Army University Press

Published 22 Nov 2024The Battle of Huế is known for urban combat, destruction, and anguish. The city of Huế mattered to all the combatant forces. The city and its people paid the price. Interviews with noted subject matter experts Drs. Pierre Asselin, Gregory Daddis, James Willbanks, and Cpt. Wyatt Harper are augmented with archival audio and film, and detailed maps. This documentary places the Battle of Huế within the context of Hanoi’s 1968 Tet Offensive. How North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the United States perceived the Vietnam War in 1967 and 1968 are central to this documentary. Covered are the key moments of the battle — including the People’s Armed Forces of Vietnam (PAVN) and People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) planning and assault on Hue. The responses of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), Vietnam Marine Corps (VNMC), the United States Marine Corps (USMC), and the U.S. Army (USA) are addressed to offer insight into an informative example of urban warfare.

0:02:39 – Why the Tet Offensive

0:10:53 – Why Huế

0:15:53 – Military Decision Making Process | Doctrine

0:26:51 – Warfighting Function | Doctrine

0:27:59 – Paralysis by analysis | Doctrine

0:33:15 – Courses of action | Doctrine

0:38:22 – Weather and operations | Doctrine

0:40:52 – Huế Massacre

0:41:18 – My Lai

0:46:05 – Huế and Modern Warfare

April 14, 2025

Huế: Battle for the Heart of Vietnam

January 24, 2025

The end of “affirmative action” in US government hiring

In The Free Press, Coleman Hughes outlines how the US federal government got into the formal habit of hiring and promoting staff based on things other than ability and merit during the Nixon administration:

Trump’s Executive Order 14171 is titled Ending Illegal Discrimination and Restoring Merit-Based Opportunity. It describes how vast swaths of society, including the “Federal Government, major corporations, financial institutions, the medical industry, large commercial airlines, law enforcement agencies, and institutions of higher education have adopted and actively use dangerous, demeaning, and immoral race- and sex-based preferences under the guise of so-called ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ (DEI)”.

In response, Trump has ordered the executive branch and its agencies “to terminate all discriminatory and illegal preferences, mandates, policies, programs, activities, guidance, regulations, enforcement actions, consent orders, and requirements”.

That is a lot of preferences and mandates. Trump’s executive order accurately describes the enormousness of the DEI bureaucracy that has arisen in government and private industry to infuse race in hiring, promotion, and training. Take, for example, the virtue-signaling announcements made by big corporations in recent years — such as CBS’s promise that the writers of its television shows would meet a quota of being 40 percent non-white.

And so, we will now see what federal enforcement of a color-blind society looks like. We’ll certainly see how many federal employees were assigned to monitor and enforce DEI — Trump has just demanded they all be laid off.

The most controversial part of this executive order is that it repeals the storied, 60-year-old Executive Order 11246, signed by President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Johnson’s original order mandated that government contractors take “affirmative action” to ensure that employees are hired “without regard to their race, color, religion, or national origin”.

The phrase affirmative action, however, has come to have a profoundly different meaning for us than it did during the 1960s civil rights era. Back then, it simply meant that companies had to make an active effort to stop discriminating against blacks, since antiblack discrimination was, in many places, the norm. Only later did the phrase come to be associated with the requirement to actively discriminate in favor of blacks and other minorities.

One of the great ironies of affirmative action is that it was not a Democrat but a Republican president, Richard Nixon, who did more than anyone to enshrine reverse racism at the federal level by establishing racial quotas. According to the Richard Nixon Foundation, “The Nixon administration ended discrimination in companies and labor unions that received federal contracts, and set guidelines and goals for affirmative action hiring for African Americans”. It was called the “Philadelphia Plan” — the city of its origin.

For the first time in American history, private companies had to meet strict numerical targets in order to do business with the federal government. Philadelphia iron trades had to be at least 22 percent non-white by 1973; plumbing trades had to be at least 20 percent non-white by the same year; electrical trades had to be 19 percent non-white, and so forth.

