In the weekly dispatch from The Line, the editors defend the honour of the original Gong Show and say that it’s not fair or right to compare that relatively staid and dignified TV show to the Canadian government’s performance art on the foreign interference file:

When the news broke late Friday afternoon that David Johnston was resigning from his position as special rapporteur on Chinese interference, the general reaction across the chattering class was a variable admixture of amusement and scorn. There’s probably a German word for it, but the security and intelligence expert Wesley Wark captured the tone of it with the headline on his Substack post, which said, simply: “Gong Show“.

We’re somewhat inclined to concur with Wark, except the three-ring train wreck that has marked Johnston’s time as Justin Trudeau’s moral merkin has been so disastrous that we think apologies are due to Chuck Barris, in light of the relative sobriety of his famous game show.

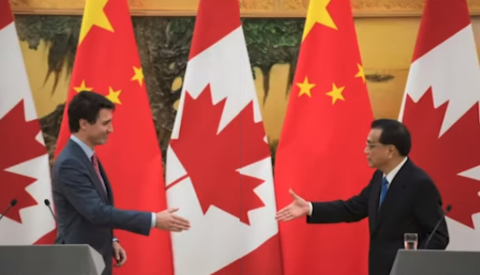

Reporters at the Globe and Mail and Global News started breaking stories about Chinese interference in Canadian elections a few months back, based largely on leaks from inside the Canadian intelligence apparatus. Almost immediately it was clear that the Liberals had a major problem on their hands, one that was going to require levels of transparency, good judgment and political even-handedness that this government has manifestly failed to achieve during its almost eight years in power.

Yet when Trudeau announced that he was going to appoint an “eminent Canadian” as “special rapporteur” to do an investigation and report back to the government with recommendations for how it should tackle the issue, we gave a collective groan here at The Line. Given the endless similar tasking of retired Supremes passim, it was clear that the pool from which Trudeau was going to fish his eminent personage was very shallow, and pretty well-drained. Indeed, at least one of us here was willing to bet large sums that it would be David Johnston.

What do we make of all this? Here’s the situation as we see it, in bullet form for brevity’s sake:

- Johnston should never have been offered the position of special rapporteur

- Having been offered the job of special rapporteur, Johnston should never have accepted it

And that is basically it. But given that Trudeau had the poor judgment to ask him, and Johnston had the poor judgment to accept, we think everything that has happened since was pretty much inevitable. We couldn’t have guessed at all the details of how this would have played out, especially the delicious elements beginning with the decision to hire Navigator to provide strategic advice (to manage what, exactly?), the revelation that Navigator had also provided strategic advice to Han Dong (who, recall, Johnston more or less exonerated), the firing of Navigator and the involvement of Don Guy and Brian Topp … this is really just gongs piled upon gongs piled upon gongs.

But the overall trajectory of Johnston’s time as special rapporteur? If you had told us ahead of time that this was more or less how things would go, we wouldn’t have been much surprised. Why? Because we live in Canada. And this is how Canada’s governing class behaves. It is a small, incestuous, highly conflicted and enormously self-satisfied group of people that is so isolated from the rest of the country they don’t even realize how isolated they are.

Honestly. What in heaven’s name gave Trudeau the idea that it would be smart to ask a former governor general to help launder his government’s reputation? And why on Earth did Johnston think it was a good idea to accept? Forget the Navigator stuff, this turkey was never going to fly. Johnston’s report was not accepted as the wise counsel of a wise man; instead it was seen as a partisan favour by a conflicted confidant. Sure, Johnston was subject to some pretty unfair attacks from the opposition, but what did he think was going to happen? Has he paid any attention over the last decade? But pride is a form of stubborness, and even after parliament voted for him to go, Johnston insisted he would stay on to finish his work. Until, on Friday afternoon, he decided he would not.

We’re not going to speculate about why Johnston finally pulled the chute. We’d like to think that the former GG in him thought it best to obey the will of the House of Commons. We rather hope it had nothing to do with some pointed (and unanswered) questions put to Johnston’s office by the Globe and Mail, asking whether Navigator had been given a heads-up on Johnston’s conclusions on the Dong file.

Maybe it doesn’t matter. As Paul Wells put it in a recent column, Trudeau sought to “outsource his credibility by subcontracting his judgment,” where credibility was supposed to flow from Johnston to Trudeau. Instead, and we would say, inevitably, the flow went in the opposite direction. If the prime minister had any credibility to lead the country on this issue, he wouldn’t need a special rapporteur in the first place. The fact that Trudeau felt the need to appoint one is a tacit admission that he knows he doesn’t have the trust of the people.

And that is the real problem here. The Johnston saga has ended where it was always going to, with a once-honorable man’s reputation in tatters and the problem he was brought in to address still unresolved. David Johnston has resigned, as he must have. In our view, that’s one resignation too few.