The Tank Museum

Published 30 Sept 2022In this weeks video, David Fletcher discusses the development and features of Striker, another vehicle from the CVRT family.

(more…)

January 26, 2023

Tank Chats #165 | Striker | The Tank Museum

QotD: Non-commissioned officers

“Deltas”, the “socio-sexual hierarchy” spergs inform us, are the good soldiers, the go-along-to-get-along types who know their place in an organization and — crucially — derive their sense of self worth from excelling in it.

Your ideal “delta” is something like a lifer noncom in a non-pozzed military. Back in the days, I’m told, new recruits and civilians used to call crusty old gunny sergeants “sir”, to which the gunny would reply “Don’t call me ‘sir’, I work for a living!” That’s the attitude. Those guys with all the stripes on their sleeves aren’t officers because they lack “command presence”; they’re not officers because they don’t want to be officers. They know themselves, and, crucially, they know where they best fit into the organization’s overall mission. “Get in where you fit in” is, in a very real sense, their identity.

Examples of that kind of guy are tougher to find in the historical literature, which is why we need to develop, and pump up, the archetype. […] the ideal is the centurion, the backbone of Marcus Aurelius’ army. A soldier, a Stoic, a leader … but one who knows, and values, his place in the organization above all things.

Severian, “Be a Centurion!”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-04-07.

January 25, 2023

Sometimes – rarely – the boss really does embody all those “creative genius” tropes

At The Honest Broker, Ted Gioia considers the impact Steve Jobs had on Apple:

I share these reactions, because many other sectors of our culture (especially music) suffer from a similar malaise. And in most instances, the problems start at the top.

I’ve seen in so many different circumstances how the entire organization takes on the personality of the CEO — for better or worse. I’ve also seen how the replacement of a single individual can turn a bad situation into a great one, and vice versa.

The case of Steve Jobs is fascinating, and perhaps alarming too. He left Apple twice, and both times something similar happened.

In the first instance, Jobs was fired as CEO in 1985. The last thing he did before losing his job was launch the Macintosh computer. When he returned to Apple 12 years later, the single biggest source of revenue for the company was still the Macintosh. After more than a decade, the company was depending on the creativity of the guy they fired.

Steve Jobs died in 2011, and we have now reached the exact same time lag as before. Twelve years have elapsed since Jobs’s final departure, and the last big project he undertook before his death was the iPhone. And now after a dozen years, Apple’s largest source of revenues is still the iPhone. Once again, they are riding the momentum of his creativity, and have done shockingly little to expand his legacy.

By the way, in the interim between the two stints as Apple CEO, Jobs founded NeXT and ran Pixar. Fifteen Pixar films now rank among the 50 highest grossing animated films of all time, and they have won 23 Academy Awards. And because of his sale of Pixar to Disney, the entrepreneur’s widow Laurene Powell Jobs inherited 138 million shares of Disney stock.

That’s pretty good results for the lull in your tech career after you’ve been fired.

I know Jobs has many detractors. And maybe he was a hardass boss. In fact, he almost certainly was a hardass boss. But it’s tough to ignore those results — which not only changed a company but the entire culture of our times.

Dinner with Attila the Hun

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 24 Jan 2023

(more…)

QotD: “National unity” and economic commonsense

Protectionists … often trot out various versions of this national-unity argument. The premise is always that when the government uses trade restrictions that reduce the business, wages, and profits of many of us in order to compel the many of us to artificially to increase the business, wages, and profits of some of us, national unity is being served.

But never is a compelling explanation offered of just how the people of the nation are made more united – of just how some common national cause is being pursued – when one subset of the people convinces the government to reduce the real incomes, options, and freedom of another subset of the people.

Economically uninformed economic nationalists … focus only on the gains that protectionism brings to protected domestic producers. … being blind to the losses suffered by all fellow citizens save the relatively small handful of protected interests – or, inexplicably, discounting the reality or severity of these losses – interpret the gains enjoyed by the protected interests as evidence that protectionism is in the national interest.

