Michael Pacitti

Published Dec 24, 2022Differentiating between Art Deco and Streamline Moderne can be difficult if you don’t know their history. They are two very different periods of design. Here is a look at those differences, characteristics, colors, transportation, influences, and more.

May 3, 2024

Art Deco vs Streamline Moderne

May 2, 2024

Rome’s Biggest Construction Projects

toldinstone

Published Jan 26, 2024Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

3:06 Domitian’s Temple of Jupiter

4:45 Aura

5:48 The Forum of Trajan

7:16 Nero’s Golden HouseMy new book, Insane Emperors, Sunken Cities, and Earthquake Machines is now available! Check it out here: https://www.amazon.com/Insane-Emperor…

April 13, 2024

QotD: Architects and modern architecture

Eventually, the deeply impoverished language of Bauhaus or Corbusian architecture became evident even to architects, possibly the most obtuse professional group in the world (though educationists are not far behind). But their turning away from the dreariness of what Professor Curl calls Corbusianity has hardly improved matters. They discovered the delights — for themselves — of originality without the discipline of even a reduced vernacular, of giving buildings outlandish shape simply because it was possible to do so, the more outlandish the more attention being drawn to themselves. Thus the skyline of the City of London has been adorned with Brobdingnagian dildoes and early mobile telephones, turning the city into a damp, overcrowded cut-price Dubai; and Paris — the City of Light — has been the dubious distinction of having built three of the worst buildings in the world, the Centre Pompidou, the Musée du Quai Branly and the Philaharmonie, the latter two by the architect who dresses like a fascist thug, Jean Nouvel. I cannot pass these buildings without thinking au bagne!; and indeed, I have a French book whose title, Faut-il pendre les architectes?, asks whether it is necessary to hang the architects.

Professor Curl’s is a very painful book to read. In one sense his targets are easy for, as the photos amply demonstrate, modernist architecture and its successors are so awful that it scarcely requires any powers of judgment to perceive it. It is like seeing a TV evangelist and knowing at once that he is a crook. Yet modernist architecture, despite its patent hideousness and inhumanity, still has its defenders, especially in the purlieus of architectural schools. Moreover, the population has been browbeaten into believing that there was never any alternative, and it is obvious that to undo the damage would take decades, untold determination and vast expenditure. Removing the Tour Montparnasse alone would probably cost several billion. No one is prepared to make this colossal effort.

What Walter Godfrey wrote in 1954 is debatable:

It is not an exaggeration to say that nine men out of ten have lost all sensitiveness to an art that was once a matter of common interest.

If this is true, it is because they have learned to accept, or swallow what they are given. The epidemiology of graffiti, however, suggests to me that, at least subliminally, men still take notice of their surrounding and are affected by them: defacement is overwhelmingly of hideous Corbusian surfaces, that is to say on what Corbusier called “my friendly concrete”.

As for the architects and their acolytes, the architectural commentators, they hide behind the claim that most people do not “understand”. They claim that modernist architecture is better than it looks or functions, that it is “honest”, a weaselly word in this context. The architects cannot recognise the obvious for the same reason that Macbeth could not stop murdering once he had started:

I am in blood

Stepped in so far that should I wade no more

Returning were as tedious as to go o’reProfessor Curl has written an essential, uncompromising, learned, sometimes slightly densely, critique of one of the worst and most significant legacies of the 20th century. He offers a slight glimmer of hope in the existence of architects who, bravely, have resisted the blandishments of celebrity status and the approbation of their corrupted peers. His book has a wonderful bibliography, the fruit of a lifetime of reading and reflection, that will give me occupation for a long time to come. It is a loud and salutary clarion call to resist further architectural fascism.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

March 19, 2024

Buildings Can Make You A Better Builder

Lost Art Press

Published Nov 26, 2023

Read and subscribe to the Lost Art Press Blog: https://blog.lostartpress.com/

January 11, 2024

Art Deco Architecture

Prof. Lynne Porter

Published 22 Apr 2021Lecture for Fairfield University class called “What We Leave Behind: the History of Fashion & Decor”.

January 3, 2024

Highlights of Diocletian’s Palace in Split

Scenic Routes to the Past

Published 6 Oct 2023A Roman historian’s tour of the Palace of Diocletian in Split, Croatia.

Chapters

0:00 Diocletian and his palace

0:59 Overview and layout

2:37 South facade

3:07 East facade

3:39 Porta Aurea

4:09 Peristyle

4:48 Temple of Jupiter

5:49 Reception rooms (vestibule and substructures)

6:23 Mausoleum of Diocletian / Cathedral

December 15, 2023

The Pagan Necropolis Under Vatican City

toldinstone

Published 1 Sept 2023Beneath the floor of St. Peter’s Basilica, an ancient Roman cemetery holds the secret to the origins of Vatican City.

