The Great War

Published on 11 Jun 2018How SMS Goeben and SMS Breslau, two German warships in 1914 sailed under Ottoman flag and helped Enver Pasha to get the Ottoman Empire into World War 1.

June 12, 2018

The Goeben & The Breslau – Two German Ships Under Ottoman Flag I THE GREAT WAR On The Road

June 6, 2018

D-Day – I: The Great Crusade – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 6 Jun 2017D-Day: June 6, 1944, the day when Allied forces stormed the beaches of Normandy to retake France from the Germans. They hoped to take the Germans by surprise, and their decision to brave rough weather to make their landings certainly accomplished that, but despite these small advantages, the American forces at Utah and Omaha Beach had to overcome monumental challenges to establish a successful beachhead.

May 30, 2018

Decisive Weapons S02E04 – U-Boat Killer: The Anti-Submarine Warship

erana19

Published on 25 Jan 20161996-1997 BBC documentary series. Series 2, Episode 4.

May 26, 2018

Sir Humphrey debunks the notion of maintaining a “reserve fleet”

The US Navy keeps a lot of ships around after they’ve been retired from active service (sometimes for decades), and some in the UK are asking if the Royal Navy should do something like that with the soon-to-be-retired Type 23 frigates. Sir Humphrey explains in great detail why this shouldn’t happen:

HMS Westminster (foreground) and HMS Iron Duke, Type 23 frigates of the Royal Navy, in the naval base of Portsmouth, August, 2000.

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The subject of ‘Reserve Fleets’ is something that often comes up across the internet whenever naval forces are discussed. To many casual observers there is an innate draw to the idea of holding ships back as a contingency against a potential threat. No matter how appealing this idea seems on the surface though, there are a multitude of good reasons why keeping complex warships in reserve at the end of their life is usually a very bad idea.

In broad terms these reasons boil down to four key areas – Maintenance & Material and People & Training. Each of these areas poses a challenge which brought together makes it extremely difficult to consider keeping a ship credible once she has paid off.

Maintenance & Material

The Royal Navy has historically not maintained a large reserve fleet since the 1950s, when the combination of the loss of conscript manpower, the increasing complexity of warships adding to reactivation times and the reality that any global conflict would go nuclear quickly meant that reserve fleets were relatively worthless.After the late 1950s the RN maintained a ‘Standby Squadron’ that usually comprised several vessels that while not fully active, were kept in reasonable running order. For many years Chatham dockyard functioned as the home of the Squadron, which usually comprised ships drawn from classes still in service, that could be brought up to readiness quickly to replace other vessels at sea. This occurred during both the Cod War and the 1982 Falklands War.

It is not clear when the Standby Squadron was formally discontinued, but it played a key part in the RN force structure into the 1980s. For instance, the 1981 defence review foresaw a number of escorts (possibly 7-8 out of 50) being held in quasi-active status. The RN also maintained other ships in full reserve – such as during the lifetime of the Invincible class when usually one of the three was placed into reserve for a year or two ahead of deep refits.

The key distinction here is that this sort of set up required a heavy investment of resources and manpower to keep the ships maintained and fit for sea. A modern warship is never truly alone during her active life – there are always people onboard to maintain systems and keep watch over her. By contrast ships that decommission and pay off will progressively see less and less people onboard until one day they have been stripped down and become ‘dead ships’, and they will be left to rot until the scrappers take them.

To keep a ship in a salvageable condition, able to be made ready for sea requires a significant amount of maintenance and upkeep. This is something that is costly, requiring regular dockings, inspections and repairs, as well as the cost of keeping the ship preserved and vaguely usable. To put a ship into Reserve with the intention of using her again does not mean she can be forgotten about – quite the contrary, they require regular care and maintenance.

To put a ship into reserve at the end of her life and be certain of using her again would require an additional refit to rectify defects. It would also require regular inspections, support and attention throughout the period in reserve.

For a ship that is likely to be used again, it makes reasonable sense to do this as every pound spent on preventative maintenance is likely to save many more in reactivation costs. For a ship likely to pay off, this makes far less sense – you are spending a lot of money to park a ship and wait for it to be scrapped.

