World War Two

Published 11 May 2024Germany signs not one, but two unconditional surrenders and the war in Europe is officially over … although that does not mean that all the fighting in Europe is, for there is fighting and surrenders all over Europe all week. The Japanese launch a counteroffensive on Okinawa; the Chinese launch one in Western Hunan; the Australians advance on Borneo and New Guinea; and the fight continues on Luzon in the Philippines, so there is still an awful lot of the world war to come, even with the end of the war in Europe.

00:00 Intro

00:40 The German Surrender

03:23 Fighting And Surrenders In The East

06:53 The Prague Uprising

15:50 The Last Surrenders In Europe

18:42 The Polish Situation

20:25 The War In China And The South Seas

23:17 Summary

24:44 Conclusion

(more…)

May 12, 2024

Germany Surrenders! – WW2 – Week 298 – May 11, 1945

May 5, 2024

Allied Victory in Berlin, Italy, and Burma! – WW2 – Week 297 – May 4, 1945

World War Two

Published 4 May 2024So much goes on this week, and this is the longest episode of the war by like 15 minutes. But there’s so much to cover! The Battle of Berlin ends; the war in Italy ends; the war in Burma ends- well, it ends officially, though there are still tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers scattered around Burma. And there’s a whole lot more to these stores and a whole lot more stories this week in the war. You can’t miss this one.

01:27 The End of the War in Italy

03:40 Western Allied Advances

07:02 Relief Operations in the Netherlands

15:45 Hitler’s Death and the Surrender of Berlin

24:20 Walther Wenck’s Retreat

28:00 The Polish Situation

31:09 What About Prague?

32:44 The End of the Burma Campaign

36:04 THE FIGHT FOR TARAKAN ISLAND BEGINS

37:24 Okinawa

40:11 Other Notes

41:04 Summary

41:43 Conclusion

(more…)

April 29, 2024

“The disaster at Imphal was perhaps the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war”

Dr. Robert Lyman makes the case for the Japanese defeat at the battles of Imphal and Kohima being one of the four great turning points in the Second World War:

It is clear to me that the great twin battle of Imphal & Kohima, which raged from March through to late July 1944, was one of four great turning-point battles in the Second World War, when the tide of war changed irreversibly and dramatically against those who initially held the upper hand.

The first great turning point was arguably at Midway in June 1942 when the US Navy successfully challenged Japanese dominance in the Pacific. The second was at Stalingrad between August 1942 and January 1943 when the seemingly unstoppable German juggernaut in the Soviet Union was finally halted in the winter bloodbath of that city, where only 94,000 of the original 300,000 German, Rumanian and Hungarian troops survived. The third was at El Alamein in October 1942 when the British Commonwealth triumphed against Rommel’s Afrika Korps in North Africa and began the process that led to the German surrender in Tunisia in May 1943. The fourth was this battle, that at Kohima and Imphal between March and July 1944 when the Japanese “March on Delhi” was brought to nothing at a huge cost in human life, and the start of their retreat from Asia began. Adjectives such as “climactic” and “titanic”, struggle to give proper impact to the reality and extent of the terrible war that raged across the jungle-clad hills during these fearsome months.

That the Japanese were contemplating an offensive against India in early 1944 was a surprise to Allied planners, who had given no thought to its possibility. By this time Japan had reached the apogee of its power, having extended the violent reach of its Empire across much of Asia since it launched its first surprise attacks in late 1941. Its initial surge in 1942 into what was briefly to be Japan’s “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” was as dramatic as it was rapid and two years further on several millions of peoples across Asia laboured under its heavy yoke. But by early 1944 the tide had turned decisively in the Pacific, the American island-hopping advance reaching steadily but surely towards Japan itself, its humiliated enemies fighting back with desperation, and with every ounce of energy they could muster. They were beginning to prevail in the fight although the struggle on the landmass of Asia was a strategic sideshow in the context of a global conflict: at this time the British and American High Commands were totally occupied with Europe and the Pacific. The British and Americans were preparing for D Day. The Soviets were advancing in Ukraine. There was a stalemate in Italy at Monte Cassino. The Americans were preparing to land in the Philippines. Germany and Japan were both in retreat, but not defeated. In this global context India and Burma appeared strategically peripheral, even inconsequential. Yet in this month, at a time when on every other front the Japanese were on the strategic defensive, Japan launched a vast, audacious offensive deep into India in an attack designed to destroy for ever Britain’s ability to challenge Japan’s hegemony in Burma.

