… Socialists are all about equality, and if everyone ends up equally broke, hungry, and dead, well, fair’s fair. Igor Shafarevich flat out declared that Socialism is a suicide cult. Take your pick — Socialism simply is Nihilism.

That seems bizarrely wrong, considering how much effort Socialists put into saving the world. But look at it objectively, comrade (heh heh), and you’ll see that Save-the-World-ism, of whatever flavor, always boils down to Destroy-the-World-ism. Always. It doesn’t matter how the world gets “saved;” it always gets blown up in the process. You still can’t find a better primer on chiliastic psychology than Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millennium. The specifics of each loony doctrine changed, but the underlying presumption was always the same: Kill everyone, destroy everything, and then Jesus comes.

This is true even of millennialists whose doctrines don’t obviously entail killing everyone. Calvinists, for example. I spent decades trying to explain Calvinism to undergrads, and never once succeeded. The gulf between their words and their actions is too vast for the adolescent mind. There are only two logical responses to the doctrine of “double predestination”: quietism, or hedonism. They knew it, too, which is why they started burning people at the stake the minute they got any real power. Look at what they did, not what they said, and you’ll see nihilism plain as day. Calvin’s Geneva was the nearest thing to a police state that could be achieved with 16th century technology. The ideal Calvinist would say nothing, do nothing, think nothing, as he sat in the plain pews of his unadorned chapel, waiting for death and the Final Judgment. Calvinists wanted to grind the world to a halt, not blow it up, but once again the mass extinction of the human race is a feature, not a bug.

Take Jesus out of the equation, and you end up at pure shit-flinging nihilism in less than three steps. Marxism is perhaps the most exquisitely pointless doctrine ever devised. It’s more pleasant to have than to have not, I suppose, but no matter how much everyone has, we’re still just naked apes, living the brief days of our vain lives under an utterly indifferent sky. Marxists are a special kind of stupid, so they don’t realize it, but … they won. Modern Western “poor” people keel over from heart disease while fiddling with their smartphones in front of 50″ plasma tvs. While wearing $200 sneakers. We’re so far from being “alienated” from the fruits of our labor that “labor” is an all-but-meaningless concept for lots of us — and the further down the social scale you go, the more meaningless it gets. The modern ghetto dweller simply is Marx’s ideal proletarian. Does he look self-actualized to you? Ecce homeboy.

I assure you, the SJWs know this. Calvinists to the core, they know better than anyone the utter futility of all human effort. So they do what the original Calvinists did: Displace, displace, displace. Don’t take it from me, take it from a card-carrying Marxist. The end result is the same: Whether you’re a Puritan or an SJW, the only way to escape the crushing meaninglessness of your condition is to spend every moment of every day contemplating your pwecious widdle self.

Throw in the transitive property of equality, and you’ve got people like Hillary Clinton. If Socialism is Nihilism, then Nihilism is Socialism. Far from arguing against the idea … that Hillary et al are motivated solely by hatred, I’m 100% behind it. In fact, I’d argue that the Nihilism comes first — people who have convinced themselves that life is pointless always, always, embrace the biggest and most all-encompassing form of collectivism on offer. What could be crueler, than to be given all this for nothing? It’s not even a sick joke, since a joke implies a joker.

How can you not hate this world, then, and everything in it? More to the point: how can you not hate yourself, for seeing the world as it really is? Ignorance is bliss … but how can you not hate them, too, those poor deluded motherfuckers who still think stuff like God and love and family and the designated hitter might somehow mean something? Vanity, vanity, all is vanity … and if I have to face the existential horror of it all, then fuck it, so do you. “Capitalism,” the “free market,” “representative government” — call it what you will, it’s all just vanity, just another way for the sheeple to keep deluding themselves. Fuck it, and fuck them. Burn it down. Burn it allllll down.

Severian, “A Tyranny of Nihilism”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-10-22.

November 21, 2022

November 14, 2022

QotD: The first modern revolution

The first modern revolution was neither French nor American, but English. Long before Louis XVI went to the guillotine, or Washington crossed the Delaware, the country which later became renowned for stiff upper lips and proper tea went to war with itself, killed its king, replaced its monarchy with a republican government and unleashed a religious revolution which sought to scorch away the old world in God’s purifying fire.

