The past has always interested me more than the future. This backward-looking tendency has only been reinforced by reaching, somewhat unexpectedly, the age of 70. I can’t say that I don’t feel my age because I don’t know what feeling any particular age is like — but one repeatedly hears that 60 is the new 40, 70 is the new 50, and so on; certainly, the human aging process has slowed since I was born. When I look at photos of people who were 50 in the year of my birth, 1949, they look much older and more worn-out than do 50-year-olds now; and if I had lived only to my life expectancy at birth, I would be dead these last four years.

So progress must have occurred in the intervening time, despite the pessimism that infects those who, like me, are of retrospective temperament and hypersensitive to deterioration. It is not hard to enumerate many things that have improved. They relate principally, but not only, to material conditions. My best friend when I was very young was one of the last children in Britain to suffer from polio, which paralyzed him from the waist down. The quickest form of written communication was then the telegram, and anything other than local telephone calls had to go through an operator. To call across the Atlantic required a reservation and was ferociously expensive; the resultant conversation always seemed to take place during a violent storm. In England, the food was generally disgusting, and meals were to be endured as a regrettable necessity instead of enjoyed (it puzzles me still how people could have cooked so badly). Cars broke down frequently, and every November, pollution produced fogs so thick that you couldn’t see the hand in front of your face (I loved them). Rationing continued for eight years after the war, and disused bomb shelters, present in every park, were where illicit sexual fumbles and smoking took place. Incidentally, for an adult male not to smoke was unusual (75 percent did so); we must have lived in a perpetual fog of foul-smelling tobacco, to judge by the distaste caused by even a single lit cigarette in these virtuous times. Poverty, as raw necessity, still existed. Murderers were sometimes hanged — as well as, more rarely, the innocent. Overt racial prejudice was, if not quite the norm, certainly prevalent.

Yet not everything has improved, though the deterioration has been less tangible than the progress. To give one example: by age 11, I was free to roam London, or at least its better areas, by myself or with a friend of the same age. The sight of an 11-year-old child wandering the city on his own did not suggest to anyone that he was neglected or abused. I remember, too, the evening papers piled up at newsstands; people would throw coins on top of the pile and take their copy. It never occurred to anyone that the money might get stolen; nowadays, it would never occur to anyone that the money would not be stolen. The crime statistics bear out this sea change in national character.

Theodore Dalrymple, “What Seventy Years Have Wrought”, New English Review, 2019-10-26.

June 25, 2024

QotD: Progress and decline

June 1, 2024

So who did write Shakespeare’s plays?

Mere mortals might be tempted to answer “Well, Shakespeare, duh!”, but to the dedicated conspiracist, the obvious is never the right answer:

This was long thought to be the only portrait of William Shakespeare that had any claim to have been painted from life, until another possible life portrait, the Cobbe portrait, was revealed in 2009. The portrait is known as the “Chandos portrait” after a previous owner, James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. It was the first portrait to be acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1856. The artist may be by a painter called John Taylor who was an important member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company.

National Portrait Gallery image via Wikimedia Commons.

Was Shakespeare a fraud? The American writer Jodi Picoult seems to think so. Her latest novel By Any Other Name is based on the premise that William Shakespeare was not the real author of his plays. Specifically, in her story, the poet Emilia Lanier (née Bassano) pays Shakespeare for the use of his name so that she might see her work staged at a time when female playwrights were extremely rare.

The theory that Shakespeare was a woman isn’t original to Picoult. As with all conspiracy theories relating to the bard, the “true” Shakespeare is identified as one of the upper echelons of society (although not an aristocrat, Lanier was part of the minor gentry thanks to her father’s appointment as court musician to Queen Elizabeth I). Those known as “anti-Stratfordians” – i.e., those who believe that the man from Stratford-upon-Avon called William Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him – invariably favour candidates who had direct connections to the court. The general feeling seems to be that a middle-class lad from a remote country town could not possibly have created such compelling depictions of lords, ladies, kings and queens.

