they want to be securing a consistent supply of bread. The result is that ideally an army wants to be foraging for grain products at a stage where it can manage most or all of the remaining steps to turn those grains into food, ideally into bread.

As mentioned, the Romans could manage the entire processing chain themselves. Roman soldiers had sickles (falces) as part of their standard equipment (Liv. 42.64.2; Josephus BJ 3.95) and so could be deployed directly into the fields (Caes. BG 4.32; Liv. 31.2.8, 34.26.8) to reap the grain themselves. It would then be transported into the fortified camp the Romans built every time the army stopped for the night and threshed by Roman soldiers in the safety of the camp (App. Mac. 27; Liv. 42.64.2) with tools that, again, were a standard part of Roman equipment. Roman soldiers were then issued threshed grains as part of their rations, which they milled themselves (or made into a porridge called puls) using “handmills”. These were not small devices, but roughly 27kg (59.5lbs) hand-turned mills (Marcus Junkelmann reconstructed them quite ably); we generally assume that they were probably carried on the mules on the march, one for each contubernium (tent-group of 6-8; cf. Plut. Ant. 45.4). Getting soldiers to do their own milling was a feat of discipline – this is tough work to do by hand and milling a daily ration would take one of the soldiers of the group around two hours. Roman soldiers then baked their bread either in their own campfires (Hdn 4.7.4-6; Dio Cass. 62.5.5) though generals also sometimes prepared food supplies in advance of operations via what seem to be central bakeries. This level of centralization was part and parcel of the unusual sophistication of Roman logistics; it enabled a greater degree of flexibility for Roman armies.

Greek hoplite armies do not seem generally to have been able to reap, thresh or mill grain on the march (on this see J.W. Lee, op. cit.; there’s also a fantastic chapter on the organization of Greek military food supply by Matthew Sears forthcoming in a Brill Companion volume one of these years – don’t worry, when it appears, you will know!). Xenophon’s Ten Thousand are thus frequently forced to resort to making porridge or roast grains when they cannot forage supplies of already-milled-flour; they try hard to negotiate for markets on their route of march so they can just buy food. Famously the Spartan army, despoiling ripe Athenian fields runs out of supplies (Thuc. 2.23); it’s not clear what sort of supplies were lacking but food and fodder seems the obvious choice, suggesting that the Spartans could at best only incompletely utilize the Athenian grain. All of which contributed to the limited operational endurance of hoplite armies in the absence of friendly communities providing supplies.

Macedonian armies were in rather better shape. Alexander’s soldiers seem to have had handmills (note on this Engels, op. cit.) which already provides a huge advantage over earlier Greek armies. Grain is generally (as noted in our series on it) stored and transported after threshing and winnowing but before milling because this is the form in which has the best balance of longevity and compactness. That means that granaries and storehouses are mostly going to contain threshed and winnowed grains, not flour (nor freshly reaped stalks). An army which can mill can thus plunder central points of food storage and then transport all of that food as grain which is more portable and keeps better than flour or bread.

Early modern armies varied quite a lot in their logistical capabilities. There is a fair bit of evidence for cooking in the camp being done by the women of the campaign community in some armies, but also centralized kitchen messes for each company (Lynn op. cit. 124-126); the role of camp women in food production declines as a product of time but there is also evidence for soldiers being assigned to cooking duties in the 1600s. On the other hand, in the Army of Flanders seems to have relied primarily on external merchants (so sutlers, but also larger scale contractors) to supply the pan de munición ration-bread that the army needed, essentially contracting out the core of the food system. Parker (op. cit. 137) notes the Army of Flanders receiving some 39,000 loaves of bread per day from its contractors on average between April 1678 and February of 1679.

