Christ taught giving. Giving means taking ones own property and passing it on to someone in need. Nowhere did he advocate taking from others by force and “redistributing” it. He certainly did not advocate taking from others, using what’s taken to fund a huge government bureaucracy, and pass out a pittance of the remainder to the poor (have to justify that bureaucracy somehow).

Nowhere in the Bible is there a passage similar to this:

And I say unto you, take up your sword and shew it to the rich man and say unto him “give to me your wealth that it might care for the poor, lest I smite you to the Earth.”

And when the wealthy man has given up his wealth, take it and pay for a multitude of scribes and pharisees and learned doctors of the law and say unto them, “use this wealth to provide for your hire, but only this, save a pittance thereof and give it unto the poor so that we may noise about this good work and stand in the marketplace speaking loudly of these alms we give.”

And when this is done, say unto the people “Behold, we have cared for the poor. Now give us more of your wealth that we may continue to do so and to do other things.”

And if any dare to resist you, lay your hands upon him and chain him and cast him into a dungeon.

And in all this way shall you show unto the people your mercy and kindness.

When people advocate socialism enforced by government, they are advocating using force to take from some to give to others. Nowhere in his teachings did Christ advocate that. Nowhere.

This is where some people say “but Christ said Render unto Caesar.” Yes. He did. In response to a question intended to trap him. Context matters. Christ had rising popularity among the masses which concerned the Jewish leadership greatly. So they planted the question of whether they should give tribute to Caesar. If Christ had simply said “yes” he would have lost his popular audience and his ministry would have died right there. If he had said “no”, he would likely have been arrested (“we caught him forbidding tribute to Caesar” was one of the charges the Sanhedrin laid against him when handing him over to the Romans for execution). And his ministry would have died right there. Instead, he asked for an example of the tribute money, asked whose picture was on it, and gave his famous answer. And if people followed him in that, the Roman reprisal, destruction of Jerusalem, and diaspora would have occurred before much of Christ’s mission was fairly begun. If you accept his divinity, you have to accept that he knew this and gave the answer that allowed him to complete his mission.

But did “render unto Caesar” mean an endorsement of everything that tax funds were used for? Did he endorse gladiatorial games? Wars of conquest? The capture and importation of slaves? The use of government troops to put down slave revolts? Let’s not be absurd. Just because the Roman government did something with tax monies, or modern governments do something with it, “Render unto Caesar” is not an endorsement of that use.

Government is force, pure and simple. That’s essentially a definition of government: the legitimizing of the use of force. Socialism imposed by government has nothing to do with Christian charity. It is, in fact, very nearly the exact opposite, wearing a mask to confuse the unwary.

David L. Burkhead, “The “Christian Left”, The Writer in Black, 2018-01-08.

March 27, 2020

March 26, 2020

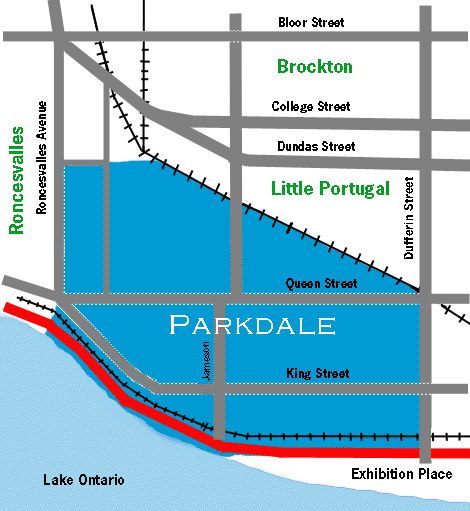

David Warren on the situation in Parkdale

David Warren provides a glimpse of what life is like in the Toronto neighbourhood of Parkdale during the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic:

Is gentle reader bored with pathogens yet? At some point in the proximate future, death will lose its sting. While there are plausible economic reasons for people to return to work, there is also a dark secret. The most restless society since the invention of restlessness cannot cope with “downtime.” This is what gives me my monopoly on Idleness. Without the “events” which help to distinguish one day from another, we will need to start a war.

Had we books, and to have developed the habit of using them, we might read history instead; and even a bit of poetry on the side. But now, at loose ends, we are inspired to do something. Also, please note, the doctrine of original sin. I’m a big fan.