[…]

The notion that the actor Shakespeare could have hired out his identity to Lanier, or anyone else for that matter, makes no sense if one considers the collaborative nature of the theatrical medium. Shakespeare was the house playwright for the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (the company that became the King’s Men on the accession of James I). His job was to oversee productions, to write on the hoof, to adapt existing scripts in the process of rehearsal. (This is probably why his later plays such as Henry VIII contain so many stage directions; at this point he was almost certainly residing in Stratford-upon-Avon, and so was not available to provide the necessary detail in person.) It was never simply a matter of Shakespeare dropping off his latest script at The Globe and quickly scarpering. If he was being fed the lines, it is implausible that nobody in the company would have noticed.

[…]

The theory that Shakespeare’s contemporaries – fans and critics alike – would all collude in an elaborate deception requires a full explanation. The burden of proof is very much on the anti-Stratfordians, but proof doesn’t appear to be their priority. They seem to think they know more about Shakespeare than those who actually lived and worked with him. It’s oddly hubristic.

All of this nonsense began with the Baconian theory propounded by James Wilmot in 1785 and has never gone away. The candidates are usually university educated and aristocratic: Francis Bacon, Christopher Marlowe, the Earl of Rutland, the Earl of Oxford – even Queen Elizabeth I has been proposed. The anti-Stratfordian position seems to be based on a combination of class snobbery and presentism. They assume that the middle-class son of a glover who did not attend university could not have developed the range of knowledge needed to inform his plays. They forgot, or do not know, that the grammar school education of the time would have provided a firm grounding in the classics. Shakespeare would have been steeped in Ovid, Cicero, Plautus, Terence, and much more besides. Let’s not forget that Ben Jonson, the most scholarly of all his contemporaries, didn’t go to university either.

Moreover, the plays make clear that Shakespeare was a voracious reader. The idea that one must have direct experience in order to write about a subject is very much in keeping with the obsessions of our time, particularly the notion of “lived experience” and how writers ought to “stay in their lane”.

As I’ve joked in the past, I believe the theory that Homer didn’t actually write The Iliad and The Odyssey … it was another Greek chap of the same name.

May 27, 2024

Visual metaphors in the British general election

When British PM Rishi Sunak decided to drop the writ for a general election, he must have thought he was boldly seizing the initiative but his timing was characteristically bad:

If your pitch to voters is that Britain needs protection in dangerous and uncertain times, it’s probably best to first show the voters that you can protect yourself.

For example, if it’s raining, you might want to consider demonstrating the good sense to wear a raincoat. Or carry an umbrella. Or if, say, you are the prime minister of an entire country, with an events team at your disposal, you might want to consider erecting a tent of some sort, something that can keep you dry without ruining your visuals.

Or you can be Rishi Sunak, the beleaguered British prime minister, and stand out in the pouring rain, unprotected, and get drenched as you state your case for more time to be the country’s leader, evading the storm only when re-entering the house you will surely be vacating after voters have their say on July the 4th.

To be fair to Sunak, it’s not easy to predict the weather in London. Nor can you always control the timing of events. But when it rains all of the time where you live and you do absolutely control the timing of events, as a British prime minister does when calling an election, it’s unforgivable to be unprepared. There’s a reason most Brits keep an umbrella nailed to their hips, and it’s not style.

And if you think this is to make a mountain out of a molehill, you should check out the front pages of the U.K. papers on the morning after the election call. “Drown & out”, blared The Mirror. “Drowning Street”, chortled another broadsheet. “How long will (Sunak) rain over us,” chirped in a key regional title. Each headline was accompanied by a grim looking Sunak soaked to his whippet-like core. The presentational details matter, especially when you’re putting yourself in the shop window.

Then again, to expect anything more from a Conservative movement that is running on fumes after 14 turbulent years in power is to put hope over experience. It’s been a draining (nearly) decade and a half. There was the austerity and economic uncertainty of the coalition years. The referenda — Scottish and EU — that choked off most debate on other issues in the middle part of the last decade. And then came the double act of COVID and Ukraine, a compounding whammy that hammered supply chains and put up energy and other prices, prompting the worst cost-of-living crisis in generations. It would have been enough to test any leader’s mettle, which is probably why the Conservatives have had five prime ministers during their stretch in government, including three in 2022 alone.

May 13, 2024

Archaeological Publishing – the unpalatable truth

Classical and Ancient Civilization

Published May 11, 2024Some anecdotes about publishing archaeological sites

May 7, 2024

Charles Holden and the Ministry of Truth

Jago Hazzard

Published Jan 28, 2024The strange connection between George Orwell and the London Underground.