It’s all (to use an old-fashioned term) poppycock.

Don Boudreaux, “Bonus Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2019-04-01.

January 24, 2023

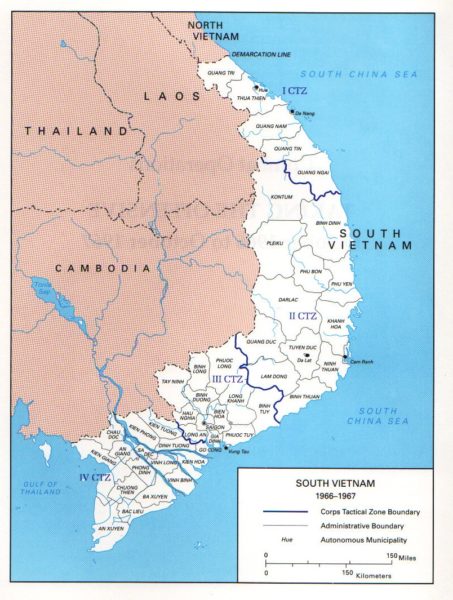

The Vietnam War still has echoes in US politics

In UnHerd, Dominic Sandbrook outlines the end of US involvement in the Vietnam War:

From George L. MacGarrigle, The United States Army in Vietnam: Combat Operations, Taking the Offensive, October 1966-October 1967. Washington DC: Center of Military History, 1998. (Via Wikimedia)

In the course of his troubled presidency, Richard Nixon spoke 14 times to the American people about the war in Vietnam. It was in one of those speeches that he coined the phrase “the silent majority”, while others provoked horror and outrage from those opposed to America’s longest war. But of all these televised addresses, none enjoyed a warmer reaction that the speech Nixon delivered on 23 January 1973, announcing that his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had achieved a breakthrough in the Paris peace talks with the North Vietnamese.

At last, Nixon said, the war was over. At a cost of 58,000 American lives and some $140 billion, not to mention more than two million Vietnamese lives, the curtain was falling. The last US troops would be brought home. South Vietnam had won the right to determine its own future, while the Communist North had pledged to “build a peace of reconciliation”. Despite the high price, Nixon insisted Americans could be proud of “one of the most selfless enterprises in the history of nations”. He had not started the war, but it had dominated his presidency, earning him the undying enmity of those who thought the United States should just get out. But the struggle had been worth it to secure “the right kind of peace, so that those who died and those who suffered would not have died and suffered in vain”. He called it “peace with honour”.

Fifty years on, Nixon’s proclamation of peace with honour has a bitterly ironic ring. As we now know, much of what he said that night was misleading, disingenuous or simply untrue. South Vietnam was in no state to defend itself, and collapsed just two years later. The North Vietnamese had no intention of laying down their weapons, and resumed the offensive within weeks. And Nixon and Kissinger never seriously thought they had secured a lasting peace. They knew the Communists would carry on fighting, and fully intended to intervene with massive aerial power when they did. But then came Watergate. With Nixon crippled, Congress forbade further intervention and slashed funding to the government in Saigon. On 30 April 1975, North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the presidential palace, and it really was all over.

Half a century later, have the scars of Vietnam really healed? It remains not only America’s longest war but one of its most divisive, comparable only with the Civil War in its incendiary cultural and political impact. The fundamental narrative trajectory of the late Sixties — the turn from shiny space-age Technicolor optimism to strident, embittered, anti-technological gloom — would have been incomprehensible without the daily images of suffering and slaughter on the early evening news. It was Vietnam that destroyed trust in government, in institutions, in order and authority. In 1964, before Lyndon Johnson sent in combat troops after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, fully three-quarters of Americans trusted the federal government. By 1976, a year after the fall of Saigon, not even one in four did so.