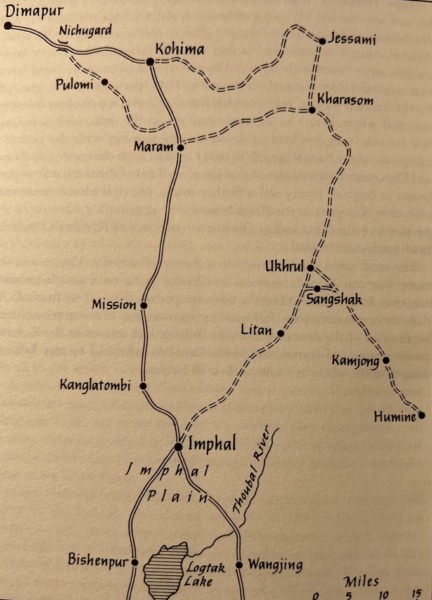

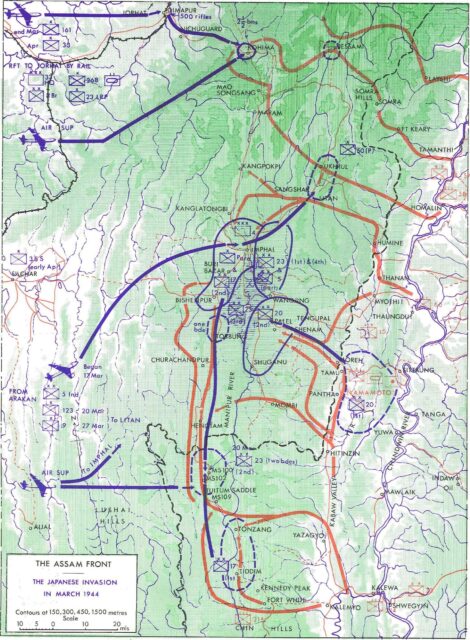

The Japanese commander was General Mutaguchi Renya, a gutsy go-getter who had played a significant role in the collapse of Singapore in February 1942. His evaluation of the British position in northeast India revealed that the three key strategic targets in Assam and Manipur were Imphal; the mountain town of Kohima, and the huge supply base further back on the edge of the Brahmaputra Valley at Dimapur. If Kohima were captured, Imphal would be cut off from the rest of India by land. From the outset Mutaguchi believed that with a good wind Dimapur, in addition to Kohima, could and should be secured. He reasoned that capturing this massive depot would be a devastating, possibly terminal blow to the British ability to defend Imphal, supply the Americans in Northern Burma under Vinegar Joe Stilwell, support the Hump airlift into China and mount an offensive into Burma. It would also enable him to feed his own, conquering army, which would advance across the mountains from the Chindwin on the tightest imaginable supply chain. With Dimapur captured, the Japanese-led Indian National Army under the Bengali nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose could pour into Bengal, initiating the long-awaited anti-British uprising.

The essence of the battle for India in 1944 can be quickly told. Mutaguchi’s 15th Army advanced in four separate columns into Manipur. The Japanese made determined, even desperate, efforts to seize their objectives: in the north Kohima, with a scratch British and Indian garrison of 1,200 trained fighting soldiers – about two thirds of them Indian – was attacked by an entire division of about 15,000 men in early April. Surrounded and slowly forced back onto a single hill they were supplied by air until relief came on 20 April, although the battle to dislodge the Japanese from Kohima continued bloodily, in appalling weather and battlefield conditions – the annual monsoon was in full spate – through to early June. Further south the Japanese plan entailed attacking Imphal from north, east and south. The plan of the commander of the 14th Army, Lieutenant General Bill Slim, was to withdraw his forces into the hills and there to allow the Japanese to expend themselves fruitlessly against well-supplied and aggressive British bastions, equipped with tanks, artillery and supported by air. The battle for Imphal in Manipur and for Kohima to the north-west in the neighbouring Naga Hills settled down to a bloody hand-to-hand struggle as the Japanese tried to gain the foothold necessary for their survival. They travelled lightly, and reserves soon exhausted themselves and further supplies were almost non-existent. Just as the air situation was becoming critical for Slim through poor weather and shortages of aircraft the relieving division from Kohima – the British 2nd Infantry Division that had last seen action at Dunkirk – began fighting its way towards Imphal, and the four beleaguered divisions began to push out from the Imphal pocket. By 22 June the 2nd Division and the 5th Indian Division met north of Imphal and the road to the plain was open. Four weeks later the Japanese withdrawal to Burma began.

