The French, I think, must be world champions in the production of books lamenting the state of their economy (they are also good at taking antidepressants). Occasionally, it is true, someone writes a book to the effect that things are not so very bad in France, in fact that they are really quite good, at least by comparison with everywhere else; but this is so contrary to the majority of what is written that it has the quality of whistling in the wind. If the French economy had grown at the rate at which books are published predicting its imminent collapse, it would be flourishing indeed.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Beneath Paris”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-01-07.

May 5, 2019

QotD: A growing French industry

April 29, 2019

QotD: Prostitution

I had a few patients who were prostitutes. I remember one well-dressed lady in her 40s, whose profession I asked in the course of my history-taking.

“Dominatrix,” she said.

She was obviously very good at it because she had an international clientele, including, for example, a judge in Alabama. She told me that she never went anywhere in her car without her kit, for she might receive an emergency call at any time from Hong Kong or South Africa. You might have thought that being whipped by one woman in black fishnet stockings was as good as being whipped by another, but apparently this was (and I presume still is) not so: It’s the words and gestures that go with the whipping that count as well.

This activity of hers gave her a very good living (her car was far better than mine); she was sending her daughter to private school. I admired her enterprise and thought of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Was she or the judge in Alabama to blame? Was either of them to blame at all?

Of course, she wasn’t typical of the profession, and hard cases, as they say, make bad law. But I am not at all sure that I saw the poor prostitutes in my street as merely victims, as the new French law would have them. Not everyone with their life history becomes a crack-taking prostitute. This does not mean that I did not pity them for what they had become. If we can truly sympathize only with those who have done nothing to contribute to their own fate, we shall have very restricted sympathies indeed.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Turning Tricks Into Sympathy”, Taki’s Magazine, 2016-04-09.

April 17, 2019

Theresa May has been brilliantly successful in achieving her (true) aims

Theodore Dalrymple admits having misjudged Mrs. May as a failure, when in fact her plans have been coming brilliantly to fruition:

Like almost everyone else, I regarded [Theresa May] as a pygmy in courage and a giant in incompetence, but it is time for a re-assessment, especially with regard to her efforts to Britain’s exit from the European Union. After the Union granted a further delay to Britain’s departure, the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, said that it was his secret dream to prevent Britain from leaving. It is pleasing to know that Mr Tusk’s secret dreams so entirely coincide with those of the British political class, including (I surmise) those of Mrs May. At last we have a basis for full and final agreement.

Like the great majority of the British political class, Mrs May was always in favour of remaining in the Union. This class was so confident of its ability to persuade the population that it was right that it agreed with practically no demur to a referendum which would pronounce the winner as the side which obtained 50 per cent plus one of the votes cast. Thus the matter of British membership, it thought, would be settled once and for all.

The problem for the political class was now to find a method of overriding the result of the referendum without doing so in too blatant a fashion. And here, in Mrs May, it found a perfect leader.

Needless to say, Mrs May, having been selected as Prime Minister, could not just put forward her conviction that Britain should remain in the Union and say outright that she had no intention of carrying out the will of the majority. At that stage, such a disavowal of the result would have been politically impossible and might even have caused unrest. Instead, she went through a brilliantly elaborate charade of negotiating withdrawal, in such a way that the result would not be accepted by Parliament. Her agreement would be withdrawal without withdrawal, the worst of all possible outcomes, all complication and difficulty, and no benefit.

She knew perfectly well that the European Union, having drafted this agreement unacceptable to Parliament, would not renegotiate it. Why should it, since it knew that Parliament had no intention of demanding a real and total withdrawal, since it did not want to withdraw at all? She also knew that Parliament would never agree to a withdrawal without an agreement with the Union, as Parliament has repeatedly made clear.

April 10, 2019

Theodore Dalrymple on obesity

His latest in the New English Review:

It hardly requires me to point out that obesity has become a greater threat to the health of the human population in most parts of the world than famine. There was a wonderful cartoon recently in the British magazine, The Oldie, which captured this perfectly. A mother is taking a plate of food away from her child, who is protesting. “Think of the obese millions!” she says to him. When I was young, of course, we were told to finish what was on our plate and to think of the starving millions. Being a precocious little brat, I used to ask how eating what I did not want would help them. Let us just say that the reply was seldom well-reasoned, either in form or content.

It has now become an almost unassailable orthodoxy, at least in medical journals, that obesity is an illness in and of itself: that is to say, it does not merely have medical consequences, but — even without those consequences — is a disease. To be fat is, ipso facto, to be ill, in the same sense as to have Parkinson’s disease is to be ill.

