Geography Now

Published 23 Nov 2016Seriously though. Do those squats bro.

(more…)

June 16, 2023

Geography Now! Finland

QotD: Sailing ships in the real world versus sailing ships in Rings of Power

There are a bazillion ways to rig a ship (a lot of them with really fun names), but all sails function in one of two basic ways. First it’s worth noting every ship operates in both a “true wind” (the direction the wind is actually blowing) and an apparent wind, which is the combination of the true wind with the direction the ship is sailing and its speed; the apparent wind is what matters for sail dynamics because that’s the wind that the sails experience. If a ship is sailing at 8 knots and the wind is moving at 12 knots, but the ship and the wind are moving in the same direction, the apparent wind the ship experiences is just 4 knots. On the other hand, if the wind speeds remain the same but we have the same ship moving perpendicular to the wind, the apparent wind is going to actually be 14.4 knots and come from a direction between the ship’s heading and the wind’s source.

Square sails, which are rigged perpendicular to the direction of the ship work by having the wind strike the sail and pile up into it, which creates a high pressure zone behind the sail (because all of the air, blocked by the sail, is “stacking up” there) and a low pressure zone in front of the sail, which pushes the ship forward, technically a function of aerodynamic drag. The upside is that square sails can produce a lot of power, which is handy for big, heavy ships, especially in areas with predictable and favorable winds (such as the Atlantic trade winds). The downsides are two: on the one hand, top speed is limited because the faster the ship goes, the lower the apparent wind on the sails, which in turn reduces how much they can push the ship. On the other hand, square sails only work if the ship is moving in more-or-less the same direction as the wind is, within about 60 degrees or so (so the ship has a c. 120 degree range of movement relative to the wind). Moreover, for square sails to work, the air hitting them from behind needs to be substantially confined by their shape; this is why square sails are made to billow outward into an arcing shape as the wind hits them, instead of being held taught and fully flat against the mast.

Triangular or lateen or fore-and-aft sails work on a different principle. They are arranged parallel to the direction of the ship (that is, fore-and-aft of the mast, thus the term) and want to also be close to parallel to the wind (both square and triangular sails can, in some configurations, be moved around the mast to a degree to get an ideal direction to the wind). The way they work is that the wind hits the sail on its edge and the air current splits around the sail, but not evenly; the sail is turned so that the back side takes more wind, causing the sail to billow out, creating a wing-like shape when viewed from above. That in turn acts exactly like a wing, creating a high pressure zone behind the sail and a low pressure zone in front of the sail and thus generating aerodynamic lift as the wind passes over the surface (rather than pressing up behind it) the same way that an airplane’s wings keep it in the air. The clever part about this is that the lift generated doesn’t have to be in the same direction the wind is going, so a ship using these kinds of sails can move up to within around 45 degree of the wind (sailing “close hauled” – a ship rigged like this thus has a much larger 270 degree range of motion relative to the wind). Also – as noted above – depending on the ship’s “point of sail” (direction of movement relative to the wind), accelerating may not decrease the wind’s apparent speed (because you may not be sailing directly away from it), and so triangular sails often function better in light winds, sailing into the wind, and at very high speeds (but they provide less power for large, heavy ships sailing with the wind). And again, there is a lot of complexity in terms of the different functions of these types of sails, but we’re really just trying to make a fairly simple point here so everyone please forgive the simplification.

And that’s it: all sails work on one of those two principles (at any given time); the point in discussing this is to note that we’re dealing not with aesthetics here but with objects that need to interact in fairly fundamental ways with aerodynamics and so have shapes that are dictated by that function (and also, sails are cool). You can combine those two principles in a lot of exciting ways to create different “rigs” with different sailing qualities, but you those principles are your options – you cannot create some other kind of sail which works on different principles. Indeed, most of the more complex sailplans of larger ships use a combination of square and lateen sails, but each sail in the plan must be using one of these two principles; there are no other options.

And those of you looking back at what these ships [in Rings of Power] look like may have already guessed the problem here. These are clearly square-rigged ships; the sails are all perpendicular to the ship’s direction and the sail shape is symmetrical over the keel (that is, same shape on the port and starboard) and are unable to be angled in any event. But every single sail has a gigantic hole in the center because of the split mast. So the air you want to build up behind the sail is instead flowing through the hole between the masts. The sails even angle slightly, curling backwards at their outer edges channeling the air towards the gaps. But that air flowing through the gaps is going to lessen (not remove, but substantially lesson) the pressure differential over the sail which will cut the drag the sails generate which will make the ship much slower.

