In the most recent Libertarian Enterprise, Sean Gabb discusses what British Conservatives have been warned against describing as “Cultural Marxism”:

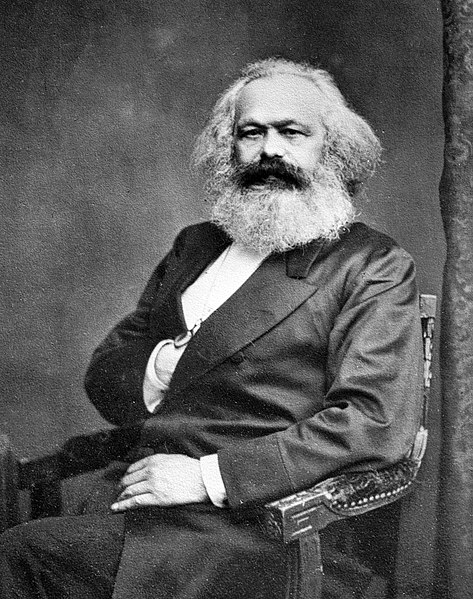

So far as I understand him — and I write as an outsider to any school of Marxist ideology — Marx made five essential points. First, there have been, since the French Revolution, two classes — the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Second, the bourgeoisie owns the means of production and exploits the proletariat through the extraction of surplus value. Third, this is an unstable parasitism, as the reinvestment of surplus value leads to periodic crises of over-production. Fourth, these crises concentrate wealth in fewer hands and expand and immiserise the proletariat. Fifth, there will be an inevitable revolution, in which the expropriators will be expropriated and a communist society will emerge. A further and perhaps optional sixth point is that the inevitable revolution can be hurried by the defection of informed bourgeois intellectuals to radicalise and form a vanguard for the proletariat.

Now, where is any of this in the present mix of climate alarmism and obsession with the alleged oppression of racial and sexual minorities? How is capitalism supposed to be overthrown by getting Sainsbury to fill its advertisements with pictures of black people eating Christmas dinner? Ditto boycotts of Israeli pharmaceuticals? Ditto arguing with or against radical feminists over the exact status of men who change sex?

The answer, of course, is the Cultural Marxist hypothesis — that the present culture wars are a product of the writings of Antonio Gramsci and the Frankfurt School. These men took the Marxian concept of “false consciousness” — that the bourgeoisie keeps the workers quiet by making them believe that all is for the best — and enlarged it into a project for achieving a counter-hegemony by taking over the means of cultural reproduction.

There is some truth in this answer, so far as these writings are prescribed in most university humanities departments, and many advocates of the new totalitarianism have at some time called themselves Marxists. It is, even, so a weak answer. Before about 60 AD, most Christians were Jews, and Christianity ever since has retained some Jewish religious writings among its core texts. But nothing is achieved by describing Christianity as “Gentile Judaism.” The differences between the two faiths are too essential to define either by reference to the other. In the same way, the present totalitarianism has nothing to do with the essential claims of Marxism. It lacks any interest in the analysis of surplus value, and its belief in the instability of unregulated markets derives mainly from a reading of Keynes and the welfare economists of the Cambridge School.

I prefer the term “cultural leftism.” I prefer this because the present totalitarianism is based on belief in an appearance of equality mediated by the State. It therefore has elements of socialism as reasonably defined. But it is in no sense Marxist. Its revealed preference is for a ruling class that is a coalition of politicians, administrators, policemen, lawyers, educators, plus media and business interests. So far as individuals move freely between them, these groups are mutually permeable. If they disagree over incidentals, they preside collectively over a mass of the ruled who are mostly well-nourished, but who are too atomised and intimidated by often meaningless words to combine in opposition.

Indeed, if I prefer my chosen term, I see little point in arguing against what it describes. Undoubtedly, this must be explained and opposed. But too much analysis of particulars can risk an overlooking of the much more important generality. This is that, in every time and place, there have been those who want to get on with their lives and those who want to control others. These latter will take up whatever body of ideas is most likely within the prevailing assumptions of their age to legitimise their urges.