That created all sorts of problems. For one, the quality of the pan de munición was highly variable. Unlike soldiers cooking for themselves or their mess-mates, contractors had every incentive to cut corners and did so. Moreover, much of this contracting was done on credit and when Spanish royal credit failed (as it did in 1557, 1560, 1575, 1596, 1607, 1627, 1647 and 1653, Parker op. cit. 125-7) that could disrupt the entire supply system as contractors suddenly found the debts the crown had run up with them “restructured” (via a “Decree of Bankruptcy”) to the benefit of Spain. And of course that might well lead to thousands of angry, hungry, unpaid men with weapons and military training which in turn led to disasters like the Sack of Antwerp (1576), because without those contractors the army could not handle its logistical needs on its own. It’s also hard not to conclude that this structure increased the overall cost of the Army of Flanders (which was astronomical) because it could never “make the war feed itself” in the words of Cato the Elder (Liv 34.9.12; note that it was rare even for the Romans for a war to “feed itself” entirely through forage, but one could at least defray some costs to the enemy during offensive operations). That said this contractor supplied bread also did not free the Army of Flanders from the need to forage (or even pillage) because – as noted last time – their rations were quite low, leading soldiers to “offset” their low rations with purchase (often using money gained through pillage) or foraging.

Of course added to this are all sorts of food-stuffs that aren’t grain: meat, fruits, vegetables, cheeses, etc. Fortunately an army needs a lot less of these because grains make up the bulk of the calories eaten and even more fortunately these require less processing to be edible. But we should still note their importance because even an army with a secure stockpile of grain may want to forage the surrounding area to get supplies of more perishable foodstuffs to increase food variety and fill in the nutritional gaps of a pure-grain diet. The good news for our army is that the places they are likely to find food (small towns and rural villages) are also likely to be sources of these supplementary foods. By and large that is going to mean that armies on the march measure their supplies and their foraging in grain and then supplement that grain with whatever else they happen to have obtained in the process of getting that grain. Armies in peacetime or permanent bases may have a standard diet, but a wartime army on the march must make do with whatever is available locally.

So that’s what we need: water, fodder, firewood and food; the latter mostly grains with some supplements, but the grain itself probably needs to be in at least a partially processed form (threshed and sometimes also milled), in order to be useful to our army. And we need a lot of all of these things: tons daily. But – and this is important – notice how all of the goods we need (water, firewood, fodder, food) are things that agrarian small farmers also need. This is the crucial advantage of pre-industrial logistics; unlike a modern army which needs lots of things not normally produced or stockpiled by a civilian economy in quantity (artillery shells, high explosives, aviation fuel, etc.), everything our army needs is a staple product or resource of the agricultural economy.

Finally we need to note in addition to this that while we generally speak of “forage” for supplies and “pillage” or “plunder” for armies making off with other valuables, these were almost always connected activities. Soldiers that were foraging would also look for valuables to pillage: someone stealing the bread a family needs to live is not going to think twice about also nicking their dinnerware. Sadly we must also note that very frequently the valuables that soldiers looted were people, either to be sold into slavery, held for ransom, pressed into work for the army, or – and as I said we’re going to be frank about this – abducted for the purpose of sexual assault (or some combination of the above).

And so a rural countryside, populated by farms and farmers is in essence a vast field of resources for an army. How they get them is going to depend on both the army’s organization and capabilities and the status of the local communities.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part II: Foraging”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-07-29.

January 16, 2025

“The only possible conclusion is that we didn’t call them racist often enough”

Apparently there are still a lot of US politicians who think that letting men compete in womens’ sports is not only okay, but praiseworthy:

Of all the absurdities of the culture war, perhaps the most egregious is the normalisation of the idea that men should be able to identify their way into women’s sports. We are living through a period of mania, so we cannot clearly see how this will look to future generations. But I have little doubt that all those photographs of hulking men towering over women on winners’ podiums will be the memes of the future. “Can you believe they let this happen?” they’ll say, scratching their AI-enhanced cyborg heads.

Wherever one stands on Donald Trump, there can be little doubt that his imminent arrival at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue will act as a corrective to this problem. Yesterday, the House of Representatives passed the Protection of Women and Girls in Sports Act with its goal of preventing males who identify as female from participating in school sports. If passed into law, schools that attempt to defy the ban would have their federal funds withheld. The bill was introduced by Republican representative Greg Steube of Florida, and makes clear that it will be a violation of federal law “for a recipient of Federal financial assistance who operates, sponsors, or facilitates an athletic program or activity to permit a person whose sex is male to participate in an athletic program or activity that is designated for women or girls”.