May 2, 2018

Uses and misuses of the Baltic Dry Index

At the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall explains why, for example, Zero Hedge‘s witterings about the changes in the Baltic Dry Index are not actually predictive of boom or bust in the global economy:

As background, the volume of such shipping – dry is referring to dry bulk cargoes, wheat, grains, cement, that is, not container stuff and not oils – is an important indicator of global growth. Trade tends to, tends to note, increase faster than growth itself. If the volume of trade falls off a cliff then we would indeed think that there’s going to be a kablooie in our global GDP figures.

The Baltic Dry is an index of the prices of shipping these cargoes. It’s thus the interaction of the supply of shipping as against the demand for it. That’s rather more than subtly different to the volume of world trade.

The basic background here is that there are reasonably long lead times to get more shipping afloat. And once it is afloat then it tends to stick around for a decade or two. Building the boat is a sunk cost (sorry) so you keep trying to use it as long as income from doing so is above marginal costs, of maintenance and fuel (and maintenance will be skipped in some circumstances) and bugger the mortgage. The supply of shipping is near entirely inelastic on an annual basis, near entirely elastic on a two decade basis.

Demand for shipping is much more elastic in that shorter term. As is usual when we’ve an inelastic supply meeting an elastic demand in a marketplace we get wild price swings. They being what causes that longer term elasticity – as with, say, oil from conventional reservoirs.

The Baltic Dry can drop because more ships are being launched, it can rise because more are scrapped. Not because – note the can here – the volume of trade has changed at all.

What has actually been happening in shipping in general is that the ship owners all looked at how trade was growing before 2008. So, they thought, aha! 5% volume growth! (Numbers here are made up but indicative of the major points) Let’s order more spanking new ships! Which then start arriving in 2010, 2011. Flooding the market with new supply. And shipping volume didn’t grow at 5%. It grew at 2% instead. (Again, these numbers are made up, reflecting memory and thus not accurate, but the relationships between them are about right) So, prices plunge.

But it’s those prices which plunge, not the volume of world trade.

April 13, 2018

India and the “Quad”

At Strategy Page, Austin Bay discusses India’s position, both geographically and militarily with respect to China:

As the Cold War faded, a cool aloofness continued to guide India’s defense and foreign policies. Indian military forces would occasionally exercise with Singaporean and Australian units — they’d been British colonies, too. Indian ultra-nationalists still rail about British colonialism, but the Aussies had fought shoulder to shoulder with Indians in North Africa, Italy, the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and suffered mistreatment by London toffs. Business deals with America and Japan? Sign the contracts. However, in defense agreements, New Delhi distanced itself from Washington and Tokyo.

The Nixon Administration’s decision to support Pakistan in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War [Wikipedia link] embittered India. Other issues hampered the U.S.-India relationship. Indian left-wing parties insisted their country was a “Third World leader” and America was hegemonic, et cetera.

However, in the last 12 to 15 years, India’s assessments of its security threats have changed demonstrably, and China’s expanding power and demonstrated willingness to use that power to acquire influence and territory are by far the biggest factors affecting India’s shift.

In 2007, The Quad (Quadrilateral Security Dialogue), at the behest of Japan, held its first informal meeting. The Quad’s membership roll sends a diplomatic message: Japan, Australia, America and India. Japan pointed out all four nations regarded China as disruptive actor in the Indo-Pacific; they had common interests. Delhi downplayed the meeting, attempting to avoid the appearance of actively “countering China.”

No more. The Quad nations now conduct naval exercises and sometimes include a quint, Singapore.

The 2016 Hague Arbitration Court decision provided the clearest indication of Chinese strategic belligerence. In 2012, Beijing claimed 85 percent of the South China Sea’s 3.5 million square kilometers. The Philippines went to court. The Hague tribunal, relying on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea treaty, supported the Filipino position that China had seized sea features and islets and stolen resources. Beijing ignored the verdict and still refuses to explain how its claims meet UNCLOS [Wikipedia link] requirements.

That is the maritime action. India and China also have mountain issues. In 1962, as the Cuban Missile Crisis diverted world attention, the two Asian giants fought the Indo-Chinese War [Wikipedia link] in the Himalayas. China won. The defeat still riles India.

