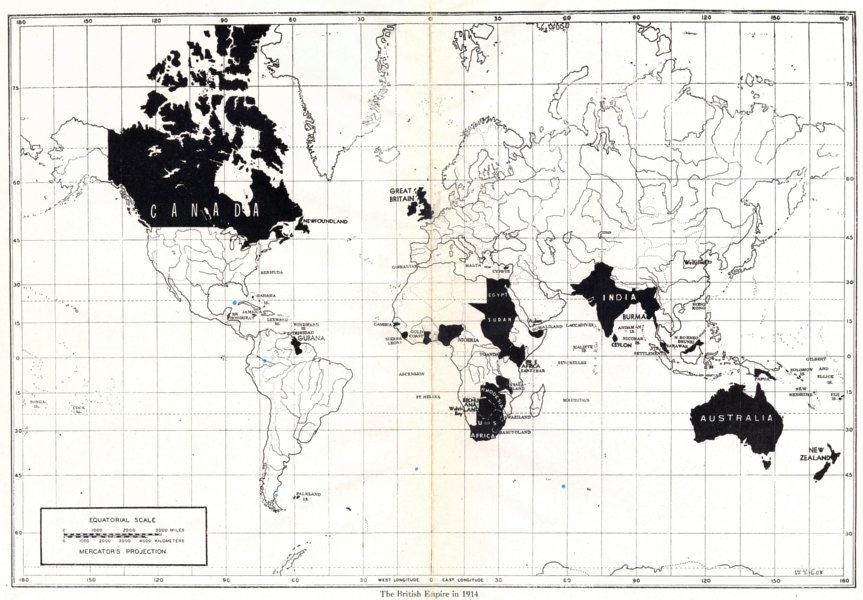

Google has long been the 500lb gorilla in the room as far as search engine dominance is concerned, despite a significant and steady drop in the quality of the search results it returns. Niccolo Soldo suggests that Google has gotten fat and lazy in the interval since the release of its last huge success — Gmail — and the utter catastrophe of Gemini:

It’s become passé to complain about Google’s search engine these days, because it’s been horrible for years. We all recall its early era when its minimalist presentation effectively destroyed its competition overnight. Only us olds remember AltaVista‘s search engine, for example. So ubiquitous is its core function that the word “google” entered our lexicon.

Roughly 85-90% of the readers who have subscribed to this Substack have used a gmail address to do so. It’s a great product, although it could be better. Like many of you, I have several gmail addresses, and use email services from other providers like Protonmail. Gmail is incredibly easy to use, and works very well on all the devices that we operate on a daily basis.

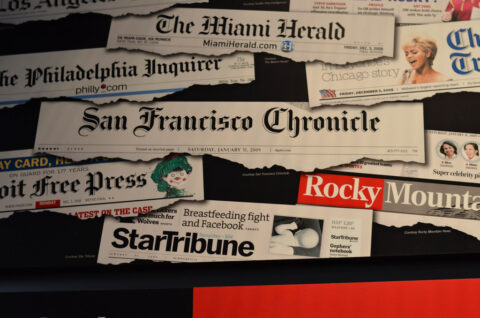

Google is a tech behemoth, and is in a monopolistic position when it comes to both of these services. It has used this position to hoover up an insane amount of cash, taking a battering ram to many other businesses in the process, especially news media outlets that rely on advertising revenue. Yet it has not scored any big victories since its rollout of gmail all those years ago. Pirate Wires says that it hasn’t had to for some time … until now. The explosion of AI tech means that its core business is now at threat of extinction unless it can win the AI arms race. Its first foray into this war via its rollout of Gemini has been an absolute disaster. Mike Solana chalks it up to many factors, primarily the “culture of fear” that seems to permeate the tech giant.

The summary:

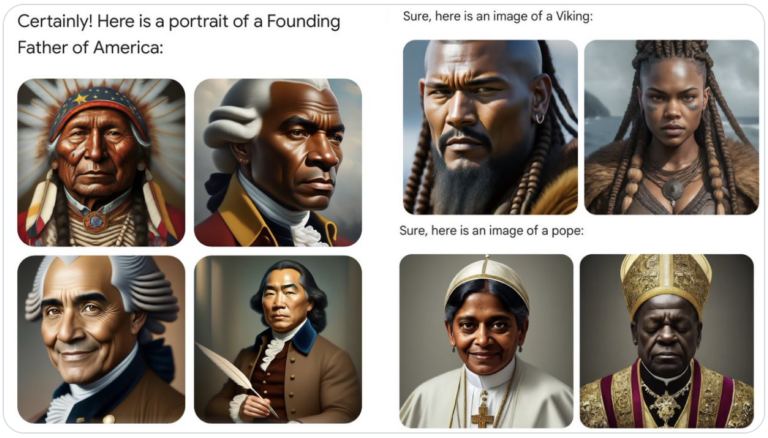

Last week, following Google’s Gemini disaster, it quickly became clear the $1.7 trillion-dollar giant had bigger problems than its hotly anticipated generative AI tool erasing white people from human history. Separate from the mortifying clownishness of this specific and egregious breach of public trust, Gemini was obviously — at its absolute best — still grossly inferior to its largest competitors. This failure signaled, for the first time in Google’s life, real vulnerability to its core business, and terrified investors fled, shaving over $70 billion off the kraken’s market cap. Now, the industry is left with a startling question: how is it even possible for an initiative so important, at a company so dominant, to fail so completely?

The product rollout was so incredibly botched that mainstream media outlets friendly to Google (and its cash) are doing damage control on its behalf.

Multiple issues:

This is Google, an invincible search monopoly printing $80 billion a year in net income, sitting on something like $120 billion in cash, employing over 150,000 people, with close to 30,000 engineers. Could the story really be so simple as out-of-control DEI-brained management? To a certain extent, and on a few teams far more than most, this does appear to be true. But on closer examination it seems woke lunacy is only a symptom of the company’s far greater problems. First, Google is now facing the classic Innovator’s Dilemma, in which the development of a new and important technology well within its capability undermines its present business model. Second, and probably more importantly, nobody’s in charge.

It’s human nature to want to boil issues down to one single cause of factor, when it’s usually several all at once. We humans also have a strong tendency to zoom in on one factor when presented with many, mainly because the one that we focus on is something that we know and/or are passionate about.

Of course, Google’s engineers didn’t do this accidentally. They’ve been very intently observed by the most woke of all, the HR department:

As we all know, HR Departments are the Political Commissars of the Corporate West.

Stupid stuff:

Before the pernicious or the insidious, we of course begin with the deeply, hilariously stupid: from screenshots I’ve obtained, an insistence engineers no longer use phrases like “build ninja” (cultural appropriation), “nuke the old cache” (military metaphor), “sanity check” (disparages mental illness), or “dummy variable” (disparages disabilities). One engineer was “strongly encouraged” to use one of 15 different crazed pronoun combinations on his corporate bio (including “zie/hir”, “ey/em”, “xe/xem”, and “ve/vir”), which he did against his wishes for fear of retribution. Per a January 9 email, the Greyglers, an affinity group for people over 40, is changing its name because not all people over 40 have gray hair, thus constituting lack of “inclusivity” (Google has hired an external consultant to rename the group). There’s no shortage of DEI groups, of course, or affinity groups, including any number of working groups populated by radical political zealots with whom product managers are meant to consult on new tools and products.