One of the most astonishing aspects of the passing of this bill was the voting outcome. 216 Republicans and only 2 Democrats (Vicente Gonzales and Henry Cueller) voted for the motion. Is it really that controversial that sex, as the bill puts it, “shall be recognized based solely on a person’s reproductive biology and genetics at birth”? You will recall the outcry back in November when Democratic politician Seth Moulton admitted that he objected to mixed-sex contact sports in schools. “I have two little girls,” he said, “I don’t want them getting run over on a playing field by a male or formerly male athlete. But as a Democrat, I’m supposed to be afraid to say that”. For this he was branded a “transphobe” and a “Nazi cooperator”, because we all know that one of the top priorities of the Third Reich was the preservation of women’s rights.

Moulton failed to retain his backbone for the latest vote (he called the bill “too extreme”), but his previous comment had been striking for its honesty. He was willing to openly state that fear was the key factor in the reticence of Democrats on this issue. It cannot be the case that only two Democratic members of the House take the view that there is no advantage in sports conferred by male puberty. Surely most of them must have glanced at a biology textbook from time to time. The charitable conclusion is that they have been browbeaten into voting ideologically, not that they genuinely don’t know that there exist anatomical differences between men and women.

Disturbingly, this vote would seem to suggest that the Democrats are not learning their lessons from the election, and instead are determined to double down on the very attitude that cost them the White House.

The allegations against author Neil Gaiman

I haven’t read the article in question, but it certainly looks ugly if even a few of the allegations turn out to be true:

New York magazine has just published a very long investigative piece on alleged sexual misconduct by the author Neil Gaiman, both contextualizing previously-known allegations and introducing new ones. Writer Lila Shapiro, who clearly did an awful lot of legwork, found several new women who allege various forms of bad sexual behavior against Gaiman. It’s all very serious and disturbing, obviously. I have nothing to contribute and no one cares what I think about such things, so we can leave that story there.

But I’m afraid that Shapiro’s piece does again force me to think about New York‘s story last year about Andrew Huberman. You could be forgiven for thinking “New York‘s SIMILAR story last year about Andrew Huberman,” but this would not be a correct characterization; where Gaiman is accused of many acts that, if true, rise to the level of sexual misconduct, including rape, the Huberman piece contains no such allegations. Huberman is accused of dating multiple women at the same time without the knowledge of all involved, of infidelity generally, and there’s a bizarre fixation on his regular tardiness. It is not a MeTooing piece. And the trouble, I’m afraid, is that the piece was written, edited, packaged, and promoted in a way that inevitably gave audiences the impression that such allegations were included — that Andrew Huberman had been MeToo’d.

The fact that the piece contains no allegations of that type, but seems to have been very deliberately associated by New York, its author Kerry Howley, the magazine’s social media channels, and their many media kaffeeklatsch allies with MeToo stories, was a terrible error in editorial judgment. The Gaiman story helps underline why: this shit is so serious that we can’t afford to play around with these types of narratives. The Rolling Stone University of Virginia gang rape fraternity initiation story, a narrative that fell apart under the barest scrutiny and should never have survived even an amateur journalistic investigation, did a lot of damage in our ongoing efforts to take sexual assault on campus seriously. There’s a higher bar to clear with this stuff for that reason, and the Huberman story utterly failed to clear it.

The story’s presentation in the magazine was draped with innuendo, with as many leading terms and dark implications as can be stuffed in. The image on the cover is styled and colored to make him look sinister. People associated with New York tweeted about the piece as if it was a nuclear bomb, using the kind of language that we’ve grown accustomed to when a MeToo story is published and kills a career. I would argue that the story is deliberately written in the slow-burn reveal style that is typically deployed in MeToo stories — that’s deployed, in fact, in the Gaiman story. (There it makes sense, because the slow burn leads to actual accusations.) At every opportunity, the story exaggerates the implication of a man who, yes, was a shithead to some women he dated. The article is forever presenting quotidian-if-unfortunate behaviors and acting as though we should interpret those behaviors as worthy of the kind of censure that has been brought to bear by men guilty of sexual misconduct in the MeToo era. “I experienced his rage,” says one of Huberman’s exes, suggesting some sort of domestic violence situation, when in fact that’s a reference to a verbal argument — again, maybe unfortunate, but simply not in the world of misconduct.