April 3, 2018

The Neutral Ally – Norway in WW1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

The Great War

Published on 2 Apr 2018Norway declared neutrality when the First World War broke out and as a nation with a large merchant fleet, profited from the war economically.

March 26, 2018

The container revolution in shipping

Is there anything as ubiquitous as the humble shipping container these days? There’re used for all kinds of “second career” purposes, but it’s easy to miss just how important to the growth in international trade … and the rise in global wealth … those containers have been. Marc Scribner gives a quick shout-out to the container:

One of the most underappreciated drivers of the modern global economy is the humble shipping container. Widely adopted internationally in the second half of the 20th century, intermodal containers largely supplanted break bulk cargo — the bags, barrels, pallets, and crates that must be individually loaded and unloaded onto ships, railcars, and trucks.

Intermodal containers are standardized in size and design, allowing them to be stacked onto large container ships, which can transport thousands of containers. In port, containers can be lifted onto railcars and flatbed trucks, enabling quick access to inland distribution centers and manufacturing facilities.

Containerization dramatically reduced costs all around. Fewer dockworkers were needed to load and unload vessels and larger ships were built thanks to stackable containers. Fewer ports were needed to transport an increasing volume of goods and freight insurance rates fell due to their durability and securability.

These transportation cost declines due to containerization have been estimated to have increased the volume of world trade far more than the proliferation of free trade agreements since the end of World War II. This means, according to recent research published in the Journal of International Economics, that while trade policy was important (and CEI is a strong supporter of trade liberalization), technological change in the shipping industry was responsible for enabling more trade among countries than improvements in government policy. It is important to note that for global commerce going forward, however, government policy is likely to be more important as containers have already been widely adopted, particularly in wealthy industrialized countries.

March 14, 2018

The navy we need versus the navy we’re willing to pay for

Ted Campbell recounts the ups and downs of the federal government’s plans for the Royal Canadian Navy over the last few decades:

A Chilean navy boarding team fast-ropes onto the flight deck of RCN Halifax-class frigate HMCS Calgary (FFH 335) during multinational training exercise Fuerzas Aliadas PANAMAX 2009.

US Navy photo via Wikimedia.

One of my old friends, commenting to another equally old friend on social media, said this: “Surely, the PM and his government must see the obvious — that as the oceans warm and the ice melts the Northwest Passage becomes navigable year round. He’s been sounding off about climate change ad nauseum so that would seem to be understood by him. As a teacher he must also know that European colonial powers sought a shortcut between east and west but were deterred by ice. That’s changed, which he acknowledges, and Canada’s claim of the.increasingly ice free Northwest Passage as sovereign territory is under threat. Absent Canada’s willingness, and any capability, to enforce it’s claim, Canada surrenders any legitimate right to ownership of the Northwest Passage and the resources in the territory it abuts. That a maritime nation bordered by three oceans needs a blue-water navy is axiomatic. And once the PM acknowledges that the Northwest Passage is about to become Canada’s Suez Canal he must recognize that it, too, needs to be protected and defended by the Royal Canadian Navy. But the navy can only do that if it has ships and sailors. If Canada doesn’t expend the effort to protect its shores and assert its claims someone else will.” Sound pretty sensible, doesn’t it? Climate change will, very possibly, open the Northwest Passage; it Canada cannot patrol and police those waters then others will exploit them; it’s the Navy’s job to patrol and police our waters … I have argued that the “constabulary fleet” that should do that ought not to be in the Navy, but that’s a different issue … for now.

[…]

Way back when ~ I’m working from memory and I’m happy to have these numbers corrected ~ the Royal Canadian Navy said, in a document called “Leadmark,” if my memory serves, that, in addition to infrastructure (headquarters, schools, dockyards, etc) it needed:

- A fleet with global “reach” which meant more than a dozen “major combatants” (destroyers and frigates) plus four support ships so that, at any time, it could have one combat-ready task group in each of any two of the world’s oceans;

- A coastal (three coasts) patrol fleet consisting of a mix of submarines and another dozen “minor combatants” (corvettes and mine hunters);

- Organic air elements for those fleets;

- Auxiliary and training vessels.

