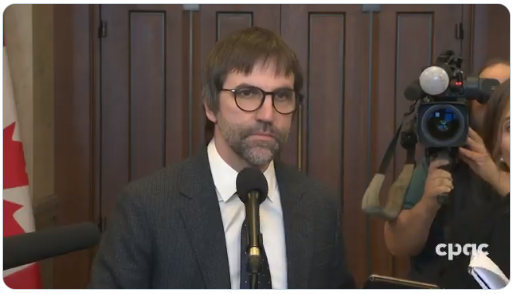

Michael Geist on the bull-headed determination of the Canadian federal government — and specifically Heritage Minister Steven Guilbeault — to “solve” a problem by introducing savagely anti-consumer internet regulations:

The harm that will come from these policy choices is difficult to overstate. By focusing the tax burden on sales taxes rather than technology company revenues, consumer costs will go up and the company profits will be left untouched. The CRTC powers will lead to years of hearings and follow-on litigation, yielding few tangible benefits for creators. The mandated Cancon contributions will spark trade wars and make Canada a less attractive market for new services leading to fewer choices and less competition, while the link licensing requirement will result in blocked sharing of news articles on social media sites that hurts both Canadians and media organizations. All the while, the issues that really matter – privacy, anti-competitive behaviour, online hate, misinformation, a fair share of tech corporate profits – are left largely untouched.

How did the government end up with the worst of all worlds on Internet regulation?

The starting point was the 2015 election in which it committed to no new Netflix taxes (prompted by a Conservative pledge on the issue) and subsequent consultations on everything from copyright to digital cultural policy. The result was then-Heritage Minister Melanie Joly struggling to honour the no-tax commitment, while satisfying increasingly vocal demands from some stakeholders for one. Those calls increased after the results of her cultural policy consultation were released, which largely focused on a rejection of new Internet taxes and support for net neutrality.

In the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, worries about Russian election interference, and Christchurch massacre broadcast live online, the policy winds shifted and the government was clearly looking to become more active on the Internet regulation file. That led to Election Act provisions that were generally viewed as successful. It also paved the way for a 2019 election platform that was far aggressive on social media and the Internet, with commitments to address everything from privacy to hate speech online.

[…]

If the government were to address the real concerns, there would be long-overdue privacy reforms, a more aggressive approach on competition issues, measures to address online hate and misinformation, and pursuit of a global agreement on fair taxation of technology company revenues. If it wants to support increased film production from indigenous groups or help the news sector, it can make those policy choices and use general tax revenues without creating a massive regulatory infrastructure.

Instead, it is turning to the harmful policies noted above that raise consumer costs (digital sales taxes), regulate online Cancon with mandated spending requirements (even though the industry has record production led by Netflix), dispense with any pretense of maintaining net neutrality, lead to blocked sharing of news articles (mandated licence for social media sites merely for linking to news content), and result in services avoiding the Canadian market (market interference in payments from services such as Spotify). Much of this will be overseen by the newly empowered CRTC, leading to lengthy hearings that primarily benefit lawyers. After having badly mishandled Canadian digital policy, the government now seems content to take a pass on the important issues and leave the controversial non-issues to the regulator and the courts.