Of all the invading armies of history, it is hard to think of one that was repulsed more decisively, or more ignominiously, than the Japanese 15th Army launched against India in March 1944. Its defeat was not the fault of the Japanese soldiers, who fought courageously, tenaciously and fiercely, but of their commanders, who sacrificed the lives of their troops on the altar of their own hubris. The battle had provided the largest, most prolonged and most intense engagement with a Japanese army yet seen in the war. “It is the most important defeat the Japs have ever suffered in their military career” wrote Mountbatten exultantly to his wife on 22nd June 1944, “because the numbers involved are so much greater than any Pacific Island operation.” The extent of the disaster that befell the 15th Army is captured by a comment by Kase Toshikazu, a member of the wartime Japanese Foreign Office, who lamented: “Most of this force perished in battle or later of starvation. The disaster at Imphal was perhaps the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war.” The latter might better have included the caveat “Japanese” to avoid charges of exaggeration, but his comment captures something of the enormity of the human disaster that overwhelmed the 15th Army. It might more fairly be described as the greatest Japanese military disaster of all time. The Indian, Gurkha, African and British troops of this remarkably homogeneous organisation had also decisively removed any remaining notions of Japanese superiority on the battlefield.

The importance of this victory was overshadowed at the time, and downplayed for decades afterwards, by the massive victories in 1945 which brought World War II to an end in Europe and the Pacific. But this lack of publicity and of awareness does not remove the fact that, objectively speaking, the battles in India in 1944, epitomized in the fulcrum battle at Kohima, were an epic comparable with Thermopylae, Gallipoli, Stalingrad, and other better known confrontational battles where the arrogant invader became, in time, the ignominious loser.

April 28, 2024

The Battle of Berlin! – WW2 – Week 296 – April 27, 1945

World War Two

Published 27 Apr 2024The battle for the German capital rages on all week, as the Soviets get ever closer to the Reich Chancellery, under which lies Hitler’s bunker. Berlin is surrounded, but can it be relieved? There are also Allied advances in East Prussia, Czechoslovakia, and in Western Germany, but beyond that, it looks like the Axis lines have completely collapsed in Italy. The Allies are also advancing — and quickly — in Burma toward Rangoon, though not much at all on Okinawa, and it is the Japanese who are on the move in Western Hunan. It’s a real rollercoaster of a week.

Chapters

01:10 Recap

01:43 Soviets fight their way into Berlin

07:45 Berlin surrounded

10:28 Rokossovsky advances

12:48 Göring and Himmler betray Hitler

13:57 Fighting on the Eastern Front

15:23 Allied advance in the West

15:51 German collapse in Italy

17:31 4th Corps racing through Burma

19:36 The Battle of Western Hunan

21:40 Okinawa and the Philippines

22:59 Notes

23:59 Conclusion

(more…)

April 27, 2024

“… when it comes to energy policy Germany is an undisputed champion of crazy”

eugyppius explains how Angela Merkel’s government reacted to the Japanese Fukushima disaster in a sane, measured, and sensible way … naw, I’m pulling your leg. They looked at all the options and then selected the dumbest possible reaction available to them:

German anti-nuclear protest in Cologne, 26 March 2011.

Photo by Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Nordrhein-Westfalen via Wikimedia Commons.

All of our countries are crazy in various ways, but when it comes to energy policy Germany is an undisputed champion of crazy.

In 2011, a tsunami caused the Fukushima nuclear disaster. If you check a map, you’ll notice that Fukushima is in a country called Japan, which it turns out is a different country from Germany. The Fukushima disaster had zero to do with the Federal Republic, but then-Chancellor Angela Merkel felt the need to solve the problem of Fukushima by phasing out nuclear power in Germany, even though tsunamis and earthquakes are not a problem in Germany, because Germany is a country in Central Europe and not an island nation in Asia.