Circumstances changed over time but the Paul Martin government finally committed to new helicopters for the fleet and thanks to his decision and to the perseverance of the Harper government they are, finally, entering service, only 25 years after Jean Chrétien abruptly cancelled the Mulroney government’s signed contracts for (then) new shipborne helicopters.

[…]

What we, Canadians, do not have is a properly funded plan to build the real Navy that the country with the world’s longest coastline, that borders three oceans, needs and deserves.

Since I am pretty sure that, absent some catastrophic events, Prime Minister Trudeau has no interest in warships (or the Coast Guard) I can be fairly confident that while new ships will be built they will be too few in number for the jobs that need doing.

There are no votes in promising to rebuild the military. The Liberals will ignore it and the Conservatives would be wise to not make it much of a campaign issue … Canadians, an overwhelming majority of Canadians just don’t care. But the Conservatives need to get some first rate naval and shipbuilding people into a room and decide, for themselves, what the real costs are for what the Royal Canadian Navy really needs.

The expected warming of the Arctic Ocean and the potential opening of new shipping lanes through areas currently claimed by Canada should be a huge encouragement for the federal government to get serious about ensuring that the RCN, the Canadian Coast Guard and the RCMP are properly prepared and equipped to protect our sovereignty in this region. As in so many other climate change matters, however, the government loves to talk the talk but is manifestly uninterested in walking the walk. More new ships, submarines, helicopters, bases, and the military staff to crew/staff them would be a very expensive commitment that wouldn’t shore up votes in those critical marginal constituencies and would reduce the government’s ability so spend money in aid of getting re-elected (the Liberals are in power now, but the same sort of political calculus applies to the Tories as well).

Mr. Campbell is a Conservative and clearly harbours hopes that Admiral Andrew Scheer will be more willing to make the RCN a priority, but history does not support that hope. The last time (and possibly only time outside periods of declared war) that a Canadian government was serious about the military was before 1957. Canadians are hopelessly in love with the idea of being a peaceful nation and have never been willing to engage with that old Latin tag “Si vis pacem, para bellum“

February 25, 2018

Amphibious Landing Craft – Widow Compensation – Repatriation I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 24 Feb 2018Ask your questions here: http://outofthetrenches.thegreatwar.tv

February 1, 2018

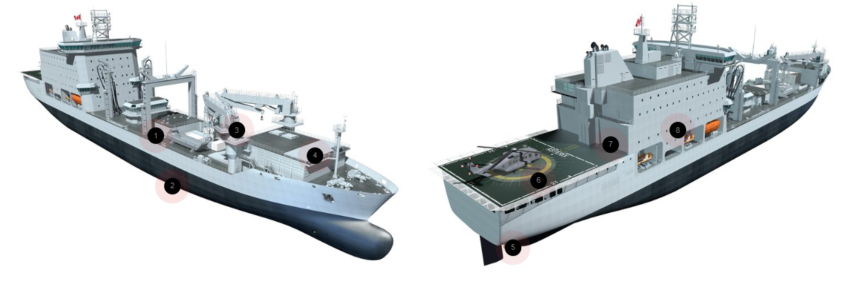

MV Asterix accepted by the Royal Canadian Navy

With the Queenston-class AOR ships still pinned to the drawing board, the Royal Canadian Navy has been reduced to borrowing support ships from allies and friendly nations to allow our combat ships to operate further from shore than a local fishing boat, the delivery and acceptance of the MV Asterix has to count as good news:

Davie Shipbuilding and Federal Fleet Services announced that following an intensive period of at-sea trials and testing, Asterix has been formally accepted by the Department of National Defence and has now entered full operational service with the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

As planned, Asterix performed daily replenishment-at-sea (RAS) exercises with the RCN and conducted extensive RCAF CH-148 Cyclone helicopter operations to prove and demonstrate the world-leading capabilities of the Resolve-Class Naval Support Ship. These exercises have included everything from dual RAS operations to helicopter landing, take-off and vertical replenishment trials.

