OTD Military History

Published 7 Aug 2023The Battle of Amiens started on August 8 1918. It started the process that caused the final defeat of the German Army on the battlefield during World War 1. Many people falsely claimed that the German Army was not defeated on the battlefield but at home by groups that wished to see German fall. One person who helped to create this myth was German General Erich Ludendorff. He called August 8 “the black day of the German Army”.

See how this statement connects to the stab in the back myth connects to Amiens and the National Socialists in Germany.

(more…)

August 8, 2023

How the Battle of Amiens Influenced the “Stab in the Back” Myth

July 24, 2023

QotD: The Duke and Duchess of Windsor after the abdication

The author laces his chapters with some memorable phraseology. Of the wedding of David and Wallis in France on 3 June 1937, we are reminded, “Only the most cynical could have begrudged the pair their happy ending, although it remained ambiguous as to who was the dashing prince and who the swooning maiden.” With another coronation in the offing this year, [The Windsors at War author Alexander] Larman dwells on that of George VI (known hitherto at Bertie) at Westminster Abbey on 12 May 1937. All the time, we are reminded that the new king loathed the debonair confidence of “the king across the water”, fearing that if he made a hash of the kingship he never wanted, his scheming elder brother might return. This is one theme that runs throughout Larman’s fine scholarship.

We are reminded that the king’s much-rehearsed coronation speech was a success. “Millions of his subjects sat at home listening to the broadcast, willing him to succeed whilst knowing of his stammer and the difficulties that even speaking a few short sentences publicly had caused him … Yet fortunately for the coronation ceremony, the king’s nerves seemed to vanish on the day, aided by his sincere religious faith: another characteristic absent from his brother’s life.”

[…]

One trait that runs through this important book is the personal weakness of the Duke and the compelling strength of his bride. Larman makes it plain that both Baldwin and Chamberlain were aware that it was Wallis who was passing state secrets to German intelligence, although her husband also expressed sympathies for Hitler’s regime. Cecil Beaton, photographer of the David-Wallis wedding in France, noted in his diary that the Duchess “not only has individuality and personality, but [she] is a strong force”. Even as he praised her intelligence and admiration for the Duke, Beaton offered the judgement that she “is determined to love him, though I feel she is not in love with him” — an interesting reflection on the woman for whom her husband had abandoned his throne. In 2015, Andrew Morton dwelt in great detail on Wallis’s treachery in 17 Carnations: The Windsors, The Nazis and The Cover-Up.

Throughout Larman’s compelling read, we are offered evidence of how tone-deaf the Duke was to international protocol, the interests of Britain and the sufferings of others. Anthony Eden, as Foreign Secretary, observed how the pair felt they should be “treated abroad by ambassadors and dignitaries, rather as they would a member of the royal family on a holiday”. This came to a head when friends of the Duke organised a visit to Germany over 11–23 October 1937. They met several leading Nazis, including Hess, Goebbels (who called the Duke “a tender seedling of reason”) and Göring, as well as renewing their acquaintance with Ribbentrop, still then ambassador to Britain. It was Ribbentrop, according to Morton’s book, who had sent Wallis 17 carnations daily “each one representing a night they had spent together”.

On the penultimate day, the Windsors met Hitler at Berchtesgaden. Larman reasons that the visit was as much to show that the Duke and his bride were still relevant in the wider world, as to form a bond with the Führer to avoid future war. As with many public figures of the era, David feared communism far more than fascism, for which he saw the best antidote in an alliance with Germany. We are left wondering whether the Duke observed in Hitler’s authoritarian state all that he admired and wished for Britain, but was now denied.

A subtext to The Windsors at War is just how much anxiety David caused the King, his younger brother, during the run up to war and during it. For most of the period, the Duke badgered for money, confirmation of his status and a royal title for Wallis. Whilst the first was forthcoming, amounting to a financial settlement of £25,000 a year (generous by any standards, considering the Windsors spent their days sofa-surfing and sponging off their rich friends), neither of the latter were. Chamberlain was forced to write that “in addition to letters of protest he had as Prime Minister … all classes stood against him. In addition to the British not wanting him to return, residents of Canada, New Zealand and America wished him to remain in exile”.