The magazine’s internal references to the piece, and their social media, played up the usual teasing manner of such publicity, broadly hinting at bad behavior in the realm of sex and romance. The repeated phrase used was “manipulative behavior, deceit, and numerous affairs”. I don’t need to tell you that many people, trained by six-plus years of reading about sexual misconduct, are going to assume that a vast cover story in one of the country’s biggest magazines about a man’s bad behavior and deceit towards his partners is going to be a MeToo story. As many would go on to say, the fanfare and length and publicity about the piece themselves implied that it was a MeTooing. After all, what else would justify that level of attention?

For some unknowable reason, high-tax states keep losing population to low-tax states

“U-Haul Rental Truck (44601958941)” by HireAHelper is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

This probably won’t come as a surprise to many readers, but when people move, they tend to prefer migrating to places where, among other considerations, the taxes are lower than in their old digs. Data from the U.S. government as well as from moving companies reveals that — as we’ve seen in the past — high-tax states are losing residents to states that take a smaller bite out of people’s wallets.

“Americans are continuing to leave high-tax, high-cost-of-living states in favor of lower-tax, lower-cost alternatives. Of the 26 states whose overall state and local tax burdens per capita were below the national average in 2022 (the most recent year of data available), 18 experienced net inbound interstate migration in FY 2024,” Katherine Loughead wrote last week for the Tax Foundation. “Meanwhile, of the 25 states and DC with tax burdens per capita at or above the national average, 17 of those jurisdictions experienced net outbound domestic migration.”

Loughead crunched numbers from both the U.S. Census Bureau as well as U-Haul and United Van Lines. The government data tracks population gains and losses across the country while numbers from the private companies is helpful for comparing flows in and out of various states. The results are revelatory, though not unexpected.

“For the second year in a row, South Carolina saw the greatest population growth attributable to net inbound domestic migration” according to Census Bureau figures. The Tax Foundation separately ranks South Carolina at number 9 for tax burden, with 1 being the lowest tax burden among states and 50 the highest. Rounding out the top-10 population-gainers were Idaho (ranked 29), Delaware (42), North Carolina (23), Tennessee (3), Nevada (18), Alabama (20), Montana (27), Arizona (15), and Arkansas (26).

According to census data, Hawaii lost the biggest share of its population to other states; it’s ranked at 48 for the third-highest tax burden in the country. The rest of the top 10 states for population outflow were New York (50), California (46), Alaska (1), Illinois (44), Massachusetts (37), Louisiana (12), New Jersey (45), Maryland (35), and Mississippi (21).

Numbers released this month by U-Haul and United Van Lines showed migration patterns closely, but not precisely, tracking the Census Bureau’s information. Loughead attributes the disparities, at least in part, to the companies’ varying geographic coverage and market share.

Augustus and the Roman Army – the first emperor and the creation of the professional army

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 7 Aug 2024We take a look at Caesar Augustus, the first emperor (or princeps) of Rome and the great nephew of Julius Caesar. Ancient sources — and Shakespeare and Hollywood — depict him as politician and no soldier in contrast to Mark Antony. How true is this? More importantly, how did the man who created the imperial system and re-shaped society change the Roman army?

This video is based on a talk I gave in 2014 at the Roman Legionary Museum in Caerleon — a museum and adjacent sites, well worth a visit for anyone in or near South Wales.

QotD: “At promise” youth

A new law in California bans the use, in official documents, of the term “at risk” to describe youth identified by social workers, teachers, or the courts as likely to drop out of school, join a gang, or go to jail. Los Angeles assemblyman Reginald B. Jones-Sawyer, who sponsored the legislation, explained that “words matter”. By designating children as “at risk”, he says, “we automatically put them in the school-to-prison pipeline. Many of them, when labeled that, are not able to exceed above that.”