It was in the crucible of Vietnam, too, that you can spot many of the tensions that now define American politics. Perhaps the most potent example came in May 1970, after Nixon invaded nominally neutral Cambodia to eliminate the North Vietnamese Army’s jungle sanctuaries. First, on 4 May, four students were shot and killed by the National Guard during a demonstration at Kent State University, Ohio. Then, on 8 May, hundreds more students picketed outside the New York Stock Exchange, only to be attacked by several hundred building workers waving American flags.

The “hard hat riot”, as it became known, was the perfect embodiment of patriotic populist outrage at what Nixon’s vice president, leading bribery enthusiast Spiro Agnew, called “the nattering nabobs of negativism … an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterise themselves as intellectuals”. Today it seems almost predictable, just another episode in the long-running culture wars. But at the time it seemed genuinely shocking. And with his brilliantly ruthless eye for a tactical advantage, Nixon saw its potential. When he invited the construction workers’ leaders to the White House two weeks later, he knew exactly what was doing. “The hard hat will stand as a symbol, along with our great flag,” he said, “for freedom and patriotism and our beloved country”.

The Byzantine Empire: Part 9 – The Last Centuries

seangabb

Published 30 Dec 2022In this, the ninth in the series, Sean Gabb gives an overview of the last years of Byzantium, from the Crusader sack in 1204 to the Turkish capture in 1453.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

(more…)

An alternative theory about German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s hesitation to allow Ukraine access to Leopard 2 tanks

I’ve been going on the assumption that the German government was terrified of Russian reaction if they allowed some Leopard 2 tanks to be donated to the Ukrainian forces, but eugyppius points out there’s another strong contending explanation:

Years of peace in Europe, an ageing population and a corresponding focus on expensive social programmes have caused Germany to put its defence industry into near-hibernation. Only a little over 2,000 Leopard 2s have ever seen the light of day. Each one is a hand-built machine that takes two years to make. If Germany permits the export of the European supply of Leopard 2s to Ukraine, the Russians will grind them to nothing within months, and then Europe will have no tanks except the tanks that the Americans sell them:

Defence industry representatives, who wish to remain anonymous, report that the Americans are offering their own used tanks as replacements to [European] countries able to supply Leopard 2s to Ukraine, together with a long-term industrial partnership. Any country that accepts the American offer would be hard to win back for the German tank industry. Berlin’s influence in armament policy would decrease correspondingly.

Tanks are driven by men, who have to be trained in the operation of specific models. Their use moreover requires a whole supply chain of munitions and especially spare parts, which the Americans are eager to offer. The upshot is that, once Europe opts into American armour, it will never switch back, and Germany will be out of the game for good. Nor should we lend much credence to the idea that our very few tanks will make any difference either way for Ukraine’s prospects. The insistence that Scholz release the Leopard 2s is simply an attempt to edge Germany further out of the European arms industry and into a position of lesser political and economic influence in Europe, so that the United States can fill the gap.

Noah Carl, over at the Daily Sceptic, drew attention last week to remarks by the French intellectual Emmanuel Todd that “this war is about Germany“:

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Zbigniew Brzezinski called Eurasia the new “great chessboard” of world politics … The Russian nationalists and ideologues like Alexander Dugin indeed dream of Eurasia. It is on this “chessboard” that America must defend its supremacy – this is Brzezinski’s doctrine. In other words, it must prevent the rapprochement of Russia and China. The financial crisis of 2008 made it clear that with reunification Germany had become the leading power in Europe and thus also a rival of the United States. Until 1989, it had been a political dwarf. Now Berlin let it be known that it was willing to engage with the Russians. The fight against this rapprochement became a priority of American strategy. The United States had always made it clear that they wanted to torpedo [Nord Stream 2]. The expansion of NATO in Eastern Europe was not primarily directed against Russia, but against Germany. Germany, which had entrusted its security to America, became the Americans’ target [in the destruction of the pipeline]. I feel a great deal of sympathy for Germany. It suffers from this trauma of betrayal by its protective friend — who was also a liberator in 1945.