My political dogma has surely been established by now. I am against “doing” anything. Fight for a world in which nothing exciting happens, other than the pursuit of beauty, goodness, and truth. Fight relentlessly — by example.

Here in Parkdale, Toronto’s go-to centre for the criminally insane, there is always entertainment. From my balconata I can spy several half-way houses, and for variety, a Tibetan temple. The streets get quieter every day, especially the throb of the superhighways. It has been softening, as the economy bleeds away; and there are clear days with no contrails in the sky.

The “Green Nude Eel” is being accomplished. Superficially, this might seem like a good thing.

But because Parkdale has been unable to start a war with our bourgeois neighbour — Liberty Village, where the childless young professionals live in sterilized apartment blocks — we have had to look for excitement elsewhere. By calling 9-1-1 frequently, the Vallishortensians (demonym for “Parkdale”) are able to keep the sirens blaring, and little knots of emergency vehicles collecting, to no definable purpose here and there. Due to my Scottish genetic endowment, I follow these skits as I would a taxi-meter: How much have we cost the taxpayers today?

March 20, 2020

QotD: Absolute and relative poverty

… in that historical sense, a GDP per capita of $600 a year. Or the current global one, something like $8,000 (depends upon who is doing the counting a bit for that one). That we’re worrying about $34,000 a year, that this is poverty, is exactly the example we need of how well that American capitalism has worked over those centuries.

That the poor of our nation live better than 90 percent of anyone only 100 years ago, better than anyone at all from more than 200 years ago, shows just how fabulous an economic system it is.

Sure, it’s not perfect, it could do with some revisions here and there, but this system — the rule of law, markets, and capitalism — delivers in the one thing that truly matters: raising the living standards of the people, most especially poor people. Even more, no other economic system has managed this at all.

Tim Worstall, “Appalachia’s woes show the success of American capitalism”, Washington Examiner, 2018-01-09.

March 18, 2020

QotD: The “magic” of capitalism

Warren Buffett has told us that there’s something magical about American capitalism. This isn’t quite true, because other countries have achieved much the same thing. What is true about it is that it is the system itself which has caused the incredible wealth we all enjoy in this modern world. Buffett writes:

In 1776, America set off to unleash human potential by combining market economics, the rule of law and equality of opportunity. This foundation was an act of genius that in only 241 years converted our original villages and prairies into $96 trillion of wealth.

Other places which did much the same thing — that mixture of capitalism, the rule of law and free markets — achieved much the same end. We generally refer to those places as the developed world, while those that didn’t are still the Third World. There is nowhere at all that has become rich, absent some vast natural resource, without adopting this system.

We can show this, too, with the numbers from Angus Madison. The average GDP per capita over history, all countries, all empires, was some $600 a year or so — That’s in today’s dollars, meaning history was, by our standards, abject destitution for everyone. This is also why we use $1.90 a day (at modern American prices) as our measure of global absolute poverty. Because that’s just what the past was and we celebrate when people, a country, a nation, rise above that historical existence.

Tim Worstall, “Appalachia’s woes show the success of American capitalism”, Washington Examiner, 2018-01-09.

March 15, 2020

Those damned unintended consequences

Sarah Hoyt on the differences between intention and the real world:

Unintended consequences are the bane of social engineers. They are why the “Scientific” and centralized method of governance never worked and will never work. (Sorry, guys, it just won’t.)

Part of it is because humans are contrary. Part of is because humans are chaotic. And part of it is because like weather systems, societies are so complex it’s almost impossible to figure out what a push in any given place will cause to happen in another place.

This is why price controls are the craziest of idiocies. They don’t work in the way they’re intended, but oh, they work in practically all the ways they’re not. So, take price controls on rent. All they really do is create a market in which housing is scarce, landlords don’t maintain their property AND the only people who can afford to live in cities that have rent control are the very wealthy.

BUT Sarah, you say, aren’t rent controls supposed to make them affordable. Yeah. All that and the good intentions will allow you to go skating in hell on the fourth of July weekend.

Let’s be real, okay? I saw rent control up close and personal in Portugal. Rents were controlled and landlords were penalized for “not keeping the property up”.

In Portugal at the time, and here too, most of the time from what I’ve seen, the administration of property might be some management company, but that’s not who OWNS the damn thing. The owners are usually people who bought the property so it would support them in old age/lean times.