One of the dark little secrets of my past is my teenage membership of the English Civil War Society. I spent weekends dressed in 17th-century costumes and oversized helmets, lined up in fields or on medieval streets, re-enacting battles from the 1640s. I still have my old breeches in the loft, and the pewter tankard I would drink beer from afterwards with a load of large, bearded men who, just for a day or two, had allowed themselves to be transported back in time.

I was a pikeman in John Bright’s Regiment of Foote, a genuine regiment in the parliamentary army. We were a Leveller regiment, which is to say that this part of the army was politically radical. For the Levellers, the end of the monarchy was to be just the beginning. They aimed to “sett all things straight, and rayse a parity and community in the kingdom”. Among their varied demands were universal suffrage, religious freedom and something approaching modern parliamentary democracy.

The Levellers were far from alone in their ambitions to remake the former Kingdom. Ranters, Seekers, Diggers, Fifth Monarchists, Quakers, Muggletonians: suddenly the country was blooming with radical sects offering idealistic visions of utopian Christian brotherhood. In his classic study of the English Revolution, The World Turned Upside Down, historian Christopher Hill quotes Lawrence Clarkson, leader of the Ranters, who offered a radical interpretation of the Christian Gospel. There was no afterlife, said Clarkson; only the present mattered, and in the present all people should be equal, as they were in the eyes of God:

“Swearing i’th light, gloriously”, and “wanton kisses”, may help to liberate us from the repressive ethic which our masters are trying to impose on us — a regime in which property is more important than life, marriage than love, faith in a wicked God than the charity which the Christ in us teaches.

Modernise Clarkson’s language and he could have been speaking in the Sixties rather than the 1640s. Needless to say, his vision of free love and free religion, like the Leveller vision of universal equality, was neither shared nor enacted by those at the apex of the social pyramid. But though Cromwell’s Protectorate, and later the restored monarchy, attempted to maintain the social order, forces had been unleashed which would change England and the wider world entirely. Some celebrated this fact, others feared it, but in their hearts everyone could sense the truth that Gerard Winstanley, leader of the Diggers, was prepared to openly declare: “The old world … is running up like parchment in the fire”.

Paul Kingsnorth, “The West needs to grow up”, UnHerd, 2022-07-29.

November 5, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 8 – The Breakdown, 1025-1204

seangabb

Published 20 May 2022In this, the eighth video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, having acquired the wrong sort of ruling class, the Byzantine Empire passed in just under half a century from the hegemonic power of the Near East to a declining hulk, fought over by Turks and Crusaders.

Subjects covered include:

The damage caused by a landed nobility

The deadweight cost of uncontrolled bureaucracy

The first rise of an insatiable and all-conquering West

The failure of the Andronicus Reaction

The sack of Constantinople in 1204Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

Repost: Remember, Remember the Fifth of November

Today is the anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot:

Everyone knows what the Gunpowder Plotters looked like. Thanks to one of the best-known etchings of the seventeenth century we see them “plotting”, broad brims of their hats over their noses, cloaks on their shoulders, mustachios and beards bristling — the archetypical band of desperados. Almost as well known are the broad outlines of the discovery of the “plot”: the mysterious warning sent to Lord Monteagle on October 26th, 1605, the investigation of the cellars under the Palace of Westminster on November 4th, the discovery of the gunpowder and Guy Fawkes, the flight of the other conspirators, the shoot-out at Holbeach in Staffordshire on November 8th in which four (Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy and the brothers Christopher and John Wright) were killed, and then the trial and execution of Fawkes and seven others in January 1606.

However, there was a more obscure sequel. Also implicated were the 9th Earl of Northumberland, three other peers (Viscount Montague and Lords Stourton and Mordaunt) and three members of the Society of Jesus. Two of the Jesuits, Fr Oswald Tesimond and Fr John Gerard, were able to escape abroad, but the third, the superior of the order in England, Fr Henry Garnet, was arrested just before the main trial. Garnet was tried separately on March 28th, 1606 and executed in May. The peers were tried in the court of Star Chamber: three were merely fined, but Northumberland was imprisoned in the Tower at pleasure and not released until 1621.

