Essentially the problem that miners faced was that while mining could be a complex and technical job, the vast majority of the labor involved was largely unskilled manual labor in difficult conditions. Since the technical aspects could be handled by overseers, this left the miners in a situation where their working conditions depended very heavily on the degree to which their labor was scarce.

In the ancient Mediterranean, the clear testimony of the sources is that mining was a low-status occupation, one for enslaved people, criminals and the truly desperate. Being “sent to the mines” is presented, alongside being sent to work in the mills, as a standard terrible punishment for enslaved people who didn’t obey their owners and it is fairly clear in many cases that being sent to the mines was effectively a delayed death sentence. Diodorus Siculus describes mining labor in the gold mines of Egypt this way, in a passage that is fairly representative of the ancient sources on mining labor more generally (3.13.3, trans Oldfather (1935)):

For no leniency or respite of any kind is given to any man who is sick, or maimed, or aged, or in the case of a woman for her weakness, but all without exception are compelled by blows to persevere in their labours, until through ill-treatment they die in the midst of their tortures. Consequently the poor unfortunates believe, because their punishment is so excessively severe, that the future will always be more terrible than the present and therefore look forward to death as more to be desired than life.

It is clear that conditions in Greek and Roman mines were not much better. Examples of chains and fetters – and sometimes human remains still so chained – occur in numerous Greek and Roman mines. Unfortunately our sources are mostly concerned with precious metal mines and those mines also seem to have been the worst sorts of mines to work in, since the long underground shafts and galleries exposed the miners to greater dangers from bad air to mine-collapses. That said, it is hard to imagine working an open-pit iron mine by hand, while perhaps somewhat safer, was any less back-breaking, miserable toil, even if it might have been marginally safer.

Conditions were not always so bad though, particularly for free miners (being paid a wage) who tended to be treated better, especially where their labor was sorely needed. For instance, a set of rules for the Roman mines at Vipasca, Spain provided for contractors to supply various amenities, including public baths maintained year-round. The labor force at Vipasca was clearly free and these amenities seem to have been a concession to the need to make the life of the workers livable in order to get a sufficient number of them in a relatively sparsely populated part of Spain.

The conditions for miners in medieval Europe seems to have been somewhat better. We see mining communities often setting up their own institutions and occasionally even having their own guilds (for instance, there was a coal-workers guild in Liege in the 13th century) or internal regulations. These mining communities, which in large mining operations might become small towns in their own right, seem to have often had some degree of legal privileges when compared to the general rural population (though it should be noted that, as the mines were typically owned by the local lord or state, exemption from taxes was essentially illusory as the lord or king’s cut of the mine’s profits was the taxes). It does seem notable that while conditions in medieval mines were never quite so bad as those in the ancient world, the rapid expansion of mining activity beginning in the 15th century seems to have coincided with a loss of the special status and privileges of earlier medieval European miners and the status associated with the labor declined back down to effectively the bottom of the social spectrum.

(That said, it seems necessary to note that precious metal-mining done by non-free Native American laborers at the order of European colonial states appears to have been every bit as cruel and deadly as mining in the ancient world.)

Bret Devereaux, “Iron, How Did They Make It? Part I, Mining”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-09-18.

June 24, 2023

QotD: The plight of miners in pre-industrial societies

June 23, 2023

The Combat Engineers of D-Day – WW2 Special Documentary

World War Two

Published 22 Jun 2023How do you blast through the obstacles and minefields on the beaches of Normandy? How do you get thousands of tonnes of tanks, guns, and men into the fight? And what about reopening the shattered French ports? You need men who are as skilled in construction as they are destruction. You need the engineers.

(more…)

FG-42: Perhaps the Most Impressive WW2 Shoulder Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Mar 2023The first production version of the FG42 used a fantastically complex milled receiver and a distinctive sharply swept-back pistol grip. A contract to make 5,000 of them was awarded to Krieghoff in late spring of 1943, but by the fall its replacement was already well into development. The milled receiver used a lot of high-nickel steel which was becoming difficult for Germany to acquire, and it was decided to develop a stamped receiver to ease production obstacles. Ultimately only about 2,000 of the early Type E FG42 rifles were actually made, and only 12 or 15 are registered in the US. They are a remarkably advanced rifle, and extremely interesting.

