One particular feature of Rome’s system of magistrates is that the offices were organized from a relatively early point into a “career path” called the cursus honorum or “path of honors”. Now we have to be careful here on a few points. First, our sources tend to retroject the cursus honorum back to the origins of the republic in 509, but it’s fairly clear in those early years that the Romans are still working out the structure of their government. For instance our sources are happy to call Rome’s first magistrates in the early years “consuls“, but in fact we know1 that the first chief magistrates were in fact praetors. Then there is a break in the mid-400s where the chief executive is vested briefly in a board of ten patricians, the decemviri. This goes poorly and so there is a return to consuls, soon intermixed from 444 with years in which tribuni militares consulari potestate, “military tribunes with consular powers”, were elected instead (the last of these show up in 367 BC, after which the consular sequence becomes regular). Charting those changes is difficult at best because our own sources, writing much later, are at best modestly confused by all of this. I don’t want to get dragged off topic into charting those changes, so I’ll just once again commend the Partial Historians podcast which marches through the sources for this year-by-year. The point here is that this system emerges over time, so we shouldn’t project it too far back, though by 367 or so it seems to be mostly in place.

The second caution is that the cursus honorum was, for most of its history, a customary thing, a part of the mos maiorum, rather than a matter of law. But of course the Romans, especially the Roman aristocracy, take both the formal and informal rules of this “game” very seriously. While unusual or spectacular figures could occasionally bend the rules, for most of the third and second century, political careers followed the rough outlines of the cursus honorum, with occasional efforts to codify parts of the process in law during the second century, beginning with the Lex Villia in 180 BC, but we ought to understand that law and others of the sort as mostly attempting to codify and spell out what were traditional practices, like the generally understood minimum ages for the offices, or the interval between holding the same office twice.

That said, there is a very recognizable pattern that was in some cases written into law and in other cases merely customary (but remember that Roman culture is one where “merely customary” carries a lot of force). Now the cursus formally begins with the first major office, the quaestorship, but there are quite a few things that an aspiring Roman elite needs to do first. The legal requirement is that our fellow – and it must be a fellow, as Roman women cannot hold office (or vote) – needs to have completed ten years of military service (Polyb. 6.19.1-3). But there are better and worse ways to discharge this requirement. The best way is being appointed as junior officers, military tribunes, in the legions. We’ll talk about this office in a bit, but during this period it served both as a good first stepping stone into political prominence as well as something more established Roman politicians did between major office-holding, perhaps as a way of remaining prominent or to curry favor with the more senior politicians they served under or simply because military exigency meant that more experienced hands were wanted to lead the army.

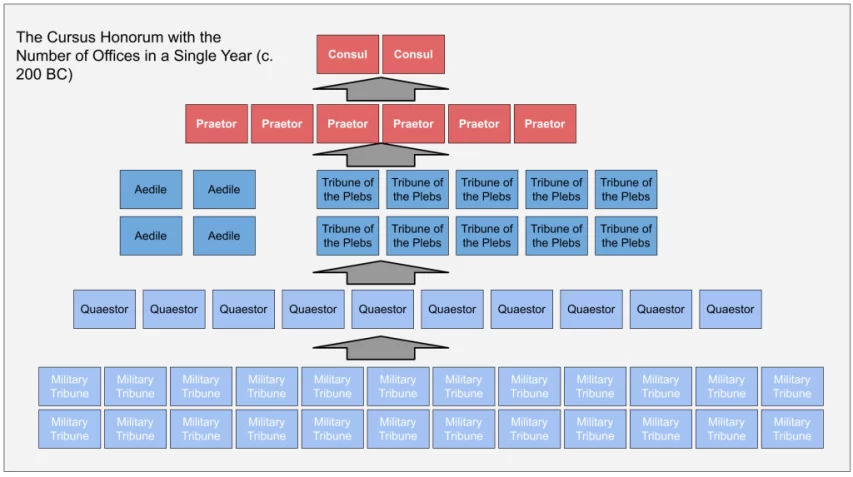

A diagram of the elected offices of the cursus honorum. Note that there were additional appointed military tribunes.

There are a bunch of other minor magistrates that are effectively “pre-cursus” offices too, but we don’t know a lot about them and they don’t seem generally to show up as often in the careers of the sort of Romans making their way up to the consulship, though this may be simply because our sources don’t mention them as much at all and so we simply don’t know who was holding them in basically any year. We’ll talk about them at the end of this set of posts, because they are important (particularly for non-elites).

I should note at the outset: all of these offices are elected annually unless otherwise noted, with a term of service of one year. You never hold the same office twice until you reach the consulship, at which point you can seek re-election, after a respectable delay (which is later codified into law and then ignored), but you may serve as a military tribune several times (this was normal, in fact, as far as we can tell).

The first major office of the cursus was the quaestorship. The number of quaestors elected grows over time. Initially just two, their number is increased to four in 421 (two assigned to Rome, one to each of the consuls) and then to six in the 260s (initially handling the fleet, then later to assist Roman praetors or pro-magistrates in the provinces) and then eight in 227. There may have been two more added to make ten somewhere in the Middle Republic, but recent scholarship has cast doubt on this, so the number may have remained eight until being expanded to twenty under Sulla in 81 BC through the aptly named lex Cornelia de XX quaestoribus (the Cornelian Law on Twenty Quaestors, Sulla being Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix).2 It’s not clear if there was a legal minimum age for the quaestors and we only know the ages of a few (25, 27, 29 and 30, for the curious) so all we can say is that officeholders tended to hold the office in their twenties, right after finishing their mandatory stint of military service.3 Serving as a quaestor enables entrance into the Senate, though one has to wait for the next census to be added to the Senate rolls by the censors.