What is worse is that between the two masts and between the foremast and the bowsprit, the ships mount additional secondary sails. Now in a rig-plan that made any sense, these would be triangular sails in both shape and principle (e.g. gaff-rigged sails incorporated into a square-rig sailing pattern common for full rigged ships as well as staysails between the masts or between the foremast and the bowsprit, also common for full rigged ships), but the designers here have only managed one of those two things. The sails are triangular in shape, but are positioned perpendicular to the wind direction and then symmetrically matched. That means they both do nothing with the wind moving through that center channel we’ve created, but also their triangular shape is entirely useless because they’re functioning on drag instead of lift.

It’s not that this sail plan wouldn’t work: the big sails would create at least some aerodynamic drag which would push the ship forward. But this is a sail plan which would work much more poorly than a far more basic plan with just a single central mast mounting a single very large square sail. You could even keep the exotic junk-style sail supports (they’re called battens; everything on sailing ships has a funny name) if you wanted and just make the ships junk-rigged! Or, if you want a lot of fancy sails which aren’t in square shapes, you could go with a multi-masted dhow or xebec sail plan which would give you lots of overlapping triangular sails and also fit the Mediterranean/Roman vibe you were going for.

Moreover, while these sails aren’t square shaped, this is a pure “square sail” ship rig, which for ocean-going ships ostensibly used by great mariners is awful. Square sails only work well when running before the wind: they “tack” (zig-zagging from one close-hauled point of sail to another to climb up the wind) really poorly; some pure square-rigged ships cannot tack at all without the assistance of rowers. That’s is part of the reason why “full rigged” square-sailed age of sail ships nevertheless had triangular sails in gaff-rigging or as stay-sails or what have you, to enable the ship to tack effectively (the fancy term for this is how “weatherly” a ship is: how able it is to sail close to the wind; weatherlyness also depends on hull shape and a host of other factors). With a pure square-sail setup, these ships can only go in the direction of the wind, which is going to make it impossible to use them effectively as ocean-going ships because the prevailing winds on the ocean are very consistent: they will almost always be blowing the same way, which means these ships can sail out, but then can’t sail back. In short these ocean-going mariners have ships which cannot go on the oceans.

And of course this has been a theme of these posts but please, showrunners: when you are doing the visual design for a fantasy-historical society, you are not going to outsmart centuries of professional shipwrights with a brainstorming meeting and some concept art. So instead of trying to show that the Númenóreans are great mariners (“the sea is always right!”), which is the point of giving their super-cool ships so much screentime and is an essential thing to establish about their society, by making up a ship design that is going to end up invariably being much worse than historical designs, just go adopt a historical design that was successful. For my part, I’d have probably contrasted traditional Elven ships with a single sail-type (probably square) on a single mast with the advanced Númenóreans using lots of lateen sails.

That said, the fact that the Númenórean ships are terrible is fine because frankly, I wouldn’t want to sail to this battle either.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Nitpicks of Power, Part III: That Númenórean Charge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-02-03.

June 15, 2023

Thursday tab-clearing

A few items that I didn’t feel required a full post of their own, but might be of interest:

- Justin Trudeau’s government is clearly interested in moving to a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), but “Canadians are not at peace with the idea of cash vanishing into thin air, with a consistent 80 per cent of respondents having no plans to go cashless“

- There’s an ongoing shortage of Adderall in the United States … and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) is behind it.

- Alasdair Beckett-King explains what’s wrong with every time travel movie – https://youtu.be/zI0aBzA2K9s

- The man who visited Lenin’s Soviet Union and said “I have been over into the future, and it works.”

- Kim du Toit isn’t a believer in the official inflation statistics: “When the history of this era comes to be written, one of the most egregious falsehoods to be exposed will be the ‘official’ inflation rate.”