That is crazy enough, but it gets much crazier. Months before announcing the nuclear phase-out, Merkel’s government had passed energy transition legislation to secure Germany’s path towards a zero-emissions future. We resolved to ditch our most significant source of emissions-free power, in other words, just months after resolving an energy transition to emissions-free power. At this point you would be justified in wondering if Germany suffers from some kind of shamanistic cultural phobia of electricity in general, that is how crazy this is. These insane choices had the near-term consequence of increasing our dependence on Russian natural gas. Otherwise, they ensured that power generation in Germany would be vastly more expensive than necessary and also vastly more carbon intensive than necessary.

Now, crazy demands explanations, and observers have proposed various theories for the German climate nuclear crazy. Two of them deserve mention here:

1) The 1968 generation in Germany suffered from unusual radicalism, sharpened by moral anxiety over National Socialism, and resolved to outcompete all others in the project of self-abnegating virtue. Our culture developed a deranged anti-nuclear movement that in a fit of typical German thoroughness also came to embrace opposition to nuclear power. The Chernobyl disaster radicalised the pink-haired anti-nuclearists still further, and these cretins grew up to become news anchors, school teachers and book authors, effectively indoctrinating the next generation according to their parareligious delusions.

2) German politicians after the Cold War – especially Gerhard Schröder and Angela Merkel – harboured a subtle and not entirely unreasonable desire to strengthen ties with resource-rich Russia. They decided that the anti-nuclearists and the Green Party could be instrumentalised towards this end. The energy transition and the nuclear phase-out increased our dependence on Russian gas, and this was a feature more than it was a bug.

These are mutually supporting theories, but I don’t think either of them can fully account for the bizarre phenomenon before us. Germany energy crazy is a very deep problem and it will keep historians busy for many generations.

In 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, and Germany under Merkel’s successor, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, decided along with the rest of the liberal West that Russia was bad, bad, bad and that evil Putin had to be punished with self-immolating sanctions, sanctions, sanctions. This new spasm of high-minded moralising further attenuated our energy situation, ushering in an entirely self-made energy crisis. The Greens, now in government, were determined to proceed with the last stages of the nuclear phase-out, even with our natural gas supplies in doubt. Only when they saw themselves staring into the abyss of political doom did they grudgingly agree to give our last nuclear plants a three-and-a-half month lease on life. We Germans and our energy policy had out-crazied everyone else, we had made ourselves the laughing stock of the entire world, that is how crazy we were.

April 26, 2024

QotD: The secret rulers of Japan

Okay, but how well does that version of history line up with the reality of Japanese government in the second half of the 20th century? Johnson brings a lot of evidence to back up his claim that Japan is still secretly ruled by the bureaucracies, chief among them MITI. He points out, for example, that hardly any bills proposed by individual legislators and representatives go anywhere, while bills proposed by MITI itself are almost always instantly approved by the parliament. But MITI’s authority isn’t limited to the government, it’s pretty clear that they control the entire private sector too. That might seem tautological — if MITI’s will always becomes law, then they can unilaterally impose new regulations or mandates that can destroy any company, with zero recourse, so everybody will naturally do what MITI says. But it’s subtler than that — the real mechanism is tangled up in MITI’s dynastic and succession customs.

Remember, this may look like an economic planning bureaucracy, but it’s actually a secret samurai clan. So they’re constantly doing the kinds of stuff that any good feudal nobility does. For instance, the economic planning bureaucrats frequently cement their treaties by marrying off their sister/daughter/niece to a mentor or to a protegé. They also sometimes legally adopt each other, ancient Roman-style. Naturally they also have an extremely complicated set of rules governing their internal hierarchy, rights of deference, etc. But remember, this isn’t just a secret samurai clan, it’s also a government agency! Agencies have rules too — explicit rules written down in binders, rules governing promotion and succession and all the rest. Sometimes, the official rules and the secret rules conflict, butt against each other, and out of that friction something beautiful emerges.

The highest rank in MITI is “Vice-Minister” (the “Minister” is one of those elected political guys who don’t actually matter). But it’s also the case that somebody who’s been at MITI longer or who’s older than you (these are actually the same thing, because everybody joins at the same age) is strictly superior to you in seniority. But that can create a paradox! What happens if a young guy becomes Vice-Minister? He would then be more senior than his older colleagues by virtue of office, but they would be more senior by virtue of tenure, and that would mean either an official rule or a secret rule being broken. To resolve this impossible conflict, the instant a new Vice-Minister is selected, everybody who’s been in the bureaucracy longer than him resigns immediately, so that his absolute seniority is unambiguous and unquestionable. And then … the first act of the new Vice-Minister is to give everybody who fell on their swords powerful jobs as executives and board members of the biggest Japanese corporations. The entire process is called amakudari, which means “descent from heaven”.