After the quaestorship, aspirants for higher office had a few options. One option was the office of aedile; there were after 367 four of these fellows. Two were plebeian aediles and were not open to patricians, while the two more prestigious spots were the “curule” aediles, open to both patricians and plebeians. The other option at this stage for plebeian political hopefuls was to seek election as a tribune of the plebs, of which there were ten annually, we’ll talk about these fellows in a later post because they have wide-ranging, spectacular and quite particular powers.

After this was the praetorship, the first office which came with imperium. Initially there may have just been one praetor; by the 240s there are two (what will become the praetor urbanus and the praetor peregrinus). In 227 the number increases to four, with the two new praetors created to handle administration in Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. That number then increases to six in 198/7, with the added praetors generally being sent to Spain. Finally Sulla raises the number to eight in 81 BC. The minimum age seems to have been 39 for this office.

Finally comes the consulship, the chief magistrate of the Roman Republic, who also carried imperium but of a superior sort to the praetors. There were always two consuls and their number was never augmented. For our period (pre-Sulla) the consuls led Rome’s primary field armies and were also the movers of major legislation. Achieving the consulship was the goal of every Roman embarking on a political career. This is the only office that gets “repeats”.

Finally there is one office after the cursus honorum and that is the censorship. Two are elected every five years for an 18 month term in which they carry out the census. Election to the censorship generally goes to senior former-consuls and is one way to mark a particularly successful political career. That said, Romans tend to dream about the consulship, not the censorship and if you had a choice between being censor once or holding the consulship two or three times, the latter was more prestigious.

With the offices now laid out, we’ll go through them in rough ascending sequence. Today we’ll look at the military tribunes, the quaestors and the aediles; next week we’ll talk about imperium and the regular offices that carry it (consuls, praetors and pro-magistrates). Then, the week after that, we’ll look at at two offices with odd powers (tribunes of the plebs and censors), along with minor magistrates. Finally, there’s another irregular office, that of dictator, which we have already discussed! So you can go read about it there!

One thing I want to note at the outset is the “elimination contest” structure of the cursus honorum. To take the situation as it stands from 197 to 82, there are dozens and dozens of military tribunes, but just eight quaestors and just six praetors and then just two consuls. At each stage there was thus likely to be increasingly stiff competition to move forward. To achieve an office in the first year of eligibility (in suo anno, “in his own year”) was a major achievement; many aspiring politicians might require multiple attempts to win elections. But of course these are all annual offices, so someone trying again for the second or third time for the consulship is now also competing against multiple years of other failed aspirants plus this new year’s candidates in suo anno. We’ll come back to the implications of this at the end but I wanted to note it at the outset that even given the relatively small(ish) size of Rome’s aristocracy, these offices are fiercely competitive as one gets higher up.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How to Roman Republic 101, Part IIIa: Starting Down the Path of Honors”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-08-11.

1. See Lintott, op. cit. 104-5, n. 47.

2. These dates and numbers, by the by, follows F.P. Polo and A.D. Fernández, The Quaestorship in the Roman Republic (2019).

3. If you are wondering about how anyone can manage to hold the office before 27, given ten years of military service and 17 being the age when Roman conscription starts, well, we don’t really know either. The best supposition is that some promising young aristocrats seem to have started their military service early, perhaps in the retinues (the cohors amicorum) of their influential relatives. Tiberius Gracchus at 25 is the youngest quaestor we know of, but he’s in the army by at most age 16 with Scipio Aemilianus at Carthage in 146.

May 27, 2024

QotD: The Cursus Honorum in the Roman republic

May 26, 2024

QotD: Ever-expanding government

Where government advances — and it advances relentlessly — freedom is imperiled; community impoverished; religion marginalized and civilization itself jeopardized … When did government cease to be a necessary evil and become a goody bag to solve our private problems?

Janice Rogers Brown, “Hyphenasia: the Mercy Killing of the American Dream,” Speech at Claremont-McKenna College (Sept. 16, 1999).

May 25, 2024

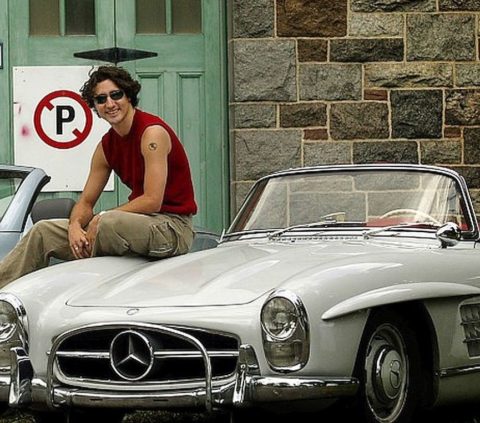

Justin Trudeau – “a large percentage of small businesses are actually just ways for wealthier Canadians to save on their taxes”

Even before he became Prime Minister, the signs were there that Justin Trudeau was instinctively anti-small-business and that this would inform his approach to taxation and regulation of the private sector:

Changes to capital gains tax in this year’s budget were aimed at the wealthy, said the Trudeau Liberals, but the move has angered small businesses owners who have been snared by the increase.

Maybe that was part of the plan, since Justin Trudeau appears to view small business owners as rich Canadians trying to dodge taxes.

In an illuminating interview with the CBC’s Peter Mansbridge in 2015, Trudeau didn’t directly answer a question about whether he would lower taxes for small businesses.

But he did say, “We have to know that a large percentage of small businesses are actually just ways for wealthier Canadians to save on their taxes and we want to reward the people that are actually creating jobs and contributing in concrete ways.”

It was a remarkable denigration of small business owners and may have passed unnoticed because Trudeau was still a month away from becoming prime minister.

For the record, businesses with fewer than 100 people employ almost 12 million private workers in this country.

