Robert DuHamel

Published 13 Aug 2019You’ve heard about it. You’ve read about it. You’ve watched the television documentaries. The de Havilland Comet. Two mysterious crashes in the Mediterranean near Rome. 56 people dead. The planes exploded in mid-air when their pressure cabins ruptured at the corners of the square windows. A hard lesson learned about pressurized airliners, square windows, and metal fatigue. But you haven’t heard the whole story. Find out what really happened in this first video in the series Aircrash Minority Report.

Thumbnail: a Convair XF2Y-1 Sea Dart breaking up after exceeding the stress limit of the airframe. The crashes of the de Havilland Comets would look similar.

References:

FAA Lessons Learned: de Havilland DH-106 Comet: https://lessonslearned.faa.gov/ll_mai…

Failure-Analysis-Case-Studies-II – David R. H. Jones: https://vietnamwcm.files.wordpress.co…

June 26, 2021

It Wasn’t the Square Windows – The de Havilland Comet Crashes – Aircrash Minority Report

June 25, 2021

QotD: Moore’s Law

Moore’s Law is a violation of Murphy’s Law. Everything gets better and better.

Gordon Moore, quoted in “Happy Birthday: Moore’s Law at 40”, The Economist, 2005-03-26

June 23, 2021

June 18, 2021

Feeding “the masses”

Sarah Hoyt looked at the perennial question “Dude, where’s my (flying) car?” and the even more relevant to most women “Where’s my automated house?”:

The cry of my generation, for years now, has been: “Dude, where’s my flying car?”

My friend Jeff Greason is fond of explaining that as an engineering problem, a flying car is no issue at all. It is as a legal problem that flying cars get interesting, because of course the FAA won’t let such a thing exist without clutching it madly and distorting it with its hands made of bureaucracy and crazy. (Okay, he doesn’t put it that way, but I do.)

[…]

But in all this, I have to say: Dude, where’s my automated house?

It was fifteen years ago or so, while out at lunch with an older writer friend, that she said “We always thought that when it came to this time, there would be communal lunch rooms and cafeterias that would do all the cooking so women would be free to work.”

I didn’t say anything. I knew our politics weren’t congruent, but really the only societies that managed that “Cafeterias, where everyone eats” were the most totalitarian ones, and that food was nothing you wanted to eat. If there was food. Because the only way to feed everyone industrial style is to take away their right to choose how to feed themselves and what to eat. And that, over an entire nation, would be a nightmare. Consider the eighties, when the funny critters decided that we should all live on a Russian Peasant diet of carbs, carbs and more carbs. Potatoes were healthy and good for you, and you should live on them.

It will surprise you to know – not — that just as with the mask idiocy, no study of any kind supports feeding the population on mostly vegetables, much less starches. What those whole “recommendations” were based on was “diet for a small planet” and the bureaucrats invincible ignorance, stupidity and assumption of their own intelligence and superiority. I.e. most of what they knew — that population was exploding, that people would soon be starving, that growing vegetables is less taxing on the environment and produces more calories than growing animals to eat — just wasn’t so. But they “knew” and by gum were going to force everyone to follow “the plan”. (BTW one of the ways you know that Q-Anon is in fact a black ops operation from the other side; no one on the right in this country trusts a plan, much less one that can’t be shared or discussed.) Then the complete idiots were shocked, surprised, nay, astonished when their proposed diet led to an “epidemic of obesity” and diabetes. Even though anyone who suffered through the peasant diet in communist countries, could have told the that’s where it would lead, and to both obesity and Mal-nutrition at once.

So, yeah, communal cafeterias are not a solution to anything.

My concern about the “automated house of the future” is nicely prefigured by the “wonders” of Big Tech surveillance devices we’ve voluntarily imported into our homes for the convenience, while awarding untold volumes of free data for the tech firms to market. Plus, the mindset that “you must be online at all times” that many/most of these devices require means you’re out of luck if your internet connection is a bit wobbly (looking at you, Rogers).

