Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 12 Nov 2024Casserole made from sliced potatoes, fennel, and caraway served with pickled beets

City/Region: Germany

Time Period: 1941How well people ate in Germany during WWII really depended on who they were, where they were, and how long the war had been going on. This recipe, from 1941, assumes that people will still have access to ingredients like milk and eggs, which would become extremely scarce for most people in later years.

If you like the anise-like flavors of fennel and caraway, this dish is for you. The flavors are very prominent and really take over the whole casserole. If you’re not too concerned about historical accuracy with this one, I think some more milk or the addition of some cream or cheese would be delicious and add some moisture.

Fennel and Potato Casserole

1 kg fennel, 1 kg potatoes, 1/3 L milch, 1 egg, 30 g flour, 2 spoons nutritional yeast, caraway, salt

If necessary, remove the outer leaves from the fennel bulbs and cut off the green ones. Then cut them and the raw peeled potatoes into slices. Layer them in a greased baking dish, alternating with salt and caraway and the finely chopped fennel greens. The top layer is potatoes. Pour the milk whisked with an egg and a tablespoon of yeast flakes over it. Sprinkle with caraway and yeast flakes and bake the casserole for about 1 hour. — Serve with pickled beets or green salad.

— Frauen-Warte, 1941.

March 26, 2025

Cooking on the German Home Front During World War 2

February 18, 2025

World War 2 rations on the British Home Front

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 8 Oct 2024Mock banana cream on whole grain National Loaf

City/Region: United Kingdom

Time Period: 1944British rationing lasted from 1940 all the way to 1954, and they had to completely do without foods like bananas for years. The National Loaf began to be distributed in 1941. Made of 85% wholemeal flour enriched with vitamins B and C, it was nutritious, but dense, gummy, and went stale very quickly.

My National Loaf, based on the Imperial War Museum’s version, is dense, but I like the complex flavors from the whole grains. The mock banana cream has a texture that’s really close to mashed bananas, though the taste is an interesting mixture of parsnip and banana. Not bad, but not quite banana.

Mock Banana Cream

Here is a more economical banana cream recipe. Prepare and boil 1lb. parsnips until soft. Add 2 ozs margarine, 1 level tablespoonful sugar, 2 teaspoonfuls banana flavouring and beat until creamy. This must be used quickly, but half the quantity can be made if desired.

— Daily Record, Glasgow, May 27, 1944

January 21, 2025

January 17, 2025

QotD: Foraging for supplies in pre-modern armies

We should start with the sort of supplies our army is going to need. The Romans neatly divided these into four categories: food, fodder, firewood and water each with its own gathering activities (called by the Romans frumentatio, pabulatio, lignatio and aquatio respectively; on this note Roth op. cit. 118-140), though gathering food and fodder would be combined whenever possible. That’s a handy division and also a good reflection of the supply needs of armies well into the gunpowder era. We can start with the three relatively more simple supplies, all of which were daily concerns but also tended to be generally abundant in areas that armies were.

For most armies in most conditions, water was available in sufficient quantities along the direction of march via naturally occurring bodies of water (springs, rivers, creeks, etc.). Water could still be an important consideration even where there was enough to march through, particularly in determining the best spot for a camp or in denying an enemy access to local water supplies (such as, famously at the Battle of Hattin (1187)). And detailing parties of soldiers to replenish water supplies was a standard background activity of warfare; the Romans called this process aquatio and soldiers so detailed were aquatores (not a permanent job, to be clear, just regular soldiers for the moment sent to get water), though generally an army could simply refill its canteens as it passed naturally occurring watercourses. Well organized armies could also dig wells or use cisterns to pre-position water supplies, but this was rarely done because it was tremendously labor intensive; an army demanded so much water that many wells would be necessary to allow the army to water itself rapidly enough (the issue is throughput, not well capacity – you can only lift so many buckets of so much water in an hour in a single well). For the most part armies confined their movements to areas where water was naturally available, managing, at most, short hops through areas where it was scarce. If there was no readily available water in an area, agrarian armies simply couldn’t go there most of the time.

Like water, firewood was typically a daily concern. In the Roman army this meant parties of firewood forages (lignatores) were sent out regularly to whatever local timber was available. Fortunately, local firewood tended to be available in most areas because of the way the agrarian economy shaped the countryside, with stretches of forest separating settlements or tended trees for firewood near towns. Since an army isn’t trying to engage in sustainable arboriculture, it doesn’t usually need to worry about depleting local wood stocks. Moreover, for our pre-industrial army, they needn’t be picky about the timber for firewood (as opposed to timber for construction). Like water gathering, collecting firewood tends to crop up in our sources when conditions make it unusually difficult – such as if an army is forced to remain in one place (often for a siege) and consequently depletes the local supply (e.g. Liv. 36.22.10) or when the presence of enemies made getting firewood difficult without using escorts or larger parties (e.g. Ps.-Caes. BAfr. 10). Sieges could be especially tricky in this regard because they add a lot of additional timber demand for building siege engines and works; smart defenders might intentionally try to remove local timber or wood structures to deny an approaching army as part of a scorched earth strategy (e.g. Antioch in 1097). That said apart from sieges firewood availability, like water availability is mostly a question of where an army can go; generals simply long stay in areas where gathering firewood would be impossible.