To begin with, you’re removing these people’s ability to make money off their legitimately owned property. And no, they’re not the plutocrats bernie bros imagine. These are often people just making it by.

Second, people are going to get the money some other way, because the alternative is dying. And people don’t want to die or be destitute. So they’re going to find the money. I have no idea what it is in NYC, etc, but in Portugal? it was “key buying.” Sure, you can rent the house for the controlled price, but you have to make a huge payment upfront to “buy the key.” From what I remember this was on the order of a small house down payment. And if you couldn’t do that, you were stuck getting married and living with your parents. And if you say “greedy landlords” — well, see the other thing you could do was leave the lease in your will. So the landlord didn’t know if they’d ever get control of their property back, and they needed to live off this for x years (estimated length of life.) So, that was an unintended consequence. The kind that keeps surfacing in rent-controlled cities in the US.

The same applies to attempts to “help” the homeless. Part of this, as part of all attempts to “fix” poverty is that the people doing it, usually the result of generations of middle class parents and strives assume the homeless and the poor are people like them.

To an extent, they’re correct. The homeless and the poor are PEOPLE. But culture makes a difference, and culture is often based on class and place of upbringing. And the majority of humanity, judging by the world, might be made to strive but are not natural strivers. Without incentive, most of humanity sits back, relaxes and takes what it’s given.

February 27, 2020

QotD: Clichés of bad travel writing

The poor-but-oh-so-happy sentiment pops up without fail in any crappy travel magazine version of a visit to Myanmar, Laos, or Nepal (and probably any other desperately poor and badly governed country), in which “the people” are always gleeful, generous, and colorful. I’m not exactly sure what it is about being ruled by insane dictators that makes people so damn nice, but here’s an idea: If you’re a Western travel writer, or, say, German tourist, and you’re going to an impoverished country full of hungry people in which you clearly stand out as someone with money to spend, people might be extra nice to you.

Kerry Howley, “But the People Are So Friendly“, Hit and Run, 2005-08-18.

February 7, 2020

QotD: The negative economic and human value of foreign aid

I’d like nothing better than to be proven wrong, but I’m gloomily confident that my prediction of failure will be verified. History and sound economics both warn that foreign aid is far more likely to harm than to help economies.

During the past four decades, Western governments have lavished on Africa nearly a half-trillion dollars in aid. But to no good effect. Everyone agrees that Africans remain desperately poor.

Academic studies confirm aid’s ineffectiveness. In his celebrated 2001 book, The Elusive Quest for Growth, former World Bank economist William Easterly carefully reviews aid’s history and concludes that it is one of abject failure.

Indeed, many studies find that aid harms economies. For example, University of Regina economist Tomi Ovaska, writing in the Cato Journal, finds that “a 1 percent increase in aid as a percent of GDP (gross domestic product) decreased annual real GDP per capita growth by 3.65 percent.”

The reasons for this dismal record should be plain to anyone with a rudimentary understanding of economics. Failure of economies to develop is not because of lack of resources. Instead, it’s because of overbearing and corrupt governments, as well as to the dysfunctional social and cultural institutions that keep such governments in power and that are themselves fostered by such governments.

As long as a country is cursed by a malignant government and dysfunctional institutions, no amount of foreign aid will help it.

Don Boudreaux, “Faulty Band-Aid”, Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, 2005-06-18.

January 21, 2020

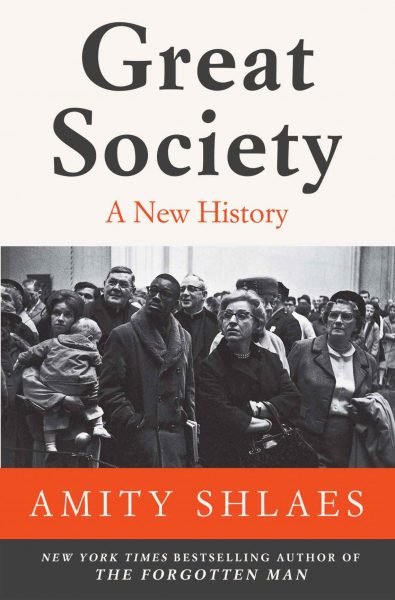

Amity Shlaes’ Great Society: A New History

In City Journal, Edward Short reviews the latest American economic history book by Amity Shlaes:

In Great Society: A New History, Amity Shlaes revisits the welfare programs of the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations to show not only how misguided they were but also what a warning they present to those who wish to resurrect and extend such programs. “The contest between capitalism and socialism is on again,” the author writes in her introduction. Despite the Trump administration’s thriving economy, or perhaps because of it, Democratic Party progressives are calling for new welfare programs even more radical than those advocated in the 1960s by the socialist architect of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, Michael Harrington. In the new schemes for wealth redistribution, student debt relief, socialized medicine, and universal guaranteed income that make up the Democrats’ political platform in 2020, Shlaes rightly sees a recycling of Great Society hobby horses — and she worries that a good portion of the electorate may be taken in by them. “Once again many Americans rate socialism as the generous philosophy,” she observes, and she has written her admirable, sobering study to make sure that readers realize that the “results of our socialism were not generous.”

Reviewing how ungenerous makes for salutary reading. After all, socialism of any stripe, whether in Russia, South America, Europe, or America, has always been an inherently deceitful enterprise. Shales captures the essence of this imposture when she describes one of its manifestations as “Prettifying a political grab by dressing it up as an economic rescue.” In totting up these receipts for deceit, Shlaes has done a genuine public service. […]

On display here are all of Shlaes’s strengths as an author: her clear and unpretentious prose, sound critical judgment, readiness to enter into the thinking of her subjects with sympathy (even when she regards it as mistaken), and, perhaps most impressively, understanding how history can help us fathom what might otherwise be obscure in our own more immediate history.

Accordingly, she describes the influence that Roosevelt’s New Deal had on Johnson, who saw it as a model for maintaining and consolidating his Democratic majorities, as well as focusing his Cabinet’s talents. “The men around Johnson,” Shlaes points out, including Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, Richard Goodwin, and Sargent Shriver, “felt the weight of his faith on them, and strove hard. Vietnam would be sorted out. There would be a Great Society. Poverty would be cured. Blacks of the South would win full citizenship. The Great Society would succeed.” Yet the president’s men could not help asking “by what measures” it would succeed.

Moynihan’s answer to this question is one that still mesmerizes social-engineering elites. The Great Society would be achieved by social science. “Progress begins on social problems when it becomes possible to measure them,” Moynihan declared. Improved quantitative analysis would give the centralized power of planners a new credibility.

Whether Johnson himself ever truly believed in such claims is questionable. When aides asked the exuberant Texan what he thought of the risks of going forward with his wildly ambitious program, his reply epitomized the hubris at the heart of his Great Society: “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

January 2, 2020

The 2010s … the best decade (so far) in human history

Matt Ridley explains why, despite all the doom and gloom in the daily headlines, the last ten years have been the best by almost any measure:

Let nobody tell you that the second decade of the 21st century has been a bad time. We are living through the greatest improvement in human living standards in history. Extreme poverty has fallen below 10 per cent of the world’s population for the first time. It was 60 per cent when I was born. Global inequality has been plunging as Africa and Asia experience faster economic growth than Europe and North America; child mortality has fallen to record low levels; famine virtually went extinct; malaria, polio and heart disease are all in decline.

Little of this made the news, because good news is no news. But I’ve been watching it all closely. Ever since I wrote The Rational Optimist in 2010, I’ve been faced with “what about …” questions: what about the great recession, the euro crisis, Syria, Ukraine, Donald Trump? How can I possibly say that things are getting better, given all that? The answer is: because bad things happen while the world still gets better. Yet get better it does, and it has done so over the course of this decade at a rate that has astonished even starry-eyed me.

Perhaps one of the least fashionable predictions I made nine years ago was that “the ecological footprint of human activity is probably shrinking” and “we are getting more sustainable, not less, in the way we use the planet”. That is to say: our population and economy would grow, but we’d learn how to reduce what we take from the planet. And so it has proved. An MIT scientist, Andrew McAfee, recently documented this in a book called More from Less, showing how some nations are beginning to use less stuff: less metal, less water, less land. Not just in proportion to productivity: less stuff overall.

This does not quite fit with what the Extinction Rebellion lot are telling us. But the next time you hear Sir David Attenborough say: “Anyone who thinks that you can have infinite growth on a planet with finite resources is either a madman or an economist”, ask him this: “But what if economic growth means using less stuff, not more?” For example, a normal drink can today contains 13 grams of aluminium, much of it recycled. In 1959, it contained 85 grams. Substituting the former for the latter is a contribution to economic growth, but it reduces the resources consumed per drink.