April 24, 2024

What Were Victorian Attitudes Towards Sex?

History Hit

Published Dec 15, 2023They’re famously thought of as a buttoned up prudish bunch, but we all know they loved to bump uglies as much as anyone today.

Were the spanking punishments of boarding schools really the origins of brothels? Who were the pin-ups of Victorian women? And what did the saucy portrait Queen Victoria gave to Prince Albert look like?

Today we go Betwixt the Victorian Sheets with Dan Snow, from History Hit sister podcast Dan Snow’s History Hit, to find out all about Victorian relationships.

(more…)

April 13, 2024

QotD: Architects and modern architecture

Eventually, the deeply impoverished language of Bauhaus or Corbusian architecture became evident even to architects, possibly the most obtuse professional group in the world (though educationists are not far behind). But their turning away from the dreariness of what Professor Curl calls Corbusianity has hardly improved matters. They discovered the delights — for themselves — of originality without the discipline of even a reduced vernacular, of giving buildings outlandish shape simply because it was possible to do so, the more outlandish the more attention being drawn to themselves. Thus the skyline of the City of London has been adorned with Brobdingnagian dildoes and early mobile telephones, turning the city into a damp, overcrowded cut-price Dubai; and Paris — the City of Light — has been the dubious distinction of having built three of the worst buildings in the world, the Centre Pompidou, the Musée du Quai Branly and the Philaharmonie, the latter two by the architect who dresses like a fascist thug, Jean Nouvel. I cannot pass these buildings without thinking au bagne!; and indeed, I have a French book whose title, Faut-il pendre les architectes?, asks whether it is necessary to hang the architects.

Professor Curl’s is a very painful book to read. In one sense his targets are easy for, as the photos amply demonstrate, modernist architecture and its successors are so awful that it scarcely requires any powers of judgment to perceive it. It is like seeing a TV evangelist and knowing at once that he is a crook. Yet modernist architecture, despite its patent hideousness and inhumanity, still has its defenders, especially in the purlieus of architectural schools. Moreover, the population has been browbeaten into believing that there was never any alternative, and it is obvious that to undo the damage would take decades, untold determination and vast expenditure. Removing the Tour Montparnasse alone would probably cost several billion. No one is prepared to make this colossal effort.

What Walter Godfrey wrote in 1954 is debatable:

It is not an exaggeration to say that nine men out of ten have lost all sensitiveness to an art that was once a matter of common interest.

If this is true, it is because they have learned to accept, or swallow what they are given. The epidemiology of graffiti, however, suggests to me that, at least subliminally, men still take notice of their surrounding and are affected by them: defacement is overwhelmingly of hideous Corbusian surfaces, that is to say on what Corbusier called “my friendly concrete”.

As for the architects and their acolytes, the architectural commentators, they hide behind the claim that most people do not “understand”. They claim that modernist architecture is better than it looks or functions, that it is “honest”, a weaselly word in this context. The architects cannot recognise the obvious for the same reason that Macbeth could not stop murdering once he had started:

I am in blood

Stepped in so far that should I wade no more

Returning were as tedious as to go o’reProfessor Curl has written an essential, uncompromising, learned, sometimes slightly densely, critique of one of the worst and most significant legacies of the 20th century. He offers a slight glimmer of hope in the existence of architects who, bravely, have resisted the blandishments of celebrity status and the approbation of their corrupted peers. His book has a wonderful bibliography, the fruit of a lifetime of reading and reflection, that will give me occupation for a long time to come. It is a loud and salutary clarion call to resist further architectural fascism.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

March 13, 2024

QotD: Filthy coal

… coal smoke had dramatic implications for daily life even beyond the ways it reshaped domestic architecture, because in addition to being acrid it’s filthy. Here, once again, [Ruth] Goodman’s time running a household with these technologies pays off, because she can speak from experience:

So, standing in my coal-fired kitchen for the first time, I was feeling confident. Surely, I thought, the Victorian regime would be somewhere halfway between the Tudor and the modern. Dirt was just dirt, after all, and sweeping was just sweeping, even if the style of brushes had changed a little in the course of five hundred years. Washing-up with soap was not so very different from washing-up with liquid detergent, and adding soap and hot water to the old laundry method of bashing the living daylights out of clothes must, I imagined, make it a little easier, dissolving dirt and stains all the more quickly. How wrong could I have been.