Spencer Fraser, CEO of Federal Fleet Services commented “To deliver the first Canadian naval ship in over twenty years, the first supply ship in almost 50 years, and to reach FOC so efficiently and in such a short period of time is a testament to the hard work, dedication and dynamism of the teams at Davie and FFS. We are all very proud of our achievement and appreciative of the professional support we have received from DND and PSPC.”

Asterix has been leased by the government, and will be operated by a blend of merchant seamen and RCN/RCAF personnel as required for any given mission. She’ll remain an MV, not an HMCS and is not expected to be operated in “hot” environments where combat could occur. She will remain with the fleet at least until the planned-but-not-yet-started Queenston class ships are ready for service. Davie has offered to refit another ship for the RCN to lease (so we’d have one AOR for the East coast and one for the West), but so far the Trudeau government has resisted the offer.

January 30, 2018

Fitness tracker heat map shows dangerous activity near wrecked WW2 ammunition ship

The SS Richard Montgomery was a WW2 Liberty ship that ran aground near Sheerness in August 1944 carrying a cargo of bombs and other explosives. Part of the cargo was removed before the ship broke up and sank just offshore. There’s still quite a lot of TNT onboard the wreck, and it’s recently come to light that someone has been visiting the wreck, thanks to fitness tracker data:

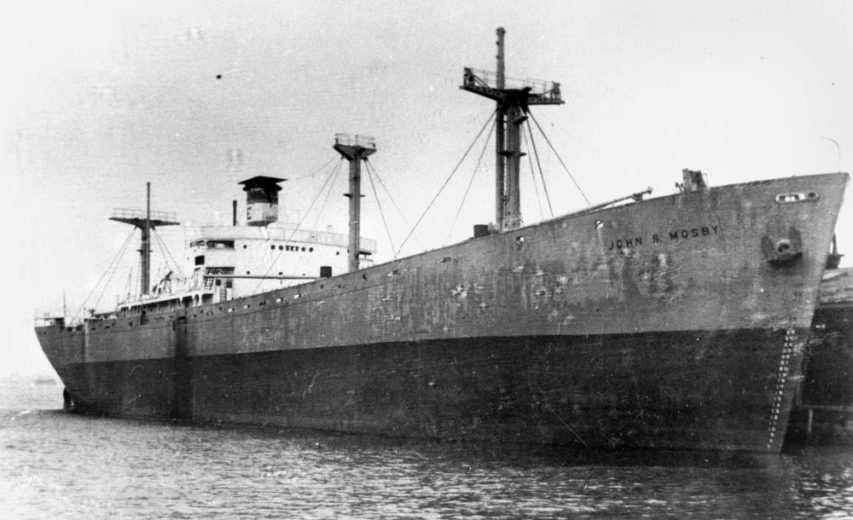

The SS John S. Mosby, a Liberty ship similar to the SS Richard Montgomery

Photo from the John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, via Wikimedia.

The information came to light after social media users realised that the latest version of Strava’s heat map, which shows the aggregated routes of all of its users, could be used to figure out where Western military bases in the Middle East are. Fitness-conscious soldiers, running around the bases’ perimeters, built up visible traces on the heat map over time.

However, of much more concern is the revelation that people have been poking around the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, a Second World War cargo ship that was carrying thousands of tonnes of explosive munitions from America to the UK. The ship grounded in the Thames Estuary, in England, in August 1944, barely two miles north of Sheerness.

Extract from Admiralty chart of Sheerness (Crown copyright):

The multicoloured box is the location of the SS Richard Montgomery wreckAlthough wartime salvage parties managed to scavenge a large amount of ordnance from the grounded Liberty ship, her hull split in two and sank, taking around 1,400 tonnes of explosives down with her, before the job could be completed. Officials decided to leave the wreck in place.

According to a 1995 survey report [PDF] on the wreck: “The bombs thought to be on board are of two types. The bulk are standard, un-fused TNT bombs. In addition, some 800 fused cluster bombs are believed to remain. These bombs were loaded with TNT. They could be transported fused because the design included a propeller mechanism at the front which only screwed the fuse into position as the bombs fell from an aircraft. All the bombs could therefore be handled – with care – when the accident occurred.”

