I have always been deeply suspicious of the word “responsibility”. It has again and again sounded like someone else telling me that I must do what he wants me to do rather than what I want to do. If he is paying my wages, then fair enough. But if he is explaining why I should vote for him, and support everything he does once he has got the job he is seeking, not so fair.

The sort of thing I mean is when a British Conservative Party politician says, perhaps to a room full of people who, like me, take the idea of personal liberty very seriously: Yes, I believe, passionately, in personal liberty. The politician maybe then expands upon this idea, often with regard to how commercial life works far better if people engaged in commerce are able to make their own decisions about which projects they will undertake and which risks they will walk towards and which risks they will avoid. If business is all coerced, it won’t be nearly so beneficial. We will all get poorer. Yay freedom.

But.

But … “responsibility”. We should all have freedom, yes, but we also have, or should have, “responsibility”. Sometimes there then follows a list of things that we should do or should refrain from doing, for each of which alleged responsibility there is a law which he favours and which we must obey. At other times, such a list is merely implied. So, freedom, but not freedom.

The problem with politicians talking about responsibility is that their particular concern is and should be the law, law being organised compulsion. And too often, their talk of responsibility serves only to drag into prominence yet more laws about what people must and must not do with their lives. But because the word “responsibility” sounds so virtuous, this list of anti-freedom laws becomes hard to argue against, even inside one’s own head. Am I opposed to “responsibility”? Increasingly, I have found myself saying: To hell with it. Yes.

I have often been similarly resistant to the language of Christianity, of the sort that dominates what is being said in churches around the world today. How many times in history have acts of tyranny been justified by the tyrant saying something like: We must all bear our crosses in life, and here, this cross is yours. “God is on my side. Obey my orders.” The truth about the potential of life to inflict pain becomes the excuse to inflict further pain.

Brian Micklethwait, “Jordan Peterson on responsibility – and on why it is important that he is not a politician”, Samizdata, 2018-03-30.

August 5, 2020

QotD: Responsibility

June 25, 2020

Capitalism and slavery

In Quillette, Matthew Lesh explains why glib claims that slavery was somehow “essential” to early capitalism or that slavery was the cause of western wealth just don’t hold up to any historical scrutiny:

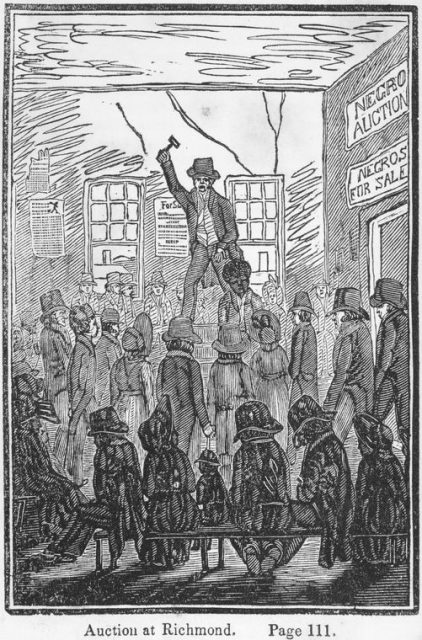

Auction at Richmond. (1834)

“Five hundred thousand strokes for freedom; a series of anti-slavery tracts, of which half a million are now first issued by the friends of the Negro” by Wilson Armistead and “Picture of slavery in the United States of America” by George Bourne.

New York Public Library via Wikimedia Commons.

It has become a common trope that slavery and the slave trade is responsible for the industrial revolution, if not our entire modern prosperity. Slavery is often called capitalism’s “dark side.” A recent column in the Guardian claimed the slave trade “heralded the age of capitalism” and Guardian columnist George Monbiot said on Twitter: “The more we discover about our own history, the less the ‘trade’ on which Britain built its wealth looks like exchange, and the more it looks like looting. It meant extracting stolen resources and the products of slavery, debt bondage and land theft from other nations.” The same line has been taken by London Mayor Sadiq Khan, who tweeted: “It’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade.”

But what did the “father of modern economics,” Adam Smith, actually think about slavery? And is it responsible for our modern prosperity?

Adam Smith argued not only that slavery was morally reprehensible, but that it causes economic self-harm. He provided economic and moral ammunition for the abolitionist movement that came to fruition after his death in 1790. Smith was pessimistic about the potential for full abolition, but he was on the side of the angels.

Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, contains perhaps the best known economic critique of slavery. Smith argued that free individuals work harder and invest in the improvement of land, motivated by their interest in earning a higher income, than slaves. Smith refers to ancient Italy, where the cultivation of corn degraded under slavery. The cost of slavery is “in the end the dearest of any,” Smith writes.

His thinking about slavery can be traced further back. In the Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms, delivered in 1763 long before Britain’s abolitionist movement was formalised, Smith writes:

Slaves cultivate only for themselves; the surplus goes to the master, and therefore they are careless about cultivating the ground to the best advantage. A free man keeps as his own whatever is above his rent, and therefore has a motive to industry.

Smith describes how serfs in Western Europe — in feudal relationships with lords — were progressively transformed into free tenants as they acquired cattle and tools. Harvests were more evenly divided between landlord and tenant to encourage better use of land, and tenants eventually progressed to simply giving the landlord a sum for lease. As government became more established, the influence of lords over the lives of tenants was also loosened.

Capitalism was, as Marx described, the next stage in human development after feudal slave relations. Smith’s commercial society is in direct opposition to a slave society. Smith, at his core, is an advocate for individuals being free to specialize and trade, including to trade their labor. Everyone acting with regard to their “own interest,” not because of coercion, creates general prosperity.

Smith’s case against slavery is proven by history: The huge uptick in human prosperity came largely after the end of feudal relations and the abolition of slavery and the slave trade. We are many magnitudes richer than when lords held slaves, or even chattel slavery proliferated in the Americas. The setting free of humanity led to extraordinary innovation and entrepreneurialism. This is only possible, as Smith argued, when individuals can benefit from the fruits of their own labor (slaves cannot hold property in their own name, and hence cannot trade or choose to specialise).

We didn’t become rich because a few hundred years ago people toiled on farms in awful conditions. In fact, the opposite. “It was precisely the replacement of human muscle power with that of steam and machines which did away with the vileness of chattel slavery and forced labor,” Tim Worstall has explained.

June 20, 2020

History-Makers: Confucius

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 19 Jun 2020Welcome to the challenge run of History-Makers, where I attempt to give insightful historical context to someone whose backstory is almost entirely blank.

SOURCES & Further Reading: Confucius: A Very Short Introduction by Gardner, China: A History by Keay, The Analects of Confucius, The Mencius.

This video was edited by Sophia Ricciardi AKA “Indigo”. https://www.sophiakricci.com/

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

QotD: Morality and the government

If an action is immoral for me and you, it is also immoral for others, including those who constitute the government. Election to public office is not a licence to lie, defraud, extort, rob, kidnap, or murder. Those who believe that government officials, employees, and contractors may morally do what other individuals may not do are morally bankrupt. The government has the power to act immorally — and does so as its standard operating procedure — but power and just right are completely different things. To affirm that might makes right in a moral sense is to affirm that one has simply chosen to abandon all pretense of taking morality seriously.

Gaze upon the members of Congress, the president and his lieutenants, the justices of the Supreme Court, and the leading figures of the government bureaucracies. As I do so, I cannot help but wonder: Who are these people? I am not personally acquainted with a single one of them; they are complete strangers to me. I have not contracted with them for the provision of any services, nor have I agreed to support them financially. Why then do these strangers presume to dictate to me what I must do and not do, and to threaten me with violence if I do not obey? They might as well be alien invaders from outer space.

Robert Higgs, “A Straightforward View of Morality and the Government”, The Beacon, 2018-03-06.

June 18, 2020

The fall of olde timey “liberalism”

David Warren on the way “liberalism” was dissected, consumed, digested, and excreted by progressivism:

From different angles, from Tocqueville to Schumpeter to a thousand reporters on the ground, it has been observed that liberalism defeats itself. I mean by this real liberalism, not the poison candy version that is offered to children by our academic Left. The real thing celebrates liberty as the central political good, and equality of opportunity versus equality of result. It frees up economies and societies, by cancelling hidebound rules and regulations. When much younger and under the influence of my father and his war-veteran generation (his was World War II), I considered myself a “liberal,” for views that activist mobs would now consider to be deeply “conservative,” or as they say, “fascist.”

Opposition to totalitarianism was a key to that generation. They weren’t shy about using arms. A true liberal was an enthusiast for the War in Vietnam, and other global initiatives. Liberals were “open society” in an explicitly anti-communist, 1950s way. They loved “civil rights,” and opposed the Nanny State, although incoherently. They wished to accommodate the women’s movement. Their instinctive suspicion of social programmes, and revulsion for “ideology,” were slipping away; or had already slipped, to a longer historical view.