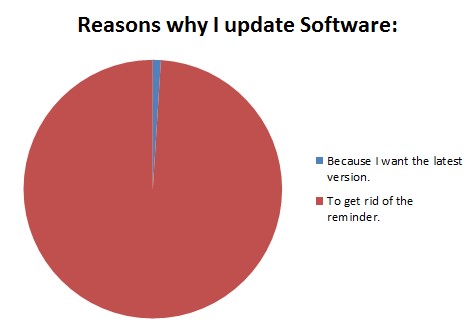

- Random meme of the day:

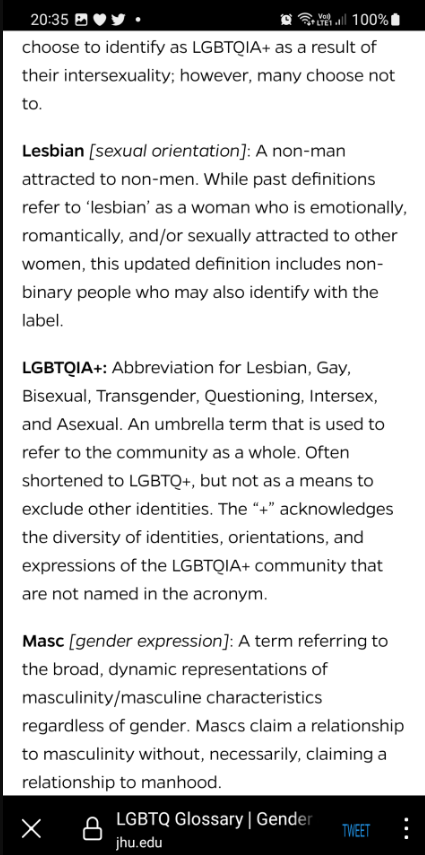

Sarah Hoyt objects to being an “imaginary creature”

Recent revisions to the quasi-official dictionary of the woke English language seem to have classified individuals like Sarah as “non-men”:

I was born female in a country that was profoundly patriarchal and, back then, patriarchal without guilt. So, it was acceptable to make jokes about women being dumber than men. And it was acceptable for teachers to assume you were dumb because female.

Most of these things amused me. It was always fun in mixed classes after the first test to watch the teacher look at my test and at the boys in the class trying to figure out what parent was so cruel as to name their son a girl’s name.

I enjoyed breaking people’s minds. And once I was known in a group or place, I was not treated as inferior. The only things that truly annoyed me were the ones I thought were arbitrary restrictions, like not going out after 8 pm alone. Took flaunting them a few times to find out they weren’t arbitrary. Or rather, they were arbitrary but since culture-wide flaunting was dangerous, and I was lucky not to pay for the flaunting with life or limb.

Yes, I went through a phase of screaming that I was just as good as any man. Then realized it was true and stopped screaming it.

Then got married and had kids, and realized I was just as good but different. I could do things men couldn’t do. Parenthood is different as a woman. And none of it mattered to my worth, just like being short and having brown hair doesn’t make me inferior to tall blonds. Just different.

And even though I’m a highly atypical woman, at the beginning of my sixth decade, I find myself completely at peace with the fact I am a woman and not apologetic at all for it.

Imagine my surprise when I found out women don’t exist. There’s only man and non-man.

This nonsense, from here, has got to stop. When you get so “inclusive” you’re excluding an entire biological sex (but curiously not the other) you might want to re-evaluate your principles. Also, your sanity.

Yes, I know, saying this makes me a TERF, which is nonsense. Maybe a TERNF, since I’ve not called myself a feminist since I was 18 and realized feminism aimed for making women “win” at men’s expense. It wasn’t aiming for equality but for “equity” and since I never needed a movement to outcompete males, I decided it was spinach and to h*ll with it.

Also I’m not trans-exclusionary. If women don’t exist, what the heck are men who are trans trans TO? Non-man? Uh … what? What are drag queens imitating? Is it just non-man?

See Inside King Tiger | Tank Chats Reloaded

The Tank Museum

Published 10 Mar 2023In this video, Chris Copson gives us a glimpse inside one of the most formidable German tanks of World War II – the King Tiger.

(more…)

June 14, 2023

Wednesday web-droppings

A few items that I didn’t feel required a full post of their own, but might be of interest:

- “Teacher, leave them kids alone!” – Middle schoolers staged a revolt on the day they were told to wear rainbow colors to celebrate pride. They wore red, white, and blue, and said their pronouns were “U.S.A.” Woke faculty is freaking out.

