Tim Harford poses and answers some common questions about the much-talked-about 7-billionth birth:

There will be 7bn of us come Halloween? You’re kidding.

Someone at the UNPFA has a sense of humour, it seems. This is a terrifying prospect to some and cheery for others, while most of us find it irrelevant. Halloween seems appropriate.

This is a statistical projection, and statistical projections don’t have a sense of humour.

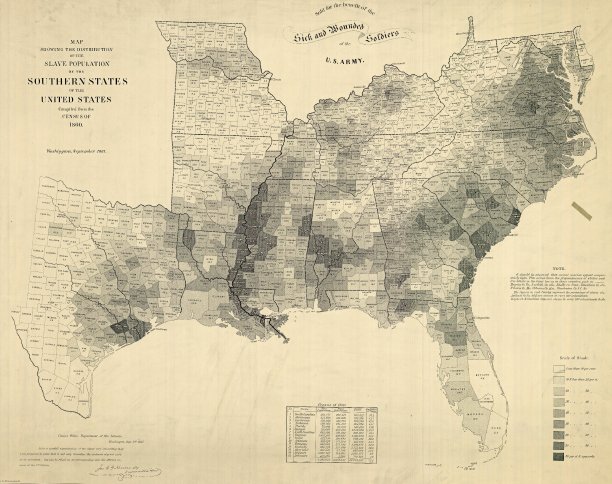

But they do have margins of error. The UNPFA doesn’t even know whether the seven billionth person will be born in 2011. Even the UK is currently relying on 10-year old census data. There are places in the world where the data are decades old and we’re just guessing at the population. Still, such celebrations — if they are celebrations — do pass the time.

[. . .]

So Malthus was wrong?

Even Robert Malthus realised that there was such a thing as birth control. His more excitable successors, such as Paul Ehrlich, author in 1968 of The Population Bomb, have been fairly thoroughly rebutted by subsequent events. Dan Gardner, author of the fascinating Future Babble, summarises Ehrlich’s three scenarios for the 1980s as “everybody dies” (starvation-triggered nuclear war), “every third human dies” (starvation-triggered virus) and in the optimistic scenario “a billion people still die of starvation”.

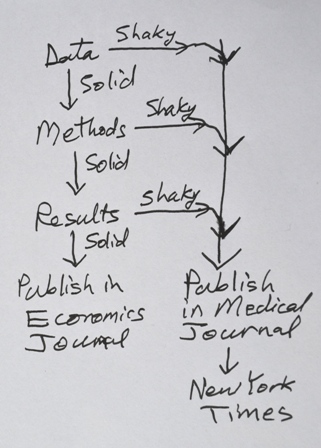

Aid Watch has complained before about shaky social science analysis or shaky numbers published in medical journals, which were then featured in major news stories. We questioned creative data on stillbirths, a study on health aid, and another on maternal mortality.

Aid Watch has complained before about shaky social science analysis or shaky numbers published in medical journals, which were then featured in major news stories. We questioned creative data on stillbirths, a study on health aid, and another on maternal mortality.