(more…)

December 11, 2023

This man built his office inside a lift

Tom Scott

Published 28 Aug 2023The Baťa Skyscraper, in Zlín, Czechia, is a landmark of architecture. And the office of Jan Antonín Baťa … is an elevator.

Thanks to the museum staff for fact-checking and translation!

(more…)

QotD: The Palace of Westminster

Work outwards from this change and you will begin to have some idea of how much Britain has altered. The bits you don’t or can’t see are as unsettlingly different as those tattoos. Look up instead at the Houses of Parliament, all pinnacles, leaded windows, Gothic courtyards and cloisters, which look to the uninitiated as if they are a medieval survival. In fact they were completed in 1860, and are newer than the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The only genuinely ancient part — not used for any governing purpose — is the astonishing chilly space of Westminster Hall, faintly redolent of the horrible show trial of King Charles I, still an awkward moment in the national family album. But those who chose the faintly unhinged design wanted to make a point about the sort of country Britain then was, and they were very successful. Gothic meant monarchy, Christianity, and conservatism. Classical meant republican, pagan, and revolutionary, and mid-Victorian Britain was thoroughly wary of such things, so Gothic was chosen and the Roman Catholic genius Augustus Welby Pugin let loose upon the design. Wherever you are in the building, it is hard to escape the feeling of being either in a church, or in a country house just next to a church. The very chimes of the bell tower were based upon part of Handel’s great air from The Messiah: “I know that my Redeemer liveth”.

I worked for some years in this odd place. It is by law a Royal Palace, so nobody was ever officially allowed to die on the premises, in case the death had to be inquired into by some fearsome, forgotten tribunal, perhaps a branch of Star Chamber. Those who appeared to have deceased were deemed to be still alive and hurried to a nearby hospital where life could be pronounced extinct and an ordinary inquest held. We were also exempt from the alcohol laws that used in those days to keep most bars shut for a lot of the time, and if the drinks were not free they were certainly amazingly cheap.

In my years of wandering its corridors and lobbies, of hanging about for late-night votes and dozing in committee rooms, I came to loathe British politics and to mistrust the special regiment of journalists (far too close to their sources) who write about it. I had hoped for a kingdom of the mind and found a squalid pantry in which greasy, unprincipled deals were made by people who were no better than they ought to be.

But I came to love the building. Once you had got past the police sentinels, who knew who everyone was, you could go everywhere, even the thrilling ministerial corridor behind the Speaker’s chair, from which Prime Ministers emerged to face what was then the genuine ordeal of Parliamentary questions, twice a week. There was a rifle range beneath the House of Lords, set up during World War I to make sure honorable members of both Houses would be able to shoot Germans accurately if they ever met any. There was a room where they did nothing but prepare vast quantities of cut flowers, and which perfumed the flagstone corridor in which it lay. There was a convivial staff bar (known to few) where the beer was the best in the building and politicians in trouble would hide from their colleagues. The Lords had a whole half of the Palace, with lovely murals illustrating noble moments of our history, and the Chief Whip’s cosy, panelled office where reporters would be summoned once a week for dangerous gossip and perilously large glasses of whisky or very dry sherry, generously refilled. And high up in the roof, looking down over the murky Thames, was the room where the government briefed us, in meetings whose existence we were sworn never to reveal. Now they are pretty much public, so the real briefings must happen somewhere else, I suppose.

Peter Hitchens, “An Empty Parliament”, First Things, 2017-10-03.

December 8, 2023

The development of the American suburb

In the latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, Jane Psmith discusses A Field Guide to American Houses (Revised): The Definitive Guide to Identifying and Understanding America’s Domestic Architecture, by Virginia Savage McAlester. In particular, she looks at McAlester’s coverage of how suburbs developed:

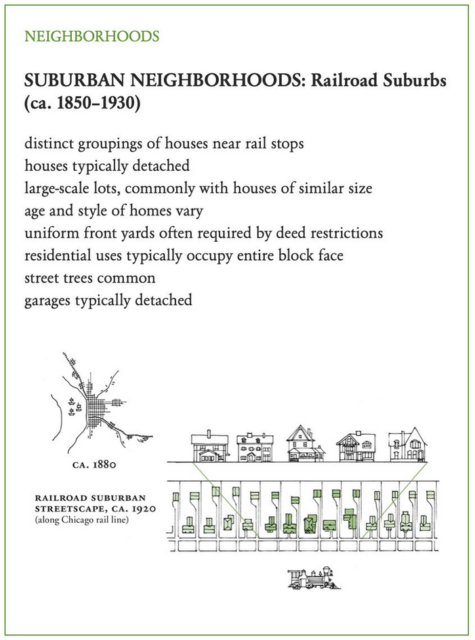

After some brief but interesting discussion of cities,1 most of the page count is devoted to the suburbs. It’s a sensible choice: suburbs have by far the most varied types of house groupings, and more than half of Americans live in one. But what exactly is a “suburb”? It’s a wildly imprecise word, referring to anything that is neither truly rural nor the central urban core, and suburbs vary tremendously in character. As a working definition, though, a suburb is marked by free-standing houses on relatively larger lots. (If you can think of a counter-example that qualifies but is “urban”, I’ll bet you $5 it started out as a suburb before the city ate it.)

This means that building a suburb has a few obvious technological prerequisites, which McAlester lists as follows: First, balloon-frame construction, which enabled not just corners but quick and inexpensive construction generally and removed much of the incentive for the shared walls that were so common in the early cityscape. Second, the proliferation of gas and electric utilities in the late nineteenth century meant that the less energy-efficient free-standing homes could still be heated relatively inexpensively. Third, the spread of telephone service after 1880 meant that it was much easier to stay in touch with friends whose front doors weren’t literally ten feet away from yours.2 But by far the most important technological advances came in the field of transportation, which is obviously necessary if you’re going to live in the country (or a reasonable facsimile thereof) and work in the city.

The first of these transportation advances was the railroad. In fact “railroad suburb” is a bit of a misnomer, because most of the collections of houses that grew up around the new rail stops were fully functional towns that had their own agricultural or manufacturing industries. The most famous railroad suburbs, however, were indeed planned as residential communities serving those wealthy enough to pay the steep daily rail fare into the city. Llewellyn Park near New York City, Riverside near Chicago, and the Main Line near Philadelphia are all examples of railroad suburbs that have maintained their tony atmosphere and high property values.

The next and more dramatic change was the advent of the electric trolley or streetcar, first introduced in 1887 but popular until about 1930. (That’s what all the books say, but come on, it’s probably October 1929, right?) Unlike steam locomotives, which take quite a long time to build up speed or to slow down again, and so usually had their stations placed at least a mile apart, streetcars could start and stop far more easily and feature many more, and more densely-placed, stops. Developers typically built a streetcar line from the city veering off into the thinly-inhabited countryside, ending at an attraction like a park or fairground if possible. If they were smart, they’d bought up the land along the streetcar beforehand and could sell it off for houses,3 but either way the new streetcar line added value to the land and the development of the land made the streetcar more valuable.

You can easily spot railroad towns and streetcar suburbs in any real estate app if you filter by the date of construction (for railroad suburbs try before 1910, for streetcar before 1930) and know what shapes to look for. Railroad towns are typically farther out from the urban center and are built in clusters around their stations, which are a few miles from one another. Streetcar suburbs, by contrast, tend to be continuous but narrow, because the appeal of the location dropped off rapidly with distance from the streetcar line. (Lots are narrow for the same reason — to shorten the pedestrian commute.) They expand from the urban center like the spokes of a wheel.

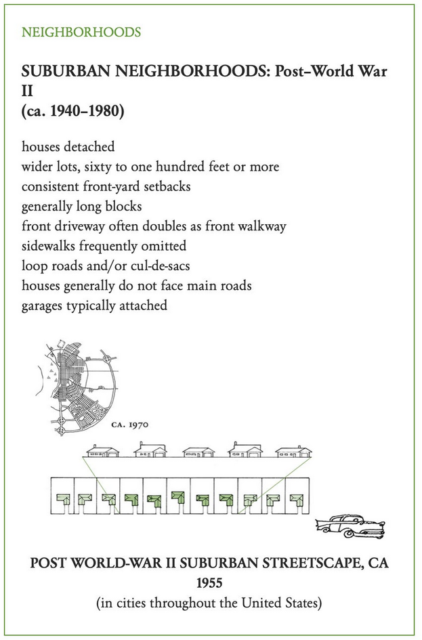

And then came the automobile and, later, the federal government. The car brought a number of changes — paved streets, longer blocks, wider lots (you weren’t walking home, after all, so it was all right if you had to go a little farther) — but nothing like the way the Federal Housing Authority restructured neighborhoods.