Well, it turned out that the methods and technologies necessary for cleaning a coal-burning home were fundamentally different from those for a wood-burning one. Foremost, the volume of work — and the intensity of that work — were much, much greater.

The fundamental problem is that coal soot is greasy. Unlike wood soot, which is easily swept away, it sticks: industrial cities of the Victorian era were famously covered in the residue of coal fires, and with anything but the most efficient of chimney designs (not perfected until the early twentieth century), the same thing also happens to your interior. Imagine the sort of sticky film that settles on everything if you fry on the stove without a sufficient vent hood, then make it black and use it to heat not just your food but your entire house; I’m shuddering just thinking about it. A 1661 pamphlet lamented coal smoke’s “superinducing a sooty Crust or Furr upon all that it lights, spoyling the moveables, tarnishing the Plate, Gildings and Furniture, and corroding the very Iron-bars and hardest Stones with those piercing and acrimonious Spirits which accompany its Sulphure.” To clean up from coal smoke, you need soap.

“Coal needs soap?” you may say, suspiciously. “Did they … not use soap before?” But no, they (mostly) didn’t, a fact that (like the famous “Queen Elizabeth bathed once a month whether she needed it or not” line) has led to the medieval and early modern eras’ entirely undeserved reputation for dirtiness. They didn’t use soap, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t clean; instead, they mostly swept ash, dust, and dirt from their houses with a variety of brushes and brooms (often made of broom) and scoured their dishes with sand. Sand-scouring is very simple: you simply dampen a cloth, dip it in a little sand, and use it to scrub your dish before rinsing the dirty sand away. The process does an excellent job of removing any burnt-on residue, and has the added advantage of removed a micro-layer of your material to reveal a new sterile surface. It’s probably better than soap at cleaning the grain of wood, which is what most serving and eating dishes were made of at the time, and it’s also very effective at removing the poisonous verdigris that can build up on pots made from copper alloys like brass or bronze when they’re exposed to acids like vinegar. Perhaps more importantly, in an era where every joule of energy is labor-intensive to obtain, it works very well with cold water.

The sand can also absorb grease, though a bit of grease can actually be good for wood or iron (I wash my wooden cutting boards and my cast-iron skillet with soap and water,1 but I also regularly oil them). Still, too much grease is unsanitary and, frankly, gross, which premodern people recognized as much as we do, and particularly greasy dishes, like dirty clothes, might also be cleaned with wood ash. Depending on the kind of wood you’ve been burning, your ashes will contain up to 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH), better known as lye, which reacts with your grease to create a soap. (The word potassium actually derives from “pot ash,” the ash from under your pot.) Literally all you have to do to clean this way is dump a handful of ashes and some water into your greasy pot and swoosh it around a bit with a cloth; the conversion to soap is very inefficient (though if you warm it a little over the fire it works better), but if your household runs on wood you’ll never be short of ashes. As wood-burning vanished, though, it made more sense to buy soap produced industrially through essentially the same process (though with slightly more refined ingredients for greater efficiency) and to use it for everything.

Washing greasy dishes with soap rather than ash was a matter of what supplies were available; cleaning your house with soap rather than a brush was an unavoidable fact of coal smoke. Goodman explains that “wood ash also flies up and out into the room, but it is not sticky and tends to fall out of the air and settle quickly. It is easy to dust and sweep away. A brush or broom can deal with the dirt of a wood fire in a fairly quick and simple operation. If you try the same method with coal smuts, you will do little more than smear the stuff about.” This simple fact changed interior decoration for good: gone were the untreated wood trims and elaborate wall-hangings — “[a] tapestry that might have been expected to last generations with a simple routine of brushing could be utterly ruined in just a decade around coal fires” — and anything else that couldn’t withstand regular scrubbing with soap and water. In their place were oil-based paints and wallpaper, both of which persist in our model of “traditional” home decor, as indeed do the blue and white Chinese-inspired glazed ceramics that became popular in the 17th century and are still going strong (at least in my house). They’re beautiful, but they would never have taken off in the era of scouring with sand; it would destroy the finish.