As for Britain, our consumption of “stuff” probably peaked around the turn of the century — an achievement that has gone almost entirely unnoticed. But the evidence is there. In 2011 Chris Goodall, an investor in electric vehicles, published research showing that the UK was now using not just relatively less “stuff” every year, but absolutely less. Events have since vindicated his thesis. The quantity of all resources consumed per person in Britain (domestic extraction of biomass, metals, minerals and fossil fuels, plus imports minus exports) fell by a third between 2000 and 2017, from 12.5 tonnes to 8.5 tonnes. That’s a faster decline than the increase in the number of people, so it means fewer resources consumed overall.

H/T to Damian Penny for the link.

November 27, 2019

The “Gentrification” debate

In Quillette, Coleman Hughes explains the furor over gentrification in many big American cities:

“Shoreditch Graffiti” by Kit-Kat is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The word “gentrification” was coined in 1964 to describe the influx of wealthy newcomers into low-income inner-city neighborhoods, resulting in rising property values, changes in neighborhood culture, and displacement of original residents. Though gentrification predates the modern era, it has only become the target of criticism in recent decades, as cities like Washington, D.C., Atlanta, and Boston have witnessed rapid transformations. Opponents of gentrification have ranged from residents directly affected by it to wealthy college students directly responsible for it, as well as prominent Democrats such as Bernie Sanders, Cory Booker, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Critics of gentrification give two main reasons for their opposition: (1) wealthy newcomers drive up monthly rents, thereby displacing original residents; and (2) rapid change to neighborhood culture represents an injustice to original residents. Both critiques are magnified by the presumed skin color of the gentrifiers and the gentrified, who tend to be white and black or Hispanic, respectively.

Though such critiques may seem reasonable at first glance, neither of them survive scrutiny. Not only is gentrification harmless, it’s actually beneficial. Indeed, for reasons I will lay out, it’s exactly the kind of thing that progressives should support.

Let’s begin with the charge that gentrification displaces original residents. Two economists used data from the 2000 U.S. Census and the 2010-2014 American Community Survey to track individual outcomes for all residents of “gentrifiable” — or low-income inner-city — neighborhoods in America’s one hundred largest metropolitan areas. The largest study of its kind, it divided residents of gentrifiable neighborhoods into two categories based on educational attainment. Their findings refute the displacement narrative conclusively.

[…]

On the whole, progressives ought to love gentrification. It makes black inner-city homeowners wealthier. Among less-educated homeowners — who are majority non-white and comprise over a quarter of the total population in gentrifiable neighborhoods — those who remained in gentrified neighborhoods saw a $15,000 increase in the value of their homes due to gentrification. Among more-educated homeowners — who are also majority non-white — those who remained saw a $20,000 increase in property value.

What’s more, gentrification breaks up concentrated poverty and reduces residential segregation. Progressives have frequently observed that poor blacks are more likely to live in concentrated poverty than poor whites. As a result, they lose out on the advantages that come with living in a mixed-income neighborhood. Gentrification helps solve this problem. Moreover, progressives often observe that residential segregation remains pervasive half a century after the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Gentrification helps solve that problem too.

November 4, 2019

QotD: Ludwig von Mises explains the fall of the western Roman empire

Knowledge of the effects of government interference with market prices makes us comprehend the economic causes of a momentous historical event, the decline of ancient civilization.

[…]

The Roman Empire in the second century, the age of the Antonines, the “good” emperors, had reached a high stage of the social division of labour and of interregional commerce. Several metropolitan centres, a considerable number of middle-sized towns, and many small towns were the seats of a refined civilisation […]. There was an extensive trade between the various regions of the vast empire. Not only in the processing industries, but also in agriculture there was a tendency toward further specialization. The various parts of the empire were no longer economically self-sufficient. They were interdependent.