And the government’s own statistics state that in the 20 years up to 2020, the number of small businesses increased every year except for three — 2013, 2016 and 2020 — so a decrease in two of the Trudeau years.

Meanwhile, Trudeau’s apparently tax-dodging wealthy small businesses seem to be having a hard time of it. Businesses that began with four or less employees were only 62 per cent likely to still be operating five years later.

Earlier this year, Reuters news agency warned that a 38 per cent spike in bankruptcies of small businesses in the first 11 months of 2023 could rise even further.

Small businesses are “an integral engine of Canada’s economy,” said the budget, but 72 per cent of the owners fear that the new changes to capital gains tax will harm the climate for investment and growth.

Interestingly, when Trudeau was asked in that 2015 interview how he planned to balance the budget by 2019, because that was what he promised, it was investment and growth that was the answer.

Then prime minister Stephen Harper had tried to cut his way out of the deficit, said Trudeau. “That doesn’t work.”

“He has been unable to create growth. He has the worst record on growth of any prime minister in 80 years.”

But as the Fraser Institute has pointed out, in the last nine years under Trudeau, Canadian living standards have declined.

May 24, 2024

Bernie Sanders finally finds a group of rich people who he thinks shouldn’t have to pay

As Tim Worstall points out, Bernie Sanders’ latest campaign is starkly at odds with his usual “make the rich pay” schtick:

“Bernie Sanders” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

It’s possible to think that Bernie Sanders, Senator that he is, is more than a little confused. Well, he’d not be the first elderly politician to suffer that fate. Nor the first socialist. It is necessary for me to be fair here though — one of his honeymoons he took in the Soviet Union. Which makes perfect sense to me — after all, there was bugger all else to do there other than your own wife.

However, here we’ve got him complaining about the cost of the new miracle drugs:

Bernie Sanders has urged Denmark to rein in its most valuable company, Novo Nordisk, and force it to slash prices on popular weight loss and diabetes treatments Ozempic and Wegovy, taking his fight to lower “outrageously high” drug prices in the United States to the company’s doorstep as its profits soar amid ongoing struggles to meet booming appetite for the revolutionary drugs.

Hmm, dunno how well that’s going to work with the Danes really. Yes, to some extent they’re milder than when they tried to rape and pillage the entirety of Europe but not wholly. My brother worked out in Afghanistan (feeding the troops) and he had a Danish unit rotate through. So he tells me their senior sergeant type carried a double bladed axe on his backpack — it didn’t come back clean from every patrol either. They’re not all equality and gender rights these days, you know?

So, we can imagine a certain portion at least of the Danish population celebrating this rapine of Medicare’s pockets by the simple expedient of selling a weight loss drug that actually works — which is, when we come to think of it, something of an innovation. Fen-Fen didn’t work after all. Hey, you know, Vinland failed but we’ll get ’em this time? We’re charging high prices because we can?

A second pass at the argument would be that the drugs are in fact incredibly cheap. When it was shown that the same drug — semaglutide — works in stopping (that’s “stopping” as in ceased, stopped, dead, like Bernie’s career would if it were ever proven he had taken part in an act of voluntary capitalism) chronic kidney disease. So much so that the very day they announced the trials on the drug were being stopped a year early, so obvious was the success, the share prices of all the dialysis provision companies dropped 20 and 30%. That is, at near whatever price, this drug is a money saver. Which is, you know, good. J Foreigner turns up with this thing that saves America, Americans, lives and money and yet Bernie whines — so like a socialist, eh? Capitalism with markets makes us the humans who are living highest on the hog, ever, but they really never do stop whining about it, do they?

But Bernie’s real complaint is that Americans are paying more to burn off the cheeseburgers than everyone else has to. But from everything else Bernie says about anything at all this is at it should be — the rich should pay.

Back to our basics. The basic drug development problem is that the development of a drug is a public goods problem. It costs $2 billion to get a drug through the FDA and gain approval to actually sell it. Yes, of course we should slaughter much of the regulation that makes it cost that much (personally, against character type, I only recommend capture and humane release for the actual bureaucrats) but that’s another matter. It does. But if everyone can just copy the drug at that point then no one will spend $2 billion. So, OK, patents, so the developers have a decade (the patent is two decades, it takes a decade to gain approval) to make their $2 billion back then anyone can copy it. The price falls to manufacturing cost plus normal profit level and we’re about as good as we can get. This is not a perfect system but for mass market drugs it’s about as good as we’re going to get.

May 23, 2024

“[O]fficial justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them”

While it sometimes seems that there can’t possibly be mass migration issues other than here in Canada and along the US southern border, eugyppius reminds us that all of the Kakistocrats in western countries are fully in favour of more, and more, and even more inflow without restriction:

An asylum seeker, crossing the US-Canadian border illegally from the end of Roxham Road in Champlain, NY, is directed to the nearby processing centre by a Mountie on 14 August, 2017.

Photo by Daniel Case via Wikimedia Commons.

You might have noticed that mass migration to the West is a huge problem.

It is very bad for native Westerners, because it promises to transform our societies utterly, in permanent ways and not for the better. Curiously, it is also far from great for the centre-left political establishment responsible for promoting mass migration, because it has inspired a vast wave of popular opposition and filled the sails of right-leaning, migration restrictionist parties with new wind. Mass migration is also bad for taxpayers, for domestic security, for the welfare state, for many other aspects of the postwar liberal agenda and for our own future prospects. In short, mass migration is bad for almost everybody and everything.

There is a reason that nations have borders, and this is much the same reason that we have skin and that cells have membranes. You won’t survive for very long if you can’t control what enters you.

Despite the obvious fact that mass migration is bad, our rulers cling to migrationism like grim death. Given a choice between disincentivising asylees and intimidating, browbeating and harassing the millions of anti-migrationists among their own citizens, our governments generally choose the latter path, even though it is obviously the worse of the two.