(more…)

QotD: Children and fire

UCLA anthropologist Dan Fessler argues that during middle childhood (ages 6-9) humans go through a phase in which we are strongly attracted to learning about fire, by both observing others and manipulating it ourselves. In small-scale societies, where children are free to engage this curiosity, adolescents have both mastered fire and lost any further attraction to it. Interestingly, Fessler also argues that modern societies are unusual because so many children never get to satisfy their curiosity, so their fascination with fire stretches into the teen years and early adulthood.

Joseph Henrich, The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter, 2015.

June 22, 2023

Britain’s 17th century repeats: first time as tragedy, the second time as farce?

Dominic Sandbrook on the parallels between Britain in the 1600s and today:

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

A sunny Wednesday in early June 1665, and Samuel Pepys was suffering in the heat. It was “the hottest day that ever I felt in my life”, he confided to his diary, “and it is confessed so by all other people the hottest they ever knew in England”.

Pepys spent some of the day strolling with friends in the New Exchange, a shopping arcade on the south side of the Strand, before repairing to Vauxhall’s Spring Gardens, where he “walked an hour or two with great pleasure”. There was something on his mind, though. For as long as he could remember, relations with England’s neighbours had been distinctly fraught, and Lord Sandwich’s fleet was currently engaged in a struggle with the Dutch. London simmered with rumours about the outcome of the battle, but there was no certainty: as Pepys put it, “ill reports run up and down of his being killed, but without ground”.

By evening, “weary with walking and with the mighty heat of the weather”, the diarist had returned to his house in the City. The day had been pleasant enough, but now something else was troubling him. In Drury Lane, he had seen “two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “‘Lord have mercy upon us’ writ there”. Pepys knew immediately what that meant. Plague — the first sign of the epidemic that would kill an estimated 100,000 people, a quarter of the capital’s population, in the next 18 months. To calm his nerves, he noted: “I was forced to buy some roll-tobacco to smell to and [chew], which took away the apprehension.”

Reading Pepys’s diary, you sometimes forget that he was born almost four centuries ago. In many respects he was utterly different from us, with assumptions and anxieties we can scarcely understand; and yet often he feels almost thrillingly contemporary, as if you might bump into him in the street tomorrow afternoon. Indeed, you merely have to re-read that diary entry, and you might be looking in a mirror: the stifling heat, the fears of disease, the foreign wars, the fake news.

The past is never just a mirror, of course, and it’s the height of narcissism to cast our predecessors as mere foreshadowings of ourselves. But there are times when, for obvious reasons, a particular historical moment catches the imagination — as is the case today with Pepys’s moment, the mid-17th century.

Just look, for example, at the titles in Britain’s bookshops. For a long time, commercial publishers were terrified of the 17th century. The Stuarts weren’t as sexy as the Tudors, and the age of Oliver Cromwell seemed too dark, too violent, too religious, too complicated for ordinary readers. Why read about perhaps the most significant moment in all our history — the titanic revolutionary conflict of the 1640s and 1650s, when armies surged across the map of our islands, a king was tried and executed, and a farmer from East Anglia tried to turn Britain into a religious commonwealth — when you could read yet another book about Catherine Howard?

And then, as if responding to some subterranean shift in the cultural landscape, something changed. The last few years alone have given us excellent books on Cromwell by Paul Lay and Ronald Hutton, as well as Anna Keay’s dazzling social history of Britain in the 1650s, and Malcolm Gaskill’s haunting account of witchcraft among the settlers who tried to build a new England on the other side of the Atlantic. Meanwhile, Robert Harris’s most recent blockbuster, Act of Oblivion, follows the hunt for Charles I’s Parliamentarian killers from England to America.

Even politicians are at it. In the Conservative MP Jesse Norman’s new novel The Winding Stair, which charts the bitter feud between Sir Francis Bacon, father of the Scientific Revolution, and Sir Edward Coke, the most influential jurist of the early modern era, we appear to be plunged back into the world of early 17th-century Jacobean England. But right from the first few pages, the parallels are obvious. Among his characters, for example, is James I, a man with “bulging, expressive eyes” and an “awkward gait”, who “dresses finely, yet somehow manages to look ill-kempt”, and always “loves to display his learning with a classical or biblical line”. Even if you didn’t know that Norman had been at Eton with Boris Johnson, worked for him as a junior minister and eventually released a blistering public letter calling for his removal, you’d probably spot the parallel.

