Chris Selley makes the case that this year’s federal election is the worst of all:

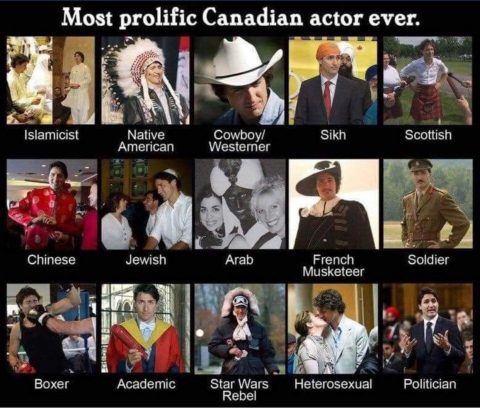

It has been widely suggested that this might be Canada’s Worst Election. Certainly it is dreary as all get-out. We began with interminable back-and-forth about abortion, which all party leaders pledge to do absolutely nothing about. If one or more of them are lying, it seems very unlikely they would admit to it at a press conference. The next mania was over Justin Trudeau’s blackface revues, which were radioactively damaging to whatever was left of his Most Enlightened Gentleman brand, but which mostly served as an opportunity for exhibitionist partisan insanity and cringeworthy journalism.

[…]

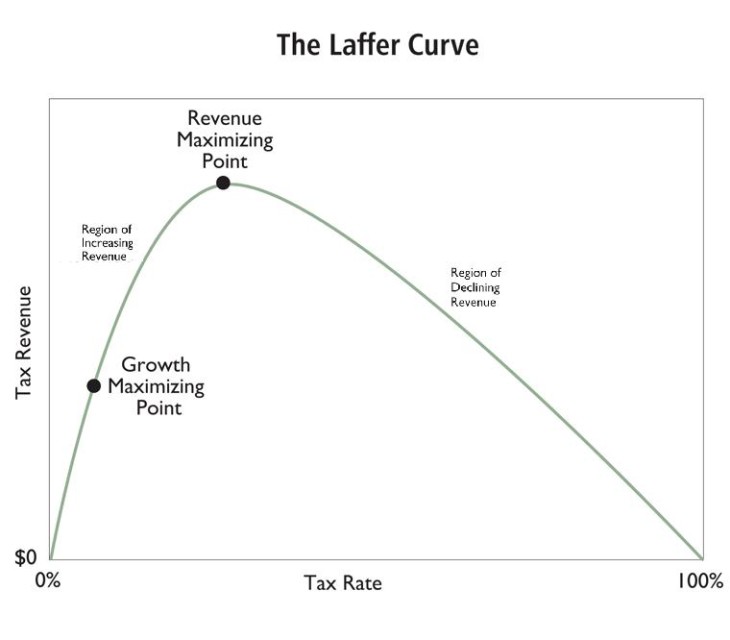

By rights the Conservatives should be mopping the floor. But they can hardly attack Trudeau’s social-engineer budgeting when they’re relaunching their flotilla of boutique tax credits for kids’ sports and arts programs and public transit. Why not just make their tax cut even bigger and let people spend their money how they please?

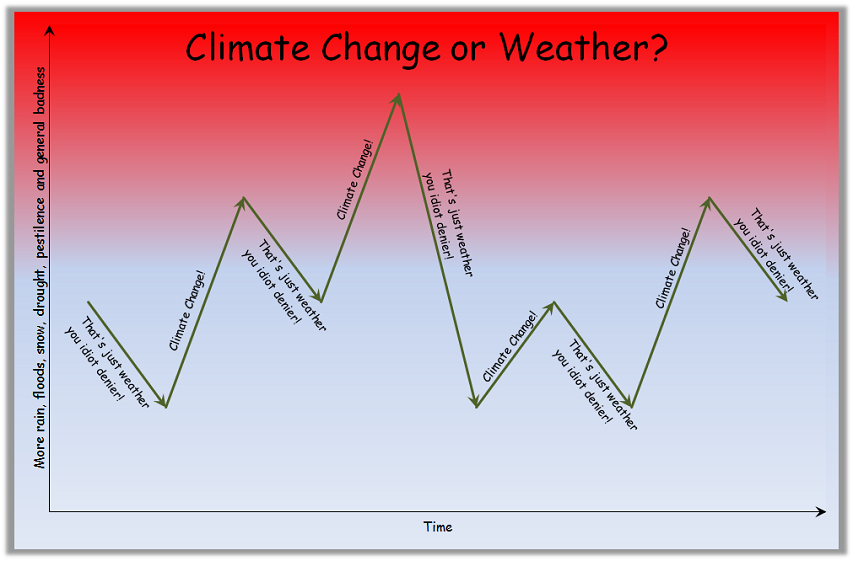

Similarly, the Conservatives would be on much firmer ground criticizing Trudeau’s housing-market interventions if they weren’t promising to review the mortgage stress test and bring back 30-year mortgages — something Stephen Harper’s government eliminated in 2012. Having decided carbon pricing was evil almost entirely because Justin Trudeau supports it, the Tories still struggle to defend any effective or efficient policy against climate change.

Any hope that Maxime Bernier might hold Scheer’s feet to the fire on free minds and free markets went up in flames ages ago as his People’s Party attracted far more authoritarian/nativist refugees from the Conservative Party of Canada than libertarian ones. Jagmeet Singh is bargaining hard to sell the NDP’s credibility down the river to appease all-but-totally uninterested Quebec nationalists — shamefully promising not to intervene against Bill 21, as if he would ever get the chance. Elizabeth May and her Green Party constantly remind us that they’re really quite odd: May insisting Longueuil candidate Pierre Nantel isn’t a separatist while Nantel shouts “I’m a separatist!” through a bullhorn is the weirdest thing she has done since the last weird thing.

The debates have worked out as badly as conceivably possible: The Leaders’ Debate Commission, created by the Liberals to solve a problem that didn’t exist — aieeee! Too many debates! — has reinvented the wheel, crushing both Maclean’s debate (which Trudeau declined to attend) and the Munk debate on foreign affairs (which has been cancelled due to Trudeau’s lack of interest) beneath it.