The FHA was created by the National Housing Act of 1934 with the broad mandate to “improve nationwide housing standard, provide employment and stimulate industry, improve conditions with respect to mortgage financing, and realize a greater degree of stability in residential construction”. It was a big job, and the FHA set out to accomplish it in a typical New Deal fashion: providing federal insurance for private construction and mortgage loans, but only for houses and neighborhoods that met its approval. This has entered general consciousness as “redlining”, after the color of the lines drawn around uninsurable areas (typically old, urban housing stock),4 but the green, blue, and yellow lines — in order of declining insurability — were just as influential on the fabric of contemporary America.

A slow economy through the 1930s and a prohibition on nonessential construction during the war meant that FHA didn’t have much to do until 1945, but as soon as the GIs began to come home and take advantage of their new mortgage subsidies, there was a massive construction boom. With the FHA insuring both the builders’ construction loans and the homeowners’ mortgages, nearly all the new neighborhoods were built to the FHA’s exacting specifications.

One of the FHA’s major concern was avoiding direct through-traffic in neighborhoods. Many post-World War II developments were built out near the new federally-subsidized highways on the outskirts of the cities, so the FHA was eager to protect new subdivisions from heavy traffic on the interstates and the major arterial roads. Neighborhoods were meant to be near the arterials, but with only a few entrances to the neighborhood and many curved roads and culs-de-sac within it. Unlike the streetcar suburbs or the early automobile suburbs that filled in between the “spokes” of the streetcar lines, where retail had clustered near the streetcar stops, the residents of the post-World War II suburbs found their closest retail establishments outside the neighborhood on the major arterial roads. Lots became wider, blocks longer, and sidewalks less frequent; houses were encouraged to stay small by FHA caps on the size of loans. And although we tend to assume they were purely residential areas, the FHA encouraged the inclusion of schools, churches, parks, libraries, and community centers within the neighborhood.

1. America doesn’t have many urban neighborhoods that predate 1750, and even fewer that persist in their original layout, but if you’ve ever visited one it’s amazing how compact everything feels even in comparison to the rowhouses of the following century.

2. McAlester’s footnote for the paragraph that contains all this reads: “These three essentials were highlighted in an essay the author has read but has not been successful in locating for this footnote.”

3. This is still, I am told, how some of the more sensibly-governed parts of the world run their transit systems: whatever company has the right to build subways buys up the land around a planned (but not announced) subway line through shell corporations, builds the subway, then sells or develops the newly-valuable property. Far more efficient as a funding mechanism than fares!

4. This 2020 NBER working paper points out that redlined areas were 85% white (though they did include many of the black people living in Northern cities) and suggests that race played very little role in where the red lines were drawn; rather, black people were already living in the worst neighborhoods.

November 25, 2023

Crystal Palace Station is Needlessly Magnificent

Jago Hazzard

Published 9 Aug 2023Crystal Palace and the station built for it. Well, one of them.

(more…)

November 2, 2023

Keeping Clean in Rome

seangabb

Published 2 Jul 2023A lecture, given in June 2023, about bathing and keeping clean in the Roman World — plus an overview of depilation and going to the toilet.

(more…)

October 29, 2023

Architect Breaks Down 5 of the Most Common New York Apartments | Architectural Digest

Architectural Digest

Published 14 Jun 2022Michael Wyetzner of Michielli + Wyetzner Architects returns to AD, this time breaking down five of the most common apartment types found in New York City. From long and narrow railroad-style abodes to stately multi-level brownstones and everything in between, Michael gives expert insight on the many different places you can call home in the big apple.

(more…)

October 15, 2023

History Summarized: The Castles of Wales

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 23 Jun 2023Every castle tells a story, but when one small country has over 600 castles, the collective story they tell is something like “holy heck ouch, ow, oh god, why are there so many arrows, ouch, good lord ow” – And that’s Wales for you.

(more…)

October 11, 2023

Art Deco in 9 Minutes: Why Is It The Most Popular Architectural Style?

Curious Muse

Published 3 Sept 2021What comes to your mind when you think of the 1920s? For most people, the 1920s conjures up images of jazz, flappers, Old Hollywood, the Great Gatsby, and the Chrysler Building in New York City. It was a time of prosperity, exorbitant spending, and entertainment that gave rise to one of the most popular decorative arts and architecture movements — known as Art Deco.

Characterized by exquisite craftsmanship, lavish decoration, and rich materials, the style has become synonymous with the Roaring Twenties. So, what was the Art Deco movement all about and what differentiates it from other major movements? Finally, despite its popularity today, what makes Art Deco so closely associated with the 1920s?

In this week’s video, we’ll dive into the history of the era and learn about Art Déco, the style that continues to inspire designers and architects around the world!

(more…)