But more important than what and how you were cleaning was the sheer volume of the cleaning. “I believe,” Goodman writes towards the end of the book, “there is vastly more domestic work involved in running a coal home in comparison to running a wood one.” The example of laundry is particularly dramatic, and her account is extensive enough that I’ll just tell you to read the book, but it goes well beyond that:

It is not merely that the smuts and dust of coal are dirty in themselves. Coal smuts weld themselves to all other forms of dirt. Flies and other insects get entrapped in it, as does fluff from clothing and hair from people and animals. to thoroughly clear a room of cobwebs, fluff, dust, hair and mud in a simply furnished wood-burning home is the work of half an hour; to do so in a coal-burning home — and achieve a similar standard of cleanliness — takes twice as long, even when armed with soap, flannels and mops.

And here, really, is why Ruth Goodman is the only person who could have written this book: she may be the only person who has done any substantial amount of domestic labor under both systems who could write. Like, at all. Not that there weren’t intelligent and educated women (and it was women doing all this) in early modern London, but female literacy was typically confined to classes where the women weren’t doing their own housework, and by the time writing about keeping house was commonplace, the labor-intensive regime of coal and soap was so thoroughly established that no one had a basis for comparison.

Jane Psmith, “REVIEW: The Domestic Revolution by Ruth Goodman”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-05-22.

1. Yeah, I know they tell you not to do this because it will destroy the seasoning. They’re wrong. Don’t use oven cleaner; anything you’d use to wash your hands in a pinch isn’t going to hurt long-chain polymers chemically bonded to cast iron.

February 21, 2024

QotD: Mid-century London

Two of the novels were by, respectively, Nigel Balchin and R. C. Hutchinson, writers well regarded in their time but now mostly forgotten, while the third was by Ivy Compton-Burnett, who still has her admirers. They were quite different authors, but each had an unmistakable quality of unreconstructed English national identity, such as no writer about London — where two of the novels are set — or anywhere else in the country could now convey.

It is not that foreigners could not be found in 1949 London, which was then still a port city of some importance. In Hutchinson’s book, Elephant and Castle, set largely in the East End, one of the main characters is half-Italian, and foreigners of various nationalities have walk-on parts. But they in no way affect the strongly English character of the city. Today’s London, by contrast, seems more like a dormitory for an ever-fluctuating population than a home; even much of its physical fabric has been completely denationalized by modernist architecture of a sub-Dubai quality. It is not a melting pot, for little is left to melt into; a better culinary metaphor might be a stir-fry, the ingredients remaining unblended — though, with luck, compatible.

Theodore Dalrymple, “What Seventy Years Have Wrought”, New English Review, 2019-10-26.

December 11, 2023

QotD: The Palace of Westminster

Work outwards from this change and you will begin to have some idea of how much Britain has altered. The bits you don’t or can’t see are as unsettlingly different as those tattoos. Look up instead at the Houses of Parliament, all pinnacles, leaded windows, Gothic courtyards and cloisters, which look to the uninitiated as if they are a medieval survival. In fact they were completed in 1860, and are newer than the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The only genuinely ancient part — not used for any governing purpose — is the astonishing chilly space of Westminster Hall, faintly redolent of the horrible show trial of King Charles I, still an awkward moment in the national family album. But those who chose the faintly unhinged design wanted to make a point about the sort of country Britain then was, and they were very successful. Gothic meant monarchy, Christianity, and conservatism. Classical meant republican, pagan, and revolutionary, and mid-Victorian Britain was thoroughly wary of such things, so Gothic was chosen and the Roman Catholic genius Augustus Welby Pugin let loose upon the design. Wherever you are in the building, it is hard to escape the feeling of being either in a church, or in a country house just next to a church. The very chimes of the bell tower were based upon part of Handel’s great air from The Messiah: “I know that my Redeemer liveth”.

I worked for some years in this odd place. It is by law a Royal Palace, so nobody was ever officially allowed to die on the premises, in case the death had to be inquired into by some fearsome, forgotten tribunal, perhaps a branch of Star Chamber. Those who appeared to have deceased were deemed to be still alive and hurried to a nearby hospital where life could be pronounced extinct and an ordinary inquest held. We were also exempt from the alcohol laws that used in those days to keep most bars shut for a lot of the time, and if the drinks were not free they were certainly amazingly cheap.

In my years of wandering its corridors and lobbies, of hanging about for late-night votes and dozing in committee rooms, I came to loathe British politics and to mistrust the special regiment of journalists (far too close to their sources) who write about it. I had hoped for a kingdom of the mind and found a squalid pantry in which greasy, unprincipled deals were made by people who were no better than they ought to be.

