At Watts Up With That?, Willis Eschenbach warns us yet again about believing headlines that say things like “Scientists Warn!”

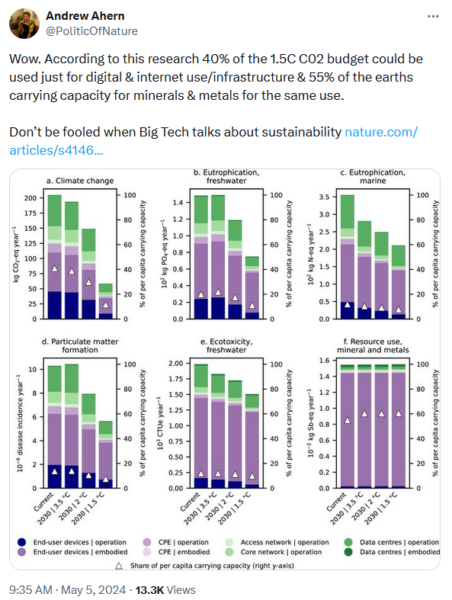

Only a journalist truly committed to the ancient art of panic-clickbait could squeeze all the world’s existential dread into a headline like, “A Giant, Destructive Volcanic Eruption Is Set to Shake the World in the Coming Months, Bringing About the End of Mankind, Scientists Warn“. They’ve accompanied it with the following graphic, in case you weren’t adequately terrified.

The dead giveaway? “Scientists Warn“. Whenever you see those two words sandwiched together above the fold, you know you’re about to step into a wonderland of wild extrapolation, qualified maybes, and models run so far into the future they boomerang back with “robots take over” as the y-axis.

They start out as follows:

A detailed geophysical study published in Nature in by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has refined our understanding of the Yellowstone supervolcano, uncovering new insights into its subsurface magma dynamics. Concurrently, climatological assessments by researchers such as Markus Stoffel (University of Geneva) have renewed discourse around the global systemic risks posed by a potential super-eruption — not only at Yellowstone, but at several other active volcanic complexes worldwide.

There’s an oddity here to start with. They’ve pushed together into one paragraph an actual scientific study of the Yellowstone caldera, and a paywalled puff piece by some random guy trying to frighten people about future eruptions. Unless you’re watching very closely to see which walnut the pea is under, it’s likely to be successful in making you think “Wow, a predicted super-eruption at Yellowstone, and the odds are high in other locations as well“.

Which does sound scary. So keep that thought in mind while we look at the first of the two parts they’ve pushed into one paragraph — the actual Yellowstone scientific study.

It’s the latest USGS study published in Nature under the very boring title “The progression of basaltic–rhyolitic melt storage at Yellowstone Caldera“. It gives us an upgraded, high-res CAT scan of Yellowstone’s magma plumbing. Instead of a giant pool of liquid doom sloshing under Wyoming, the new imaging shows a club sandwich: scattered blobs of partially molten rock, unevenly distributed, with most of the melt sitting in the northeast sector. The scale is impressive — 400–500 cubic kilometers of rhyolitic magma waiting for its cosmic moment. The heat just keeps bubbling up from below, slow and relentless, and with enough time, these melt zones might even hook up into a larger reservoir. But spoiler: no scientist anywhere is claiming that’s on tomorrow’s chore list.

Which brings us to the great, headline-grabbing “16% chance (one in six) of apocalypse by 2100” further down in the popular reports — a number that, if ever printed on a lottery ticket, would bankrupt Las Vegas. From the article:

Still, climatologist Markus Stoffel and affiliated risk researchers estimate a ~16% probability of a VEI 7 or higher eruption occurring globally before the year 2100.

Except that particular prediction is not referred to by the scientists of the actual Yellowstone study, and has nothing to do with the Yellowstone study.

It comes from a some gentleman yclept Markus Stoffel. And he’s not even talking about Yellowstone. He’s talking about the entire planet. Nothing to do with Yellowstone.

And who is Markus when he’s at home? Is he a member of the team of authors of the Yellowstone study?

Nope.

Well, is he a vulcanologist?

Nope again.

He’s a climate professor at the University of Geneva. He’s published a lot, almost entirely regarding the effects of “climate change” on glaciers, mountain landslides, and mountain lakes.