Additionally unsettling, is the fact that official justifications for mass migration often have a creepy, post-hoc flavour about them. They sound much more like excuses dreamed up after the borders had already been opened, rather than any kind of reason mass migration must occur. When the migrationists really started to go crazy in 2015, for example, we were told that border security was simply impossible in the modern world and that infinity migrants were a force of nature we would have to deal with. That didn’t sound right even at the time, and since the pandemic border closures we no longer hear the inevitability narrative very much, although – and this is very bizarre to type – there is some evidence that high political figures like Angela Merkel believed it at the time. It is well worth thinking about why that might have been the case.

Another excuse that doesn’t make very much sense, is what I’ll call the refugee thesis. We’re told that millions of poor people are forced to endure terrible conditions in the developing world and that it is our moral burden to improve their lot by granting them residence in our countries. That might convince a few teenage girls, but it cannot withstand scrutiny among the rest of us. To begin with, the population of global unfortunates is enormous; the millions of refugees we have already accepted, and the millions that our politicians hope to welcome in the coming years, represent but a vanishing minority – a rounding error – compared to the vast sea of human suffering. It is like trying to solve homelessness by demanding that those in the wealthiest neighbourhoods make their spare bedrooms available to the indigent. Even more telling, however, is that the push to welcome migrants comes precisely as conditions in the developing world have dramatically improved. When things were much worse, we sealed our borders against the global south; now that they are much better, we hear all about how unacceptably inhumane it is to leave the migrants in their native lands.

Other post-hoc arguments, especially those falling in the yay-multiculturalism category, are even less serious. That we need more diversity to “spark innovation” (whatever that means) or that our local cuisines stand to benefit from the spices of the disadvantaged, are excuses of such towering stupidity, that you will lose brain cells thinking about them. As with the refugee narrative, nobody said crazy stuff like this until the migrants had already begun arriving on our shores. And there is another thing to notice about the multiculticult too. This is its blatant flippancy. The premise seems to be that migration is no big deal bro, but also too there are these cool exciting and totally random upsides, like improved local Ethiopian food offerings. It is the very definition of damning with faint praise.

The rest, sadly, is behind the paywall.

The “post-national” entity formerly known as “Canada”

You have to hand it to the Trudeau family (and all their sycophantic enablers in the legacy media, of course). What other Canadian family has had such an impact on the country? By the time Justin Trudeau’s successor is invited to form a government, Canada will have changed so much — to the point that he could describe us as the first “post-national” country thanks to his unceasing effort to destroy the nation. At The Hub, Eric Kaufmann points the finger at Trudeau’s “Liberal-left extremism” as the motivating factor in Trudeau’s career:

Justin Trudeau has always had a strong affinity for the symbolic gesture, especially when the media are around to record it.

Canada is currently suffering from left-liberal extremism the likes of which the world has never seen. This excess is not socialist or classically liberal, but specifically “left-liberal”. It is evident in everything from this country’s world record immigration and soaring rents to state-sanctioned racial discrimination in hiring and sentencing, to the government-led shredding of the country’s history and memory. Rowing back from this overreach will not be the work of voters in one election, but of generations of Canadians.

The task is especially difficult in Canada, because, after the 1960s, the country (outside of Quebec) transferred its soul from British loyalism to cultural left-liberalism. Its new national identity (multiculturalist, post-national, with no “core” identity) was based on a quest for moral superiority measured using a left-liberal yardstick. Canada was to be the most diverse, most equitable, most inclusive nation in world history. No rate of immigration, no degree of majority self-abasement, no level of minority sensitivity, would ever be too much.

In my new book The Third Awokening, I define woke as the making sacred of historically marginalized race, gender, and sexual identity groups. Woke cultural socialism, the idea of equal outcomes and emotional harm protection for totemic minorities, represents the ideological endpoint of these sacred values. Like economic socialism, the result of cultural socialism is immiserization and a decline in human flourishing. We must stand against this extremism in favour of moderation.

The woke sanctification of identity did not stem primarily from Marxism, which rejected identity talk as bourgeois, but from a fusion of liberal humanism with the New Left’s identitarian version of socialism. What it produced was a hybrid which is neither Marxism nor classical liberalism.

Left-liberalism is moderate on economics, favouring a mixed capitalism in which regulation and the welfare state ameliorate the excesses of the market, without strangling economic growth. Its suspicion of communist authoritarianism helped insulate it from the lure of Soviet Moscow.

On culture, however, left-liberalism has no guardrails. When it comes to group inequality and harm protection, its claims are open-ended, with institutions and the nation castigated as too male, pale, and stale. For believers, the only way forward is through an unrestricted increase in minority representation. They will not entertain the idea that the distribution of women and minorities across different occupations could reflect cultural or psychological diversity as opposed to “systemic” discrimination. This is the origin of the letters “D” and “E” in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). Rather than seeking to optimize equity and diversity for maximal human flourishing, these are ends in themselves that brook no limits.

Left-liberals fail to ring-fence the degree of sensitivity that majority groups are supposed to display toward minority groups. Their emphasis on inclusivity through speech suppression rounds out the “I” in DEI. From racial sensitivity training (starting in the 1970s) to the “inclusive” avoidance of words like “Latino” or “mother” that offend and create a so-called hostile environment that silences subaltern groups, majorities are expected to police their speech.