CDR Salamander’s proposal to “encourage” NATO countries to meet or exceed their agreed defence targets

Canada has been a notorious defence freeloader since the first Trudeau government took office in 1968. Every Canadian government since then — until the current government started telling our allies we had no intention of meeting our treaty commitments — has made more-or-less sincere noises about getting back to the 2% of GDP minimum defence budget and none have done much to make it happen (we’re around 1.39% at the moment). Several years ago, CDR Salamander proposed a new way to allocate NATO leadership roles according to how close to the minimum each member country has managed to get, and it’s surprising that something of the sort hasn’t already been implemented:

Canada has been a notorious defence freeloader since the first Trudeau government took office in 1968. Every Canadian government since then — until the current government started telling our allies we had no intention of meeting our treaty commitments — has made more-or-less sincere noises about getting back to the 2% of GDP minimum defence budget and none have done much to make it happen (we’re around 1.39% at the moment). Several years ago, CDR Salamander proposed a new way to allocate NATO leadership roles according to how close to the minimum each member country has managed to get, and it’s surprising that something of the sort hasn’t already been implemented:

It should bring to the front that NATO can no longer allow unserious nations to play like they are anything but security free-riders. They need to contribute their fair share or pay some consequence. Alliances have benefits and responsibilities. You should not have one without the other.

While percentage of GDP is an imperfect measure of contribution, it is better than all the other ones. It is as simple benchmark of national effort.

As these are the best numbers we have, let’s look at 2021 and then forward.

It is amazing that after all Russia has shown Western Europe — both of its nature and the nature of modern warfare — that so many of our NATO allies continue to slow walk defense spending, doing the very minimum to be a full and fair partner in the alliance.

Russian victory — however they define it — or Russian defeat — however Ukraine defines it – will not change the geography or nature of Russia. She is not going anywhere.

[…]

There is so much deferred spending from our free-riding European allies.

Between 1999 and 2021, EU combined defence spending increased by 20%, according to reports by the European Defence Agency. That compares with a 66% increase by the US, and 292% by Russia and 592% by China, over the same period.

“Out years” are where dragons live, so anyone not on guide-slope to 2%+ by the end of 2023 — when one way or another the Russo-Ukrainian War should be over — will find someway to not get there in a wave of excuses and bluffing.

We should call their bluff.

As such, and this is generous, we need to finally pursue PLAN SALAMANDER for NATO “Flags-to-Post” that I first proposed almost six years ago.

In NATO, General and Flag Officer billets are distributed amongst nations in a rather complicated way, but this formula is controlled by NATO – and as such – can be changed.

Entering argument: take the present formula for “fair distribution” and multiply by .75 any nation that spends 1.5% to 1.99% GDP on defense. Multiply by .5 any nation that spends between 1.25% to 1.499%. Multiply by .25 1.0% to 1.240%. If you fall below 1%, you get nothing and your OF5 (Col./Capt) billets are halved.

1.25x for 2.01%-2.25%. 1.5X for 2.26%-2.75%; 1.75x for 2.76% -3.0%. 2x for +3.01%.

The math gets funky when a lot of people get over 2%, but we can refine it later. Doesn’t cost a penny and will unquestionably get the attention of those nations. Trust me on this. By January 1st, 2024 no more excuses. A small and symbolic punishment, but a good start that may be all that is needed. This is not the second half of the 20th Century any more.

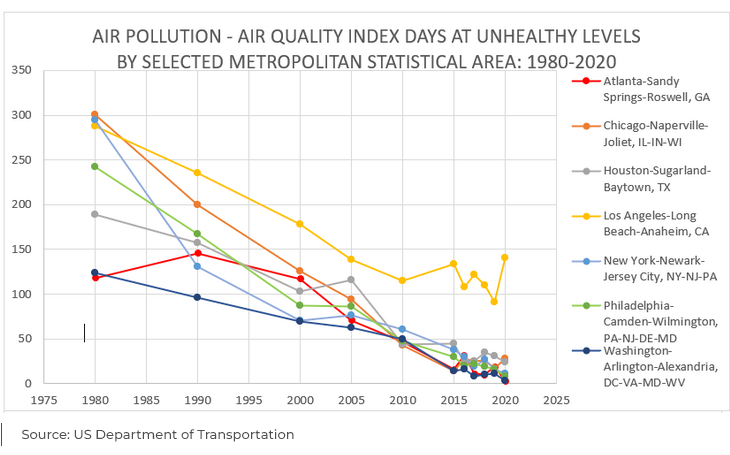

Any news about weather or climate is bad news

The transition of weather from merely reporting on weather conditions and relaying (somewhat) authoritative forecasts is pretty much complete, as now every change in the weather pretty much has to be linked to the dreaded anthropogenic climate change. New York City’s recent poor air quality due to Canadian wildfires highlights a change they haven’t been pushing — how much better air quality in major cities has become:

Earlier this month, as wildfires ravaged Canada, the Northeastern United States experienced heavy air pollution problems from the smoke.