Then comes fodder for the animals. An army’s animals needed a mix of both green fodder (grass, hay) and dry fodder (barley, oats). Animals could meet their green fodder requirements by grazing at the cost of losing marching time, or the army could collect green fodder as it foraged for food and dry fodder. As you may recall, cut grain stalks can be used as green fodder and so even an army that cannot process grains in the fields can still quite easily use them to feed the animals, alongside barley and oats pillaged from farm storehouses. The Romans seem to have preferred gathering their fodder from the fields rather than requisitioning it from farmers directly (Caes. BG 7.14.4) but would do either in a pinch. What is clear is that much like gathering water or firewood this was a regular task a commander had to allot and also that it often had to be done under guard to secure against attacks from enemies (thus you need one group of soldiers foraging and another group in fighting trim ready to drive off an attack). Fodder could also be stockpiled when needed, which was normally for siege operations where an army’s vast stock of animals might deplete local grass stocks while the army remained encamped there. Crucially, unlike water and firewood, both forms of fodder were seasonal: green fodder came in with the grasses in early spring and dry fodder consists of agricultural products typically harvested in mid-summer (barley) or late spring (oats).

All of which at last brings us to the food, by which we mostly mean grains. Sources discussing army foraging tend to be heavily focused on food and we’ll quickly see why: it was the most difficult and complex part of foraging operations in most of the conditions an agrarian army would operate. The first factor that is going to shape foraging operations is grain processing. [S]taple grains (especially wheat, barley and later rye) make up the vast bulk of the calories an army (and it attendant non-combatants) are eating on the march. But, as we’ve discussed in more detail already, grains don’t grow “ready to eat” and require various stages of processing to render them edible. An army’s foraging strategy is going to be heavily impacted by just how much of that processing they are prepared to do internally.

This is one area where the Roman army does appear to have been quite unusual: Roman armies could and regularly did conduct the entire grain processing chain internally. This was relatively rare and required both a lot of coordination and a lot of materiel in the form of tools for each stage of processing. As a brief refresher, grains once ripe first have to be reaped (cut down from the stalks), then threshed (the stalks are beaten to shake out the seeds) and winnowed (the removal of non-edible portions), then potentially hulled (removing the inedible hull of the seed), then milled (ground into a powder, called flour, usually by the grinding actions of large stones), then at last baked into bread or a biscuit or what have you.

It is possible to roast unmilled grain seeds or to boil either those seeds or flour in water to make porridge in order to make them edible, but turning grain into bread (or biscuits or crackers) has significant nutritional advantages (it breaks down some of the plant compounds that human stomachs struggle to digest) and also renders the food a lot tastier, which is good for morale. Consequently, while armies will roast grains or just make lots of porridge in extremis, they want to be securing a consistent supply of bread. The result is that ideally an army wants to be foraging for grain products at a stage where it can manage most or all of the remaining steps to turn those grains into food, ideally into bread.

As mentioned, the Romans could manage the entire processing chain themselves. Roman soldiers had sickles (falces) as part of their standard equipment (Liv. 42.64.2; Josephus BJ 3.95) and so could be deployed directly into the fields (Caes. BG 4.32; Liv. 31.2.8, 34.26.8) to reap the grain themselves. It would then be transported into the fortified camp the Romans built every time the army stopped for the night and threshed by Roman soldiers in the safety of the camp (App. Mac. 27; Liv. 42.64.2) with tools that, again, were a standard part of Roman equipment. Roman soldiers were then issued threshed grains as part of their rations, which they milled themselves (or made into a porridge called puls) using “handmills”. These were not small devices, but roughly 27kg (59.5lbs) hand-turned mills (Marcus Junkelmann reconstructed them quite ably); we generally assume that they were probably carried on the mules on the march, one for each contubernium (tent-group of 6-8; cf. Plut. Ant. 45.4). Getting soldiers to do their own milling was a feat of discipline – this is tough work to do by hand and milling a daily ration would take one of the soldiers of the group around two hours. Roman soldiers then baked their bread either in their own campfires (Hdn 4.7.4-6; Dio Cass. 62.5.5) though generals also sometimes prepared food supplies in advance of operations via what seem to be central bakeries. This level of centralization was part and parcel of the unusual sophistication of Roman logistics; it enabled a greater degree of flexibility for Roman armies.

Greek hoplite armies do not seem generally to have been able to reap, thresh or mill grain on the march (on this see J.W. Lee, op. cit.; there’s also a fantastic chapter on the organization of Greek military food supply by Matthew Sears forthcoming in a Brill Companion volume one of these years – don’t worry, when it appears, you will know!). Xenophon’s Ten Thousand are thus frequently forced to resort to making porridge or roast grains when they cannot forage supplies of already-milled-flour; they try hard to negotiate for markets on their route of march so they can just buy food. Famously the Spartan army, despoiling ripe Athenian fields runs out of supplies (Thuc. 2.23); it’s not clear what sort of supplies were lacking but food and fodder seems the obvious choice, suggesting that the Spartans could at best only incompletely utilize the Athenian grain. All of which contributed to the limited operational endurance of hoplite armies in the absence of friendly communities providing supplies.