To be tediously economic, they were intoxicated by the view that, “now we are rich we can afford to have some fun.” They had long been bored with the absolute moral judgements that their ancestors (to whom neither divorce nor contraception were thinkable) took for granted — based on a Protestant Christianity that had been abandoned by sophisticated intellectuals a century before. “Church versus State” was no longer an issue, and because it wasn’t, morality became a statist “construct,” even without action from the Marxists.

When Ross Douthat writes a book on “decadence,” he is treating it as a temporal trend: something that comes and goes through the decades. His arguments are themselves decadent: something for the chattering classes to play, in the spirit of badminton. It is a topic for upmarket wit; no horror lurks beneath it. The old Gibbonesque “decline and fall” narrative has evaporated with classical culture, and been replaced by a dry happyface from which the wrinkles of serious history are botoxed. The “whig view of history” survives, but only by cliché.

What isn’t defended, is soon killed off, in nature but also in metaphysics. Leftism flourishes today, not because it has won any argument, but by eating everything on the liberal side. Even the word, “liberal,” went down with a soft burp. It now represents the denial, or reversal, of everything that liberals once stood for. Gentle reader may prove this to himself, by reading old magazines.

June 11, 2020

QotD: Equal rights

We must separate the moral dimensions of a subject from the empirical questions surrounding it. For example, on the radioactive issue of sex (or gender) differences in cognitive abilities, there is the empirical question of whether or how men and women diverge in certain tasks, and then there is the moral question of how men and women should be treated. Empirically, there is much evidence that in some tasks women excel over men, and in other tasks, men excel over women. For example, women are more dexterous while men are better at throwing; women are superior in visual memory whereas men are better at mentally rotating shapes; women are better at mathematical calculation while men are better at mathematical problem-solving; in terms of overall general intelligence (g), however, there is no gender difference. Morally, however, none of this matters. We should support women’s rights regardless of any physical or cognitive differences between the sexes. To yoke one’s moral evaluation to empirical questions like this is a big mistake; worse is to assume that this is what people always do and therefore we must suppress any empirical evidence that there are differences, as this will only tilt people’s moral judgments toward empirical outcomes.

This reminds me of the debate in the late 1980s through mid-1990s about whether homosexuality was nature or nurture, something you were born to be or a lifestyle choice. Conservatives and Christians argued for the “choice” position and this led to efforts to “convert” gays to straight (or “pray the gay away”) because something that is learned can be unlearned. This led the gay community and supporters thereof to argue for the “born this way” position. The cumulative evidence from multiple lines of inquiry led to the nature position more than that of nurture, but this was another example of confusing the empirical question of the origin of homosexuality with the moral question of the rights of gays and lesbians (today the LGBTQ community). It should go without saying — but unfortunately in these times it must be said again and again — it doesn’t matter what the origins of homosexuality turn out to be, gays and lesbians and everyone else in the LGBTQ community are entitled to the same rights and privileges as everyone else protected by the constitution of their nation (and those nations that have yet to extend legal rights to gays and lesbians need to change their constitutions).

Michael Shermer, interviewed by Claire Lehmann, “The Skeptical Optimist: Interview with Michael Shermer”, Quillette, 2018-02-24.

April 30, 2020

QotD: Nietzsche’s criticism of Christianity (and Judaism)

It is Nietzsche’s chief thesis that most of the so-called Christian morality of today is an inheritance from the Jews, and that it is quite as much out of harmony with the needs of our race and time as the Mosaic law which prohibits the eating of oysters, clams, swine, hares, swans, terrapin and snails, but allows the eating of locusts, beetles and grasshoppers (Leviticus, XI, 4-30). Christianity, true enough, did not take over the Mosaic code en bloc. It rejected all these dietary laws, and it also rejected all the laws regarding sacrifices and most of those dealing with family relations. But it absorbed unchanged the ethical theory that had grown up among the Jews during the period of their decline — the theory, to wit, of humility, of forbearance, of non-resistance. This theory, as Nietzsche shows, was the fruit of that decline. The Jews of David’s day were not gentle. On the contrary, they were pugnacious and strong, and the bold assertiveness that seemed their best protection against the relatively weak peoples surrounding them was visualized in a mighty and thunderous Jehovah, a god of wrath and destruction, a divine Kaiser. But as their strength decreased and their enemies grew in power they were gradually forced into a more conciliatory policy. What they couldn’t get by force they had to get by a show of complaisance and gentleness — and the result was the renunciatory morality of the century or two preceding the birth of Christ, the turn-the-other-cheek morality which Christ erected into a definite system, the “slave-morality” against which Nietzsche whooped and railed nearly two thousand years afterward.