[. . .]

Thanks to the fact that nothing actually happened, it is not surprising that the plot has been the subject of running dispute since November 5th, 1605. James I’s privy council appears to have been genuinely unable to make any sense of it. The Attorney-General, Sir Edward Coke, observed at the trial that succeeding generations would wonder whether it was fact or fiction. There were claims from the start that the plot was a put-up job — if not a complete fabrication, then at least exaggerated for his own devious ends by Robert Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, James’s secretary of state. The government’s presentation of the case against the plotters had its awkward aspects, caused in part by the desire to shield Monteagle, now a national hero, from the exposure of his earlier association with them. The two official accounts published in 1606 were patently spins. One, The Discourse of the Manner, was intended to give James a more commanding role in the uncovering of the plot than he deserved. The other, A True and Perfect Relation, was intended to lay the blame on Garnet.

But Catesby had form. He and several of the plotters as well as Lord Monteagle had been implicated in the Earl of Essex’s rebellion in 1601. Subsequently he and the others (including Monteagle) had approached Philip III of Spain to support a rebellion to prevent James I’s accession. This raises the central question of what the plot was about. Was it the product of Catholic discontent with James I or was it the last episode in what the late Hugh Trevor-Roper and Professor John Bossy have termed “Elizabethan extremism”?

October 31, 2022

QotD: The True Believer

A cult claimed that a flood would destroy the Earth on December 21, 1954. Only the faithful would be saved, because they’d be evacuated by a flying saucer. 12/21/54 passed without incident, of course, but what you’d expect to happen to the cult, didn’t — instead of everyone dropping out and moving on with their lives, most stayed, and their commitment to the cult’s leader actually increased.

Why? From the Wiki summary, believers will persist in the face of overwhelming disconfirmation if:

- A belief must be held with deep conviction and it must have some relevance to action, that is, to what the believer does or how he or she behaves.

- The person holding the belief must have committed himself to it; that is, for the sake of his belief, he must have taken some important action that is difficult to undo. In general, the more important such actions are, and the more difficult they are to undo, the greater is the individual’s commitment to the belief.

- The belief must be sufficiently specific and sufficiently concerned with the real world so that events may unequivocally refute the belief.

- Such undeniable disconfirmatory evidence must occur and must be recognized by the individual holding the belief.

- The individual believer must have social support. It is unlikely that one isolated believer could withstand the kind of disconfirming evidence that has been specified. If, however, the believer is a member of a group of convinced persons who can support one another, the belief may be maintained and the believers may attempt to proselytize or persuade nonmembers that the belief is correct.

This is Leftism in a nutshell, and it explains why SJWs are impervious to factual, rational argument. Boiled down as far as it will go: Group identity is so important to the Leftist that, faced with the choice between continued group membership and the evidence of xzhyr own lying eyes, xzhey will pick group membership, every time. This sets up its own feedback mechanism, such that disconfirmations of their dogmas actually increase their commitment — only the truest, holiest believers would keep believing in the face of the facts.

Severian, “What Happens if the UFO Actually Comes?”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-09-25.

October 29, 2022

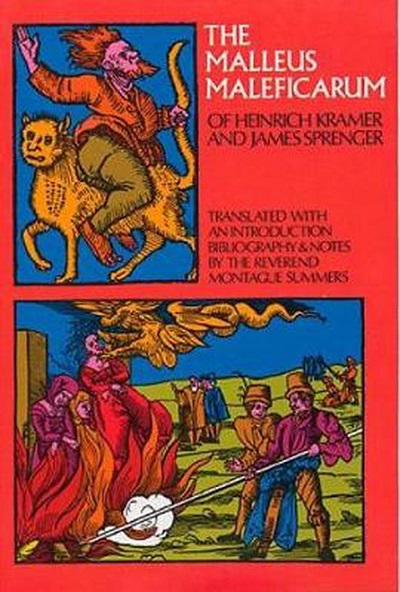

Witches, beware! It’s the Malleus Maleficarum!