Amakudari is really a win-win-win-win: the new Vice-Minister has unchallenged power within the agency and a whole host of new friends in the private sector, the guys who resigned all have cushy new jobs that come with better pay and perks, the companies that are descended upon now have an employee with great connections to the agency that controls their fates, and MITI as a gestalt entity can spread its tentacles throughout the economy, aided by cadres of alumni who think its way and help translate policy into reality.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: MITI and the Japanese Miracle by Chalmers Johnson”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-04-03.

April 22, 2024

Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Because Of China?

Real Time History

Published Dec 1, 2023December 7, 1941: The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor shocked the world and brought the US into the Second World War. But why did the Japanese resort to such an attack against a powerful rival and what did it have to do with the Japanese war in China?

(more…)

April 21, 2024

300,000 Germans Surrender in the Ruhr – WW2 – Week 295 – April 20, 1945

World War Two

Published 20 Apr 2024The Soviet drive on Berlin continues, but it is now very much a race between the forces of Georgy Zhukov and those of Ivan Konev. In the west, over 300,000 Germans surrender to the Allies as the Ruhr Pocket is eliminated, though there are advances by all Allied armies this week on the whole Western Front. There is even an Allied breakthrough in Italy, though on Okinawa American attacks get nowhere. The Japanese are advancing in China, and in Burma the Allied drive for Rangoon continues.

(more…)

April 20, 2024

Cape Esperance and the Japanese Evacuation of Guadalcanal

Forgotten Weapons

Published Jan 12, 2024Today we return to Guadalcanal, to the site of the last actions of the campaign. For the Japanese, the defeat at Edson’s Ridge (aka Bloody Ridge) forced a disastrous and uncoordinated retreat into the jungle. With their supply lines destroyed, Japanese troops largely moved west on the island, away from American positions and in search of food. This would eventually bring them to Cape Esperance, where a rearguard force was landed, and some 10,652 Japanese soldiers were successfully evacuated on fast-moving destroyers over the course of several nights in early February, 1943.

On the American side, Army troops landed to relieve the Marines. In January and into early February they ran what was considered a mopping-up campaign west, including landings on the far west end of the island beyond Esperance. The intention was to encircle the remaining Japanese forces, under the assumption that the destroyer activity was landing fresh troops. Instead, when the American forces joined up at Cape Esperance it was an anticlimactic end to the fighting, as all they found were remnants of equipment that had been left on the beaches.

(more…)

April 14, 2024

Soviets Take Vienna and Königsberg – WW2 – Week 294 – April 13, 1945

World War Two

Published 13 Apr 2024The prizes of Vienna and Königsberg fall to the Soviets as they continue what seems an inexorable advance. In the West the Allies advance to the Elbe River, but there they are stopped by command. The big news in their national papers this week is the death of American President Franklin Roosevelt, which provokes rejoicing in Hitler’s bunker. The Allied fighting dash for Rangoon continues in Burma, as does the American advance on Okinawa, although Japanese resistance is stiffening and they are beginning counterattacks.

Chapters

00:32 Recap

01:05 Operation Grapeshot

01:57 Roosevelt Dies

06:01 Soviet Attack Plans for Berlin

12:45 Stalin’s Suspicions

14:31 The fall of Königsberg

17:02 The fall of Vienna

18:38 Japanese Resistance on Okinawa

20:34 The War in China

21:09 Burma and the Philippines

22:38 Summary

22:57 Conclusion

25:05 Memorial

(more…)

April 8, 2024

The Battle of Okinawa Begins – WW2 – Week 293 – April 6, 1945

World War Two

Published Apr 6, 2024It’s the next step toward invading Japan’s Home Islands — invading Okinawa, and it begins April 1st. Advances are easy by land, but at sea the kamikaze menace is in full swing. In Burma, plans are made to liberate Rangoon; in the west hundreds of thousands of Germans are surrounded in the Ruhr; and in the east, the Soviets begin assaults on Königsberg and Vienna.