In the intervening decades, this racial spoils system has not only caused grief for countless members of the unfavored races — it has also created incentives for business owners to commit racial fraud, or else to legally restructure so as to be technically “minority-owned”. As far back as 1992, The New York Times reported that such fraud was “a problem everywhere” — for instance, with companies falsely claiming to be 51 percent minority-owned in order to secure government contracts. In a more recent case, a Seattle man sued both the state and federal government, claiming to run a minority-owned business on account of being 4 percent African.

November 30, 2024

October 24, 2024

Did the Media Lose the Vietnam War?

Real Time History

Published Jun 21, 2024In late April 1975, dramatic images from Saigon are beamed across the world. North Vietnamese troops proclaimed final victory. Just how did the US lose the Vietnam War?

(more…)

September 10, 2024

Why the US Left Vietnam

Real Time History

Published Apr 19, 2024With violent anti-war protests at home and discipline problems on US bases, President Nixon promises to withdraw American troops from the Vietnam War, but that doesn’t mean an end to the fighting. As US troop numbers drop, the war expands across borders and in the air as more weapons are pumped into the South.

(more…)

June 19, 2024

Why the US Lost the Tet Offensive Despite Beating the NVA

Real Time History

Published Feb 16, 2024After years of boots on the ground and bloody combat in Vietnam, US officials are publicly confident. The strategy of eliminating the Viet Cong is working. The North Vietnamese communist forces are on their last legs and victory is only a matter of time. Or so they say. But as 1968 and the traditional lunar new year festivities begin, US and South Vietnamese troops find themselves on the receiving end of a formidable North Vietnamese surprise attack: The Tet Offensive.

(more…)

October 23, 2023

QotD: The real meaning of “Watergate”

I was reflecting this week on my brief stint, many years ago, as a newspaperman. It was a job I loved. I signed on not too many years after the Watergate scandal, and journalists were still flush with heroic ideas about themselves. Woodward and Bernstein — and all reporters by extension — had toppled a corrupt presidency and saved the republic and the Constitution from the kind of behind-the-scenes government tyranny dramatized in such thriller films as The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor.

[…]

Recently, reading Mark Levin’s Unfreedom of the Press, I was reminded that, before reporters went on their great crusade against Richard Nixon, they had overlooked a whole lot of corruption in the Democrat presidents who preceded him.

Levin tells how John F. Kennedy, with the knowledge of his brother and Attorney General Robert, nudged the IRS into auditing conservative groups. With Kennedy’s approval, the FBI was also employed to investigate those the administration disliked, including Martin Luther King Jr. Lyndon Baines Johnson would later increase the politically motivated auditing and spying. None of this was uncovered until later on.

Ben Bradlee — the editor of the Washington Post, where Woodward and Bernstein broke the Watergate story — was well aware of his pal Kennedy’s misuse of the tax and investigative agencies. Not only did he not report it, he allowed himself and his paper to be manipulated by information JFK had wrongly obtained.

This totally changes the Watergate narrative. Nixon’s dirty tricks and enemy lists may have been creepy and wrong, but the press exposure of these misdemeanors came after years of ignoring similar and worse malfeasance by Democrat administrations.

That changes what Watergate means. That transforms it from a heroic crusade into a political hit job, Democrat hackery masquerading as nobility. The press turned a blind eye to the corruption of JFK and LBJ, then raced to overturn the election of a man they despised — despised in part because he battled the Communism many of them had espoused.

Andrew Klavan, “‘Watergate’ Doesn’t Mean What the Press Thinks It Means: The press turned a blind eye to the corruption of JFK and LBJ, then raced to overturn the election of a man they despised”, The Daily Wire, 2019-08-31.

October 14, 2023

Why Did the Vietnam War Break Out?

Real Time History

Published 10 Oct 2023In 1965, US troops officially landed in Vietnam, but American involvement in the ongoing conflict between the Communist North and the anti-Communist South had started more than a decade earlier. So, why did the US-Vietnam War break out in the first place?