Macedonian armies were in rather better shape. Alexander’s soldiers seem to have had handmills (note on this Engels, op. cit.) which already provides a huge advantage over earlier Greek armies. Grain is generally (as noted in our series on it) stored and transported after threshing and winnowing but before milling because this is the form in which has the best balance of longevity and compactness. That means that granaries and storehouses are mostly going to contain threshed and winnowed grains, not flour (nor freshly reaped stalks). An army which can mill can thus plunder central points of food storage and then transport all of that food as grain which is more portable and keeps better than flour or bread.

Early modern armies varied quite a lot in their logistical capabilities. There is a fair bit of evidence for cooking in the camp being done by the women of the campaign community in some armies, but also centralized kitchen messes for each company (Lynn op. cit. 124-126); the role of camp women in food production declines as a product of time but there is also evidence for soldiers being assigned to cooking duties in the 1600s. On the other hand, in the Army of Flanders seems to have relied primarily on external merchants (so sutlers, but also larger scale contractors) to supply the pan de munición ration-bread that the army needed, essentially contracting out the core of the food system. Parker (op. cit. 137) notes the Army of Flanders receiving some 39,000 loaves of bread per day from its contractors on average between April 1678 and February of 1679.

That created all sorts of problems. For one, the quality of the pan de munición was highly variable. Unlike soldiers cooking for themselves or their mess-mates, contractors had every incentive to cut corners and did so. Moreover, much of this contracting was done on credit and when Spanish royal credit failed (as it did in 1557, 1560, 1575, 1596, 1607, 1627, 1647 and 1653, Parker op. cit. 125-7) that could disrupt the entire supply system as contractors suddenly found the debts the crown had run up with them “restructured” (via a “Decree of Bankruptcy”) to the benefit of Spain. And of course that might well lead to thousands of angry, hungry, unpaid men with weapons and military training which in turn led to disasters like the Sack of Antwerp (1576), because without those contractors the army could not handle its logistical needs on its own. It’s also hard not to conclude that this structure increased the overall cost of the Army of Flanders (which was astronomical) because it could never “make the war feed itself” in the words of Cato the Elder (Liv 34.9.12; note that it was rare even for the Romans for a war to “feed itself” entirely through forage, but one could at least defray some costs to the enemy during offensive operations). That said this contractor supplied bread also did not free the Army of Flanders from the need to forage (or even pillage) because – as noted last time – their rations were quite low, leading soldiers to “offset” their low rations with purchase (often using money gained through pillage) or foraging.

Of course added to this are all sorts of food-stuffs that aren’t grain: meat, fruits, vegetables, cheeses, etc. Fortunately an army needs a lot less of these because grains make up the bulk of the calories eaten and even more fortunately these require less processing to be edible. But we should still note their importance because even an army with a secure stockpile of grain may want to forage the surrounding area to get supplies of more perishable foodstuffs to increase food variety and fill in the nutritional gaps of a pure-grain diet. The good news for our army is that the places they are likely to find food (small towns and rural villages) are also likely to be sources of these supplementary foods. By and large that is going to mean that armies on the march measure their supplies and their foraging in grain and then supplement that grain with whatever else they happen to have obtained in the process of getting that grain. Armies in peacetime or permanent bases may have a standard diet, but a wartime army on the march must make do with whatever is available locally.

So that’s what we need: water, fodder, firewood and food; the latter mostly grains with some supplements, but the grain itself probably needs to be in at least a partially processed form (threshed and sometimes also milled), in order to be useful to our army. And we need a lot of all of these things: tons daily. But – and this is important – notice how all of the goods we need (water, firewood, fodder, food) are things that agrarian small farmers also need. This is the crucial advantage of pre-industrial logistics; unlike a modern army which needs lots of things not normally produced or stockpiled by a civilian economy in quantity (artillery shells, high explosives, aviation fuel, etc.), everything our army needs is a staple product or resource of the agricultural economy.

Finally we need to note in addition to this that while we generally speak of “forage” for supplies and “pillage” or “plunder” for armies making off with other valuables, these were almost always connected activities. Soldiers that were foraging would also look for valuables to pillage: someone stealing the bread a family needs to live is not going to think twice about also nicking their dinnerware. Sadly we must also note that very frequently the valuables that soldiers looted were people, either to be sold into slavery, held for ransom, pressed into work for the army, or – and as I said we’re going to be frank about this – abducted for the purpose of sexual assault (or some combination of the above).

And so a rural countryside, populated by farms and farmers is in essence a vast field of resources for an army. How they get them is going to depend on both the army’s organization and capabilities and the status of the local communities.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Logistics, How Did They Do It, Part II: Foraging”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-07-29.

December 15, 2024

Cooking on the American Homefront During WWII

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Aug 6, 2024T-bone shaped seasoned ground beef with Wheaties

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1943Rationing didn’t begin in the United States until May 1942, and in order to buy certain foods, you used a combination of stamps and money. Better cuts of meat required more stamps, so there came a slew of recipes that either replaced meat, or made lesser cuts seem like better ones, like this recipe.