It’s the season for ghosts, goblins, and — of course — witches, so Scott Alexander decided to review that famous book for witch-hunters, the Malleus Maleficarum:

Did you know you can just buy the Malleus Maleficarum? You can go into a bookstore and say “I would like the legendary manual of witch-hunters everywhere, the one that’s a plot device in dozens of tired fantasy novels”. They will sell it to you and you can read it.

I recommend the Montague Summers translation. Not because it’s good (it isn’t), but because it’s by an slightly crazy 1920s deacon every bit as paranoid as his subject matter. He argues in his Translator’s Introduction that witches are real, and that a return to the wisdom of the Malleus is our only hope of standing against them:

Although it may not be generally recognized, upon a close investigation it seems plain that the witches were a vast political movement, an organized society which was anti-social and anarchical, a world-wide plot against civilization. Naturally, although the Masters were often individuals of high rank and deep learning, that rank and file of the society, that is to say, those who for the most part fell into the hands of justice, were recruited from the least educated classes, the ignorant and the poor. As one might suppose, many of the branches or covens in remoter districts knew nothing and perhaps could have understood nothing of the enormous system. Nevertheless, as small cogs in a very small [sic] wheel, it might be, they were carrying on the work and actively helping to spread the infection.

And is this “world-wide plot against civilization” in the room with us right now? In the most 1920s argument ever, Summers concludes that this conspiracy against civilization has survived to the modern day and rebranded as Bolshevism.

Paging Arthur Miller…You can just buy the Malleus Maleficarum. So, why haven’t you? Might the witches’ spiritual successors be desperate to delegitimize the only thing they’re truly afraid of — the vibrant, time-tested witch hunting expertise of the Catholic Church? Summers writes:

It is safe to say that the book is to-day scarcely known save by name. It has become a legend. Writer after writer, who had never turned the pages, felt himself at liberty to heap ridicule and abuse upon this venerable volume … He did not know very clearly what he meant, and the humbug trusted that nobody would stop to inquire. For the most part his confidence was respected; his word was taken.

We must approach this great work — admirable in spite of its trifling blemishes — with open minds and grave intent; if we duly consider the world of confusion, of Bolshevism, of anarchy and licentiousness all around to-day, it should be an easy task for us to picture the difficulties, the hideous dangers with which Henry Kramer and James Sprenger were called to combat and to cope … As for myself, I do not hesitate to record my judgement … the Malleus Maleficarum is one of the most pregnant and most interesting books I know in the library of its kind.

Big if true.

I myself read the Malleus in search of a different type of wisdom. We think of witch hunts as a byword for irrationality, joking about strategies like “if she floats, she’s a witch; if she drowns, we’ll exonerate the corpse”. But this sort of snide superiority to the past has led us wrong before. We used to make fun of phlogiston, of “dormitive potencies”, of geocentric theory. All these are indeed false, but more sober historians have explained why each made sense at the time, replacing our caricatures of absurd irrationality with a picture of smart people genuinely trying their best in epistemically treacherous situations. Were the witch-hunters as bad as everyone says? Or are they in line for a similar exoneration?

The Malleus is traditionally attributed to 15th century theologians/witch-hunters Henry Kramer and James Sprenger, but most modern scholars think Kramer wrote it alone, then added the more famous Sprenger as a co-author for a sales boost. The book has three parts. Part 1 is basically Summa Theologica, except all the questions are about witches. Part 2 is basically the DSM 5, except every condition is witchcraft. Part 3 is a manual for judges presiding over witch trials. We’ll go over each, then return to this question: why did a whole civilization spend three centuries killing thousands of people over a threat that didn’t exist?

October 28, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 7 – Recovery and Return to Hegemony, 717-1025 AD

seangabb

Published 2 May 2022In this, the seventh video in the series, Sean Gabb explains how, following the disaster of the seventh century, the Byzantine Empire not only survived, but even recovered its old position as hegemonic power in the Eastern Mediterranean. It also supervised a missionary outreach that spread Orthodox Christianity and civilisation to within reach of the Arctic Circle.