[…]

The 1995 report noted that TNT “does not react with water and will not explode if it is damp”, before adding that the brass-cased cluster bombs’ lead-based fuses “will combine with brass to produce a highly unstable copper compound which could explode with the slightest disturbance”. Although the compound “if formed, will wash away in a few weeks”, it was not made clear in the report how often the compound forms and creates the dangerous hair-trigger condition. Experts believe that the best way of keeping the wreck safe is not to disturb it, which led to a 500-metre exclusion zone being imposed around it.

I thought the ship’s name sounded familiar … I posted a video about the dangers of this wreck back in 2013. Last month, I posted a video about the Liberty ship program.

January 9, 2018

The ongoing financial catastrophe that is the National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy

Ted Campbell rounds up recent discussions of the Canadian government’s farcical National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS):

There is a somewhat biased but still very useful look at the successes of the National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS) in the Ottawa Citizen by Howie Smith who is the Past President of the Naval Association of Canada. Mr Smith is a retired Canadian naval officer who has provided consultancy services to several firms pursuing opportunities within the projects of the National Shipbuilding Strategy, which is why his article is somewhat biased. Mr Smith is responding to a recent report by Professor Michael Byers of the University of British Columbia, who is also a biased commentator on defence issues, which said that the NSPS “was flawed from the outset” and “According to Byers, the Liberal government should open-up the non-contractually-binding umbrella agreements with Irving and Seaspan, then cancel and restart the Canadian Surface Combatant and the Joint Support Ship procurement programs with fixed-price competitions involving completely ‘off the shelf’ designs.”

It is important, I believe, to understand why Canada needed something like the NSPS in the first place. The notion came in about the middle of the Harper government’s term in office – in around 2010. I think that two problems confronted the government:

- The Canadian shipbuilding industry was, once again, “on the ropes;” Davie, Canada’s largest shipyard was in bankruptcy and the other yards were too reliant on government contracts; and

- Both of the major federal fleets (the Royal Canadian Navy and the Canadian Coast Guard) were approaching “rust out,” again.

The solution to the first problem was to modernize the yards and make them internationally competitive … but that would cost money and private investment money is scarce ~ especially for shipbuilding, plus under the international trade rules to which Canada has agreed direct government subsidies to commercial shipyards are prohibited. The solution to shipyards that are too reliant on government contracts was ~ wait for it ~ another big government contract that would allow them to modernize themselves.

That indirect government subsidy is perfectly legal if the contracts are for navy and coast guard ships because “national security” is a big loophole in international trade law.

Both Professor Byers and Mr Smith have some good points … but neither is 100% correct. The NSPS was and remains a sound idea … the costs, which is the real crux of Professor Byers’ complaint, are not relevant because the defence and coast guard budgets are being (mis)used for industrial development ~ those are not the real costs of warships: they are the real costs of warships PLUS the cost of yard modernization.

The new surface combatant project is, as Mr Smith says, the biggest and costliest peacetime military procurement ever … and the NSPS is working just about a well as any “system” would at bringing it to fruition. At some point in the future a government will have to decide if Canada gets fewer ships than it needs or spends more more money than it wants … or, most likely, both.

That last sentence has always been the most likely outcome: the RCN will get fewer ships than it needs, and those ships will be significantly more expensive per hull than they need to be. The need for modern naval vessels isn’t the top priority … it’s probably not even in the top three priorities as far as the government is concerned (directing money to the “right” recipients, pandering to provincial sensibilities, lots of photo ops, and then maybe the actual needs of the RCN and CCG).

Update: Of course, it’s not like Canada is unique in the problems we have in military procurement … Australia is also struggling in a similar way:

The [Royal Australian] Navy’s program to replace the Collins Class submarines is known as SEA 1000. It involves modification of a French Barracuda Class submarine from nuclear to diesel-electric propulsion, plus other changes specific to Australia.

The 12 new submarines, to be known as Shortfin Barracudas, are intended to begin entering service in the early 2030s with construction extending to 2050. The program is estimated to cost $50 billion and will be the largest and most complex defence acquisition project in Australian history.