The out of control fires and subsequent pollution is a tragedy, certainly. But the fact that a low-visibility New York City was national news highlights how much things have changed.

Pollution has dramatically declined over the past few decades. To get a clear picture of how much, look at this graph.

This shows the number of days air quality is considered to be at “unhealthy levels” by the US government in seven major metros in the U.S.

All seven metros have improved their air quality since 1980. This is good news!

In the NYC metro, nearly 300 days in 1980 had unhealthy air quality. Today it’s less than 50.

So what’s going on here? Well, some might argue regulation is the primary source. It’s certainly possible that environmental regulations in the end of the 20th century resulted in less pollution. As our technology has improved, we’ve gained the ability to police people polluting the air of their neighbors. But this isn’t the full story.

How & When to Hammer Tap a Plane | Paul Sellers

Paul Sellers

Published 10 Mar 2023We tend to think that modern makers of metal and wooden planes have given us planes that are better adjusted with fine adjusters and therefore dismiss hammer-tapping for setting the plane.

In reality, hammer tapping is non-detrimental and, at the same time, simplifies the setting on many planes.

I use this even on planes that have adjusters. Just because hammer tapping is so effective and immediate. Watch me and you will see what I mean.

——————–

(more…)

QotD: Nuclear non-proliferation and the Russo-Ukraine war

The failure of the earlier League of Nations was crucial to preparing the way for the Second World War. Today, we see none of this, with most participants — excepting North Korea and Iran — still playing by the rules. This is where we return to Nevil Shute. Twice, using his technical expertise, Shute attempted to predict future war in a novel, and twice he got it wrong. With On the Beach, the author wrote of a 37-day war that “had flared all around the northern hemisphere”. Albania had dropped a “cobalt bomb” on Naples, which escalated into wider conflicts and eventually a Russo-Chinese exchange.

As one of Shute’s characters, a scientist, explained, “The trouble is, the damn things got too cheap. The original uranium bomb cost about fifty thousand quid towards the end. Every little pipsqueak country like Albania had a stockpile of them, and every little country that had that, thought it could defeat the major countries in a surprise attack”. Significantly, Shute’s future war, set in 1963, wasn’t triggered by the usual NATO-Warsaw Pact arsenals of nuclear weapons, but the proliferation of them elsewhere. Then, as now, it is not Russian or Chinese aggression that should worry those with nightmares of nuclear cataclysm, but that of other countries. Thanks to the NPT, IAEA and the UN, these possibilities are contained. Today, the world’s weapons of mass destruction stand at one tenth of their number during the Cold War.

Indeed, the very origins of the current Ukraine crisis illustrate how the international order has managed to contain potential proliferation. When the Soviet Union disintegrated in 1991, Ukraine possessed the world’s third largest nuclear arsenal, greater than those of Britain, France and China combined. Kyiv soon realised it couldn’t afford to maintain the warheads and remain a credible nuclear military power. A solution was found, whereby the weapons would be destroyed, but only in exchange for security assurances that the United States and Russia would respect Ukraine’s independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity.

What Ukraine signed on 5 December 1994 was the Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances, in which Bill Clinton for the United States, Boris Yeltsin for Russia and John Major for Great Britain promised to protect Ukraine and its territorial integrity in recognition of Kyiv surrendering the protection of its nuclear arsenal. There was no mention of military guarantees, which Ukraine assumed were implied. Additionally, Kyiv promised to adhere to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

After the annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014, the G7 nations complained that Russia had breached the Budapest Memorandum. Vladimir Putin replied evasively that since, in his view, a new regime had seized power from Ukraine’s previously pro-Moscow premier Viktor Yanukovych, “Russia has not signed any obligatory documents with this new state”. Since then, Russia has lied and prevaricated over its betrayal of Budapest. In 2016, Sergey Lavrov went so far as to claim, “Russia never violated Budapest memorandum. It contained only one obligation, not to attack Ukraine with nukes” — a gross distortion of the Memorandum’s many obligations.

