One of my worst and most embarrassing failures as a journalist was my attempt to interview Harold Macmillan, the former British prime minister. It happened on a train near Cambridge. He was 83. I was 26. He physically fought me off, declaring in a quavering voice, “I don’t want to be interviewed; I’m much too old for that sort of thing,” as he jabbed fiercely (and quite painfully) at me with his gnarled walking stick.

Too old? Just a few years later that same wily showman drove a memorable stiletto into Margaret Thatcher’s ribs, using the same falsely quavering voice to attack her policy of selling off national assets. But I remember the humiliating occasion of my failed interview for another reason. Macmillan was able to drive me away partly because he was occupying an entire first-class compartment, reserved for him personally, on the London express. Compartments — oh, how I miss them — had sliding doors, which cut them off from the rest of the train. You could even pull the blinds down between you and the corridor. They could be marvelous private spaces for all kinds of purposes on long journeys. But you had to be lucky to get one to yourself. Once the ex-premier had driven me out, he was safe.

But Macmillan (who in those days had not given into vanity and accepted a peerage) did not have to be lucky. He had once been a director of the Great Western Railway, which had been taken into state ownership in the 1940s. So to the end of his life (in compensation for his lost power) he possessed a magical shiny token called a Gold Pass. This entitled him to free first-class travel, without limit, on any train in Great Britain. It was even rumored that it gave him the power to have trains stopped for him at stations where they did not normally halt. I often thought I would rather have such a pass than be prime minister.

Peter Hitchens, “Why I Love Trains”, First Things, 2020-07-16.

October 18, 2021

QotD: Harold Macmillan’s “Gold Pass” on British Railways

July 17, 2021

The Great Western Railway before nationalization (and back again)

In The Critic, Jonathan Glancey sings the praises of the steam locomotive designs and liveries of the pre-nationalization Great Western Railway:

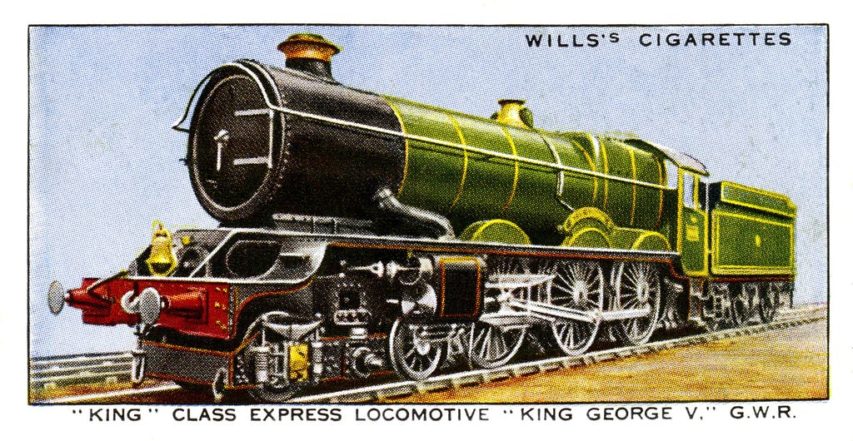

The greatest of all Great Western Railway locomotives were the King Class 4-6-0s. From 1927, and for more than 30 years, they headed principal express trains from Paddington to Bristol, Plymouth, South Wales and the West Midlands with power, precision and truly regal style.

In a livery of lined dark green with copper-capped chimneys, brass safety valve covers, and names emblazoned above their driving wheels, the Kings led long chocolate and cream-coloured trains through landscapes they enhanced in days of both private and public ownership. Together with their less powerful shed-mates — Castles, Halls, Granges and Manors — these puissant machines breathed “Great Western” with every beat of their crisp exhausts.

In the beginning, the Kings were to have been Cathedrals, an appropriate name for locomotives representing a concern that, incorporated in 1835 and engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was revered by many employees, passengers and most enthusiasts as something more akin to a religion than a mere railway. Its engineering was progressive, and yet its corporate identity (what today’s marketing jargoneers would call its “brand”) retained a gloriously ecclesiastical and slightly old-fashioned air throughout the railway’s life.

Sir William Stanier, a Great Western engineer who moved from Swindon to the LMS at Crewe and then to the chairmanship of Power Jets in the Second World War, was asked by Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis, a writer on railways, “whether there was some nameless cabal at Swindon which ruled the styling of a Great Western locomotive” from the latest 1940s designs back through the Edwardian Saints and Stars to engines of the 1880s designed by William Dean. Stanier smiled and exclaimed: “Dean? Gooch! [the GWR’s first locomotive engineer]. It was traditional.”