After the anti-Russian sanctions regime and its clear deindustrialising effects on the German economy, followed by the attack on the Baltic Nord Stream pipelines, and even smaller things, such as the high-profile anti-industry protests by the American-funded activist group Letzte Generation, I am willing to believe many conspiratorial things about the Ukraine war.

What Would Browning Do: FN’s New High Power

Forgotten Weapons

Published 30 Sept 2022It seems like everyone is making a copy of the Browning High Power these days, and FN themselves have jumped into the arena as well. What FN is making isn’t just a clone of the original pistol, though — they have built something largely new, taking inspiration and design cues from the original BHP to create a gun more suited to 2022 than 1935.

While the original High Power (or Hi Power, depending on what era you are looking at) is lovingly romanticized by many — and I totally understand why — it has a number of significant shortcomings by today’s standards. It doesn’t feed hollow points well. The triggers are often bad, in part because of the magazine safety. The sights are tiny. The capacity is underwhelming. And most significantly to me, they tend to have bloody hammer bite, forcing you to take a low grip or just suffer through.

The new FN High Power looks to have fixed all of that. It’s a bigger pistol, but it offers a much more comfortable grip, modern style sights, a very nice single action trigger, and 17 round capacity (it does not interchange magazines with the original BHP). Let’s take a closer look at what FN did, and why …

(more…)

QotD: The primary goal of a bureaucracy

In the bureaucratic welfare state, administrative problems grow geometrically with the number of administrators, who devise rules ostensibly to guarantee probity and increase efficiency, but whose effect in practice is to increase the number of administrators necessary to achieve any given end.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Kafka’s Victory”, City Journal, 2005-01.

January 23, 2023

Who was John Wilkes?

Lawrence W. Reed on the life of John Wilkes, a British parliamentarian in the reign of George III:

John Wilkes (1725-1797)

Cropped from a larger painting entitled “John Glynn, John Wilkes and John Horne Tooke” in the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

In the long history of memorably scintillating exchanges between British parliamentarians, one ranks as my personal favorite. Though attribution is sometimes disputed, it seems most likely that the principals were John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, and the member from Middlesex, John Wilkes.

Montagu: Sir, I do not know whether you will die on the gallows or of the pox.

Wilkes: That depends, my lord, on whether I embrace your lordship’s principles or your mistress.

Repartee doesn’t get much better than that. And it certainly fits the style and reputation of Wilkes. Once when a constituent told him he would rather vote for the devil, Wilkes famously responded, “Naturally. And if your friend decides against standing, can I count on your vote?”

Wilkes deserves applause for his rapier wit, but also for something much more important: challenging the arrogance of power. He was known in his day as a “radical” on the matter. Today, we might label him “libertarian” in principles and policy and perhaps even “libertine” in personal habits (he was a notorious womanizer). His pugnacious quarrels with a King and a Prime Minister are my focus in this essay.

Born in London in 1725, Wilkes in his adult life was cursed with bad looks. Widely known as “the ugliest man in England”, he countered his unattractive countenance with eloquence, humor, and an eagerness to assault the powers-that-be with truth as he saw it. Fortunately, the voters in Middlesex appreciated his boldness more than his appearance. He charmed his way into election to the House of Commons as a devotee of William Pitt the Elder and, like Pitt, became a vociferous opponent of King George III’s war against the American colonies.

Pitt’s successor as PM in 1762, Lord Bute of Scotland, earned the wrath of Wilkes for the whole of his brief premiership. Bute negotiated the treaty that ended the Seven Years War (known in America as the French & Indian War), which Wilkes thought gave too many concessions to the French. Wilkes also opposed Bute’s plan to tax the Americans to pay for the war.

[…]

George III took it personally. He ordered the arrest of Wilkes and dozens of his followers on charges of seditious libel. For most of the nearly thousand years of British monarchy, kings would have remanded foes like Wilkes to the gallows forthwith. But as a measure of the steady progress of British liberty (from Magna Carta in 1215 through the English Bill of Rights in 1689), the case went to the courts.