This “emergency steak” is actually very nice. It’s essentially a kind of meatloaf, and is surprisingly flavorful given the scant ingredient list. Is it like a T-bone steak? No. Is it tasty? Yes.

Emergency Steak

(1 lb.—serves 6)

Mix …

1 lb. ground beef or hamburger

1/2 cup milk

1 cup WHEATIES

1 tsp. salt

1/4 tsp. pepper

1 tbsp. chopped onion

Place on pan, pat into T-bone steak shape, 1 in. thick. Broil 8 to 15 min. at 500° (very hot). Turn once.

Meats … 7

— Your Share by Betty Crocker (General Mills), 1943

November 1, 2024

“[H]er plan will mean the obliteration of your savings, the end of banks and even the destruction of ‘money as we know it'”

It’s astonishing how many highly placed bureaucrats, NGO functionaries, and the very, very wealthy are super gung-ho for reducing the rest of us to the status (and living conditions) of medieval serfs:

This week, VW announced plans to cut tens of thousands of jobs and to close three factories. That is a very big deal, because they have never closed a single German factory before. I try to avoid economic topics, but this story is so much bigger than economics. As Daniel Gräber wrote in Cicero last month, “the VW crisis has become a symbol for the decline of our entire country“.

The Green leftoid establishment are eagerly blaming management for these failures, which is on the one hand not entirely wrong, but on the other hand not nearly an absolution. The German state of Lower Saxony holds a 20% stake in Volkswagen, and so they also manage the company. Recently, in a fit of virtue, they placed a Green politician – Julia Willie Hamburg – on its supervisory board. Hamburg does not even own a car and has used her position to argue that Volkswagen should regard itself not as an automobile manufacturer but as a “mobility services provider” and shift its focus away from “individual transport”.

The absurdly named Julia Willie Hamburg is merely symptomatic of a broader phenomenon. Germany has succumbed to political forces that have nothing but indifference and disdain for the industries that have made us prosperous. Our sitting Economics Minister, Robert Habeck, gave an interview to taz in 2011 in which he said that “fewer cars will not lead to less economic growth, but to new industries”, and attacked “the old growth theory, based on gross domestic product“. And behind Green politicians like Habeck are even more radical forces, like Ulrike Herrmann, the editor of taz, for many years a member of the Green Party and also an open advocate of wide-scale deindustrialisation. Because I am going to quote Herrmann saying some very crazy things, you need to know that she is in no way a fringe figure. She appears regularly on all the respectable evening talkshows and every politically informed person in the Federal Republic knows who she is.

Herrmann has outlined her political views in various books like The End of Capitalism: Why Growth and Climate Protection Are Not Compatible – and How We Will Live in the Future. From these monographs, we learn that Herrmann sees climatism as a means of imposing a centrally planned economy in which we will own nothing and be happy. Happily, Herrmann also talks a lot, and in her various speeches and interviews she states her vision for decarbonising Germany in very radical terms. I am grateful to this twitter user for highlighting typical remarks that Herrmann delivered in April of this year before a sympathetic audience of climate lunatics.

There, Herrmann elaborated on her vision for a future economy in which all major goods would have to be rationed:

Talking about rationing: It’s clear that if we shrink economically, we won’t have to be as poor as the British were in 1939; rather, we’d have to be as rich as the West Germans were in 1978. That is a huge difference, because we can take advantage of all the growth of the post-war period and the entire economic miracle.

The central elements of the economy would have to be rationed. First of all, living space, because cement emits endless amounts of CO2. Actually, new construction would have to be banned outright and living space rationed to 50 square metres per capita. That should actually be enough for everyone. Then meat would have to be rationed, because meat production emits enormous amounts of CO2. You don’t have to become a vegetarian, but you’ll have to eat a lot less meat.

Then train travel has to be rationed. So this idea, which many people also have – “so okay then I don’t have a car but then I always travel on the Intercity Express trains” – that won’t work either, because of course air resistance increases with speed. Yes, it’s all totally insane. Trains won’t be allowed to travel faster than 100 kilometres per hour, but you can still travel around locally quite a lot. This is all in my book, okay? But I didn’t expand on it there because I didn’t want to scare all the readers.

At this point Herrmann begins to cackle manically, ecstatic at the thought that millions of Germans will be stuck riding rationed kilometres on slow local public transit.

August 27, 2024

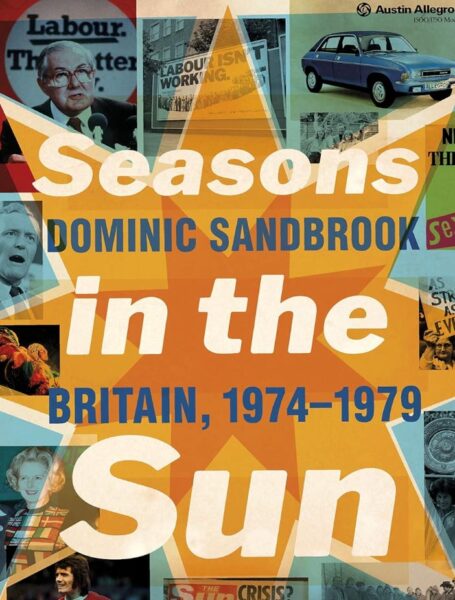

Was 1974 the worst year in British politics or just the worst year so far?