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

April 26, 2020

“If it saves just one life…”

Hector Drummond illustrates the moral failure of falling back on the “if it saves just one life” trope as a justification for any and all restrictions on free people:

Let me ask you a question. Would you give up your job, your savings, your kids’ economic future, your pension, your parents’ current pension, your house, and your mental health, if I told you that doing so may possibly extend my old, sick grandfather’s life by a year or two? I don’t suppose you’d be too keen, would you? In fact, even the most mild-mannered of people is likely to get angry at the sheer effrontery of such a request.

What if I told the world the same thing? What if I told the world that if everyone in every country gave up their wordly possessions, and spent the rest of their lives in grinding poverty, then it’s possible that my grandfather might get to see Christmas? And suppose that there was some bare plausibility to this, based on a computer model developed by scientists at Imperial College. What do you think the world is likely to say to me? The polite response would be, “Sorry to hear about your grandfather, but we’re not going to do this”. The less polite response would be more like … well, just incredulous laughter, and slammed doors.

The reason I bring up these hypothetical scenarios, though, is that all over social media we are hearing about the Covid-19 lockdown being “worth it if it saves just one life”. But would the people saying this really be willing to give up, say, their own house, car and possessions and teenage daughter to someone who is suicidally depressed over their lack of prospects in life? No. Would they be prepared to serve ten years in jail if it saved the life of someone at risk of being killed by gangsters? No. Would they be happy with having the government forcibly remove a kidney from them to extend the life of someone with failing kidneys? No. Economic ruin and loss of liberty is not something we generally regard as a fair trade for a stranger’s life. Generally even the bleeding hearts among us will say, and rightfully so, “I’m sorry for this person, but they are not entitled to this, and I will not damage my life to any great extent for them”. Charitable donations are one thing. So is volunteer service. But that’s it.

Another thing I am seeing is people who say, “Anything is worth it if it saves lives”. Anything? Really? Shall we ban alcohol then? Because some people die from alcohol. Cars? Paracetamol? Steak knives? Shall we ban mobile phones, because terrorists might use them to communicate with? Shall we lock up for life anyone convicted of a minor juvenile crime, in case they turn out to be a killer? The whole idea is too ridiculous for words, yet all over the world there are fearful people hiding in their homes and posting such thoughts. It is one thing to feel sorry for them, but their stupid ideas shouldn’t pass unchallenged.

April 16, 2020

QotD: Nietzsche’s ideas

… an accurate and intelligent account of Nietzsche’s ideas, by one who has studied them and understands them, is, as Mawruss Perlmutter would say, yet another thing again. Seek in What Nietzsche Taught, by Willard H. Wright, and you will find it. Here in the midst of the current obfuscation, are the plain facts, set down by one who knows them. Wright has simply taken the eighteen volumes of the Nietzsche canon and reduced each of them to a chapter. All of the steps in Nietzsche’s arguments are jumped; there is no report of his frequent disputing with himself; one gets only his conclusions. But Wright has arranged these conclusions so artfully and with so keen a comprehension of all that stands behind them that they fall into logical and ordered chains, and are thus easily intelligible, not only in themselves, but also in their interrelations. The book is incomparably more useful than any other Nietzsche summary that I know. It does not, of course, exhaust Nietzsche, for some of the philosopher’s most interesting work appears in his arguments rather than in his conclusions, but it at least gives a straightforward and coherent account of his principal ideas, and the reader who has gone through it carefully will be quite ready for the Nietzsche books themselves.

These principal ideas all go back to two, the which may be stated as follows:

- Every system of morality has its origin in an experience of utility. A race, finding that a certain action works for its security and betterment, calls that action good; and, finding that a certain other action works to its peril, it calls that other action bad. Once it has arrived at these valuations it seeks to make them permanent and inviolable by crediting them to its gods.

- The menace of every moral system lies in the fact that, by reason of the supernatural authority thus put behind it, it tends to remain substantially unchanged long after the conditions which gave rise to it have been supplanted by different, and often diametrically antagonistic conditions.