May 22, 2024

If you re-define it carefully, you can make any statistical measure look hopeful

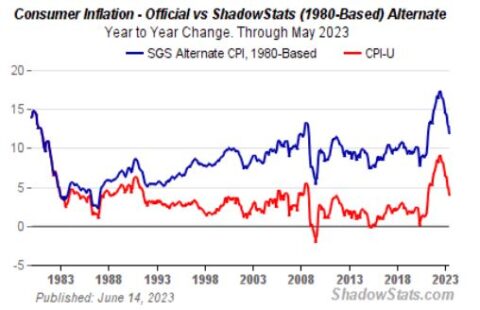

In his Substack, Tim Worstall jokingly called this piece “Larry Summers Explains Why Americans Hate Joe Biden”:

As a good Democrat of course Larry Summers would never put things in quite that headline way. But the implication of this latest paper with others is to explain why Americans really aren’t as happy as they should be given the economic numbers. The answer being that the economic numbers we all look at to explain how happy folk are aren’t the right economic numbers to explain how happy people are.

We can also make — possibly rightly, possibly wrongly, this might be me projecting more than is merited — a further claim. That Americans simply aren’t as rich as those standard economic numbers suggest either. Which would also neatly explain the general down in the dumps attitude toward the economy.

So, the new paper:

Unemployment is low and inflation is falling, but consumer sentiment remains depressed. This has confounded economists, who historically rely on these two variables to gauge how consumers feel about the economy. We propose that borrowing costs, which have grown at rates they had not reached in decades, do much to explain this gap. The cost of money is not currently included in traditional price indexes, indicating a disconnect between the measures favored by economists and the effective costs borne by consumers. We show that the lows in US consumer sentiment that cannot be explained by unemployment and official inflation are strongly correlated with borrowing costs and consumer credit supply. Concerns over borrowing costs, which have historically tracked the cost of money, are at their highest levels since the Volcker-era. We then develop alternative measures of inflation that include borrowing costs and can account for almost three quarters of the gap in US consumer sentiment in 2023. Global evidence shows that consumer sentiment gaps across countries are also strongly correlated with changes in interest rates. Proposed U.S.-specific factors do not find much supportive evidence abroad.

OK, or as explained by the Telegraph:

In it, the authors made a shocking claim: if inflation was measured in the same way that it was measured during the last bout of price rises in the 1970s, data showed that it peaked at 18pc in November 2022. This is far higher than the 9.1pc peak inflation shown by the official data.

The reason for this discrepancy is that, since the 1970s, economists have removed the cost of borrowing from the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The motivations here were not nefarious. The reasoning of the statisticians had something to it.

And, OK, if inflation peaked at 18%, not 9%, then that would explain why folk are pissed. Sure it would.

[…]

OK. But that means that if inflation was higher than we’ve been using then the deflation of nominal to real GDP is also wrong. Just that one year of 9% recorded but 18% by this new measure is damn near a 10% difference. That’s how much we’re over-estimating real GDP by right now. Add in a couple of years of lower levels of that and being 20% out wouldn’t surprise.

Which would mean that — if this were true and I might be overegging it — Americans are in fact 20% poorer than the Biden Admin keeps saying they are. And yes, that would piss the voters off, wouldn’t it?

Gaslighting has been a staple of the legacy media for quite some time now, going into high gear during the 2016 US Presidential elections and then into overdrive during the pandemic. They probably don’t even realize they’re doing it any more, because it feels “normal” to them. Yet they wonder why their popularity and public trust in their pronouncements continues to drop.

The new queen of the AWFLs

Elizabeth Nickson on the rise of new NPR CEO, Katherine Maher:

Banner for Christopher Rufo’s article on Katherine Maher at City Journal.

https://christopherrufo.com/p/katherine-mahers-color-revolution

The polite world was fascinated last month when long-time NPR editor Uri Berliner confessed to the Stalinist suicide pact the public broadcaster, like all public broadcasters, seems to be on. Formerly it was a place of differing views, he claimed, but now it has sold as truth some genuine falsehoods like, for instance, the Russia hoax, after which it covered up the Hunter Biden laptop. And let’s not forget our censor-like behaviour regarding Covid and the vaccine. NPR bleated that they were still diverse in political opinion, but researchers found that all 87 reporters at NPR were Democrats. Berliner was immediately put on leave and a few days later resigned, no doubt under pressure.

Even more interesting was the reveal of the genesis of NPR’s new CEO, Katherine Maher, a 41-year-old with a distinctly odd CV. Maher had put in stints at a CIA cutout, the National Democratic Institute, and trotted onto the World Bank, UNICEF, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Center for Technology and Democracy, the Digital Public Library of America, and finally the famous disinfo site Wikipedia. That same week, Tunisia accused her of working for the CIA during the so-called Arab Spring. And, of course, she is a WEF young global leader.

She was marched out for a talk at the Carnegie Endowment where she was prayerfully interviewed and spouted mediatized language so anodyne, so meaningless, yet so filled with nods to her base the AWFULS (affluent white female urban liberals) one was amazed that she was able to get away with it. There was no acknowledgement that the criticism by this award-winning reporter/editor/producer, who had spent his life at NPR had any merit whatsoever, and in fact that he was wrong on every count. That this was a flagrant lie didn’t even ruffle her artfully disarranged short blonde hair.

Christopher Rufo did an intensive investigation of her career in City Journal. It is an instructive read and illustrative of a lot of peculiar yet stellar careers of American women. Working for Big Daddy is apparently something these ghastly creatures value. I strongly suggest reading Rufo’s piece linked here. It’s a riot of spooky confluences.