Subjects covered:

The legitimacy of the words “Byzantine” and “Byzantium”

The reign of the Empress Irene and its central importance to recovery

The recovery of the West and the Rise of the Franks

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire

The Conversion of the Russians – St Vladimir or Vladimir the Damned?

The reign of Basil IIBetween 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or The Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

(more…)

October 25, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 6 – Weathering the Storm, 628-717 AD

seangabb

Published 16 Feb 2022In this, the sixth video in the series, Sean Gabb discusses the impact on the Byzantine Empire of the Islamic expansion of the seventh century. It begins with an overview of the Empire at the end of the great war with Persia, passes through the first use of Greek Fire, and ends with a consideration of the radically different Byzantine Empire of the Middle Ages.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)

October 19, 2022

QotD: Ritual change over time in pre-modern polytheistic religions

… if you asked a Roman or a Greek (or an Egyptian, or Mesopotamian, or what have you) how they came upon their knowledge of the gods, this would more or less be the answer: at some time in the deep past, our ancestors either figured out the correct way to keep the gods happy, or else the gods themselves delivered such a method to us (or often, some combination of the two) and we have done everything exactly that way ever since.

With the benefit of the strange sort of historical vision that lets us view multiple centuries at the same time, we can see that this is not so. Cult (by this term I don’t mean “creepy religion” I just mean “a unit of religious practice”, which is what it actually means) expands in importance or contracts. Certain gods that were seen as very important become less so and vice-versa. New practices move in, or arise seemingly out of nowhere, old practices pass out of use. And I find that also often befuddles students: so much is obviously changing, so how can these folks believe they’ve been doing everything the same since forever?

A big part of the answer is that they do not see history the way we do. For someone taking, say, a Greek history survey, you are viewing Greek society from space – zooming over entire decades, sometimes whole generations, in a single paragraph, compressing vast amounts of granularity. Change that appears rapid and obvious to us was often so slow as to be unnoticeable to people at the time – something we should remember will seem true about us when we are viewed by future humans as well.

The other thing to note is that these religious systems do allow for the idea that the gods are known imperfectly – this is another one of Clifford Ando’s excellence observations – and so the system is both devoted to tradition (if it works, keep doing it) and open to change (if it doesn’t work, innovate!). The system is thus more able to incorporate change without it seeming like anything has changed than many modern religions which have fixed religious texts with strongly accepted meanings.

Note here: it is not that the gods change, but that information about how to keep them happy can be learned. That does not produce a “newer is better” mentality though: new rituals are untested, whereas a ritual that has been practiced for centuries beyond counting has clearly worked for centuries beyond counting – after all, our society still exists and functions, so clearly, it worked!

Consequently, old practices are seen by practitioners as the best practices, but in the event of an emergency – a sudden setback that might imply the goodwill of a god (or, worse yet, the gods generally) has been lost, innovation is possible. And if that new ritual sets things right – the crisis abates – then it gets added to the portfolio of rituals-that-work, to be repeated, step for step, precisely, for future generations.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Practical Polytheism, Part I: Knowledge”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-10-25.

October 18, 2022

The War That Ended the Ancient World

toldinstone

Published 10 Jun 2022In the early seventh century, a generation-long war exhausted and virtually destroyed the Roman Empire. This video explores that conflict through the lens of an Armenian cathedral built to celebrate the Roman victory.

(more…)

October 16, 2022

The concept of “childhood” changes over time

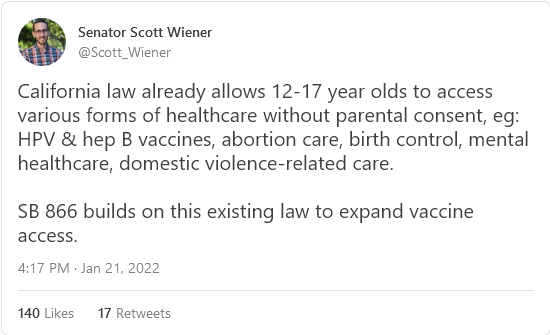

Chris Bray on the steady changes in how adult societies have viewed their children from the “better whipped than damned” views of the Puritans to the “childhood is sexy” views of today’s avante-garde opinion pushers:

Childhood is mercury.

