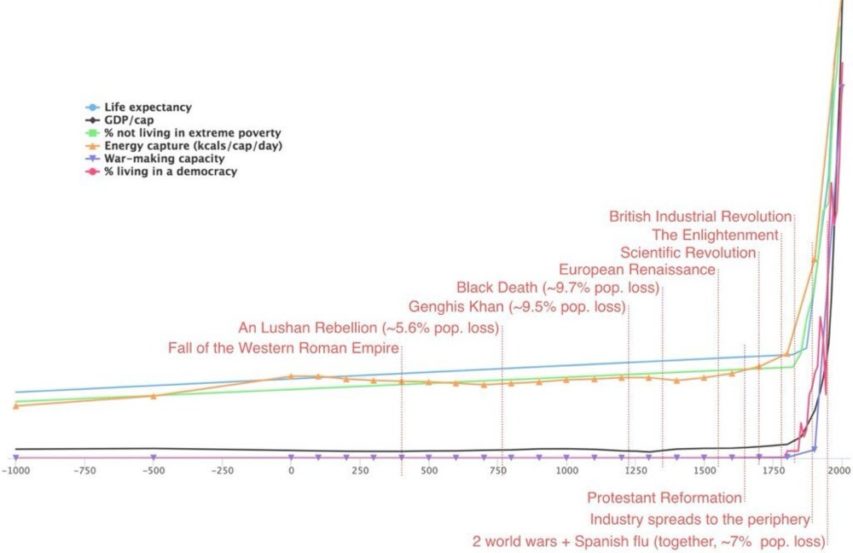

Alyssa Ahlgren ponders the fact that we North Americans take our unprecedented-in-human-history prosperity very much for granted:

I’m sitting in a small coffee shop near Nokomis trying to think of what to write about. I scroll through my newsfeed on my phone looking at the latest headlines of Democratic candidates calling for policies to “fix” the so-called injustices of capitalism. I put my phone down and continue to look around.

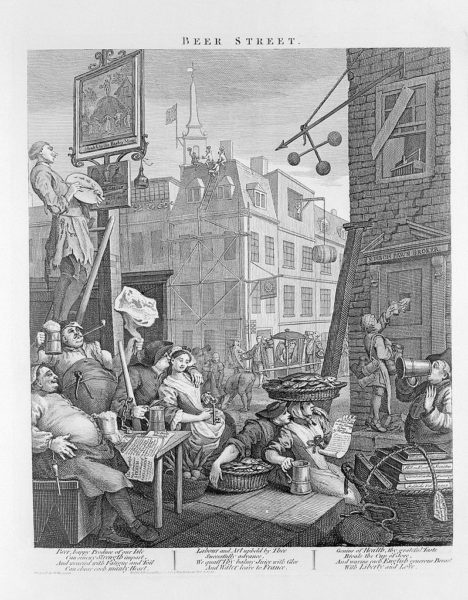

I see people talking freely, working on their MacBooks, ordering food they get in an instant, seeing cars go by outside, and it dawned on me. We live in the most privileged time in the most prosperous nation and we’ve become completely blind to it. Vehicles, food, technology, freedom to associate with whom we choose.

These things are so ingrained in our American way of life we don’t give them a second thought. We are so well off here in the United States that our poverty line begins 31 times above the global average. Thirty. One. Times. Virtually no one in the United States is considered poor by global standards. Yet, in a time where we can order a product off Amazon with one click and have it at our doorstep the next day, we are unappreciative, unsatisfied, and ungrateful.

Our unappreciation is evident as the popularity of socialist policies among my generation continues to grow. Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently said to Newsweek talking about the millennial generation, “An entire generation, which is now becoming one of the largest electorates in America, came of age and never saw American prosperity.”

Never saw American prosperity. Let that sink in. When I first read that statement, I thought to myself, that was quite literally the most entitled and factually illiterate thing I’ve ever heard in my 26 years on this earth. Now, I’m not attributing Miss Ocasio-Cortez’s words to outright dishonesty. I do think she whole-heartedly believes the words she said to be true. Many young people agree with her, which is entirely misguided. My generation is being indoctrinated by a mainstream narrative to actually believe we have never seen prosperity. I know this first hand, I went to college, let’s just say I didn’t have the popular opinion, but I digress.

Let me lay down some universal truths really quick. The United States of America has lifted more people out of abject poverty, spread more freedom and democracy, and has created more innovation in technology and medicine than any other nation in human history. Not only that but our citizenry continually breaks world records with charitable donations, the rags to riches story is not only possible in America but not uncommon, we have the strongest purchasing power on earth, and we encompass 25 percent of the world’s GDP. The list goes on.