In other words, systems of morality almost always outlive their usefulness, simply because the gods upon whose authority they are grounded are hard to get rid of. Among gods, as among office-holders, few die and none resign. Thus it happens that the Jews of today, if they remain true to the faith of their fathers, are oppressed by a code of dietary and other sumptuary laws — i.e., a system of domestic morality — which has long since ceased to be of any appreciable value, or even of any appreciable meaning, to them. It was, perhaps, an actual as well as a statutory immorality for a Jew of ancient Palestine to eat shell-fish, for the shell-fish of the region he lived in were scarecly fit for human food, and so he endangered his own life and worked damage to the community of which he was a part when he ate them. But these considerations do not appear in the United Sates of today. It is no more imprudent for an American Jew to eat shell-fish than it is for him to eat süaut;ss-und-sauer. His law, however, remains unchanged, and his immemorial God of Hosts stands behind it, and so, if he would be counted a faithful Jew, he must obey it. It is not until he definitely abandons his old god for some modern and intelligible god that he ventures upon disobedience. Find me a Jew eating oyster fritters and I will show you a Jew who has begun to doubt very seriously that the Creator actually held the conversation with Moses described in the ninteenth and subsequent chapters of the Book of Exodus.

H.L. Mencken, “Transvaluation of Morals”, The Smart Set, 1915-03.

February 22, 2020

February 17, 2020

QotD: Hitchens’ rule of morality

Whenever I heard some bigmouth in Washington or the Christian heartland banging on about the evils of sodomy or whatever, I mentally enter his name in my notebook and contentedly set my watch. Sooner rather than later, he will be discovered down on his weary and well-worn old knees in some dreary motel or latrine, with an expired Visa card, having tried to pay well over the odds to be peed upon by some Apache transvestite.

Christopher Hitchens, quoted by Douglas Murray in “Beware the creepy male feminist: ‘White knights’ like Robert De Niro often turn out to be less than chivalrous”, Unherd, 2019-11-15.

December 11, 2019

November 30, 2019

Toynbee’s warning

In the National Post, Barbara Kay wonders if conservative democracy can shore up the civilizational boundaries that liberal democracy has abandoned:

The Course of Empire – Destruction by Thomas Cole, 1836.

From the New York Historical Society collection via Wikimedia Commons.

The historian Arnold Toynbee warned that “civilizations die from suicide, not by murder.” He said they begin to disintegrate when they abandon moral law and yield to their impulses, which in turn brings about a state of passivity, a sense that there is no point in resisting incoming waves of foreigners driven by confidence and purpose.

Since Toynbee, other writers, notably James Burnham in his influential 1964 essay, “Suicide of the West: An essay on the Meaning and Destiny of Liberalism”, have picked up on the theme. In every case in which the word “suicide” features, the root cause comes down to the effects of a universalist liberal democracy over time. These observers are not trading in fear-mongering for its own sake. We must pay respectful attention to their warnings.

Liberal democracy is, broadly speaking, a political doctrine consecrated to the belief that reason, universally accessible and everywhere the same, can by itself create the conditions for enlightened progress in human affairs.

With social justice as the end and social transformation as the means, liberals are not perturbed by the erosion of Christianity, the traditional family and the cultural particularism such transformation requires. The instinct to jettison cultural babies in order to refresh our cultural bathwater is a feature, not a bug, of liberal democracy.

Conservatives, even those who don’t embrace social conservatism, view the crumbling of these building blocks of civilization with anxiety and fear. Their view is that reason alone, without spiritual ballast and deference to the traditions that created our civilization, can produce social instability and even violence. Nobody considered himself more reasonable than Vladimir Lenin. Nobody considers herself more reasonable than a minister of sport who conflates subjective gender identification with biological sex.

Conservatives’ fears are driving the nationalist/nativist counter-movement liberals view with disgust and anger. Conservatives find it difficult to get an unbiased hearing in the prevailing progressive zeitgeist. Liberals have been successful in linking nationalism with history’s most odious incarnations of racism and imperialism in the popular imagination, while ignoring the equally tragic history of internationalist movements, because Marxist utopianism casts a spell they find irresistible.

So in the matter of immigration, for example, liberals are not concerned by mass immigration from countries with different religious and cultural traditions, because they rely on the universal appeal of liberal principles to even out the initial wrinkles. Conservatives regard these different traditions as deeply entrenched and likely to be negatively transformative to our own culture. They are inclined to impose strictures that encourage integration into, along with recognition of, our own culture’s dominant status. Far from being racist, conservatives view this precaution as a hedge against the kind of inter-cultural tensions spilling over into expressed hatreds that are presently roiling Europe. But as we saw in the last election, even the mildest criticism of mass immigration is the kiss of death to a politician.