(more…)

April 6, 2024

Italian Communists, the French in Indochina, and the fate of Italy’s army – WW2 – OOTF 34

World War Two

Published 5 Apr 2024What happened to Italian soldiers overseas after the fall of Mussolini? What about the French soldiers left over in Indochina after the Japanese “occupation by invitation”? And, what did the Allies think of the Italian Communist movement and its partisan forces?

(more…)

March 31, 2024

Allies Charge Forward from the Rhine! – WW2 – Week 292 – March 30, 1945

World War Two

Published 30 Mar 2024All along the Western Front the Allies break out in force, invading German territory and receiving German surrenders by the thousands. In the east, the Soviets take Danzig and Gdynia, and rout the Germans in Hungary. There’s a new Japanese offensive in China, though the fight on Iwo Jima ends with a Japanese defeat.

Chapters

00:45 Recap

01:08 Big Advances all over the West

05:48 Soviets take Gdynia and Danzig

07:09 Zhukov’s forces take Kustrin

10:39 The War in China

12:21 Iwo Jima Ends

14:30 Preliminaries for Okinawa

18:46 More Landings in the Philippines

19:23 Slim focuses on Rangoon

20:12 Notes to end the week

20:48 Summary

21:28 Conclusion

24:47 Call To Action

(more…)

August, 1945 – The Soviets enter the war in China

Big Serge outlines the Soviet invasion of Manchuria in August 1945 and its devastating impact on the Japanese Kwantung Army, finally shattering any remaining illusions that the Soviets would broker a peace between Japan and the western allies:

The Second World War had a strange sort of symmetry to it, in that it ended much the way it began: namely, with a well-drilled, technically advanced and operationally ambitious army slicing apart an overmatched foe. The beginning of the war, of course, was Germany’s rapid annihilation of Poland, which rewrote the book on mechanized operations. The end of the war — or at least, the last major land campaign of the war — was the Soviet Union’s equally totalizing and rapid conquest of Manchuria in August 1945.

Manchuria was one of the many forgotten fronts of the war, despite being among the oldest. The Japanese had been kicking around in Manchuria since 1931, consolidating a pseudo-colony and puppet state ostensibly called Manchukuo, which served as a launching pad for more than a decade of Japanese incursions and operations in China. For a brief period, the Asian land front had been a major pivot of world affairs, with the Japanese and the Red Army fighting a series of skirmishes along the Siberian-Manchurian border, and Japan’s enormously violent 1937 invasion of China serving as the harbinger of global war. But events had pulled attention and resources in other directions, and in particular the events of 1941, with the outbreak of the cataclysmic Nazi-Soviet War and the Great Pacific War. After a few years as a major geopolitical pivot, Manchuria was relegated to the background and became a lonely, forgotten front of the Japanese Empire.

Until 1945, that is. Among the many topics discussed at the Yalta Conference in the February of that year was the Soviet Union’s long-delayed entry into the war against Japan, opening an overland front against Japan’s mainland colonies. Although it seems relatively obvious that Japanese defeat was inevitable, given the relentless American advance through the Pacific and the onset of regular strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands, there were concrete reasons why Soviet entry into the war was necessary to hasten Japanese surrender.

More specifically, the Japanese continued to harbor hopes late into the war that the Soviet Union would choose to act as a mediator between Japan and the United States, negotiating a conditional end to war that fell short of total Japanese surrender. Soviet entry into the war against Japan would dash these hopes, and overrunning Japanese colonies in Asia would emphasize to Tokyo that they had nothing left to fight for. Against this backdrop, the Soviet Union spent the summer of 1945 preparing for one final operation, to smash the Japanese in Manchuria.

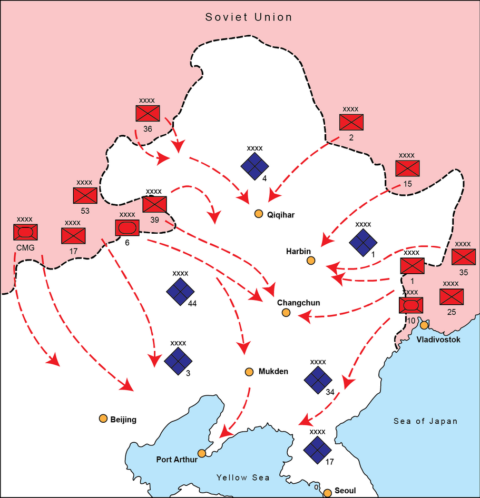

The Soviet maneuver scheme was tightly choreographed and well conceived — representing in many ways a sort of encore, perfected demonstration of the operational art that had been developed and practiced at such a high cost in Europe. Taking advantage of the fact that Manchuria already represented a sort of salient — bulging as it did into the Soviet Union’s borders — the plan of attack called for a series of rapid, motorized thrusts towards a series of rail and transportation hubs in the Japanese rear (from north to south, these were Qiqihar, Harbin, Changchun, and Mukden).