Nor, according to the modern orthodoxy, is obesity to be considered the natural consequence of bad or foolish individual choices, a lack of self-control. That would be to blame the victim. The fat person is in effect the vector of forces that play upon him or her, without any contribution on his or her part.

This is an idea of long gestation. Reading an old text on obesity, published in 1975, and edited by one of my medical mentors, I came across the following quote from a paper written in 1962:

I wish to propose that obesity is an inherited disorder and due to a genetically determined defect in an enzyme: in other words that people who are fat are born fat, and nothing much can be done about it.

This is like saying that addicted people are born to be addicted, and until doctors discover a technical means of stopping their addiction, they might as well make no efforts on their own behalf. No doubt the people who adhere to this view – that obesity and addiction are illnesses simpliciter – think they are being generous but in fact they are forging psychological manacles. No doubt the fat woman in the bakery was at some level trying to prove to herself that obesity was a fatality and not under any possible individual control.

But is the theory in accord with the scene I have described above? In fact, the scene might lead us to a more nuanced or less categorical view of the problem of obesity (and, by extension, of other social problems) than we might at first adopt.

April 5, 2019

The Brexit trainwreck is “revealing to the British public the extent of its political class’s incompetence”

Theodore Dalrymple in City Journal on the scale of political tomfoolery going on in the Brexit clusterfutz:

The imbroglio over Brexit has at least had the merit of revealing to the British public the extent of its political class’s incompetence. If it is accepted that people get the leadership that they deserve, however, thoughts unflattering to self-esteem ought to occur to the British population.

Theresa May did not emerge from a social vacuum. She is typical of the class that has gradually attained power in Britain, from the lowest levels of the administration to the highest: unoriginal, vacillating, humorless, prey to the latest bad ideas, intellectually mediocre, believing in nothing very much, mistaking obstinacy for strength, timid but nevertheless avid for power. Thousands of minor Mays populate our institutions, as thousands of minor Blairs did before them.

Avidity for power is not the same as leadership, and Brexit required leadership. There was none to be had, however, from the political class. From the very first, it overwhelmingly opposed Brexit — for some, the eventual prospect of a tax-free, expense-jewelled job in Brussels was deeply alluring — but found itself in a dilemma, since it could not openly deny the majority’s expressed wish. Many Members of Parliament sat for constituencies in which a solid majority had voted for Brexit. They feared that they would not win their next election.

The opposition Labour Party was as divided as the Conservatives. Irrespective of what its MPs actually believed about Brexit—its leader was, until recently, ardent for leaving the European Union, which he believed to be a capitalists’ club, changing his mind for reasons that he has so far not condescended to disclose — its main concern was to force an election that it believed it could win, a victory that would soon make Brexit seem like a minor episode on the road to ruin. The majority of the Labour MPs wanted first to bring about the downfall of a Conservative government and second to prevent Britain leaving the European Union without an agreement — what might be called the leaving-the-Union-without-leaving option. But they wanted the first more than they wanted the second, so under no circumstances could they accede to anything that Prime Minister May negotiated. Because of her tiny majority in Parliament, the hard-line Brexit members on her own side who want Britain to leave without a deal, and the refusal of her coalition partner, the Democratic Unionist Party, to back her, May needs the support of a considerable proportion of Labour MPs — which, so far, she has not received.

But the House of Commons as a whole, including the Conservatives, deprived May of leverage with which to renegotiate, because it voted that it would not accept leaving the Union without a deal. This deprived the European Union of any reason to renegotiate anything: it was a preemptive surrender to the demands of the E.U. that makes Neville Chamberlain look like a hard-bitten poker champion.

April 2, 2019

QotD: The legacy of the soixante-huitards

It is one of the theses of this lucid book that the generation of May 1968 — or at any rate its leaders — has arranged things pretty well for itself, though disastrously for everyone else. If it has not been outright hypocritical, it has at least been superbly opportunist. First it bought property and accumulated other assets while inflation raged, paying back its debts at a fraction of their original value with depreciated money; then, having got its hands on the assets, it arranged for an economic policy of low inflation except in the value of its own assets. Moreover, it also arranged the best possible conditions for its retirement, in many cases unfunded by investment and paid for by those unfortunate enough to have come after them. They will have to work much longer, and if ever they reach the age of retirement, which might recede before them like a mirage in the desert, it will be under conditions much less generous than those enjoyed by current retirees.