I wasn’t in the UK in 1974 (although I did spend a couple of dystopian weeks there in January 1979), so I don’t know from personal experience just how bad things were, but as Ed West considers Dominic Sandbrook’s very informative social history Seasons in the Sun, he certainly helps make a strong case for it:

One of my favourite moments from reading Fever Pitch as a teenager was the passage where Nick Hornby and a friend bunk off school to watch Arsenal play West Ham, a game which was being held on a weekday afternoon because there wasn’t enough electricity for the floodlights. Britain was enduring a three-day week due to the energy crisis, and assuming the ground would be empty, Hornby is stunned to find it packed with 60,000 people, all skiving off work, and he recalls his hypocritical juvenile disgust at the idleness of the British public.

The scene encapsulates the comic crapness of that period, one that many of us have enjoyed laughing at with the recent Rest is History series on 1974. I began reading Sandbrook’s book Seasons in the Sun afterwards, from where the material for the series was drawn; the early chapters comprise a highly entertaining account of what he described on the podcast as “the worst year in British politics”. Reassuring, perhaps, for those of us inclined towards pessimism, although to paraphrase Homer Simpson, perhaps it was only the worst year so far.

Nineteen-seventy-four saw two elections, the first of which ended in a hung parliament, with Labour as the largest party, and the second with Harold Wilson winning with a majority of 3. These were fought between parties led by exhausted leaders who had run out of ideas, with a third, the Liberals headed by Jeremy Thorpe, soon to be notorious as a dog killer. Britain had declined from the richest country on the continent to one of the poorest in western Europe, and its economy seemed to be falling apart.

During his troubled four years in office Edward Heath had called a state of emergency several times, culminating in ration cards for petrol and power restrictions. In 1973 Heath had “told his Chancellor, Anthony Barber, to go for broke”, Sandbrook writes: “It was one of the greatest economic gambles in modern history: while credit soared and the money supply boomed, Heath hoped to keep inflation down through an elaborate system of wage and price controls”. By October that year, “his hopes were unravelling at terrifying speed”.

The “Barber boom” led to “house prices surging by 25 per cent in just six months, the cost of imports rocketing and Britain’s trade balance plunging deep into the red”. Yet just a week after Heath had published details of his “Stage Three” incomes policy, “the Arab oil exporters in the OPEC cartel announced a stunning 70 per cent increase in the posted price of oil, punishing the West for its support for Israel. It was a devastating blow to the world economy, but nowhere was its impact greater than in Britain.”

The stock market lost a quarter of its value in just a month, while by January 1974 share prices had fallen by almost half in under two years. Just before Christmas, the government cut spending by 4 per cent, and Labour’s Shadow Chancellor, Denis Healey, “warned his colleagues that Britain stood on the brink of an ‘economic holocaust'”. Nine out of ten people told a Harris poll that “things are going very badly for Britain” and nearly as many foresaw no improvement in the coming year. They turned out to be correct.

Amid trouble with the National Union of Mineworkers, in November 1973 “Heath announced his fifth state of emergency in barely four years. Floodlighting and electric advertising were banned; behind the scenes, the government began printing petrol ration cards. As the railwaymen voted to join the miners in pursuit of higher pay, it seemed that Britain was sliding into darkness. Offices were ordered to turn down their thermostats, while the BBC and ITV were banned from broadcasting after 10.30 at night. On New Year’s Day, with fuel supplies running dangerously low, the entire nation went on a three-day working week.” Happy days.

August 24, 2024

Eating on a German U-Boat in WW1

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published May 7, 2024Sauerkraut soup served with German black bread, or schwarzbrot

City/Region: Germany

Time Period: 1915The food aboard a German U-boat could get really monotonous, especially after the first ten days or so, when all of the best and freshest ingredients would have gone bad. This simple soup uses ingredients that would have been available on board, and comes from a German cookbook from WWI. There are actually several variations of this soup in the cookbook, the only difference being swapping out the sauerkraut for other ingredients like pickles, cabbage, or beets.

You need to like sauerkraut in order to enjoy this soup, as there isn’t anything else going on to contribute other flavors. I highly recommend eating it with some schwarzbrot, or black bread. It balances the sourness of the soup and the two go together very nicely.

Sauerkrautsuppe

The fat and flour are whisked and the water is slowly added. When the soup has simmered, the sauerkraut is added. Salt and vinegar are added to the soup and seasoned.

— Kriegskochbuch, 1915.

June 29, 2024

Oh no! The filthy proles are getting too many calories! Let’s re-impose rationing!

Tim Worstall suggests that the regular “viewing with alarm” thumbsuckers about purchased meals having “too many calories” are actually an indication of a strong desire by the great and the good to stick their regulatory noses into the lives of ordinary people:

“Indian take away in Farrer Park” by Kai Hendry is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

This headline is, of course, wrong.

Some takeaway meals contain more calories than daily limit, UK study finds

There is no daily limit. We do not have laws stating how much food we are allowed to eat. Of course, there are those who want there to be such laws but there aren’t, as yet. What there is is a series of recommendations about the limits we should impose upon ourselves:

Some takeaway meals contain more calories in one sitting than someone is advised to consume in an entire day, a study of British eating habits has revealed.