Intelligence has been embedded in media forever and a day. During my time at Time Magazine in London, the bureau chief, deputy bureau chief and no doubt the “war and diplomacy” correspondent all filed to Langley and each of them cruised social London ceaselessly for information. Tucker Carlson asserted on his interview with Aaron Rogers this week that intelligence operatives were laced through DC media and in fact, Mr. Watergate, Bob Woodward himself, had been naval intelligence a scant year before he cropped up at the Washington Post as “an intrepid fighter for the truth and freedom no matter where it led”. Watergate, of course, was yet another operation to bring down another inconvenient President; at this juncture, unless you are being puppeted by the CIA, you don’t get to stay in power. Refuse and bang bang or end up in court on insultingly stupid charges. As Carlson pointed out, all congressmen and senators are terrified by the security state, even and especially the ones on the intelligence committee who are supposed to be controlling them. They can install child porn on your laptop and you don’t even know it’s there until you are raided, said Carlson. The security state is that unethical, that power mad.

Now, it’s global. And feminine. Where is Norman Mailer when you need him?

QotD: Are western democracies moving uniformly in the direction of “surface democracy”?

I joked before about refusing to tolerate speculation about the US being a surface democracy like Japan, but joking aside I think even the staunchest defender of the reality of popular rule would concede that things have moved in that direction on the margin. Compare the power of agency rulemaking, federal law enforcement, spy agencies, or ostensibly independent NGOs now to where they were even 10 years ago. It would be a stretch to say that the electorate didn’t have influence over the American state, but can they really be said to rule it? Regardless of exactly where you come down on that question, it’s probably safe to say that you’d give a different answer today than you would have twenty, fifty, or a hundred years ago. Moreover, the movement has been fairly monotonic in the direction of less direct popular control over the government. And in fact this phenomenon is not unique to the United States, but reappears in country after country.

Is there something deeper at work here? There’s a theory, popular among the sorts of people who staff the technocracy, that this is all a perfectly innocent outgrowth of modern states being more complex and demanding to run. The thinking goes that it was fine to leave the government in the hands of yeoman farmers and urban proles a century ago, when the government didn’t do very much, but today the technical details of governance are beyond any but the most specialized professionals, so we need to leave it all to them.

I think this explanation has something going for it, I admire the structure of its argument, but it also can’t be the whole story. For starters, it treats the scope and nature of the state’s responsibilities as a fixed law of nature. Another way to frame this objection is that you can easily take the story I just told and reverse the causality — the common people used to rule, and so they created a government simple enough for them to understand and command; whereas today unelected legions of technocrats rule, and so they’ve created a government that plays to their strengths. There’s no a priori reason to prefer one of these explanations over the other. There needs to be a higher principle, a superseding reason that results in selecting one compatible ruler-state dyad over another. I think there is such a principle, we just have to get darker and more cynical.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: MITI and the Japanese Miracle by Chalmers Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-04-03.

May 20, 2024

The economic distortions of government subsidies

The Canadian federal and provincial governments are no strangers to the (political) attractions of picking winners and losers in the market by providing subsidies to some favoured companies at the expense not only of their competitors but almost always of the economy as a whole, because the subsidies almost never produce the kind of economic return promised. The current British government has also been seduced by the subsidies game, as Tim Congdon writes:

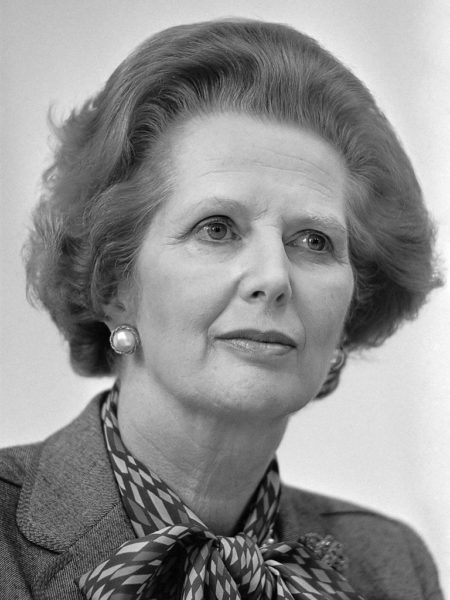

Former British Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1983. She was in office from May 1979 to November 1990.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Why do so many economists support a free market? By the phrase they mean a market, or even an economy dominated by such markets, where the government leaves companies and industries alone, and does not try to interfere by “picking winners” and subsidising them. Two of the economists’ arguments deserve to be highlighted.

The first is about the good use — the productivity — of resources. To earn a decent profit, most companies have to achieve a certain level of output to attract enough customers and to secure high enough revenue per worker.

If the government decides to give money to a favoured group of companies, these companies can survive even if they produce less, and obtain lower revenue per worker, than the others. The subsidisation of a favoured group of companies therefore lowers aggregate productivity relative to a free market situation.

In this column last month I compared the economically successful 1979–97 Conservative government with the economically unsuccessful 2010–2024 Conservative government, which is now coming to an end. In the context it is worth mentioning that Margaret Thatcher and her economic ministers had a strong aversion to government subsidies of any kind.

According to Professor Colin Wren of Newcastle University’s 1996 study, Industrial Subsidies: the UK Experience, subsidies were slashed from £5 billion (in 1980 prices) in 1979 to £0.3 billion in 1990. (In today’s prices that is from £23 billion to under £1.5 billion.)

Thatcher is controversial, and she always will be. All the same, the improvement in manufacturing productivity in the 1980s was faster than before in the post-war period and much higher than it has been since 2010. Further, one of Thatcher’s beliefs was that if the private sector refuses to pursue a supposed commercial opportunity, the public sector most certainly should not try to do so.

Such schemes as HS2 and the Hinkley Point nuclear boondoggle could not have happened in the 1980s or 1990s. They will result in pure social loss into the tens of billions of pounds and will undoubtedly reduce the UK’s productivity.

But there is a second, and also persuasive, general argument against subsidies and government intervention in industry. An attractive feature of a free market policy is its political neutrality. Because market forces are to determine commercial outcomes, businessmen are wasting their time if they lobby ministers and parliamentarians for financial aid.