June 17, 2021

Encouraging innovation by … rejigging the honours system

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers how one man’s efforts to encourage and reward innovation in the United Kingdom eventually led to “mere inventors” receiving honours that once were dedicated to military paladins and political giants:

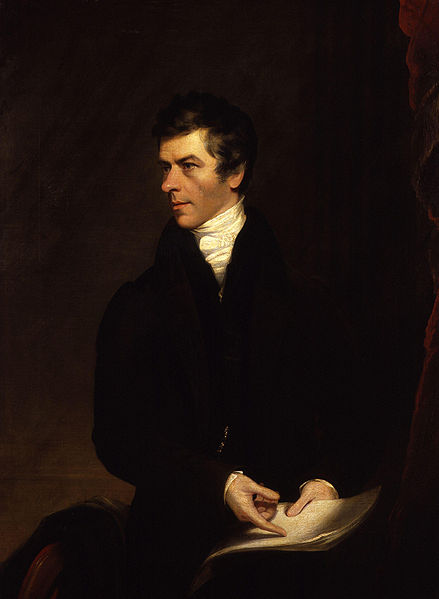

Henry Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux, by James Lonsdale (died 1839), given to the National Portrait Gallery, London in 1873.

Image from the National Portrait Gallery via Wikimedia Commons.

One of my all-time favourite innovation evangelists is the nineteenth-century barrister, journalist, and politician Henry Brougham. He was an innovator himself, in the late 1830s designing a form of horse-drawn carriage, and as a teenager even managed to get his experiments on light published in the Royal Society’s prestigious Transactions. But his main achievements were as an organiser. Clever, dashing, and articulate, the son of minor gentry, he was an evangelist extraordinaire. In the 1820s he helped George Birkbeck to found the London Mechanics’ Institute (which survives today as Birkbeck, University of London), was instrumental in the creation of University College London (to provide a university in England where you didn’t have to swear an oath to the Church of England), and founded the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (to print reference works and textbooks cheaply and in bulk). They were all organisations intended to widen access to education, spreading science to the masses.

He also presided at the opening of many more worker-run mechanics’ institutions, libraries, and scientific societies. As a Member of Parliament who went out of his way to support workers’ efforts at self-education, even though none of them could vote, Brougham thus became something of a celebrity to working-class inventors. John Condie, born in Gorbals, Glasgow, to poor parents, and apprenticed to a cabinet maker, would become a prolific and successful improver of iron-making, locomotive springs, and photography, as well as an inspiring lecturer on scientific subjects in his own right — his students at the Eaglesham Mechanics’ Institution were reportedly so engrossed that they would attend his evening classes until midnight. Having once exhibited a model steam engine at the opening of the Carlisle Mechanics’ Institution, however, Condie was reportedly “not a little proud” that Brougham — who had presided at the opening — recalled the model over thirty years later. The detail comes from Condie’s obituary notice in the local papers; I like to think that it was a story upon which he frequently dined out.

Brougham’s celebrity, I suspect, made him appreciate the usefulness of status and prestige, and his influence only grew when in 1830 he was made a lord and appointed Lord High Chancellor — a high-ranking ministerial position, which he held for four years. Brougham was soon behind many efforts to increase the visibility of inventive role-models. The nineteenth-century mania for putting up statues — to people like Johannes Gutenberg, Isaac Newton, and James Watt — often had Brougham or his political allies behind them. Brougham even hoped that while the “temples of the pagans had been adorned by statues of warriors, who had dealt desolation … ours shall be graced with the statues of those who have contributed to the triumph of humanity and science”.

His hero-making extended to print, too, when in the 1840s his Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge embarked on publishing a comprehensive biographical dictionary — an early forerunner to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, but with the extraordinary aim of covering notable individuals from all over the world. It managed to print seven volumes covering the letter “A” before financial considerations forced the whole society to cease, but in 1845 Brougham published Lives of Men of Letters and Science who Flourished in the Time of George III, in which he showcased a handful of eighteenth-century literati and scientists from whom readers were to draw inspiration.