The tradition lives on. In 2015, today’s Great Western Railway — an operation owned by the multi-national FirstGroup — adopted a handsome dark green livery, created by the design agency Pentagram, that reaches back to the Kings and, by association, all the way to Gooch and Brunel.

The new look was sung as if from the Great Western’s “Ancient and Modern” hymn book of design. In a privatised railway world of largely gimcrack style and branding, with all too many trains looking as if their design inspiration has been that of sports shoes or the packaging of sweets such as Refreshers, the Great Western re-introduced gravitas, continuity and regional sensibility to the way its trains looked.

This is something those in charge of the newly announced Great British Railways (GBR) should think about carefully as this new public body takes over the national railway infrastructure in 2023, its remit including corporate identity. While its name is, perhaps, rather too close to Little Britain’s Great British Air, the possibility of it exercising a civilising influence over the design of our trains is there. A national design standard and identity could yet be created that speak of the unity of the British railway network and its diversity in the same breath.

May 31, 2021

The History of HSTs in the West

Ruairidh MacVeigh

Published 29 May 2021Hello again! 😀

With the recent withdrawal of the last HST operations into London, I wanted to make a series of videos chronicling the history of these mighty trains in terms of their years of each region they were assigned to, the Great Western, East Coast, Midland, West Coast and Cross Country Routes.

With that in mind, we start with the first of the BR Regions to employ the venerable HST, but also the first to withdraw them from long distance services, the Great Western, a line that, since its inception under the auspices of Brunel, has played host to many different types of trains, but none have had greater impact that the superb HSTs.

All video content and images in this production have been provided with permission wherever possible. While I endeavour to ensure that all accreditations properly name the original creator, some of my sources do not list them as they are usually provided by other, unrelated YouTubers. Therefore, if I have mistakenly put the accreditation of “Unknown”, and you are aware of the original creator, please send me a personal message at my Gmail (this is more effective than comments as I am often unable to read all of them): rorymacveigh@gmail.com

The views and opinions expressed in this video are my personal appraisal and are not the views and opinions of any of these individuals or bodies who have kindly supplied me with footage and images.

If you enjoyed this video, why not leave a like, and consider subscribing for more great content coming soon.

Thanks again, everyone, and enjoy! 😀

References:

– 125Group (and their respective sources)

– Wikipedia (and its respective references)

June 6, 2018

Travelling on British passenger trains

Other than preserved steam train passenger trips, the last time I took a train in Britain was during the “Winter of Discontent”, and it was a grim experience indeed. Recently, Malcolm Kenton purchased a First Class BritRail Pass and did some extensive travels on many of the passenger services (averaging over 250 miles per day over 12 days). He said he understands why the British complain about on-time arrivals, but compared to American passenger trains, he clearly felt he was in a railway wonderland:

10:00 PM on a Tuesday, May 15, at London’s magnificent Paddington Station. At right, a Great Western Railway

Hitachi dual-mode train has just arrived from points southwest, with a Great Western DMU train across the platform.

Photo by Malcolm Kenton

The Brits have a habit of complaining about their trains. As I experienced, their on-time performance often falls short of Swiss standards (though is excellent by American standards), ticket prices are continually increasing, and service frequencies and span on some lines aren’t what they could be. But it’s hard for someone who’s used to a country where even major cities are served by just one train a day, if that, to knock a system that provides at least three daily frequencies to even the least densely populated lines. If this is what remains after the infamous early 1960s Beeching cuts, which saw the abandonment of many secondary lines, then what existed before must have been absolutely mind-boggling.

[…]

The regular National Rail trains I rode were about evenly split between electric and diesel power. Most of the lines emanating within a 100-mile radius of London are electrified — both the East Coast and West Coast mains boast catenary as far as Edinburgh and Glasgow from London, and several other lines have third-rail power, including the South Western trains between London Waterloo and Weymouth via Southampton, which I rode — the world’s longest continuous third rail-electrified railway at 136 miles, whose electrification was completed in 1988. By contrast, America’s longest electrified railroad is only 57 miles: Metro-North’s Harlem Line from Grand Central Terminal to Southeast, N.Y. Trips of up to 200 miles on electrified lines tend to be covered by Electric Multiple Unit trainsets, while electric locomotive-hauled sets cover longer runs.