- Sir Humphrey answers the question “Is the Royal Navy still a truly ‘blue water navy’?“

- Brendan O’Neill is nostalgic for a long-distant past before everyone started sounding like off-brand Unabomber disciples.

- Tim Harford on “Giffen goods“

- Random meme of the day:

The sinking of Norwegian frigate HNoMS Helge Ingstad in 2018

CDR Salamander must follow Norwegian court cases more closely than I do … which is “not at all” in my case. Oddly, I was just thinking about the loss of HNoMS Helge Ingstad last week, and here’s follow-up information from the appeals process:

HNoMS Helge Ingstad, a Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate commissioned in 2009.

Photo detail via Wikimedia Commons.

The court case against the officer of the watch (vaktleder) and its appeals has brought the issue back to the front in Norway.

In yesterday’s Forsvarets Forums article (remember to translate it), retired Norwegian naval officer with multiple command tours, Hans Petter Midttun, outlines a must read wire brushing of the entire “optimal manning” concept.

You will see that his view of what it caused to the Norwegian Navy’s nightmare is a direct parallel of that happened to the US Navy in that horrible month of 2017; too much to do with too little people with too thin training.

Let’s dive in;

The Ministry of Defense (FD), the Defense Staff (FST) and the Norwegian Navy (SST) have, in my opinion, knowingly or unknowingly breached the prerequisites for proper operation of the frigates.

My claim is rooted in 23 years of frigate competence. I have held most of the operational positions in the frigate force. This includes the positions as ship commander at KNM Narvik and KNM Roald Amundsen, as well as a period at the Navy’s competence center and two periods as staff officer for the “shipowner”.

That is the extended way of saying, “I know you because I am you“. He’s raising his voice here because it is personal and he wants to go on the record that there are causes to this mishap much deeper than just the one officer on trial.

In light of the extensive changes that lay before the Armed Forces in 2004, we considered it crucial to describe the assumptions on which the staffing concept was based. It was not a new concept. It just hadn’t been described before. It had been developed as a consequence of continuous efficiency measures in the 90s.

One of our main messages was:

The Lean Manning Concept was not chosen because it was operationally smart. It was chosen because it enabled the Navy to man and sail (at the time) a balanced structure. It was an absolute minimum crew that could only work if all the prerequisites were met.

The last part — here on the Front Porch we describe that as “exquisite“. Everything — and everyone — has to work just right to make the formula work.

It doesn’t work that way outside the briefing room. Never does.

During a five-year period, the crew sailed one year less than what Nato considered necessary to maintain the operational level (for a frigate with a larger crew). But in addition, the crews never reached more than a maximum of 80 percent of their expected combat power. This meant that each year the training activity started at a lower level than the previous year.

You design minimum manning — and you get 80% of the minimum. It might work for awhile in peace — but it unquestionably won’t work in combat. Exactly the stew that contributed to the McCain & Fitzgerald collisions. Senior leaders try to convince everyone that 9-to-11 month deployments are a “new normal” and humans can do 100-hr work weeks for weeks to months on end with no downside. Just sadistic malpractice.

Michael Wittmann: The Fascination with the Panzer Ace of Villers-Bocage

OTD Military History

Published 13 Jun 2023American historian, Carlo D’Este seemed to have an intense admiration for Michael Wittmann, the SS Panzer ace best known for his actions at Villers-Bocage in Normandy on June 13 1944. This video shows why this problematic and even misplaced.

(more…)

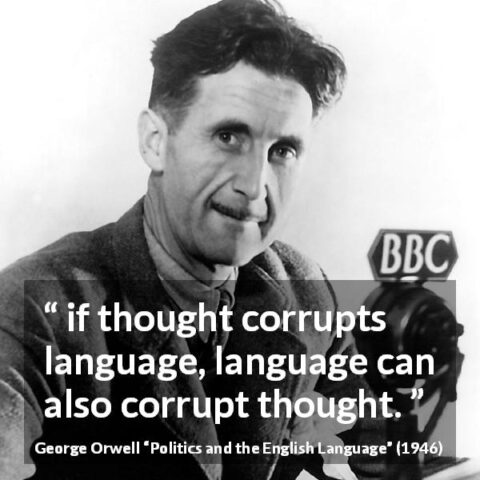

“‘Misogyny’ is overtaking ‘fascist’ in the ‘I Don’t Own a Dictionary’ championships”