Wilkes argued that as a member of Parliament, he was exempt from libel charges against the monarch. The Lord Chief Justice agreed. Wilkes was released and took his seat again in the House of Commons. He resumed his attacks on the government, Bute’s successor George Grenville in particular.

Monte Cassino, the Battle Begins – Ep 230 – January 21, 1944

World War Two

Published 21 Jan 2023The Allies have reached the linchpin of the German defenses in Italy, but a first attack proves disastrous. It does, though, divert troops from where they soon plan to make landings behind enemy lines. Meanwhile in the USSR, the huge Soviet offensive in the north makes great gains against the stunned Axis forces.

(more…)

Jeremy Clarkson and “the swamp of arrogant prejudice and self-gratification which sits at the bottom of the brain”

Nicholas Harris recounts the story of Jeremy Clarkson’s steady rise and sudden recent fall after a crude reference to someone or other in a newspaper article:

“Ask Clarkson. Clarkson knows — people like fast cars, they like females with big boobies, and they don’t want the Euro, and that’s all there is to it.” This surmise, from Peep Show, captures the essence of Jeremy Clarkson’s Noughties appeal — approvingly for those who liked him, and scandalously for those who didn’t. The spawn and spokesman of the English male id. Insular, impudent and straightforward in taste. And if that weren’t enough, he was also into cigs, engines and the Second World War.

For the minority of a more severe, moralistic, and joyless disposition, this made him a national-psychological defect to be suppressed, or ideally exposed and exorcised. Before Piers Morgan, Nigel Farage or Donald Trump provided such stern competition, it was a small badge of honour on the Left to publicly hate Clarkson. But for many of us (probably a majority at his peak) he was a vulgar treat to indulge. For the length of a Sunday column or an episode of Top Gear, we could wallow harmlessly in the swamp of arrogant prejudice and self-gratification which sits at the bottom of the brain. At a time of minimal collective loyalty, the nation could reliably divide into those two tribes. Clarkson the monster, or Clarkson the geezer. Wokery vs blokery. A version of the same split is fuelling the current Clarkson row, but with the weight of opinion reversed.

[…]

But his spiritual and popular appointment to the English is a far tougher thing to dismiss. He is, like it or not, quite a lot of us writ ludicrously, satirically large. Like a 21st-century John Bull: to paraphrase Auden, a self-confident, swaggering bully of meaty neck and clumsy jest. Whatever Clarkson’s professional fate, the question of whether our society can tolerate him has implications for the stomach and sensibility of the national character, of which he is a significant avatar and champion. And his rise and fall reads as a history of a changing English firmament, one in which public morality has come to supersede mere entertainment.

Plenty of time and work went into the germination of such a figure. Clarkson’s early life is a whistle-stop tour of the English class system. He was born rural, lower-middle class, Yorkshire. But, in a wonderful twist of fate, the Clarkson family came into money after his parents won the exclusive rights to sell Paddington Bear dolls, based on the ones they had made for him and his sister. With aspirational intent, Clarkson was sent to Repton, one of the North’s oldest private schools. There, he smoked, pranked and failed his way to expulsion, developing the likeable loutishness which is his career mainstay. And then he jumped social tracks again, entering the lowest rungs of the Fourth Estate at the Rotherham Advertiser.

A public schoolboy who can still boast that he crashed out of education with a C and two Us at A Level. The ingredients were in place for a broad, classless appeal. But Clarkson really came of professional age in the new meritocracy of Thatcher and Murdoch, a place where common touch came to supersede common background (something also exploited by Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage). It was an England of quick, coarse wit, and quicker, coarser money; of the triumphant red-top, and the unrepentant “lad”. It suited Clarkson perfectly. Flush with entrepreneurial spirit, in Eighties London he had the wheeze of syndicating car news and reviews from his own company to the regional press. It was a money-maker which introduced him to motoring journalism and eventually to the producers of Top Gear.