It matters little whether this was all part of a preconceived plan or things just fell out this way, for that is how things now are. The result is that what was always a class society is in the process of becoming a caste society, in which only children of the already well-off have a hope of owning their own house.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Beneath Paris”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-01-07.

March 23, 2019

QotD: Pity the poor politicians

The first reason to pity them, however, is that someone, or rather some group of people, has to do politics, just as people have to do other unpleasant jobs, such as cleaning lavatories. If it were not for the politicians whom we actually have, there would only be others, not necessarily better. Politicians are like the poor: You have them with you always — except in Switzerland, that happy land where people do not even know who their president is, he being so profoundly unimportant.

But the second and more compelling reason to pity the poor politicians is that theirs is a dreadful life judged by normal standards. If it has its compensations, such as power, money, and bodyguards, they are bought at a dreadful cost. The other day I caught a glimpse of what that life must be like.

A television crew came to make a documentary about me. It will last about 45 minutes, will be watched (thank goodness) by only a small audience, and took two and a half days’ filming to make. The television crew was very nice, which is not my universal experience of television people, to put it mildly; but even so, two and a half days being followed by a camera is more than enough to last me the rest of my life.

I found the strain of it considerable, even though, really, nothing was at stake. It did not matter in the slightest, not even to me, if I made a fool of myself by what I said. There would be no consequences for my career, such as it is (it is almost over); there would be no humiliating exposures of my fatuity in the press, no nasty political cartoons as a consequence, and no insulting messages over the antisocial media. The television team was clearly not out to trip me up or perform a hatchet job on me. It was friendly and I could trust it not to distort what I said by crafty editing. But all the same, the attempt to act naturally while in the constant presence of a camera and a microphone with a furry cover was tiring. The order to be natural is a contradiction in terms. You might as well order someone to be happy.

Of course, one grows accustomed to anything in time. Just as a bad smell disappears from one’s awareness if one remains for long enough in its presence, so eventually one forgets about the presence of a camera and a microphone. No doubt politicians who live half their waking time within the field of these instruments learn to ignore their physical intrusiveness; but, of course, much more is at stake for them than it ever was for me. They are under constant surveillance; and just as the pedant reading a book pounces upon an error, even if it be only typographical, and marks it with his pen, so journalists and political enemies pounce upon a gaffe uttered by a politician and try to ruin him with it. And the more subjects come under the purview of political correctness, the easier it becomes to make a gaffe that will offend some considerable part of the eggshell population. In fact, much of that population actually wants to be offended; being offended is the new cogito that guarantees the sum. I am offended, therefore I am.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Pity the Poor Politicians”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-04-01.

March 21, 2019

Theodore Dalrymple reviews a new Jeremy Corbyn biography

It certainly doesn’t paint a pleasant picture of the man:

Jeremy Corbyn, Leader of the Labour Party speaking at a Rally in Hayfield, Peak District, UK on 25th July 2018 in support of Ruth George MP.

Photo by Sophie Brown via Wikimedia Commons.

In normal circumstances, no one would dream of writing a biography of so dreary a man as Jeremy Corbyn; but political correctness has so eviscerated the exercise of wit that dreariness is no obstacle to political advancement and may even be of advantage to it. The dreary, alas, are inheriting the earth.

Tom Bower is a biographer of eminent living persons whose books tend to emphasise the discreditable — of which he usually finds more than enough to satisfy most people’s taste for salacity. His books are not well-written but they are readable; one sometimes dislikes oneself for enjoying them. So Bower’s latest book Dangerous Hero: Corbyn’s Ruthless Plot for Power, is a bit of a surprise.

Jeremy Corbyn is not a natural subject for Bower because he, Corbyn, is not at all flamboyant and has even managed to make his private life, which has been far from straightforward, uninteresting. Corbyn, indeed, could make murder dull; his voice is flat and his diction poor, he possesses no eloquence, he dresses badly, he has no wit or even humour, he cannot think on his feet, and in general has negative charisma. His main assets are his tolerable good looks, attractiveness to women, and an ability to hold his temper, though he seems to be growing somewhat more irritable with age.

Bower has written a book that is very much a case for the prosecution. If he has discovered in Corbyn no great propensity to vice as it is normally understood, neither has he discovered any great propensity to virtue as it is normally understood, for example personal kindness. His concern for others has a strongly, even chillingly abstract or ideological flavour to it; he is the Mrs. Jellyby de nos jours, but with the granite hardness of the ideologue added to Mrs. Jellyby’s insouciance and incompetence.