The idea that the term “at risk” assigns outcomes, rather than describes unfortunate possibilities, grants social workers deterministic authority most would be surprised to learn they possess. Contrary to Jones-Sawyer’s characterization of “at risk” as consigning kids to roles as outcasts or losers, the term originated in the 1980s as a less harsh and stigmatizing substitute for “juvenile delinquent”, to describe vulnerable children who seemed to be on the wrong path. The idea of young people at “risk” of social failure buttressed the idea that government services and support could ameliorate or hedge these risks.

Instead of calling vulnerable kids “at risk”, says Jones-Sawyer, “we’re going to call them ‘at-promise’ because they’re the promise of the future”. The replacement term — the only expression now legally permitted in California education and penal codes — has no independent meaning in English. Usually we call people about whom we’re hopeful “promising”. The language of the statute is contradictory and garbled, too. “For purposes of this article, ‘at-promise pupil’ means a pupil enrolled in high school who is at risk of dropping out of school, as indicated by at least three of the following criteria: Past record of irregular attendance … Past record of underachievement … Past record of low motivation or a disinterest in the regular school program.” In other words, “at-promise” kids are underachievers with little interest in school, who are “at risk of dropping out”. Without casting these kids as lost causes, in what sense are they “at promise”, and to what extent does designating them as “at risk” make them so?

This abuse of language is Orwellian in the truest sense, in that it seeks to alter words in order to bring about change that lies beyond the scope of nomenclature. Jones-Sawyer says that the term “at risk” is what places youth in the “school-to-prison pipeline”, as if deviance from norms and failure to thrive in school are contingent on social-service terminology. The logic is backward and obviously naive: if all it took to reform society were new names for things, then we would all be living in utopia.

Seth Barron, “Orwellian Word Games”, City Journal, 2020-02-19.

January 15, 2025

Is there anything climate change can’t do?

Seen on social media earlier this week:

Confirming this, Chris Bray talks about current reporting on the wildfires in and around Los Angeles:

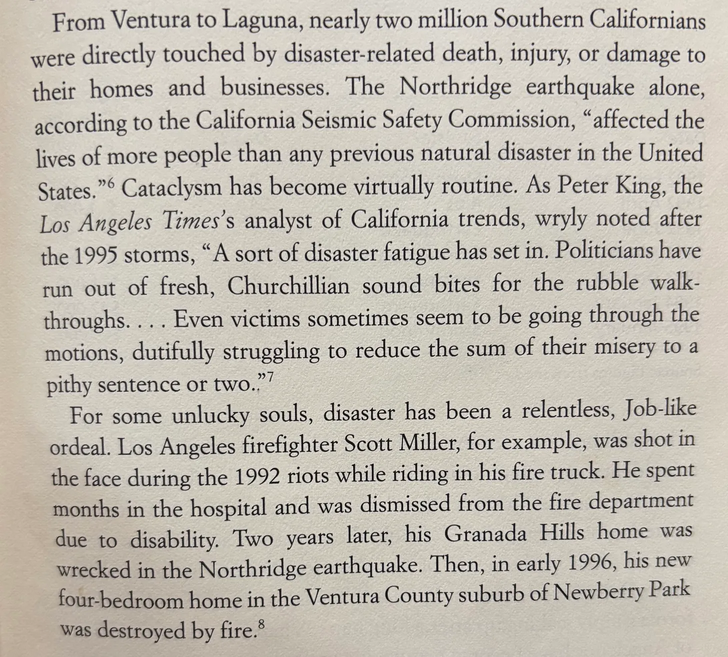

In his much-discussed piece on the Los Angeles fires at the Free Press, Leighton Woodhouse looks to Mike Davis for a narrative foundation. In his book Ecology of Fear, Woodhouse notes, Davis “argued that the area between the beach and the Santa Monica Mountains simply never should have been developed. No matter what measures we take to prevent it, those hills are going to burn, and the houses we erect upon them are only so much kindling.” Malibu and the Palisades, the land of hard living. That’s why so many rich and famous people lived there: because it was so inherently miserable and dangerous.