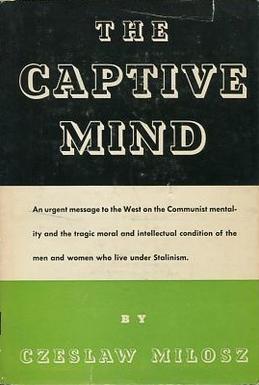

Christopher Gage suspects that George Orwell lived in vain:

In his essay, “Politics and the English Language”, George Orwell lamented the decline in the standards of his mother tongue.

For Orwell, all around him lay the evidence of decay. Orwell argued sloppy language came from and led to sloppy thinking:

A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language […] It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

With his effortless knack for saying in plain English the resonant and enduring, Orwell’s dictum is obvious as soon as uttered.

Orwell wrote that back in 1946. What would the author of Animal Farm and 1984 make of today’s standards?

“Misogyny” is overtaking “fascist” in the “I Don’t Own a Dictionary” championships.

Spend five minutes online, and you’ll encounter words defined in their starkest definitions. Words like “misogyny”, “misandry”, and “narcissist”, once possessed specific meanings. Now they mean whatever the speaker claims they mean.

The beauty of the English language lies in its precision. Sadly, those who populate the land which spawned the English language wield the language with all the grace and precision of a meat hook.

According to The Guardian, the recent Finnish election was suppurated with misogyny and fascism.

In that election, the one debased in misogyny and fascism, the losing incumbent Sanna Marin, a woman, won more seats in parliament than in 2019. The three candidates with the most votes — Riikka Purra, Sanna Marin and Elina Valtonen — were all women. Women lead seven of the nine parties returned to parliament — including the “far-right” Finns Party.

The Guardian didn’t permit reality to spoil a good headline.

As Orwell had it, “Fascism” is a hollow word. In the essay mentioned above, he said: “The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’.” In modern parlance, the same applies to “misogyny”. “misandry”, “narcissism”, “gaslighting”, and just about every other buzzword shoehorned into a HuffPost headline.

Battle Of The Rivers (1944)

British Pathé

Published 13 Apr 2014Title reads: “Battle of the Rivers”.

Allied Forces invasion of France.

Various shots of mechanised units of the British and Canadian army preparing for assault on the Rivers Odon and Orne. Infantry mount the Sherman tanks and they head along the dusty road. Various shots of Sherman flail tanks passing camera (not flailing). Road bank collapses and one tank rolls onto its side

Various shots of Lancaster bombers over industrial area of Vaucelles. Aerial shots of bombs dropping from planes. Night shot of coloured markers cascading down to light up target area. More aerial shots, including L/S of Lancaster bomber crashing in flames.

Various shots of heavy artillery in action in the fields. Various shots of Royal Engineers putting Bailey Bridge across the Caen Canal. L/S of tanks crossing the bridge. Various shots of badly damaged industrial area near Caen. L/S of Canadian tanks on the move over open countryside and tracks. We see a soldier extinguishing flames where a tank’s grass camouflage has caught fire. The tanks cross a railway line.

Various shots of Winston Churchill being greeted by American officers as he arrives by plane in the Cherbourg area. He then tours the peninsula, looking at structures that were supposed to be V2 sites. M/S of Churchill climbing into spotter plane (“flying jeep”), piloted by Air Vice Marshal Broadhurst. Various shots of Churchill driving around Caen in an open-topped car, with him are Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery (Monty) and General Dempsey. Various shots of Churchill posing with a group of soldiers, he then spends some time chatting to them.

(more…)

QotD: In hindsight, calling it “Operation HONOUR” was quite ironic

I spent my subaltern years in the light of Operation HONOUR, the signature project of then-Chief of Defence Staff General Jonathan Vance. Operation HONOUR was a massive culture change effort intended to address the findings of the Deschamps Report, which had exposed the “underlying sexualized culture in the CAF that is hostile to women and LGTBQ members, and conducive to more serious incidents of sexual harassment and assault”. General Vance went to great lengths to emphasize that Operation HONOUR was, in fact, a military operation and not a mere policy. Slicing out the tumour of sexualized culture was our mission and the General’s words were our orders. During my first ever round of quarterly performance evaluations, I reported to the company commander that one of my NCOs was non-compliant with the principles of Operation HONOUR.