[…]

His probity, cruelty or stupidity, might appeal to monomaniacs, but it presages terrible suffering for millions if ever he were to achieve real power: for no merely empirical evidence, no quantity of suffering, would ever be able to persuade him that a policy was wrong or misguided if it were in accord with his abstract principle. This explains his continued loyalty to the memory of Hugo Chavez and to his successor. What happens to Venezuelans in practice is of no interest to him whatsoever, any more than the fate of Mrs. Jellyby’s children were of no interest to her. For Corbyn, the purity of his ideals are all-in-all and their consequences of no consequence.

From a relatively privileged background, he formed his opinions early and has never allowed any personal experience or historical reading to affect them. On any case, according to Bower, he reads not at all: in this respect, he is a kind of Trump of the left. He has remained what he was from an early age, a late 1960s and 70s student radical of the third rank.

His outlook on life is narrow, joyless and dreary. He is the kind of man who looks at beauty and sees injustice. He has no interests other than politics: not in art, literature, science, music, the theatre, cinema — not even in food or drink. For him, indeed, food is but fuel: the fuel necessary to keep him going while he endlessly attends Cuban, Venezuelan, or Palestinian solidarity meetings. He is one of those who thinks that, because he is virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale.

March 1, 2019

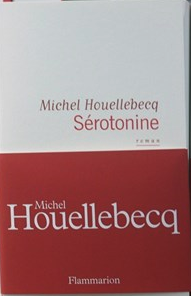

Theodore Dalrymple on Michel Houellebecq: “Houellebecq runs an abattoir for sacred cows”

At the New English Review:

Not reading many contemporary French novels, I am not entitled to say that Michel Houellebecq is the most interesting French novelist writing today, but he is certainly very brilliant, if in a somewhat limited way. His beam is narrow but very penetrating, like that of a laser, and his theme an important, indeed a vital one: namely the vacuity of modern life in the West, its lack of transcendence, lived as it is increasingly without religious or political belief, without a worthwhile creative culture, often without deep personal attachments, and without even a struggle for survival. Into what Salman Rushdie (a much lesser writer than Houellebecq) called “a God-shaped hole” has rushed the search for sensual pleasure which, however, no more than distracts for a short while.

Something more is needed, but Western man — at least Western man at a certain level of education, intelligence and material ease — has not found it. Houellebecq’s underlying nihilism implies that it is not there to be found. The result of this lack of transcendent purpose is self-destruction not merely on a personal, but on a population, scale. Technical sophistication has been accompanied, or so it often seems, by mass incompetence in the art of living. Houellebecq is the prophet, the chronicler, of this incompetence.Even the ironic title of his latest novel, Sérotonine, is testimony to the brilliance of his diagnostic powers and his capacity to capture in a single word the civilizational malaise which is his unique subject. Serotonin, as by now every self-obsessed member of the middle classes must know, is a chemical in the brain that acts as a neurotransmitter to which is ascribed powers formerly ascribed to the Holy Ghost. All forms of undesired conduct or feeling are caused by a deficit or surplus or malalignment of this chemical, so that in essence all human problems become ones of neurochemistry.

On this view, unhappiness is a technical problem for the doctor to solve rather than a cause for reflection and perhaps even for adjustment to the way one lives. I don’t know whether in France the word malheureux has been almost completely replaced by the word déprimée, but in English unhappy has almost been replaced by depressed. In my last years of medical practice, I must have encountered hundreds, perhaps thousands, of depressed people, or those who called themselves such, but the only unhappy person I met was a prisoner who wanted to be moved to another prison, no doubt for reasons of safety.

Houellebecq’s one-word title captures this phenomenon (a semantic shift as a handmaiden to medicalisation) with a concision rarely equalled. And indeed, he has remarkably sensitive antennae to the zeitgeist in general, though it must be admitted that he is most sensitive to those aspects of it that are absurd, unpleasant, or dispiriting rather than to any that are positive.

February 19, 2019

QotD: Internal contradictions of political correctness

… there was an article in the magazine arguing, on what might loosely be called philosophical grounds, for an end to the separation of men and women in sports. Women tennis players, for example, should compete against men, even if this means (as it does) that no woman could ever again make a living as a tennis player. In the name of equality of the sexes, one sex should be eliminated from a whole field of endeavor. Presumably, also, there should be no concessions for the handicapped, who would be forced to compete not against those similarly handicapped but against the fully fit.