By rapidly bypassing the main Japanese field armies and converging on transit hubs in the rear, the Red Army would effectively isolate all the Japanese armies both from each other and from their lines of communication to the rear, effectively slicing Manchuria into a host of separated pockets.

There were, of course, a host of reasons why the Japanese had no hope of resisting this onslaught. In material terms, the overmatch was laughable. The Soviet force was lavishly equipped and bursting with manpower and equipment — three fronts totaling more than 1.5 million men, 5,000 armored vehicles, and tens of thousands of artillery pieces and rocket launchers.

The Japanese (including Manchurian proxy forces) had a paper strength of perhaps 900,000 men, but the vast majority of this force was unfit for combat. Virtually all of the Japanese army’s veteran units and equipment had been steadily transferred to the Pacific in a cannibalizing trickle — a vain attempt to slow the American onslaught. Accordingly, by 1945 the Japanese Kwantung Army had been reduced to a lightly armed and poorly trained conscript force that was suitable only for police actions and counterinsurgency against Chinese partisans.

Really, there was nothing for the Japanese to do. The Kwantung Army had far less of a fighting chance in 1945 than the Wehrmacht had in the spring of that year, and everyone knows how that turned out. Unsurprisingly, then, the Soviets broke through everywhere at will when they began the assault on August 9. Soviet armored forces found it trivially easy to overrun Japanese positions (armed primarily with archaic, low caliber antitank weaponry that could not penetrate Soviet armor even at point blank range), and by the end of the first day the Soviet pincers were driving far into the rear.

It is easy, in hindsight, to write off the Manchuria campaign as something of a farce: a highly experienced, richly equipped Red Army overrunning and abusing an overmatched and threadbare Japanese force. In many ways, this is an accurate assessment. However, what the offensive demonstrated was the Red Army’s extreme proficiency at organizing enormous operations and moving at high speeds. By August 20 (after only 11 days), the Red Army had reached the Korean border and captured all their objectives in the Japanese rear, in effect completely overrunning a theater that was even larger than France. Many of the Soviet spearheads had driven more than three hundred miles in a little over a week.

To be sure, the combat aspects of the operation were farcical, given the totalizing level of Soviet overmatch. Red Army losses were something like 10,000 men — a trivial number for an operation of this scale. What was genuinely impressive — and terrifying to alert observers — was the Red Army’s clear demonstration of its capacity to organize operations that were colossal in scale, both in the size of the forces and the distances covered.

More to the point, the Japanese had no prospect of stopping this colossal steel tidal wave, but who did? All the great armies of the world had been bankrupted and shattered by the great filter of the World Wars — the French, the Germans, the British, the Japanese, all gone, all dying. Only the US Army had any prospect of resisting this great red tidal wave, and that force was on the verge of a rapid demobilization following the surrender of Japan. The enormous scale and operational proclivities of the Red Army thus presented the world with an entirely new sort of geostrategic threat.

March 24, 2024

Chiang versus Mountbatten – WW2 – Week 291 – March 23, 1945

World War Two

Published 23 Mar 2024Chiang Kai-Shek is demanding his Chinese troops back from Burma, but this doesn’t fit well with Mountbatten’s plans for the region. In Burma, Bill Slim’s forces liberate Mandalay this week and make plans to head south for Rangoon. There’s also friction elsewhere in Allied command — between the Soviets and the Western Allies — over Italy. In the field in Europe, the Soviets advance all along the eastern front, and in the west, the Allies secure another Rhine crossing, and they also launch a double operation to send even more men across the river in force.

0:00 Intro

0:53 Recap

1:20 Iwo Jima

2:15 Plans for Okinawa

3:53 Mandalay liberated and plans for Burma

08:19 Allied Machinations about Italy

10:25 Soviet advances all along the Eastern Front

16:55 Plans for Operation Grapeshot

17:45 Four Allied Operations in the west

23:25 Summary + Conclusion

(more…)