That’s better.

Cafes, fast-food outlets, restaurants, bakeries, pubs and supermarkets are fuelling the UK’s obesity crisis because so many meals they sell contain dangerously large numbers of calories, it found.

That’s not better. Because a plate of food containing a lot of calories is not a danger. Eating many of them might be but that the average household can get a gutbuster for some trivial portion of household earnings is a glory of modern civilisation, the very proof we require that we’re all as rich as Croesus.

And this is actually true too. That we are gloriously rich and it’s our food supply that proves this. As Brad Delong likes to point out back 200 years (yes, about right, 1820s is as it was really changing but 300 years would be better) it took a full day’s work to be able to gain 2,000 calories a day for a day labourer. There are 800 million out there still living at that standard of living. We can buy 2,000 calories — if we go boring stodge — for 30 minutes work now.

By history and by certain geographies we are foully rich these days. Which is the complaint of the wowsers of course. They’re a revival of the puritans and their sumptuary laws. How dare it be true that people fill their bellies with food they actually like?

Six out of 10 takeaway meals contain more than the 600-calorie maximum that the government recommends people should stick to for lunch and dinner in order to not gain weight, according to the research, which was carried out by the social innovation agency Nesta.

One in three contain at least 1,200 calories – double the recommended limit.

And? So, folk can buy lots of food for not much money. This is the very thing that makes having a civilisation possible — cheap food. My wife and I do indeed partake of an Indian occasionally — and find the takeout portions rather large. So, we have one amount for lunch or dinner and we’ve a refrigerator in which to keep the excess for a supper or snack another day. This is not beyond the wit of man to organise.

We don’t order in food very often, but when we do we usually manage to get both dinner on the night and lunch on the morrow from a typical order. If the nosey parkers have their way, they’d limit what we were allowed to buy — for our own good, of course — so we’d almost certainly still pay the same amount for less food. Such a deal!

June 10, 2024

QotD: The British sweet tooth

It will be seen that British cookery displays more variety and more originality than foreign visitors are usually ready to allow, and that the average restaurant or hotel, whether cheap or expensive is not a trustworthy guide to the diet of the great mass of the people. Every style of cookery has its peculiar faults, and the two great shortcomings of British cookery are a failure to treat vegetables with due seriousness, and an excessive use of sugar. At normal times the average consumption of sugar per head is very much higher than in most countries, and all British children and a large proportion of adults are over-much given to eating sweets between meals. It is, of course, true that sweet dishes and confectionery – cakes, puddings, jams, biscuits and sweet sauces – are the especial glory of British cookery but the national addiction to sugar has not done the British palate any good. Too often it leads people to concentrate their main attention on subsidiary foods and to tolerate bad and unimaginative cookery in the main dishes. Part of the trouble is that alcohol, even beer, is fantastically expensive and has therefore come to be looked on as a luxury to be drunk in moments of relaxation, not as an integral part of the meal. The majority of people drink sweetened teas with at least two of their daily meals, and it is therefore only natural that they should want the food itself to taste excessively sweet. The innumerable bottled sauces and pickles which are on sale in Britain are also enemies of good cookery. There is reason to think, however, that the standard of British cookery – that is, cookery inside the home – has gone up during the war years, owing to the drastic rationing of tea, sugar, meats and fats. The average housewife has been compelled to be more economical then she used to be, to pay more attention to the seasoning of soups and stews, and to treat vegetables as a serious foodstuff and less a neglected sideline.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

June 6, 2024

QotD: Herbert Hoover as Woodrow Wilson’s “Food Dictator”

In 1917, America enters World War I. Hoover […] returns to the US a war hero. The New York Times proclaims Hoover’s CRB work “the greatest American achievement of the last two years”. There is talk that he should run for President. Instead, he goes to Washington and tells President Woodrow Wilson he is at his service.

Wilson is working on the greatest mobilization in American history. He realizes one of the US’ most important roles will be breadbasket for the Allied Powers, and names Hoover “food commissioner”, in charge of ensuring that there is enough food to support the troops, the home front, and the other Allies. His powers are absurdly vast – he can do anything at all related to the nation’s food supply, from fixing prices to confiscating shipments from telling families what to eat. The press affectionately dubs him “Food Dictator” (I assume today they would use “Food Czar”, but this is 1917 and it is Too Soon).

Hoover displays the same manic energy he showed in Belgium. His public relations blitz telling families to save food is so successful that the word “Hooverize” enters the language, meaning to ration or consume efficiently. But it turns out none of this is necessary. Hoover improves food production and distribution efficiency so much that no rationing is needed, America has lots of food to export to Europe, and his rationing agency makes an eight-digit profit selling all the extra food it has.