Puritans thought that children were born in a state of profound corruption, marked by Original Sin. Infants cry and toddlers mope and disobey because they’re fallen, and haven’t had the time and the training to grow into any higher character. The devil is in them, literally. And so the first task of the Puritan parent was “will-breaking”, the act of crushing the natural depravity of the selfish and amoral infant. A child was “better whipped than damned”, in need of the firm and steady repression of his natural depravity. Proper parenting was cold and distant; parents were to instruct.

By the back half of the 19th century, children were sweet creatures, born in a state of natural innocence, until the depravity of society destroyed their gentle character. (“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”) Meanwhile, the decline of family-centered industry changed the household. The historical father, present all day on the family farm and guiding his children with patriarchal modeling and moral instruction, left for work at the factory or the office, and mom occupied “the women’s sphere“, the nurturing home.

Depraved infants, stern and firm parents; innocent children, nurturing mothers. Those two conceptions of childhood and the family can be found less than a hundred years apart at their edges. There are some other pieces to layer into that story, and see also the last thing I wrote here about the history of childhood. But the briefest version of an explanation is that the changing idea of what it meant to be a child was a reflection of growing affluence and security: Calvinist religious dissenters living hard and unstable lives viewed childhood darkly, while the apotheosis of Romantic childhood appeared in the homes of the emerging Victorian management class.

So childhood is mercury: It moves and morphs with societal changes, becoming a different thing in different cultures and economies. It tells you what the temperature is.

In the febrile cultural implosion of 2022, childhood is sexy, and legislators work hard to make sure 12 year-olds can manage their STDs without the interference of their stupid clingy parents.

Or click on this link to see a fun story about a teacher in Alabama who has a sideline as a drag queen, reading a story to young children about a dog who digs up a bone and then cleverly telling the children, “Everybody loves a big bone.” Wink wink! I mean, really, what could be sexier or more fun than talking to very young children about thick adult erections, amirite?

Update: Corrected link.

October 14, 2022

That time that H.G. Wells fell afoul of Muslim sentiments

In the New English Review, Esmerelda Weatherwax recounts an incident from the 1930s where Muslim protestors took to the streets of London in reaction to a recent Hindustani translation of H.G. Wells’ A Short History of the World:

Screen capture of the 1938 Muslim protest march in London from a British Pathé newsreel – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ADausiEe4pM

… my husband was at the Museum of London and spotted a very brief mention of this protest in 1938 on a list of 20th century London events. I did some research.

The book they objected to was HG Wells’ A Short History of the World. This was originally published in 1922 but in 1938 an abridged version was tranlated into Hindustani and published in India. His observations about the Prophet Mohammed did not find favour with Indian Muslims (and as you know pre-partition the area called India covered what is now Pakistan and Bangladesh). There were protest meetings in Calcutta and Mumbai (then transliterated as Bombay) and the consignments of the books that WH Smith the booksellers sent to Hyderabad mysteriously never arrived. Investigation showed that the Sind government banned its import. Protests spread to east Africa and were reported in Nairobi and Mombasa.

The paragraphs concerned said “He seems to have been a man compounded of very considerable vanity, greed, cunning, self-deception, and quite sincere religious passion”. Wells concludes, not unfavourably, that “when the manifest defects of Muhammad’s life and writing have been allowed for, there remains in Islam, this faith he imposed upon the Arabs, much power and inspiration”.

There had been a number of Muslims living in east London for some years, sailors who came through the docks, retired servants, some professional men and in 1934 they formed a charitable association for the promotion of Islam called Jamiat-ul-Muslimin; they met on Fridays at a hall in Commercial Road.

On Friday 12th August 1938 a copy of A Short History of the World was, as apparently reported in the Manchester Guardian the following day “ceremoniously burned”. The main Nazi book burnings were over 5 years previously but I can’t but be reminded of them. I can’t access the Guardian on-line archive for 1938 as I don’t have a subscription, but I have no reason to doubt what they reported.