Top speeds for expresses on the electrified mains range from 100 to 125 MPH, akin to Regionals on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. Older equipment is usually limited to 80 to 90 MPH. On less busy branch lines, speeds top out between 40 and 70 MPH depending on track condition. Some of these lines are dark territory and some still use semaphore signals and manually-operated switch towers (signal boxes in British parlance).

Catenary electrification is working its way westward on the Great Western main line towards Cornwall, but long-distance expresses on this line use either 1990s-built High-Speed Train trainsets powered by diesel locomotives on both ends or two-year-old Hitachi dual-mode (catenary electric and diesel) multiple unit trainsets. Most services on less busy lines, however, are provided by Diesel Multiple Unit trainsets of varying vintages and configurations, often of just one or two cars. ScotRail’s rural services, including the five-hour run Sam and I took from Glasgow to Mallaig, all use DMUs.

Of the ten different branded National Rail services I sampled, I was most impressed with Virgin Trains, Great Western and Chiltern Railways. I took Virgin’s expresses on both the East and West Coast main lines and both offered a comfortable First Class product with hot meals and alcohol included, similar to Acela First Class. Great Western’s First Class seats were the most comfortable and the color schemes and seat arrangements the most attractive, and the food service included sandwiches as well as snacks, coffee, tea, sodas and still or sparkling water. On most trains traveling for more than one hour, there is food and beverage service from a cart. In most cases, First Class passengers get one complimentary snack (such as pretzels, fruit, crisps (potato chips in British parlance), candies, cookies and pastries) and one drink each time the cart passes through the coach.

May 14, 2012

“…but the bedrooms are in the railway carriage”

This is presented as a “bureaucracy run wild” kind of story, but I find it hard to believe that any planning committee — even a British one — would insist that a railway carriage could acquire “grandfather rights”.

When it comes to building a comfortable bungalow, Jim Higgins has got the inside track.

The retired transport manager, 60, has one of the most unique houses in Britain… because it is built around a real railway carriage.

The property in Ashton, Cornwall, is a fully functioning house but bizarrely has the fully restored 130-year-old Great Western Railway car within its walls.

Mr Higgins, 64, originally from Buckinghamshire took over the property from his former father-law Charles Allen who was forced to build it around the railway carriage because bizarre planning regulations meant the train could not be moved.

Mr Higgins said: ‘The railway carriage was lived in by a local woman Elizabeth Richards from 1930.

March 2, 2012

Britain’s railway engineering heritage

Sarah Bakewell at the Guardian on the wonderful products of the railway building era in Britain:

Once I saw merely bridges, tunnels and stations, and mostly I didn’t even notice these, so busy was I rushing to get over or through them. Now, I see a delicate ecosystem of rivets, cleats, plates, gussets, joggles, spans, arches, ribs of attenuated iron and steel.

Scholars can already study railway archives in repositories all over the country, but Network Rail has just put part of its beautiful archive of Victorian and Edwardian infrastructure diagrams on the web. This amounts to an invitation to anyone, anywhere, to contemplate such images out of sheer curiosity and love of beauty. They give us plans of the high-level bridge at Newcastle upon Tyne, with its columns trailing down the screen like tall sepia waterfalls, and Bristol’s neo-gothic Temple Meads station, in ethereal ink outline. The Forth bridge of 1890 appears side on, elongated and webby as if someone had pulled a string cat’s cradle as far as it would go. Its vertical columns climb visibly week by week; target dates are marked at each level, like the tracking of a child’s growth against a wall.

Maidenhead bridge, designed in brick by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1839, has two middle arches spanning the river in great cheetah leaps. They were lower and broader than anything previously constructed in brick, and the Great Western Railway’s directors feared the bridge would collapse: they insisted on the bridge’s temporary timber supports remaining even after it opened. Annoyed, Brunel secretly lowered the supports a bit so they did not actually support anything.

(All links in the original article.)

April 3, 2011

King Edward II restored

. . . to the rails, not the throne:

The King Edward II steam engine was first used by Great Western Railway in the 1930s, pulling trains between London Paddington and the west of England.

However, it had been left to rot in a scrapyard in Barry, Wales, until it was saved for preservation by the Great Western Society.

No 6023 King Edward II is one of only three surviving locomotives of its class, built by GWR in 1930 for taking express trains over the steep banks of South Devon.

It’s always nice to see successful restoration efforts by private groups and individuals, although this particular one drew this comment from “jackcade”:

King Edward II? The fireman better make sure he doesn’t let his poker get too hot or someone might get hurt.

Photo from the restoration website, showing the engine right after repainting:

H/T to Elizabeth for the link.