By 1918, Europe is in ruins. The warring powers have declared an Armistice, but their people are starving, and winter is coming on fast. Also, Herbert Hoover has so much food that he has to swim through amber waves of grain to get to work every morning. Mountains of uneaten pork bellies are starting to blot out the sky. Maybe one of these problems can solve the other? President Wilson dispatches Hoover to Europe as “special representative for relief and economic rehabilitation”. Hoover rises to the challenge:

Hoover accepted the assignment with the usual claim that he had no interest in the job, simultaneously seeking for himself the broadest possible mandate and absolute control. The broad mandate, he said, was essential, because he could not hope to deliver food without refurnishing Europe’s broken finance, trade, communications, and transportation systems …

Hoover had a hundred ships filled with food bound for neutral and newly liberated parts of the Continent before the peace conferences were even underway. He formalized his power in January 1919 by drafting for Wilson a post facto executive order authorizing the creation of the American Relief Administration (ARA), with Hoover as its executive director, authorized to feed Europe by practically any means he deemed necessary. He addressed the order to himself and passed it to the president for his signature …

The actual delivery of relief was ingeniously improvised. Only Hoover, with his keen grasp of the mechanics of civilization, could have made the logistics of rehabilitating a war-ravaged continent look easy. He arranged to extend the tours of thousands of US Army officers already on the scene and deployed them as ARA agents in 32 different countries. Finding Europe’s telegraph and telephone services a shambles, he used US Navy vessels and Army Signal Corps employees to devise the best-functioning and most secure wireless system on the continent. Needing transportation, Hoover took charge of ports and canals and rebuilt railroads in Central and Eastern Europe. The ARA was for a time the only agency that could reliably arrange shipping between nations …

The New York Times said it was only apparent in retrospect how much power Hoover wielded during the peace talks. “He has been the nearest approach Europe has had to a dictator since Napoleon.”

Once again, Hoover faces not only the inherent challenge of feeding millions, but opposition from the national governments he is trying to serve. Britain and France plan to let Germany starve, hoping this will decrease its bargaining power at Versailles. They ban Hoover from transporting any food to the defeated Central Powers. Hoover, “in a series of transactions so byzantine it was impossible for outsiders to see exactly what he was up to”, causes some kind of absurd logistics chain that results in 42% of the food getting to Germany in untraceable ways.

He is less able to stop the European powers’ controlled implosion at Versailles. He believes 100% in Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a fair peace treaty with no reparations for Germany and a League Of Nations powerful enough to prevent any future wars. But Wilson and Hoover famously fail. Hoover predicts a second World War in five years (later he lowers his estimate to “thirty days”), but takes comfort in what he has been able to accomplish thus far.

He returns to the US as some sort of super-double-war-hero. He is credited with saving tens of millions of lives, keeping Europe from fraying apart, and preventing the spread of Communism. He is not just a saint but a magician, accomplishing feats of logistics that everyone believed impossible. John Maynard Keynes:

Never was a nobler work of disinterested goodwill carried through with more tenacy and sincerity and skill, and with less thanks either asked or given. The ungrateful Governments of Europe owe much more to the statesmanship and insight of Mr. Hoover and his band of American workers than they have yet appreciated or will ever acknowledge. It was their efforts … often acting in the teeth of European obstruction, which not only saved an immense amount of human suffering, but averted a widespread breakdown of the European system.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

June 5, 2024

What Troops Ate On D-Day – World War 2 Meals & Rations

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published May 21, 2024D-Day Scrambled Eggs and Bacon served with toast and D-Day Lemonade

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1944The food in the final days leading up to D-Day was a definite improvement over the sad, dry sandwiches some soldiers had been getting. All-you-can-eat meals of steak, pork chops, sides, lemon meringue pie, ice cream, and even popcorn and candy during movie screenings kept the sequestered troops well fed. The last meal served before the landing was breakfast in the very early hours of the morning, said by many to be scrambled eggs and bacon.

This meal was made in the south of England, but the bacon was from the U.S., so American-style bacon is best here. The eggs don’t taste bad, but the texture is not like fresh scrambled eggs at all (more like tofu). The bacon is real, though, and that really saves the dish. Powdered eggs can be found online and at camping stores.

No. 749. Scrambled Eggs

Water, cold … 2 1/2 quarts (2 1/2 No. 56 dippers)

Eggs, powdered … 1 1/2 pounds (1/2 3-pound can)

Salt … To taste

Pepper … To taste

Lard or bacon fat … 1 pound (1/2 No. 56 dipper)Sift eggs. Pour 1/3 of the water into a utensil suitable for mixing eggs. Add powdered eggs. Stir vigorously with whip or slit spoon until mixture is absolutely smooth. Tip utensil while stirring.

Add salt, pepper, and remaining water slowly to eggs, stirring until eggs are completely dissolved.

Melt fat in baking pan. Pour liquid eggs into hot fat.

Stir as eggs begin to thicken. Continue stirring slowly until eggs are cooked slightly less than desired for serving.

Take eggs from fire while soft, as they will continue to thicken after being removed from heat.No. 750. Diced Ham (or Bacon) and Scrambled Eggs

Add 3 pounds of ham or bacon to basic recipe for scrambled eggs; omit lard. Fry ham or bacon until crisp and brown.

Pour egg solution over meat and fat. Stir and cook as in basic recipe. Additional fat may be needed if ham is used.