Recently, I posted a Quote of the Day from Sarah Hoyt that emphasized the persistence of culture, which is a warning to those who think unlimited immigration from other cultures won’t have negative impacts on the receiving culture:

Societies don’t work that way. Culture doesn’t work that way. In fact culture is so persistent, so stubborn, it leads people to think it’s genetic. (It’s not. A baby taken at birth to another culture will not behave as his culture of origin.) It changes, sure, through invasions and take overs, but so slowly that bits of older cultures and ideas stay embedded in the new culture. It has been noted that the communist rulers of Russia partook a good bit of the Tsarist regime, because the culture of the people was the same and that came through. (They just dialed up the atrocities and lowered the functionality because their ideology was dysfunctional. They blame their failure on Russia itself, but considering how communism does around the world, I’ll say to the extent countries survive it’s because of the underlying culture.)

August 27, 2019

QotD: Salvador Dali and the “benefit of clergy”

Now, if you showed this book, with its illustrations, to Lord Elton, to Mr. Alfred Noyes, to The Times leader writers who exult over the “eclipse of the highbrow” — in fact, to any “sensible” art-hating English person — it is easy to imagine what kind of response you would get. They would flatly refuse to see any merit in Dali whatever. Such people are not only unable to admit that what is morally degraded can be aesthetically right, but their real demand of every artist is that he shall pat them on the back and tell them that thought is unnecessary. And they can be especially dangerous at a time like the present, when the Ministry of Information and the British Council put power into their hands. For their impulse is not only to crush every new talent as it appears, but to castrate the past as well. Witness the renewed highbrow-baiting that is now going on in this country and America, with its outcry not only against Joyce, Proust and Lawrence, but even against T. S. Eliot.

But if you talk to the kind of person who can see Dali’s merits, the response that you get is not as a rule very much better. If you say that Dali, though a brilliant draughtsman, is a dirty little scoundrel, you are looked upon as a savage. If you say that you don’t like rotting corpses, and that people who do like rotting corpses are mentally diseased, it is assumed that you lack the aesthetic sense. Since Mannequin rotting in a taxicab is a good composition. And between these two fallacies there is no middle position, but we seldom hear much about it. On the one side Kulturbolschevismus: on the other (though the phrase itself is out of fashion) “Art for Art’s sake.” Obscenity is a very difficult question to discuss honestly. People are too frightened either of seeming to be shocked or of seeming not to be shocked, to be able to define the relationship between art and morals.

It will be seen that what the defenders of Dali are claiming is a kind of benefit of clergy. The artist is to be exempt from the moral laws that are binding on ordinary people. Just pronounce the magic word “Art”, and everything is O.K.: kicking little girls in the head is O.K.; even a film like L’Age d’Or* is O.K. It is also O.K. that Dali should batten on France for years and then scuttle off like rat as soon as France is in danger. So long as you can paint well enough to pass the test, all shall be forgiven you.

One can see how false this is if one extends it to cover ordinary crime. In an age like our own, when the artist is an altogether exceptional person, he must be allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility, just as a pregnant woman is. Still, no one would say that a pregnant woman should be allowed to commit murder, nor would anyone make such a claim for the artist, however gifted. If Shakespeare returned to the earth to-morrow, and if it were found that his favourite recreation was raping little girls in railway carriages, we should not tell him to go ahead with it on the ground that he might write another King Lear. And, after all, the worst crimes are not always the punishable ones. By encouraging necrophilic reveries one probably does quite as much harm as by, say, picking pockets at the races. One ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dali is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being. The one does not invalidate or, in a sense, affect the other. The first thing that we demand of a wall is that it shall stand up. If it stands up, it is a good wall, and the question of what purpose it serves is separable from that. And yet even the best wall in the world deserves to be pulled down if it surrounds a concentration camp. In the same way it should be possible to say, “This is a good book or a good picture, and it ought to be burned by the public hangman.” Unless one can say that, at least in imagination, one is shirking the implications of the fact that an artist is also a citizen and a human being.

* Dali mentions L’Age d’Or and adds that its first public showing was broken up by hooligans, but he does not say in detail what it was about. According to Henry Miller’s account of it, it showed among other things some fairly detailed shots of a woman defecating.

George Orwell, “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali”, Saturday Book for 1944, 1944.