And Brougham tried to raise the status of inventors who were still living. This was done by co-opting a Hanoverian order of chivalry, the Royal Guelphic Order (by this stage the kings of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland were also simultaneously the kings of Hanover). The order was generally used to recognise soldiers, but an interesting precedent had been set when the astronomer Frederick William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus, had been made a knight of the order in 1816. So when Brougham rose to power in the 1830s, he envisaged using it more widely, to recognise inventors, scientists, and medical pioneers, as well as literary scholars like museum curators, archivists, antiquarians, historians, heralds, and linguists. Thanks to Brougham’s machinations, the knighthood of the order was offered to the mathematician James Ivory, the scientist and inventor David Brewster, and the neurologist Charles Bell (after whom Bell’s Palsy is named). It was later also awarded to serial inventors like John Robison, who improved the accuracy of metal screws, experimented with cast iron canal locks and the water resistance of boats, and applied pneumatic presses to cheesemaking.

One problem, however, was that the Royal Guelphic Order was considered second-rate. It was technically a foreign order, and did not actually entitle one to be called “Sir” in the UK. The mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage was apparently insulted to have been fobbed off with the offer of a Guelphic knighthood instead of a British one. Although William Herschel had accidentally been called “Sir” during his lifetime, this was soon realised to be a mistake in protocol. When his son John — a scientific pioneer in his own right — was also made a knight of the order, he was also quietly knighted normally a few days later so that the rest of the family would be none the wiser. And regardless, the whole scheme came to an end with the accession of Queen Victoria in 1837 — as a woman, she did not inherit the throne of Hanover, and so appointments to the Guelphic order simply passed out of British control.

June 11, 2021

June 9, 2021

June 7, 2021

Dude, where’s my (flying) car?

The latest of the reader-contributed book reviews at Scott Alexander’s Astral Codex Ten looks at Where is my Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall:

What went wrong in the 1970s? Since then, growth and productivity have slowed, average wages are stagnant, visible progress in the world of “atoms” has practically stopped — the Great Stagnation. About the only thing that has gone well are computers. How is it that we went from the typewriter to the smartphone, but we’re still using practically the same cars and airplanes?

Where is my Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall, is an attempt to answer that question. His answer is: the Great Stagnation was caused by energy usage flatlining, which was caused by our failure to switch to nuclear energy, which was caused by excessive regulation, which was caused by “green fundamentalism”.

Three hundred years ago, we burned wood for energy. Then there was coal and the steam engine, which gave us the Industrial Revolution. Then there was oil and gas, giving us cars and airplanes. Then there should have been nuclear fission and nanotech, letting you fit a lifetime’s worth of energy in your pocket. Instead, we still drive much the same cars and airplanes, and climate change threatens to boil the Earth.

I initially thought the title was a metaphor — the “flying car” as a standin for all the missing technological progress in the world of “atoms” — but in fact much of the book is devoted to the particular question of flying cars. So look at the issue from the lens of transportation:

Hans Rosling was a world health economist and an indefatigable campaigner for a deeper understanding of the world’s state of development. He is famous for his TED talks and the Gapminder web site. He classifies the wealthiness of the world’s population into four levels:

1. Barefoot. Unable even to afford shoes, they must walk everywhere they go. Income $1 per day. One billion people are at Level 1.

2. Bicycle (and shoes). The $4 per day they make doesn’t sound like much to you and me but it is a huge step up from Level 1. There are three billion people at level 2.

3. The two billion people at Level 3 make $16 a day; a motorbike is within their reach.

4. At $64 per day, the one billion people at Level 4 own a car.

The miracle of the Industrial Revolution is now easily stated: In 1800, 85% of the world’s population was at Level 1. Today, only 9% is. Over the past half century, the bulk of humanity moved up out of Level 1 to erase the rich-poor gap and make the world wealth distribution roughly bell-shaped. The average American moved from Level 2 in 1800, to level 3 in 1900, to Level 4 in 2000. We can state the Great Stagnation story nearly as simply: There is no level 5.

Level 5, in transportation, is a flying car. Flying cars are to airplanes as cars are to trains. Airplanes are fast, but getting to the airport, waiting for your flight, and getting to your final destination is a big hassle. Imagine if you had to bike to a train station to get anywhere (not such a leap of imagination for me in New York City! But it wouldn’t work in the suburbs). What if you had one vehicle that could drive on the road and fly in the sky at hundreds of miles an hour?