— TM 10-412 US Army Technical Manual. Army Recipes by the U.S. War Department, 1946

April 7, 2024

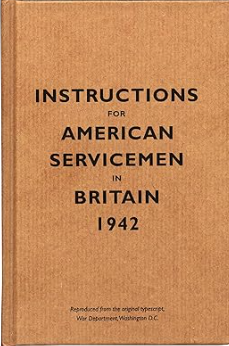

Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain (1942)

Henry Getley on the US War Department publication Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain produced for incoming GIs on arrival in Britain from early in 1942:

[W]ith their troops pouring into this country from 1942 onwards to prepare for D-Day, officials at the US War Department did their best to make the culture clash as trouble-free as possible. One of their main efforts was issuing GIs with a seven-page foolscap leaflet called Instructions for American Servicemen in Britain.

It’s available in reprint as a booklet and makes fascinating reading, not least for its straightforward, jargon-free writing style and its overriding message – telling the Yanks to use “plain common horse sense” in their dealings with the British.

In parts, it now seems clumsy and condescending. But its purpose was praiseworthy – to try to get American troops to damp down the impression that they were overpaid, oversexed and over here. Many GIs qualified in all three aspects, of course, but you couldn’t blame the top brass for trying.

The leaflet paints a sympathetic (some would say patronising) picture for the incoming Americans of a Britain – “a small crowded island of forty-five million people” – that had been at war for three years, having initially stood alone against Hitler and braved the Blitz. Hence this “cradle of democracy” was now a “shop-worn and grimy” land of rationing, the blackout, shortages and austerity. But beneath the shabbiness, there was steel.

The British are tough. Don’t be misled by the British tendency to be soft-spoken and polite. If need be, they can be plenty tough. The English language didn’t spread across the oceans and over the mountains and jungles and swamps of the world because these people were panty-waists.

There were helpful hints about cricket, football, darts, pounds, shillings and pence, warm beer and badly-made coffee. And because we are two nations divided by a common language, the Yanks were urged to listen to the BBC.

In England the “upper crust” speak pretty much alike. You will hear the newscaster for the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). He is a good example, because he has been trained to talk with the “cultured” accent. He will drop the letter “r” (as people do in some sections of our own country) and will say “hyah” instead of “here”. He will use the broad “a”, pronouncing all the a’s in “banana” like the “a” in father.

However funny you may think this is, you will be able to understand people who talk this way and they will be able to understand you. And you will soon get over thinking it’s funny. You will have more difficulty with some of the local accents. It may comfort you to know that a farmer or villager from Cornwall very often can’t understand a farmer or villager in Yorkshire or Lancashire.

The GIs were warned against bravado and bragging, being told that the British were reserved but not unfriendly. “They will welcome you as friends and allies, but remember that crossing the ocean doesn’t automatically make you a hero. There are housewives in aprons and youngsters in knee pants in Britain who have lived through more high explosives in air raids than many soldiers saw in first-class barrages during the last war.”

March 13, 2024

The History of the Chocolate Chip Cookie – Depression vs WW2

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Dec 5, 2023WWII ration-friendly chocolate chip cookies made with shortening, honey, and maple syrup

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1940sDuring WWII, everyone in the US wanted to send chocolate chip cookies to the boys at the front. With wartime rationing in effect, we get a recipe that doesn’t use butter or sugar, but shortening, honey, and maple syrup instead.

The dough is much softer than the original version, and the cookies spread out a lot more as they bake. They bake up softer than the crunchy originals, with a light pillowy texture. They aren’t as sweet, but still have a really lovely flavor. It kind of reminds me of Raisin Bran, but with chocolate. All in all, I was pleasantly surprised.

Check out the episode to see a side-by-side comparison with the original recipe.

(more…)

February 18, 2024

QotD: British meals – sauces

Here also we may mention the special sauces which are so regularly served with each kind of roast meat as to be almost an integral part of the dish. Hot roast beef is almost invariably served with horseradish sauce, a very hot, rather sweet sauce made of grated horseradish, sugar, vinegar and cream. With roast pork goes apple sauce, which is made of apples stewed with sugar and beaten up into a froth. With mutton or lamb there usually goes mint sauce, which is made of chopped mint, sugar and vinegar. Mutton is frequently eaten with redcurrant jelly, which is also served with hare and with venison. A roast fowl is always accompanied by bread sauce, which is made of the crumb of white bread and milk flavoured with onions, and is always served hot. It will be seen that British sauces have the tendency to be sweet, and some of the pickles that are eaten with cold meat are almost as sweet as jam. The British are great eaters of pickles, partly because the predilection for large joints means that in a British household there is a good deal of cold meat to finish up. In using up scraps of food they are not so imaginative as the peoples of some other countries, and British stews and “made-up dishes” – rissoles and the like – are not particularly distinguished. There are, however, two or three kinds of pie or meat-pudding which are peculiar to Britain and are good enough to be worth mentioning. One is steak-and-kidney pudding, which is made of chopped beef-steak and sheep’s kidney, encased in suet crust and steamed in a basin. Another is toad-in-the-hole, which is made of sausage embedded in a batter of milk, flour and eggs basked in the oven. There is also the humble cottage pie, which is simply minced beef or mutton, flavoured with onions, covered with a layer of mashed potatoes and baked until the potatoes are a nice brown. And finally there is the famous Scottish haggis, in which liver, oatmeal, onions and other ingredients are minced up and cooked inside the stomach of a sheep.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)