Though this be madness, yet there is method in it: For the greater political correctness’ violation of common sense, the better — at least if its goal is power over men’s minds and conduct. In this sense it is like Communist propaganda of old: The greater the disparity between the claims of that propaganda and the everyday experience of those at whom it was directed, the greater the humiliation suffered by the latter, especially when they were obliged to repeat it, thus destroying their ability to resist, even in the secret corners of their heart. That is why the politically correct insist that everyone uses their language: Unlike what the press is supposed to do, the politically correct speak power to truth.

One of the strange things about the politically correct is that they never seem to become bored with their own thoughts. And this leads to a dilemma for those who oppose political correctness, for to be constantly arguing against bores is to become a bore oneself. On the other hand, not to argue against them is to let them win by default. To argue against rubbish is to immerse oneself in rubbish; not to argue against rubbish is to allow it to triumph. All that is necessary for humbug to triumph is for honest men to say nothing.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Two Forms of Mass Hysteria”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-03-11.

January 4, 2019

QotD: The modern C.V.

Take that ghastly soul-destroying document, the curriculum vitae. It is as inherently inflationary as clipping the coinage or fiat money. A friend of mine, whom I knew to be competent and conscientious, consistently failed to be appointed to positions for which he was eminently qualified. My wife, who knew the ways of modern appointment committees, asked to see the curriculum vitae he was supplying with his applications for the jobs.

She was horrified: He would never get a job with such a curriculum, it was far too old-fashioned. It gave merely his formal qualifications and the positions he had previously held, with references. No, no, said my wife to him, what you need is to boast. You have to make out that your piddling research might be chosen very soon for a Nobel Prize, that your occasional good deeds were as at great a personal sacrifice as those of Mother Teresa, and that you are a person whose outside interests are carried out at levels equal to the professional; in other words that you are multitalented, multivalent, and quite out of the ordinary. Moreover, your ambition must be to save the world, to be a pioneer and a path-breaker, not merely to do your best in the circumstances. You must be grandiose, not modest.

Of course, every other applicant would be similarly boastful, and so, like star architects trying to outdo each other in the outlandish nature of their buildings, my friend’s boasts had to be preposterous, quite out of keeping with his admirable character. But once he had swallowed the bitter pill of realism, he was appointed at once. We all have to be Barons Munchausen now.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Merits of Nepotism and Boasting”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-12-08.

December 26, 2018

QotD: Solipsistic self-esteem

Once you even begin to consider the question of your self-esteem, you are a lost soul; you have entered a Hampton Court maze of self-absorption, with very little chance of emergence from it, and with no hope of learning anything useful from it. To change the metaphor, the search for self-esteem is a swamp, a quicksand; or to change it yet again, it is to the soul what Émile Coué’s method, with its mantra that every day in every way you were getting better and better, was to the body. Every day, in every way, I am growing more and more conceited.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lose Yourself”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-11-10.

December 1, 2018

QotD: Toxic self-esteem

For a number of years I have been fighting a lonely one-man (or should I say one-person?) battle against self-esteem — not my own, of course, because I have just the right amount, but as the master key to human happiness.

Of the many possible human qualities, self-esteem, far from being desirable, is one of the most odious. It is much more closely related to conceit and self-importance than it is to self-respect or even self-confidence. People who talk of self-esteem do so as if it were an inalienable human right rather than something to be earned. In other words, self-esteem is like a fair trial: It doesn’t matter what you are like or what you have done, you have a right to it, at all times and in all places.

Of course, people who speak of lack of self-esteem know in their hearts that they are talking bilge. Sometimes patients would come to me and tell me that they had low self-esteem and I would tell them that at least they had one thing right. Instead of growing angry, as perhaps you might have expected, they would laugh, as if they had been caught out in an outrageous prank — which in a sense they had. As old-fashioned burglars in England used to say when caught red-handed by a policeman, “It’s a fair cop, guv.”

“Suppose,” I would ask, “someone told you that he had allowed his children to starve to death because he preferred taking crack to feeding them and that he had stolen all his aged mother’s savings, but that at least he had no problems with his self-esteem, what would you say?”

In fact, this was only just a rhetorical question because I had met many such persons, bursting with self-esteem and quite without any discernible virtues. Indeed, one of the sources of their bad character may have been their self-esteem, insofar as nothing could dent it, not even the hatred or contempt of everyone around them. If I were younger and more energetic, I would found a Society for the Prevention and Suppression of Self-Esteem.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lose Yourself”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-11-10.