Before reading this book, I thought flying cars were just technologically infeasible, because flying takes too much energy. But Hall says we can and have built them ever since the 1930s. They got interrupted by the Great Depression (people were too poor to buy private airplanes), then WWII (airplanes were directed towards the war effort, not the market), then regulation mostly killed the private aviation industry. But technical feasibility was never the problem.

Hall spends a huge fraction of the book on pretty detailed technical discussion of flying cars. For example: the key technical issue is takeoff and landing, and there is a tough tradeoff between convenient takeoff/landing and airspeed (and cost, and ease of operation). It’s interesting reading. But let’s return to the larger issue of nuclear power.

May 31, 2021

The History of HSTs in the West

Ruairidh MacVeigh

Published 29 May 2021Hello again! 😀

With the recent withdrawal of the last HST operations into London, I wanted to make a series of videos chronicling the history of these mighty trains in terms of their years of each region they were assigned to, the Great Western, East Coast, Midland, West Coast and Cross Country Routes.

With that in mind, we start with the first of the BR Regions to employ the venerable HST, but also the first to withdraw them from long distance services, the Great Western, a line that, since its inception under the auspices of Brunel, has played host to many different types of trains, but none have had greater impact that the superb HSTs.

All video content and images in this production have been provided with permission wherever possible. While I endeavour to ensure that all accreditations properly name the original creator, some of my sources do not list them as they are usually provided by other, unrelated YouTubers. Therefore, if I have mistakenly put the accreditation of “Unknown”, and you are aware of the original creator, please send me a personal message at my Gmail (this is more effective than comments as I am often unable to read all of them): rorymacveigh@gmail.com

The views and opinions expressed in this video are my personal appraisal and are not the views and opinions of any of these individuals or bodies who have kindly supplied me with footage and images.

If you enjoyed this video, why not leave a like, and consider subscribing for more great content coming soon.

Thanks again, everyone, and enjoy! 😀

References:

– 125Group (and their respective sources)

– Wikipedia (and its respective references)

May 30, 2021

QotD: Pornography

The more important effect of home video — and, even more so, of the Internet — has been to create a wide and wild array of market segments, a diversity so dizzying it defies the very idea of a mainstream. A couple decades ago, feminists could argue plausibly that porn was partly responsible for the unrealistic body images they blame for bulimia and anorexia. Today, every conceivable body type has an online community of masturbators devoted to it.

Jesse Walker, “Guess Who’s Coming: Progress at the cineplex”, Reason, 2005-03-28.

May 26, 2021

May 24, 2021

QotD: The internet is rewiring our brains

… there’s a reason 99.998% of the Internet is porn, and that reason is: The Internet, itself, has rewired our brains.

Yeah, I’m a history guy, not a biologist, and no, I can’t show you the specific spots on the fMRI that prove it, but look, you can test this yourself. Ever been around kids? It’s easiest to see in the early grades, so go to a daycare or afterschool program. Trust me, you can pick out right away, with 100% accuracy, the kids who spend more than 3 hours a day at daycare. This is not a knock on daycare providers, lots of whom are good, dedicated people doing hard work. Rather, it’s a knock on the situation, because if a kid’s in daycare that long, it means the parents both work long-hour, high-stress jobs. How do you think the kid’s home life is, under those conditions?

You know as well as I do that when the kid gets home from day care, he gets plunked in front of a tv, a video game, an iPad, a smartphone, some kind of glowing box. That’s what’s rewiring their brains. That’s not “ADHD,” which doesn’t really exist. “ADHD” is a cope, a bit of shorthand, to describe what’s actually going on, which is: These kids’ heads have been rewired. They need constant stimulation. Everything needs to be in five-minute chunks for them, because they’ve never known anything different. Asking them to sit down and pay attention for any length of time – say, in a 60 minute lecture, like our old Prussian (from the 18th century!) system requires – is like asking one of us to suddenly run a marathon, or bench press 300 lbs. It can’t be done; we don’t have the equipment.

Severian, “Bio-Marxism Grab Bag”, Founding Questions, 2021-01-21.