A few days later Dr Mohammed Buksh of Jamiat-ul-Muslimin attended upon Sir Feroz Khan Noon, the high commissioner for India. Sir Feroz tried to explain that in Britain we could (or could then) freely criticise Christianity, the Royal family and government as a right. He reminded Dr Buksh that Muslims were “a very small minority in England, and it would do them no good to try and be mischievous in this country, no matter how genuine their grievances were”.

October 5, 2022

Are the protests in Iran about to tip over into actual revolution?

In The Line, Kaveh Shahrooz reports on the still-ongoing public protests after the death of a young woman at the hands of the morality police:

Aftermath of anti-government protests in Bojnord, North Khorasan Province, Iran, 22 September, 2022.

Photo from Tasnim News Agency Bojnord Desk via Wikimedia Commons.

Revolutions are funny things. They sometimes appear impossible until, in one single moment, they become inevitable. In Iran, that moment came on September 13th with the murder of a young woman.

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old who was also known by her Kurdish name “Gina”, had come from Iran’s Kurdistan region to visit her brother in Tehran. It was during that trip that she faced a particular humiliation that has become a fact of life for tens of millions of women in that country: a run-in with the country’s gasht-e ershad (“Guidance Patrol”). The role of this roving gang, seemingly imported from Atwood’s Gilead and called Iran’s “morality police”, is to monitor the streets to find and punish violations of the regime’s seventh-century moral and dress codes.

Having determined that Mahsa’s hijab exposed a little too much hair — a few strands of a woman’s hair and men will simply be incapable of controlling their sexual urges, the logic goes — they detained and beat her severely. The story for most women who deal with the morality police typically ends there, after which they are released to seethe at having endured another round of state-imposed gender apartheid. For Mahsa, the story ended differently: with a skull fracture that caused her to be brought, brain dead, to a local clinic. She died there on September 16th.

The murder of Mahsa Amini was the spark that set off a revolution. The killing reminded women of their daily misery at the hands of a regime that, both de facto and de jure, treats them as second-class citizens. And it reminded everyone of the million other senseless cruelties, large and small, that they must endure daily at the hands of a barbaric theocracy. Outraged by the death of an innocent young woman, the people took to the streets in protests that continue to this day.

There have been mass protests in Iran before. In 2009, in response to a widespread belief that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had illegally stolen the presidential election — to the extent the word “election” means anything in a country where candidates must first be approved by a clerical body loyal to the regime — citizens protested by the millions. Their slogan, “Where’s my vote?” rested on the premise that a fair, albeit controlled, election was something that could change the system for the better. The protesters typically avoided confrontation with security forces. Even when they happened to corner a regime thug periodically, they ensured that no harm was done to him.

September 30, 2022

History Re-Summarized: The Roman Empire

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 16 Sept 2022

The plot twist of Rome is that it was always a mess, now sit back and enjoy the marble-covered mayhem.This video is a Remastered, Definitive Edition of three previous videos from this channel — “History Summarized: The Roman Empire”, “History Hijinks: Rome’s Crisis of the Third Century”, and “History Summarized: The Fall of Rome”. This video combines them all into one narrative, fully upgrading all of the visuals and audio, with a substantially re-written script in parts 1 and 3.

(more…)

September 29, 2022

The Byzantine Empire: Part 5 – The Death of Roman Byzantium, 568-628 AD

seangabb

Published 21 Jan 2022In this, the fifth lecture in the series, Sean Gabb discusses the progressive collapse of Byzantium between the middle years of Justinian and the unexpected but sterile victory over the Persian Empire.

Between 330 AD and 1453, Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was the capital of the Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Later Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire, the Mediaeval Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire. For most of this time, it was the largest and richest city in Christendom. The territories of which it was the central capital enjoyed better protections of life, liberty and property, and a higher standard of living, than any other Christian territory, and usually compared favourably with the neighbouring and rival Islamic empires.

The purpose of this course is to give an overview of Byzantine history, from the refoundation of the City by Constantine the Great to its final capture by the Turks.

Here is a series of lectures given by Sean Gabb in late 2021, in which he discusses and tries to explain the history of Byzantium. For reasons of politeness and data protection, all student contributions have been removed.

(more…)