Honest and straightforward tax-paying companies with British shareholders are rightly furious if they see the government channelling revenues towards other companies who have access to the right politicians and friendly civil servants. By definition, the damage to the UK’s interests is greatest if the recipients of government largesse are foreign.

QotD: “Selfless” public servants

WARNING: If you’re an elected government official or if you’re attached to idealistic notions about such officials, do not read this commentary. It will offend you.

Ideally, government in a democratic republic reflects the will of the people, or at least that of the majority. Citizens vote for candidates whom they believe will best promote the general welfare. Victorious candidates, after pledging to uphold the Constitution, go to state capitals or to Washington, D.C., to do The People’s business — to undertake all the good and worthy activities that citizens in their private capacities cannot perform.

Sure, every now and then crooks and demagogues win office, but these are not the norm. Our system of regular, aboveboard democratic elections ensures that officials who do not effectively carry out The People’s business are thrown from office and replaced by more reliable public servants.

Trouble is, it’s not true. It’s a sham. Despite being called “the Honorable”, the typical politician is certainly no more honorable than the typical dentist, auto mechanic, Wal-Mart regional manager or any other private citizen.

Despite being referred to as “public servants”, politicians serve, first and foremost, their own personal political ambitions and they do so by pandering to narrow special interest groups.

Don Boudreaux, “Base Closings”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-03-18.

May 19, 2024

QotD: Taxation and theft

High-income earners pay a higher rate of tax than people on low incomes. So why is it unfair, as Kim Beazley argues, that high-income earners receive a larger tax cut?

An analogy: your house and your neighbour’s house are both burgled. You lose a television. He loses a DVD player, microwave, his collection of Chomsky memorabilia (it’s an inner-city house), and a unique framed Leunig depicting Mr Curly’s pedophilia arrest. Would it be unfair if police were to return all of this fellow’s belongings, and you were only to get back your 24-inch Sony?

Tim Blair, “Simplistic right-wing greed justification attempted”, Road to Surfdom, 2005-05-12.

[H/T to Samizdata, both for the link and for their title on the post, which I’ve purloined.]

May 17, 2024

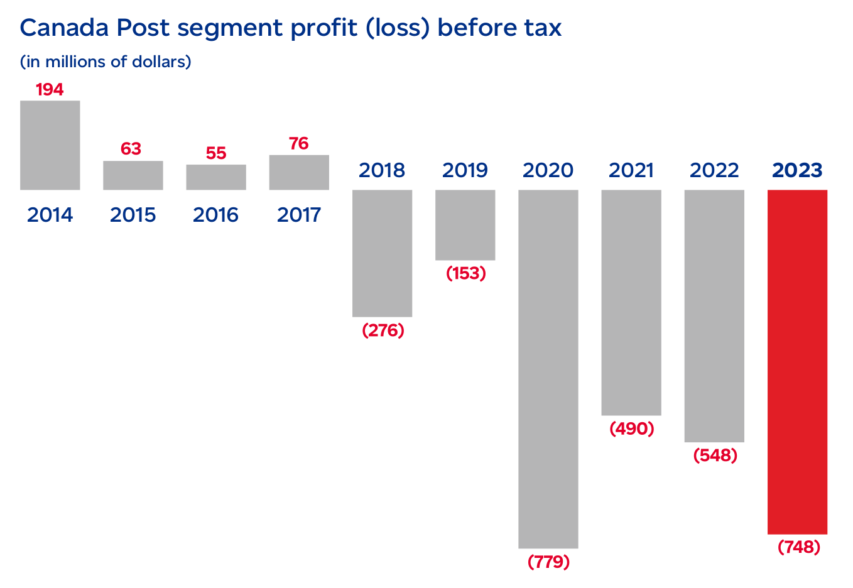

Canada Post is in deep, deep trouble

I was vaguely aware that Canada Post has been in financial difficulties for a while, but I had no idea things were quite this dire:

You’d better believe that the Canada Post Corporation is in very deep trouble. Here’s how they phrased it in their 2023 annual report:

Canada Post’s financial situation is unsustainable.

“Unsustainable”. Well that doesn’t sound good. Think they’re just putting on a show to carve out a better negotiating position? Well, besides for the fact that they’re not currently negotiating with anyone, the numbers do bear out the concern:

For 2023, the Corporation recorded a loss before tax of $748 million, compared to a loss before tax of $548 million in 2022. From 2018 to 2023, Canada Post lost $3 billion before taxes. Without changes and new operating parameters to address our challenges, we forecast larger and increasingly unsustainable losses in future years.

In other words, it’s madly-off-in-all-directions panic time.

Hey! You know I can hear your condescending sniff: “I’m sure this is just a temporary disruption. They’ll figure out how to fix the leak and get themselves back on the road like always. They’re too big to fail.”

Yeah … not this time. The competition from digital communications (i.e., the internet), FedEx, and UPS isn’t going anywhere. Letter delivery nosedived from nearly 5.5 billion pieces in 2006 to just 2.2 billion in 2022. And vague references to “major strategic changes to transform our information technology model” don’t sound much like magic bullets for reversing the decline.

But Canada Post’s labour and pension costs sure are marching bravely forward. In fact, if it wasn’t for Parliamentary relief in the form of Canada Post Corporation Pension Plan Funding Regulations, the Corporation would have had to pay $354 million into the pension plan in 2023 alone. But that $354 million — plus whatever additional amounts show up in 2024 and besides the $998 million in existing general debt — are still liabilities that’ll eventually need paying.