But I came to love the building. Once you had got past the police sentinels, who knew who everyone was, you could go everywhere, even the thrilling ministerial corridor behind the Speaker’s chair, from which Prime Ministers emerged to face what was then the genuine ordeal of Parliamentary questions, twice a week. There was a rifle range beneath the House of Lords, set up during World War I to make sure honorable members of both Houses would be able to shoot Germans accurately if they ever met any. There was a room where they did nothing but prepare vast quantities of cut flowers, and which perfumed the flagstone corridor in which it lay. There was a convivial staff bar (known to few) where the beer was the best in the building and politicians in trouble would hide from their colleagues. The Lords had a whole half of the Palace, with lovely murals illustrating noble moments of our history, and the Chief Whip’s cosy, panelled office where reporters would be summoned once a week for dangerous gossip and perilously large glasses of whisky or very dry sherry, generously refilled. And high up in the roof, looking down over the murky Thames, was the room where the government briefed us, in meetings whose existence we were sworn never to reveal. Now they are pretty much public, so the real briefings must happen somewhere else, I suppose.

Peter Hitchens, “An Empty Parliament”, First Things, 2017-10-03.

November 25, 2023

Crystal Palace Station is Needlessly Magnificent

Jago Hazzard

Published 9 Aug 2023Crystal Palace and the station built for it. Well, one of them.

(more…)

November 5, 2023

Guy Fawkes and The Gunpowder Plot 1605

The History Chap

Published 4 Nov 2022The story behind Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, the audacious plan to kill the king of England. It is also the complicated story behind our annual Bonfire Night celebrations.

In 1605 a group of dissident Catholics came within a whisker of one of the greatest assassination coups in history — blowing up the King of England, and his government as he attended parliament in London. 36 barrels of gunpowder (approximately 1 tonne of explosives) had been placed directly under where he would open parliament. Experts estimate that no one within 300 feet would have survived.

Had it succeeded it would have rivalled 9/11 in its audacity and would have changed English (& arguably world) history forever. But who were the plotters, what were they trying to achieve and how close did they really come to success? Were they freedom fighters or 17th century terrorists? And why is only one conspirator, Guy Fawkes, remembered when he wasn’t even the brains behind the operation?

After years of persecution by England’s Protestants, a small group of Catholic nobles under Robert Catesby (aka Robin Catesby) decided to take matters into their own hands and blow up the king (King James I of England / James VI of Scotland) whilst he attended parliament in London.

Guy Fawkes (aka Guido Fawkes) smuggled 36 barrels of gunpowder into a cellar directly beneath the hall where parliament would meet in the Palace of Westminster. In the early hours of 5th November 1605, he was arrested by guards who had been tipped off about the gunpowder plot. After three days of torture in the Tower of London, Guy Fawkes finally broke and named his fellow conspirators.

The conspirators, under Robert Catesby, had fled London for the English midlands where they hoped to abduct the king’s daughter and organise a catholic rising. Both failed to materialise and Catesby’s small band were surrounded by a government militia at Holbeach House, just outside Kingswinford in Staffordshire. A brief shoot-out resulted in the death of some of the Catholic rebels (including their leader, Catesby) and the arrest of the others.

The surviving gunpowder plotters (including Guy Fawkes) were executed in London at the end of January 1606, by the grisly execution reserved for traitors — Hanged, drawn and quartered (quite literally a “living death”).

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a complete failure but the event is still celebrated on the 5th November every year on Bonfire Night.

(more…)

October 25, 2023

Housing for Hamas leadership … in London

In the non-paywalled part of a post from Ed West, we have a look at the terrible conditions leaders for Hamas and other terrorist organizations have to put up with in the embattled suburbs of … London:

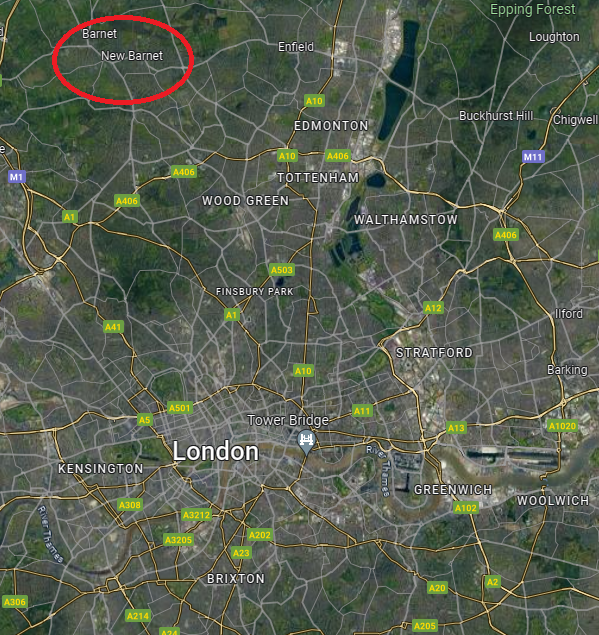

Barnet, to those unfamiliar with this corner of the world, is the most Jewish borough in Britain, an area of north-west London often described as “leafy” and including both pleasant inner suburbs like Finchley as well as areas of genuine countryside. The migration of eastern European Jews in the capital followed an anticlockwise direction from impoverished Whitechapel in east London up through Hackney and Haringey in the north, with Barnet the next stop.

It is also, strangely, home to a leading fundraiser for Hamas, the terrorist group responsible for the murder of 1,400 people in southern Israel earlier this month and quite explicitly committed to the eradication of Jews in the Holy Land.

What with London house prices being what they are, you wonder how he managed it, but of course Muhammad Qassem Sawalha, who “ran the group’s terrorist operations in the West Bank”, according to the Sunday Times, managed to buy his property with help from the council.

Despite being a known and wanted terrorist, Sawalha was allowed to settle in Britain in the 1990s and obtain British citizenship. He continued to work for Hamas, holding talks about committing terrorist acts and laundering money for the group, according to the US Department of Justice. In 2009 he signed the Istanbul Declaration which praised God for having “routed the Zionist Jews”, and called for a “Third Jihadist Front” to be “opened in Palestine alongside Iraq and Afghanistan”, according to the paper.

All the while he was benefitting from Britain’s social housing system. In 2003, Barnet Council made him a council tenant and he was housed in a two-storey property with a garden and garage in the borough, where he still lives.

Two years ago, Sawalha and his wife used the Right to Buy scheme to acquire their home for £320,700, with Barnet Council giving them a £112,300 discount on its market value.

This is despite the fact that in 2006 Panorama reported that Sawalha was “said to have masterminded much of Hamas’ political and military strategy” and that, “although he was known to MI5, the ‘authorities let him operate freely here'”. Not just let him operate freely, but sort him out with a house – and if you think this sounds insane, it is not at all uncommon.

Sawalha’s old comrade, the famous hook-handed hate preacher Abu Hamza, was also given a huge house courtesy of the British taxpayer. The Egyptian was allowed to live rent-free in a five-bedroom house in what the Mail described as “upmarket Shepherd’s Bush”, a phrase I would have found astonishing to read as a teenager in west London.

Shepherd’s Bush is next door to super-rich Holland Park, and private property is extremely expensive there – but it also has high levels of social housing, as with much of central London, so “upmarket” might be stretching it.

September 19, 2023

For some reason, ordinary Londoners don’t seem to appreciate Mayor Khan’s ULEZ initiatives

It’s hard to believe that anyone could possibly want to avoid London Mayor Sadiq Khan’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) expansion beyond the initial areas of the city, but a quick search of Twit-, er, I mean “X” shows evidence of what Justin Trudeau might characterize as a “small fringe minority … holding unacceptable views”:

Weird, isn’t it. All those “decommissioned” cameras. And people physically blocking access to workers:

London has put up with a lot over the centuries, but Mayor Khan’s ULEZ somehow seems to have awakened the resistance in a major way:

Brian Peckford republished this article from Yudi Sherman on the pushback against London’s ULEZ expansion:

London taxpayers are damaging the city’s surveillance vans in an escalating feud between Mayor Sadiq Khan and the city’s residents.

Last month Khan peppered the city with ultra-low emission zones (ULEZs), areas in London accessible only to low-emission vehicles. Cars that do not meet the city’s environmental standards are charged £12.50 ($16) for entering the ULEZ. Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras positioned around the zones read license plates and check them against the vehicles’ make and model in real time. If a vehicle does not meet the environmental threshold, the fine is levied against the car owner. Failure to pay can lead to fines as high as £258 ($331).