However, the West responded in 2014 only with mild economic sanctions. Arguably, the apathy of the anti-interventionist Barack Obama and David Cameron, influenced by a London awash with Russian money, emboldened Vladimir Putin. Few experts disagree that had the West responded in 2014 as they did in 2022, Russia’s expansionist ambitions into Ukraine would have ended long ago. Yet, there is plenty of room for optimism. The Russo-Ukraine conflict has not spread because of the international order and its treaties. Apart from North Korea and Iran, neither of whom have quite perfected their devilish devices, nuclear proliferation of third parties has been held in check.

The Kremlin shows no sign of taking steps to escalate to a nuclear level. It is not in its interests, or those of its allies, to do so. None of the 32 nations who recently abstained from condemning Russia in the 24 February UN vote would welcome Vladimir Putin and his cronies flinging nukes around. The qualified support of major powers like China, India and Pakistan is attached to the cheap oil and arms procurements they have negotiated with Moscow. Any hint of Tsar Vladimir “going nuclear” would see their abstentions morph into support for the West. Putin, for all his rhetoric, cannot afford to go it alone with just the six who voted with him at the UN. In military terms, they offer nothing.

The world’s various international arms treaties provide plenty of optimism that this will remain a regional war. So far, Putin’s threats have melted away as the morning mist. The scenario he implies, akin that in On the Beach and other nuclear-war-scare novels and films, is so unlikely as to be discounted. They and all the rest of the post-apocalyptic genre are written as nail-biting entertainment, not history or current affairs.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Putin, Shute and nukes”, The Critic, 2023-03-09.

June 21, 2023

Was Starship’s Stage Zero a Bad Pad?

Practical Engineering

Published 20 Jun 2023Launchpads are incredible feats of engineering. Let’s cover some of the basics!

Unlike NASA, which spends years in planning and engineering, SpaceX uses rapid development cycles and full-scale tests to work toward its eventual goals. They push their hardware to the limit to learn as much as possible, and we get to follow along. They’re betting it will pay off to develop fast instead of carefully. This video compares the Stage 0 launch pad to the historic pad 39A.

(more…)

Scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow, Orkney, 21 June 1919 in the Great War

CEFRG (Canadian Expeditionary Force Research Group)

Published 3 Apr 2020The German High Seas Fleet decided to sink as many of its own ships as possible to prevent them from falling into Allied hands. In total, 52 of 74 ships were sabotaged to keep them from Britain, France, Italy and the USA. Most of these nations wanted a share for their navies, and knowing she could not have them all to herself, Britain wanted the ships scrapped to prevent other nations from gaining naval superiority.

On the morning of 21 June 1919, the British fleet left Scapa Flow for exercises, and Rear Admiral Sydney Freemantle, commander of the 1st Battle Squadron guarding the ships, planned to return two days later to board and seize the ships.

Already occupying Germany west of the Rhine, the Allied Powers expected Germany to accept all articles of the Treaty of Versailles by 23 June, and threatened to occupy territory east of the Rhine if all demands were not met. German Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, following orders he had received after the breakdown of negotiations, seized the opportunity with the British fleet having just left the harbour, gave the order to scuttle all ships as his crews opened seacocks, torpedo tubes and portholes to flood them, and once again hoisted the flag of the Imperial German Navy.

The final battle casualties of the Great War occurred on this day, with nine German sailors killed and sixteen wounded by the British during brawls when they refused to help save the ships. For his part, von Reuter was imprisoned along with 1,800 of his men, but was released the following year. Upon his return to Germany, he was praised as the man who had preserved the honour of the German High Seas Fleet (in typical fashion, Freemantle had angrily accused von Reuter of having behaved without honour).

Of the 52 ships scuttled in 1919, seven remain at the bottom of the sea today. They are registered under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979, and provide some of the best shipwreck diving in Europe.

QotD: Working online

After a bit of a rocky start, most people I know who suddenly found themselves doing their “work” online quickly realized little work they actually did — and, by extension, since they were the conscientious ones, how trivially little work so many of their coworkers did. Hard on the heels of that was the realization that “work” in a physical workplace, for the vast majority of people, really means “socializing”. There are a LOT of jobs in which one person actually working from home can accomplish in one day what it takes an entire “customer service” department a week to do under “normal” — meaning, “in the office” — conditions.