May 16, 2024

The replication crisis and the steady decline in social trust

Theodore Dalrymple on the depressing unreliability — and sometimes outright fraudulence — of far too high a proportion of what gets published in scientific journals:

Until quite recently — I cannot put an exact date on it — I assumed that everything published in scientific journals was, if not true, at least not deliberately untrue. Scientists might make mistakes, but they did not cheat, plagiarise, falsify, or make up their results. For many years as I opened a medical journal, the possibility simply that it contained fraud did not occur to me. Cases such as those of the Piltdown Man, a hoax in which bone fragments found in the Piltdown gravel pit were claimed to be those of the missing link between ape and man, were famous because they were dramatic but above all because they were rare, or assumed to be such.

Such naivety is no longer possible: instances of dishonesty have become much more frequent, or at least much more publicised. Whether the real incidence of scientific fraud has increased is difficult to say. There is probably no way to estimate the incidence of such fraud in the past by which a proper comparison can be made.

There are, of course, good reasons why scientific fraud should have increased. The number of practising scientists has exploded; they are in fierce competition with one another; their careers depend to a large extent on their productivity as measured by publication. The difference between what is ethical and unethical has blurred. They cite themselves, they recycle their work, they pay for publication, they attach their names to pieces of work they have played no part in performing and whose reports they have not even read, and so forth. As new algorithms are developed to measure their performance, they find new ways to play the game or to deceive. And all this is not even counting commercial pressures.

Furthermore, the general level of trust in society has declined. Are our politicians worse than they used to be, as it seems to everyone above a certain age, or is it that we simply know more about them because the channels of communication are so much wider? At any rate, trust in authority of most kinds has declined. Where once we were inclined to say, “It must be true because I read it in a newspaper”, we are now inclined to say, “It must be untrue because I read it in a newspaper”.

Quite often now I look at a blog called Retraction Watch which, since 2010, has been devoted to tracing and encouraging retraction of flawed scientific papers, often flawed for discreditable reasons. Such reasons are various and include research performed on subjects who have not given proper consent. This is not the same as saying that the results of such research are false, however, and raises the question of whether it is ethical to cite results that have been obtained unethically. Whether it is or not, we have all benefited enormously from past research that would now be considered unethical.

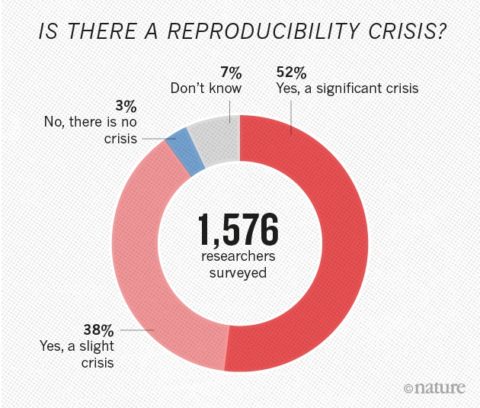

One common problem with research is its reproducibility, or lack of it. This is particularly severe in the case of psychology, but it is common in medicine too.

The Canadian Senate is an anti-democratic fossil … that might totally frustrate a future Conservative government

Tristin Hopper considers the constitutional weirdness of Canada’s upper house, an appointed body that has the power to block a popularly elected House of Commons:

“In the east wing of the Centre Block is the Senate chamber, in which are the thrones for the [King and Queen], or for the federal viceroy and his or her consort, and from which either the sovereign or the governor general gives the Speech from the Throne and grants Royal Assent to bills passed by parliament. The senators themselves sit in the chamber, arranged so that those belonging to the governing party are to the right of the Speaker of the Senate and the opposition to the speaker’s left. The overall colour in the Senate chamber is red, seen in the upholstery, carpeting, and draperies, and reflecting the colour scheme of the House of Lords in the United Kingdom; red was a more royal colour, associated with the Crown and hereditary peers. Capping the room is a gilt ceiling with deep octagonal coffers, each filled with heraldic symbols, including maple leafs, fleur-de-lis, lions rampant, clàrsach, Welsh Dragons, and lions passant. On the east and west walls of the chamber are eight murals depicting scenes from the First World War; painted in between 1916 and 1920”

Photo and description by Saffron Blaze via Wikimedia Commons.

By the anticipated date of the 2025 federal election, only 10 to 15 members of the 105-seat Senate will be either Conservative or Conservative appointees. The rest will be Liberal appointees. As of this writing, 70 senators have been personally appointed by Trudeau, and he’ll likely have the opportunity to appoint another 12 before his term ends.

What this means is that no matter how strong the mandate of any future Conservative government, the Tory caucus will face a Liberal supermajority in the Senate with the power to gut or block any legislation sent their way.

“If a majority of the Senate chose to block or severely delay a Conservative government’s legislative agenda, it would plunge the country into a constitutional crisis the likes of which we have not seen in more than a century,” reads an analysis published Tuesday in The Hub.

Constitutional scholars Howard Anglin and Ray Pennings envisioned a potential nightmare scenario in which the Senate casts themselves as “resisting” a Conservative government. Given that senators are all permanently appointed until their mandatory retirement at age 75, it would take at least 10 years until a Conservative government could rack up enough Senate appointments to overcome the Liberal-appointed majority.

“Canadian politics would grind to the kind of impasse that is only broken by the kind of extraordinary force whose political and social repercussions are unpredictable,” they wrote.

The piece even makes a passing reference to 1849, when mobs burned down Canada’s pre-Confederation parliament.

The prospect of an all-powerful Senate able to block the mandate of an elected government is a legislative situation almost entirely unique to Canada.

New Zealand abolished its Senate and is now governed by a unicameral legislature. Australia and the United States both employ term-limited elected senates. The U.K. House of Lords – on which the Canadian Senate is closely modelled – is severely constrained in how far it can check the actions of the House of Commons.

But in Canada, the Senate essentially retains the power of a second House of Commons; it can do whatever it wants to legislation that has passed the House of Commons, including spike it entirely.