The ULEZ climate mandate has drawn heavy protests from residents, including hunger strikes and refusal to pay fines. Taxpayers have also taken to disabling the ANPR surveillance cameras which Transport for London (TfL), the city’s transportation department, said will be used both for climate and law enforcement.

In response, the city deployed mobile surveillance vans mounted with ANPR cameras across London in the hopes of evading attacks, but the vans are being targeted as well. Some have been spotted covered in graffiti with their tires slashed, while others have been completely covered in tarp, reports the Daily Mail.

The activists are said to belong to a group calling itself the Blade Runners and have promised not to rest until every ULEZ camera is removed or destroyed “no matter what”. The group is being widely cheered by its compatriots, including media personality and political commentator Katie Hopkins. Over 4,000 people have joined a Facebook group to report ULEZ van sightings.

Between April 1st and August 31st, police recorded 351 incidents of destruction to ULEZ cameras and 159 removals, reports Sky News, an average of over 100 a month. Of those incidents, 171 reportedly occurred since August 17th alone, just before the ULEZ mandate officially expanded to include all outer London boroughs. Two individuals have been arrested in connection with the incidents, one of whom was charged.

One reported Blade Runner said, “In terms of damage it’s way more than what [London Mayor Saidq Khan and TfL] have stated.”

September 1, 2023

Grassroots protests continue against London’s expanded ULEZ

London mayor Sadiq Khan’s “Ultra Low Emission Zone” expansion is not sitting well with the people who see it as an undemocratic imposition on the poorest Londoners:

This week many Londoners are waking up to the impact of living in an Ultra Low Emission Zone as the £12.50 daily charge for unfashionable cars begins in the outer poorer suburbs.

Normally “climate change” costs are secretly buried in bills, hidden in rising costs and blamed on “old unreliable coal plants”, inflation or foreign wars. Your electricity bill does not have a category for “subsidies for your neighbors’ solar panels”. But the immense pain of NetZero can’t be disguised.

For a pensioner on £186 a week it could be as much as an £87 a week penalty for driving their car — or £4,500 a year. The Daily Mail is full of stories of livid and dismayed people who served in the Navy or worked fifty years, who can’t afford to look after older frail Aunts or shop in their usual stores now, or who will have to give up their cars. People are talking about the “end of Democracy”. The cameras are expected to bring in £2.5 million a day in ULEZ charges to City Hall. But shops inside the zone may also lose customers, and everyone, with and without cars will have to pay more for tradespeople and deliveries to cover the cost of their new car or Ulez fee.

Protests have reached a new level of anger and hooded vigilantes in masks carry long gardening clippers, or spray cans and lasers to disable cameras that record number plates for Ulez. In one photo the whole metal camera pole has been sheared by an electric saw of some sort. There chaos.

Interactive maps have sprung up to report where the cameras are, and help people “plan their trips”. The vigilante group called Blade Runners have vowed to remove or disable every ULEZ camera in London. Nearly nine out of ten cameras have been vandalized in South-east London.

The Transport for London website was overwhelmed with searches from people wondering if their car was compliant and they would have to pay just to drive on the roads their taxes and fees built. Some people have bought old historic cars to get around the fee, but apparently a lot of people hadn’t thought much about what was coming. Sadiq Khan probably didn’t mention this in his election campaign. Presumably there are others in London who will get a nasty surprise bill in the mail.

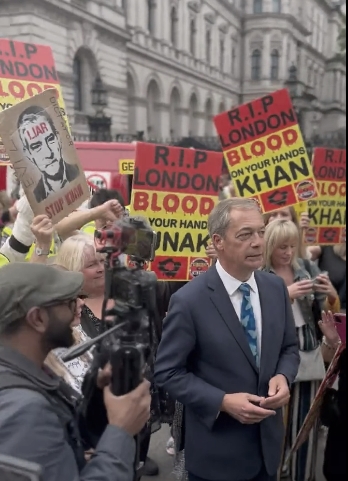

As Nigel Farage says: “I’ve never seen people so angry about this new tax on working people. “And people are not just furious at Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London, they’re angry at the Prime Minister and the Conservatives for not stopping the scheme.