(more…)

May 10, 2021

They don’t make politicians like Lyndon Johnson anymore … thank goodness

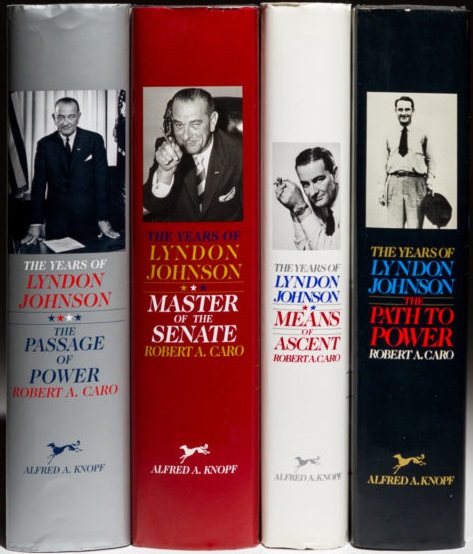

Another of the reader-contributed book reviews at Astral Codex Ten considers the personal history and astounding political career of LBJ, as told by biographer Robert Caro:

2: LBJ’s guide to amassing power

(i) Seduce older men

(Eww, not like that.) LBJ had a gift for becoming a “professional son” to any powerful man. At college, LBJ sat at professors’ feet and stared at them as if they were God’s gift to the educational system. LBJ constantly ran errands for the college president, Prexy Evans, and wrote glowing editorials about him.

LBJ’s fellow students were not amused. One said:

“Words won’t come to describe how Lyndon acted toward the faculty — how kowtowing he was, how suck-assing he was, how brown-nosing he was.”

But this flattery paid off. Evans put LBJ in charge of the financial aid program. Yes, really. And when other students wrote nasty comments about LBJ in the yearbook (e.g. the time he stole the Student Council elections), Evans ordered professors to cut out those pages with razors.

LBJ would repeat this flattery with President (Franklin) Roosevelt, Speaker Rayburn, and Senator Russell.

(ii) Treat your employees like dirt

LBJ wanted his staff to be absolutely loyal, so he could direct them like chess pieces. He found their weak points — their weight, their divorce — and mercilessly taunted them. I’m not going to describe the crude things he did.

Before his marriage, LBJ treated Lady Bird like an angel; once they were married, he treated her like one of his employees.

[…]

(v) Use money in new and exciting ways

LBJ funneled government contracts to Brown & Root, a construction company. In return, they gave his campaign gobs of money. During the 1948 election, two of his campaign staff ate at a cafe and then accidentally left behind a brown paper bag containing $50,000 in cash (more than $500,000 in today’s money). Luckily no one stole it.

Using all of this money, LBJ was able to make the media say whatever he wanted about his opponent, Coke Stevenson. He hired “missionaries” to hang out in bars and spread rumors about Stevenson. Thousands of federal workers also repeated LBJ’s talking points.

(vi) Cheat

But Stevenson was a storybook character, so money couldn’t defeat him. He simply told the people of Texas that he would continue to do the right thing, and they believed him. LBJ had lost the 1941 Senate election because Pappy O’Daniel had cheated better than he did. Now LBJ would cheat, and he would cheat big.

In 1940s Texas, basically every type of election fraud was real: Dead people voting, county bosses writing down whatever numbers they wanted, Mexicans being hired to cross the border and vote, etc. By buying tens of thousands of votes, LBJ was almost able to close the gap between him and Coke Stevenson. That wasn’t enough, so six days after the election, Luis Salas “found” 200 more votes for LBJ, giving him a margin of victory of 0.01%.

September 29, 2020

April 12, 2020

QotD: The Gini coefficient

At least for now, most progressives acknowledge that markets and economic growth are necessary. But progressives in academia contend that growth has proved itself secondary to equality efforts — something to be exploited, rather than appreciated. Not just nationally, but worldwide, policymakers and the press regard the subordination of growth to equality to be a benign practice, as in the recent line in the Indian periodical Mint: a policy aimed at “reducing inequality need not hurt growth.”