Loyalty up, remember?

As a young soldier, I had actually worked for this particular NCO. He was an artifact of the Old Army and had a reputation as a hardman. He liked to brag about picking Friday night fights in Native bars out on the Prairies (he wore weighted gloves for extra knock-out power). He described to us in detail what he would do to his wife after a training weekend. He told us she would never say no, followed up with a chuckle and “like she has a choice”. If you were weak in his eyes, he’d belittle you publicly as a “queer” or a “faggot”. The funny thing was that this guy was overweight and never showed up for ruck marches or PT tests. His annual conduct-after-capture briefing was basically forty minutes of “you’re gonna get raped but that doesn’t make you gay”. One of his favourite war stories was about stray dog duty in Bosnia. He’d lure in the strays with peanut butter on the end of shotgun then blow their brains out. Riveting stuff.

Overnight I had gone from from being this man’s subordinate to being his superior, so when the General said we had a duty to report, I did my duty. The next week I was in front of the Regimental Sergeant-Major being asked why I was interfering with a strong NCO’s career prospects. That’s when I learned that loyalty up meant loyalty to the Regiment, and that sensitive matters such as this were handled internally and off the record. That one-way conversation was a major push towards putting in my application for the Regular Force. I didn’t want to be around that type of nonsense (“oh my sweet summer child” says the peanut gallery). Not long after I left, my former supervisor sexually assaulted the mess steward.

[…]

In February 2021, an investigation was opened into General Jonathan Vance, who had just finished his tenure as Chief of Defence Staff. Major Kellie Brennan, a subordinate of Vance at various times, accused him of a preventing her from disclosing their long-running affair. Since their relationship began in 2001, Vance had been married twice. DNA testing confirmed that Vance was the father of one of Brennan’s children, but he had never acknowledged or taken responsibility for the child. Vance plead guilty to obstruction of justice in March 2022 and received a conditional discharge with twelve months of probation.

The heat and light generated by an investigation of the outgoing Chief of Defence Staff led to an unprecedente level of scrutiny on the CAF’s senior leadership. In 2021 alone, the Governor General of Canada, the Minister of National Defence, the incoming Chief of Defence Staff, the Vice Chief of Defence Staff, Commander Canadian Special Operations Command, and Commander Military Personnel Command, amongst others, would resign, retire, or be re-assigned amidst allegations of impropriety. Since 2021, recruiting and retention levels have continued to free fall and the federal government has set aside $900 million in class-action lawsuit compensation for current and former CAF members who experienced sexual harassment, assualt, or discrimination. The social trap has been sprung.

“Shady Maples”, “A Question of Loyalty”, The Powder Horn, 2023-03-12.

June 13, 2023

Liberal woman frustrated she can’t find non-conservative but traditionally masculine men

Tom Knighton responds to a progressive woman’s lament:

She is at a loss because she wants to be with a masculine man but doesn’t want to compromise her morals and values. She asks her followers if she is asking for too much when she requests a man she can be “equal” with while he still provides for her.

What she doesn’t seem to get is that it was women like her that basically destroyed manhood to the point that there’s little chance she’ll find a liberal guy with traditional values.

See, liberal men are basically obligated to take the subservient role. They’re required by their ideology to accept that the woman is just as capable — and obligated — to be at least an equal in providing for the family, if not the provider herself.

Failure to act according to this, at least in their minds, is to undermine the feminist values the left claims to hold so dear.

It didn’t have to be this way. It was always possible to empower women without trying to tear masculinity down, which is what has been happening.

Opening doors for women, for example, is one of those things guys used to do all the time. It wasn’t that women were somehow incapable of operating a doorknob. It was because it was just something a gentleman did.

Now, if a man opens the door for a woman, he’s taking a chance. Will she appreciate it or will she launch into a feminist diatribe about the patriarchy?

Leftist men already know which they expect, so they do no such thing. Guys with more of a traditional lean, however, can and will open that door because they’re not impressed with feminist screeching.