What brought about the decline of the empire and the decay of its civilization was the disintegration of this economic interconnectedness, not the barbarian invasions. The alien aggressors merely took advantage of an opportunity which the internal weakness of the empire offered to them. From a military point of view the tribes which invaded the empire in the fourth and fifth centuries were not more formidable than the armies which the legions had easily defeated in earlier times. But the empire had changed. Its economic and social structure was already medieval […]

[I]n the political troubles of the third and fourth centuries the emperors resorted to currency debasement. With the system of maximum prices the practice of debasement completely paralysed both the production and the marketing of the vital foodstuffs and disintegrated society’s economic organisation. The more eagerness the authorities displayed in enforcing the maximum prices, the more desperate became the conditions of the urban masses dependent on the purchase of food. Commerce in grain and other necessities vanished altogether. To avoid starving, people deserted the cities, settled on the countryside, and tried to grow grain, oil, wine, and other necessities for themselves.

Ludwig von Mises, Human Action, 1949.

October 21, 2019

September 3, 2019

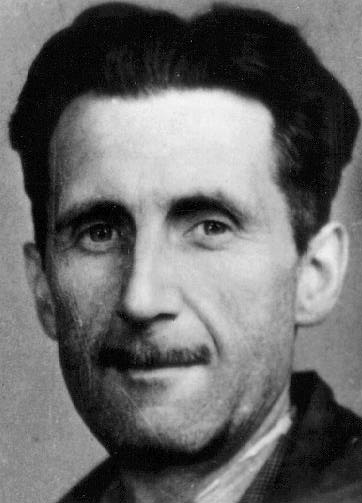

QotD: Fencing out the London poor

I see that the railings are returning — only wooden ones, it is true, but still railings — in one London square after another. So the lawful denizens of the squares can make use of their treasured keys again, and the children of the poor can be kept out.When the railings round the parks and squares were removed, the object was partly to accumulate scrap-iron, but the removal was also felt to be a democratic gesture. Many more green spaces were now open to the public, and you could stay in the parks till all hours instead of being hounded out at closing times by grim-faced keepers. It was also discovered that these railings were not only unnecessary but hideously ugly. The parks were improved out of recognition by being laid open, acquiring a friendly, almost rural look that they had never had before. And had the railings vanished permanently, another improvement would probably have followed. The dreary shrubberies of laurel and privet — plants not suited to England and always dusty, at any rate in London — would probably have been grubbed up and replaced by flower beds. Like the railings, they were merely put there to keep the populace out. However, the higher-ups managed to avert this reform, like so many others, and everywhere the wooden palisades are going up, regardless of the wastage of labour and timber.

George Orwell, “As I Please” Tribune, 1944-08-04.

July 6, 2019

Putting global worker pay into perspective

Tim Worstall explains why the headline-friendly numbers in a recent ILO report are nothing to be surprised at:

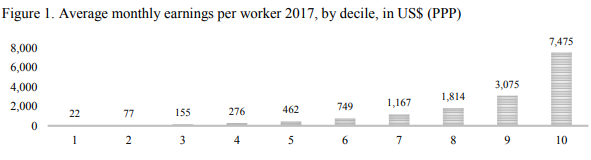

“Nearly half of all global pay is scooped up by only 10% of workers, according to the International Labour Organization, while the lowest-paid 50% receive only 6.4%.

“The lowest-paid 20% – about 650 million workers – get less than 1% of total pay, a figure that has barely moved in 13 years, ILO analysis found. It used labour income figures from 189 countries between 2004 and 2017, the latest available data.

“A worker in the top 10% receives $7,445 a month (£5,866), while a worker in the bottom 10% gets only $22. The average pay of the bottom half of the world’s workers is $198 a month.”

[…]

The explanation? To be in the top 10% of the global pay distribution you need to be making around and about minimum wage in one of the rich countries. Via another calculation route, perhaps median income in those rich countries. No, that £5,800 is the average of all the top 10%.

Note that this is in USD. About £2,000 a month puts you in the second decile, that’s about UK median income of 24,000 a year.

And as it happens about 20% of the people around the world are in one of the already rich countries. So, above median in a rich country and we’re there. Our definition of rich here not quite extending as far as all of the OECD countries even. Western Europe – plus offshoots like Oz and NZ, North America, Japan, S. Korea and, well, there’s not much else. Sure, it’s not exactly 10% of the people there but it’s not hugely off either.

So, what is it that these places have in common? They’ve been largely free market, largely capitalist, economies for more than a few decades. The most recent arrival, S. Korea, only just managing that few decades. It is also true that nowhere that hasn’t been such is in that listing. It’s even true that nowhere that is such hasn’t made it – not that we’d go to the wall for that last insistence although it’s difficult to think of places that breach that condition.