The redistributionist impulse has brought to the fore metrics such as the Gini coefficient, named after the ur-redistributor, Corrado Gini, an Italian social scientist who developed an early statistical measure of income distribution a century ago. A society where a single plutocrat earns all the income ranks a pure “1” on the Gini scale; one in which all earnings are perfectly equally distributed, the old Scandinavian ideal, scores a “0” by the Gini test. The Gini Index has been renamed or updated numerous times, but the principle remains the same. Income distribution and redistribution seem so crucial to progressives that French economist Thomas Piketty built an international bestseller around it, the wildly lauded Capital.

Through Gini’s lens, we now rank past eras. Decades in which policy endeavored or managed to even out and equalize earnings — the 1930s under Franklin Roosevelt, the 1960s under Lyndon Johnson — score high. Decades where policymakers focused on growth before equality, such as the 1920s, fare poorly. Decades about which social-justice advocates aren’t sure what to say — the 1970s, say — simply drop from the discussion. In the same hierarchy, federal debt moves down as a concern because austerity to reduce debt could hinder redistribution. Lately, advocates of economically progressive history have made taking any position other than theirs a dangerous practice. Academic culture longs to topple the idols of markets, just as it longs to topple statutes of Robert E. Lee.

But progressives have their metrics wrong and their story backward. The geeky Gini metric fails to capture the American economic dynamic: in our country, innovative bursts lead to great wealth, which then moves to the rest of the population. Equality campaigns don’t lead automatically to prosperity; instead, prosperity leads to a higher standard of living and, eventually, in democracies, to greater equality. The late Simon Kuznets, who posited that societies that grow economically eventually become more equal, was right: growth cannot be assumed. Prioritizing equality over markets and growth hurts markets and growth and, most important, the low earners for whom social-justice advocates claim to fight. Government debt matters as well. Those who ring the equality theme so loudly deprive their own constituents, whose goals are usually much more concrete: educational opportunity, homes, better electronics, and, most of all, jobs. Translated into policy, the equality impulse takes our future hostage.

Amity Shlaes, “Growth, Not Equality”, City Journal, 2018-01-21.

March 9, 2020

QotD: The wrong lessons learned from World War II

Americans learned several misleading lessons from World War II. The first and greatest error was overestimating the effectiveness of military force. World War II — the last conflict in which the world’s great powers went toe-to-toe against each other, with no holds barred — created a new understanding of how wars are fought and won. But wars since then have not fit this paradigm, and many of our subsequent military mistakes came as a result of misapplying World War II’s lessons.

Lyndon Johnson led the country into a massive military commitment in South Vietnam in part because of misplaced faith in what the United States could accomplish by force of arms. The Johnson administration convinced itself that fighting modern wars was a branch of management science, akin to running a large corporation like General Motors, and that America’s military was a versatile instrument that could be dialed up or down to deliver precisely calibrated levels of violence, tailored to meet any foreign policy challenge. World War II also led many Americans to conclude that liberal democracy could be imposed on foreign peoples through the application of what George W. Bush’s administration would later call “shock and awe.”

It turns out that, even in the age of precision weapons, military power is a blunt instrument, ill-suited to nation-building, except in rare circumstances and at great cost. Germany and Japan — our preferred examples — are highly idiosyncratic. Liberal democracy flourished in each only after the deaths of millions of citizens and the reduction of their societies to rubble. Americans haven’t shown much stomach for projects of this scope after 1945.

E. M. Oblomov, “The Greatest Generation and the Greatest Illusion: Success in World War II led Americans to put too much faith in government—and we still do.”, City Journal, 2017-12-28.

January 21, 2020

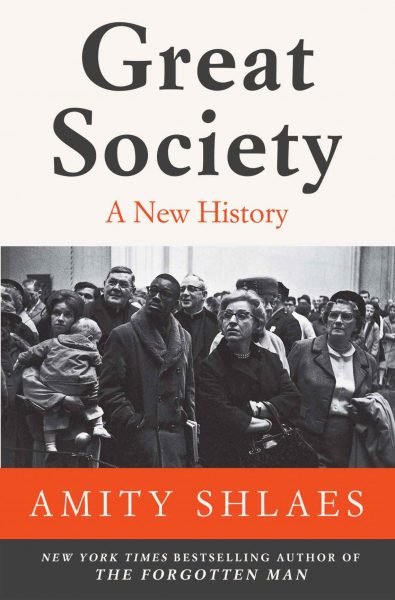

Amity Shlaes’ Great Society: A New History

In City Journal, Edward Short reviews the latest American economic history book by Amity Shlaes:

In Great Society: A New History, Amity Shlaes revisits the welfare programs of the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations to show not only how misguided they were but also what a warning they present to those who wish to resurrect and extend such programs. “The contest between capitalism and socialism is on again,” the author writes in her introduction. Despite the Trump administration’s thriving economy, or perhaps because of it, Democratic Party progressives are calling for new welfare programs even more radical than those advocated in the 1960s by the socialist architect of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, Michael Harrington. In the new schemes for wealth redistribution, student debt relief, socialized medicine, and universal guaranteed income that make up the Democrats’ political platform in 2020, Shlaes rightly sees a recycling of Great Society hobby horses — and she worries that a good portion of the electorate may be taken in by them. “Once again many Americans rate socialism as the generous philosophy,” she observes, and she has written her admirable, sobering study to make sure that readers realize that the “results of our socialism were not generous.”

Reviewing how ungenerous makes for salutary reading. After all, socialism of any stripe, whether in Russia, South America, Europe, or America, has always been an inherently deceitful enterprise. Shales captures the essence of this imposture when she describes one of its manifestations as “Prettifying a political grab by dressing it up as an economic rescue.” In totting up these receipts for deceit, Shlaes has done a genuine public service. […]

On display here are all of Shlaes’s strengths as an author: her clear and unpretentious prose, sound critical judgment, readiness to enter into the thinking of her subjects with sympathy (even when she regards it as mistaken), and, perhaps most impressively, understanding how history can help us fathom what might otherwise be obscure in our own more immediate history.

Accordingly, she describes the influence that Roosevelt’s New Deal had on Johnson, who saw it as a model for maintaining and consolidating his Democratic majorities, as well as focusing his Cabinet’s talents. “The men around Johnson,” Shlaes points out, including Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, Richard Goodwin, and Sargent Shriver, “felt the weight of his faith on them, and strove hard. Vietnam would be sorted out. There would be a Great Society. Poverty would be cured. Blacks of the South would win full citizenship. The Great Society would succeed.” Yet the president’s men could not help asking “by what measures” it would succeed.

Moynihan’s answer to this question is one that still mesmerizes social-engineering elites. The Great Society would be achieved by social science. “Progress begins on social problems when it becomes possible to measure them,” Moynihan declared. Improved quantitative analysis would give the centralized power of planners a new credibility.

Whether Johnson himself ever truly believed in such claims is questionable. When aides asked the exuberant Texan what he thought of the risks of going forward with his wildly ambitious program, his reply epitomized the hubris at the heart of his Great Society: “Well, what the hell’s the presidency for?”

January 12, 2020

December 7, 2019

History of Space Travel – One Small Step – Extra History – #5

Extra Credits

Published 5 Dec 2019Start your Warframe journey now and prepare to face your personal nemesis, the Kuva Lich — an enemy that only grows stronger with every defeat. Take down this deadly foe, then get ready to take flight in Empyrean! Coming soon! http://bit.ly/EHWarframe

The United States was losing the space race. A number of unfortunate missteps and mistakes had hindered their progress. But the United States had also structured its space program entirely differently from the USSR. Instead of being helmed by the military, the National Aeronautics & Space Administration was created by Eisenhower with an emphasis on exploration and research. And in the end, the later but more advanced satellites will collect the data required a dream firmly placed in the American consciousness by JFK. A dream to place a man on the moon.

From the comments:

Extra Credits

19 hours ago

The plaque still gives me goosebumps in the best way possible. Hopefully one day we can live up to its promise of peace. Be good to one another. ❤️And thanks to Rebecca Ford (the voice of Lotus) for voicing space mom at the end of each of these episodes. They’ve been a blast to make and we hope that you all have enjoyed this trip to the stars.