[…]

For lots of people, the office was their only social outlet. Coffee breaks, water cooler chatter, happy hours … for lots of people, that was pretty much it, socially. “Work/life balance” was always a joke, because all your friends are work friends, so even if you’re “socializing” and not “working”, it’s with the same people from the office, talking about office stuff. And the longer you stayed in the same job, the higher up the corporate ladder you got, the more specialized your position, the worse it got – your rookie customer service reps still had buddies from college to hang out with, but junior managers tended to hang out exclusively with other junior managers, etc. The “professions”, of course, are famously clannish — the only ways to talk to a lawyer or doctor are to hire one, or be one.

Severian, “More Scattered Thoughts”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-13.

June 20, 2023

“Mendicino is a dead minister walking, and we suspect he knows it”

Belated (from me, not from them) section from this weekend’s update from the editors at The Line:

Though you may find this hard to believe, based on what’s above, we were paying attention to some other things this week. The Ottawa vortex of ridiculousness continued at its usual clip. The government continues to try and find a defensible position on Paul Bernardo’s prison transfer to a medium-security prison. Alas for Mr. Trudeau, he’s been hit by a double-whammy of bad luck. Bernardo is an emotional trigger point with probably no rival across Canada. And the PM’s point man on this file is the hapless (!) Marco Mendicino, minister of Public Safety.

Let’s be clear: your Line editors are far too Vulcan-like to possess strong feelings about the transfer of Bernardo. We are of the right age to have grown up during the era of the Bernardo rapes, murders and eventual trial. He was the boogeyman of our youth. That being said, the important thing is that he dies miserable and alone behind bars. We aren’t particularly invested in which particular prison this happens. If there was a sensible reason for him to be moved to the Quebec facility, hey, whatever. He can rot in any suitable prison as far as we’re concerned.

The issue here, and it’s ridiculous that we have to spell this out, isn’t the transfer itself. Nor are we calling upon Trudeau or the federal government to become intimately involved in decision-making for prisoners, even high-profile ones. The only thing that turned this into a huge story was the latest peek it gave us into the Trudeau government. We have been confronted with — surprise! — more incompetence and dysfunction.

Mendicino’s staff had been repeatedly told about the pending transfer; no one told the boss. The PMO had been told, too. No one told that boss, either. Why tell the boss? So that they don’t get caught flatfooted by a scandal. This is basic issues management and internal communications, and we’re being shown, yet again, that the government is terrible at this. And, absurdly, Mendicino apparently has some of the best and brightest providing the adult supervision he so clearly needs: veteran political staffers were sent to his office after he beclowned himself during the gun-control fiasco a few months ago.

And this is the problem. We don’t care which cell holds Bernardo as he slides closer to hell. We do care about yet another data point in a pattern that has emerged with this government: they aren’t on top of their files, their offices aren’t well run, ministers aren’t properly briefed, and there seems to be zero accountability anywhere in this process. It was left to the Ottawa Parliamentary Press Gallery to hunt down Mendicino like ravenous cheetahs on a wayward gazelle after Mendicino had promised to brief them, and then no-showed. He also promised to brief them again later on Thursday, and failed to show up that time, too.

We know, we know. It’s hard to believe he’d lie. Marco Mendicino? An incompetent bullshitter? Say it ain’t so.

Mendicino is a dead minister walking, and we suspect he knows it. The government is obviously hell bent on getting to the summer break without sacking the minister, because to sack him, despite his manifest and repeated failings, would be to admit said failings, and this government will never do that. If they can get to the break, they can shuffle him off to the sweet oblivion of an obscure ministry, or even the back benches later on this summer. This is just the latest example of what Line editor Gerson has observed about these guys: tactically smart, but strategically dumb.

And, ahem, call us hopelessly naïve, but maybe the politics isn’t the point here? Canadians ought to have someone in the job of Public Safety minister — kind of an important role, you’ll agree — who is competent and well-supported by excellent staff. Instead we get this shitshow and frantic politicking to avoid handing the opposition a one-day media-cycle victory. It’s a bad look on the government. But it’s nothing we didn’t already know, we guess. They aren’t here to serve Canadians. They’re here to save themselves.