[…]

Then there’s the decision to build them in Australia. The Abbott government’s 2016 Defence White Paper only committed to building them in Australia if it could be done without compromising capability, cost or project schedule. That changed because of South Australian politics, and the new submarines could now be more appropriately described as the Xenophon class.

Even if all goes well, the cost of building warships in Australia will be 30 to 40 per cent more than if they were built overseas. However, the plan to build them in Adelaide at the Australian Submarine Corporation, the same group currently building the Air Warfare Destroyer, years late and a billion dollars over budget, adds to a sense of foreboding.

This follows the prize fiasco of the Collins Class submarine project. Their construction by the Australian Submarine Corporation ran years behind schedule, many millions over budget, and finally delivered a platform that the Navy has struggled to even keep operational.

And then there is the question of whether the new submarines will arrive before the Collins Class subs are retired, scheduled for 2026 to 2033. Even if delivery occurs on schedule, the first will not enter service until 2033. At best there will be one new submarine in service and a nine year gap between the retirement of the Collins Class and the introduction into service of the first six of the twelve new submarines.

Given this, the government has apparently committed an additional $15 billion to keep the 30 year old Collins submarines bobbing in the water. It’s like refurbishing a World War 2 German U-Boat for the mid-1990s.

The elements are all there for the submarine replacement program to become the procurement scandal of the century. Our Shortfin Barracudas will probably be the most expensive submarines ever built anywhere in the world.

For a lot less money, we could achieve a far more potent submarine capability. For example, off-the-shelf Japanese Soryu submarines cost only US$540 million. Modified to meet additional Navy requirements, they were quoted as costing A$750 million. If we simply bought twelve of those, the total cost to the taxpayer would be less than A$10 billion.

Equally, the existing nuclear Barracudas only cost $2 billion each, so we could get twelve of those for $24 billion.

For such an important defence capability, the government’s failure to guarantee Australia is protected by submarines is nothing less than gross negligence.

December 28, 2017

How A Cargo Ship Helped Win WW2: The Liberty Ship Story

Mustard

Published on 14 Nov 2017During World War Two, hundreds of cargo ships raced across the Atlantic in an effort to keep Britain supplied. But these ships were being sunk by German U-boats, warships and aircraft. In 1940 alone, over a thousand allied ships were lost on their way to Britain.

The United States, while not yet at war, was playing a vital role in supplying Britain. But with ships being sunk daily, Britain and America desperately needed a way to keep all that material moving across the Atlantic. In response, 18 shipyards across the coastal United States mobilized to build thousands of large cargo ships known as Liberty Ships. They would be built even faster than the enemy could sink them. At one point the shipyards were building one large Liberty Ship every eight hours.

Two revolutionary changes in shipbuilding will make this enormous feat possible. The first is welding and the second is the use of a modular assembly process. By mid 1941, the sheer number Liberties out at sea, along with increasing armed escorts overwhelmed German forces. Advances in anti-submarine technologies also started stamping out the U-boat threat.

Today, there are only three Liberty Ships remaining of the 2,710 built that remind us of their enormous contribution to winning World War Two.

December 6, 2017

The RCN doesn’t need a second supply ship, says Transport Minister Garneau

David Pugliese on the latest military inanity from the federal government:

Politicians and unions in Quebec are turning up the heat on the Liberal government, questioning why Davie shipyards in the province isn’t getting any more work from the federal government. Davie converted a commercial container ship into a supply vessel for the Royal Canadian Navy. It was on time and on budget. The ship, the Asterix, goes into service early next year and under the agreement will be leased to the RCN.

Davie is ready to quickly convert another vessel into a supply ship.

But Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government has said thanks but no thanks.

Transport Minister, and former navy officer, Marc Garneau said the federal government doesn’t need another supply ship. ” We cannot artificially create a need for something that doesn’t exist,” he told reporters on the weekend.

An artificial need?

Seaspan shipyards in Vancouver and the Department of National Defence don’t project the first Joint Support Ship (being built by Seaspan) arriving until early 2021. But that ship would still have to undergo testing, etc. So, let’s say that the first JSS is ready for operations by the end of 2021.

That means that the RCN will have one supply ship to support its fleets operating on two coasts. How is that going to work?