November 16, 2018

QotD: Defining hate speech

Then, of course, there is the question of where hate-speech ends and legitimate commentary starts. It is generally easy to recognise the vilest abuse that is intended only to inflame and not to argue, just as it is easy to recognise pure pornography (I use the word ‘pure’ in its chemical, not its moral sense, of course). But often matters are much more complex than this.

For example, I recently saw the following statistic in a serious article on the internet: that Nigerian immigrants to Switzerland are seven times as likely to be convicted for a crime as Swiss citizens. Surely no one who wrote such a thing could think that it was calculated to create warm feelings in the hearts of the Swiss towards Nigerian immigrants, except those very few of Fabian mentality, who see in serial killers a cry for help (from the killers, of course, not from their victims).

The statistic – let us assume – is true. But then let us ask whether it has been corrected for the different sex and age structures of the two populations, that of the Nigerian immigrants and that of the Swiss population.

If it has not (and the article does not say), it is easily conceivable that a better, or at least different, statistic would be that Nigerian immigrants are only twice or three times as likely to be convicted for a crime as Swiss citizens. And if this were in fact the case, would the man who published the article be guilty of hate-speech, or merely of intellectual error? Is the test of hate-speech to be whether something does in fact bring a group into hatred, ridicule and contempt, or whether it is intended to do so?

It is easy to multiply examples. In this country, young Moslem men far out-fill their quota in prison, while young Hindu and Sikh far underperform where criminal conviction is concerned. Is this an interesting and important sociological fact, or an incitement to hatred, ridicule and contempt, or perhaps both?

A further problem is that of judging how sensitive people actually are or should be to perceived slights and insults. Just as the expression of hatred can be self-reinforcing, so can the sensitivity to slight and injury. The more you are protected from it, the more of it you perceive, until you end up being a psychological egg-shell. The demand for protection becomes self-reinforcing, until a state is reached in which nobody says what he means, and everybody infers what is not meant. Temperatures, or tempers, are raised, not lowered. The disgracefully pusillanimous (and incompetent) Macpherson report into the killing of Stephen Lawrence demonstrated the risks we run: it suggested that a racial incident should be defined as an incident which any witness to it believed to be racial, without there being any need for objective evidence that it was. Where a British judge can be so pusillanimously unattached to the rule of law, we can be sure that one day hate-speech will be defined as any speech that anyone finds hateful.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Hating the Truth”, Salisbury Review, 2011-06.

November 6, 2018

QotD: Architectural modernism

In this scholarly, learned but also enjoyably polemical book, Professor Curl recounts both the history and devastating effects of architectural modernism. In no field of human endeavour has the idea that history imposes a way to create been more destructive, or more importantly destructive: for while we can take avoiding action against bad art or literature, we cannot avoid the scouring of our eyes by bad architecture. It is imposed on us willy-nilly and we are impotent in the face of it. Modern capitalism, it has been said, progresses by creative destruction; modern architecture imposes itself by destructive creation.

As Professor Curl makes clear, the holy trinity of architectural modernism — Gropius, Mies and Corbusier — were human beings so flawed that between them they were an encyclopaedia of human vice. They spoke of morality and behaved like whores; they talked of the masses and were utter egotists; they claimed to be principled and were without scruple, either moral, intellectual, aesthetic or financial. Their two undoubted talents were those of self-promotion and survival, combined with an overweening thirst for power.

Their intellectual dishonesty was startling and would have been laughable had it not been more destructive than the Luftwaffe. When they claimed to have no style because their designs were imposed on them by history, technology, social necessity, functionality, economy etc., and like Luther proclaimed they could do no other (which soon became the demand that others could do no other also), they remind me of the logical positivists who claimed to have no metaphysic. But if no given style or metaphysic is beyond the choice of he who has it, to possess a style or a metaphysic is inescapable in the activity of artistic creation or thought itself. And even my handwriting has a style, albeit a bad one.

In like fashion, as this book makes beautifully clear, the modernists were adept at claiming both that their architecture was a logical development to and aesthetic successor of classical Greek architecture and utterly new and unprecedented. The latter, of course, was nearer the mark: they created buildings that, not only in theory but in actual practice, were incompatible with all that had gone before, and intentionally so. Any single one of their buildings could, and often did, lay waste a townscape, with devastating consequences. What had previously been a source of pride for inhabitants became a source of impotent despair. Corbusier’s books are littered with references to the Parthenon and other great monuments of architectural genius: but how anybody can see anything in common between the Parthenon and the Unité d’habitation (an appellation that surely by itself ought to tell us everything we need to know about Corbusier), other than that both are the product of human labour, defeats me.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.