Mike Davis was full of shit for thirty years — he died in 2022 — and I’ve been rolling my eyes at him throughout. He described Los Angeles as an “apocalypse theme park”, a place of ruin and pain, populated by hardened survivors who, “dutifully struggling”, stagger on through the “Job-like ordeal” of clinging to a brutal landscape.

Also, Sierra Madre has bears. The Los Angeles suburbs are a place of horror and agony, because they back into the mountains, where blood-clawed wild animals prowl and stalk and slaughter. Places where life is especially grim and sanguinary, pgs. 240-41: Bradbury, La Crescenta, Glendora, the areas around the hellscape of Santa Barbara. A poodle was eaten by a mountain lion in Bradbury once, as neighbors gaped in open-jawed terror, YET STILL DO FOOLS ENDURE THE HORROR OF LIVING IN SUCH A PLACE.

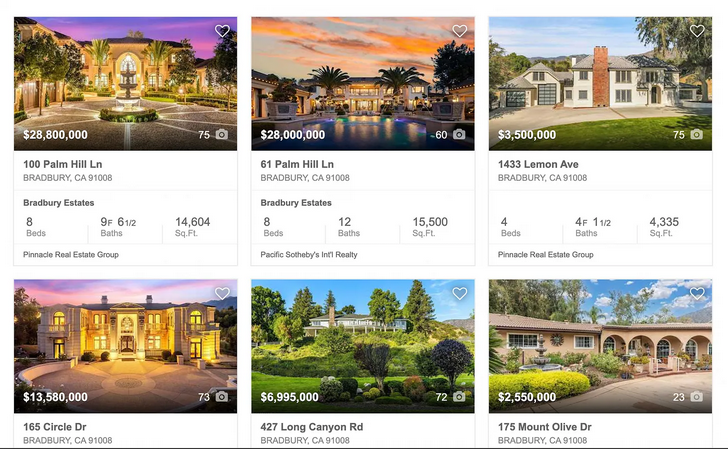

Current real estate listings in Bradbury, a gated hillside community incorporated as an independent city in the San Gabriel Valley with a population of about 900 people:

How then would ye endure such horror, oh pilgrim, to live thus amid such blood and death? How bearest thou brutal existence upon this land?

Famously, in 1999, the Los Angeles Times, which used to be a newspaper, ran a long story examining Mike Davis and his vision of Southern California. It’s full of sentences like this:

- Los Angeles’ most provocative social critic has stretched, bent and broken more than a few facts in “Ecology of Fear,” his latest, darkly themed work on the urban area he claims to love.

- … more than a third of the time there were factual problems with his work.

- Davis concedes the error.

- Davis does not say where he got this piece of information.

- “I honestly don’t know what I’m referring to,” Davis said.

- Some of Davis’ mistakes involve mergers of fact and fiction, including making up a quote.

- Davis attributes the false quote to a mix-up.

- Then he takes readers on a partial flight of fantasy …

- An examination of the Malibu Times article shows that Davis made up the parts about the jewels, the hair color, the kayakers’ occupations, the evidence of their callous classism and the ethnicity of their maids.

- Davis is mischievously unrepentant.

- Davis also merges fact and literary fiction, without acknowledgment, while arguing that Pomona, like other older, outer suburbs, is dying.

And so on.

The Times concluded that Davis could be read as “a polemicist, who makes cogent, incisive arguments on big themes”, but not as “a historian who is expected to be reliable, even on details”.

The Korean War 030 – Revived North Korean Army Strikes Wonju – January 14, 1951

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 14 Jan 2025UN troops around Wonju get a gentle reminder that they’re not only fighting the Chinese. The North Koreans are back, and hammer the weak point in the UN lines all week. With UN forces still organizing a defence, and lots of holes in their formation, will they be able to hold on? Or will failure here undo all of Eighth Army Commander Matt Ridgway’s good work thus far?

Chapters

00:00 Intro

00:45 Recap

01:06 Disposition

02:00 The KPA Attack

05:38 Cracking an Almond

07:55 The New Eighth Army

10:50 At the UN

12:41 Summary

12:57 Conclusion

(more…)