Yet, writes Larman, the Duke would not simply “languish in exile and be denied the opportunity to contribute his thoughts on the international situation. This arrogance made him both unpredictable and, with the outbreak of war drawing closer, dangerous. At a time when it was crucial that the loyalties of prominent public figures were transparent, his inclinations remained opaque”.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “The other one”, The Critic, 2023-04-18.

July 22, 2023

Did Japan Start WW2 in 1937?

Real Time History

Published 21 Jul 2023In 1937 Japan invaded the Republic of China after already annexing Manchuria in 1931. With the international settlements in Shanghai, the military support through Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and the general escalation of the war, many argue that 1937 marked the start of the Second World War in Asia.

(more…)

July 18, 2023

Manville Gas Gun

Forgotten Weapons

Published 29 Oct 2012Charles Manville developed this weapon in the 1930s as a riot control tool, and they were built in 12ga, 25mm, and 37mm. We should point out that the 12ga version was for tear gas rounds only (like today’s 12ga flare launchers) and not safe to use with high-pressure ammunition. Anyway, it was intended for use by prison guards and riot police, offering a much greater ammunition capacity than any other contemporary launcher.

During World War II, Manville tried to sell the military on a high-pressure version to fire 37mm explosive rounds, but was unsuccessful. Instead, the Manville company spent the was making parts for the Oerlikon 20mm AA guns, and the tooling for the gas launcher was all destroyed.

(more…)

June 28, 2023

The Treaty of Versailles: 100 Years Later

Gresham College

Published 4 Jun 2019The Treaty of Versailles was signed in June 1919. Did the treaty lead to the outbreak of World War II? Was the attempt to creat a new world order a failure?

A lecture by Margaret MacMillan, University of Toronto

04 June 2019 6pm (UK time)

https://www.gresham.ac.uk/lectures-an…A century has passed since the Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. After WWI the treaty imposed peace terms which have remained the subject of controversy ever since. It also attempted to set up a new international order to ensure that there would never again be such a destructive war as that of 1914-18. Professor MacMillan, a specialist in British imperial history and the international history of the 19th and 20th centuries, will consider if the treaty led to the outbreak of the Second World War and whether the attempt to create a new world order was a failure.

(more…)

June 13, 2023

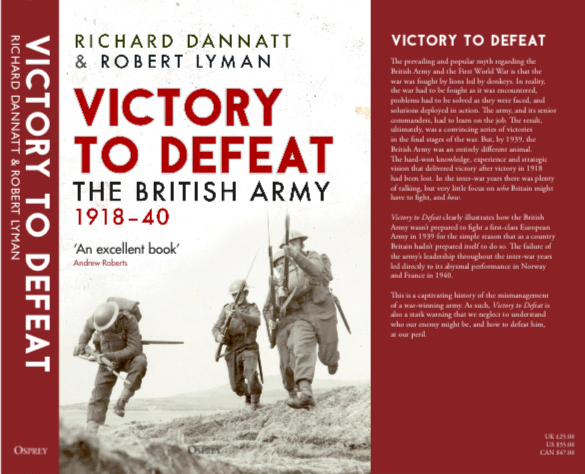

After the Great War, the British army failed to plan for future conflicts

Robert Lyman outlines why Britain in general and the British army in particular were so materially and intellectually unready for the war that broke out in 1939:

… the British Army was catastrophically unprepared for war in 1939. But it wasn’t just the Army that was unprepared. Despite a last-minute rush to re-arm, so too was the whole country. In Britain a deep-seated passivity had set in following the end the Great War. This belied the reality that in Europe the ending of the war in fact opened the door to unheralded political chaos and instability that was in time to overcome the forces of stability and would lead directly to yet another devastating war. In the years immediately following the arrival of peace in 1918 Britain hoped it could close the door on any future European or continent commitment and return to the halcyon days when its only security commitments were the defence of its widely flung Empire.

The weakness at the heart of British planning for war was a direct reflection of Britain’s strategic, political, societal and economic situation during the inter-war period. Britain – both the British public and the country’s various governments – simply wasn’t mentally prepared to go to war again so soon after the trauma of the Great War. As a result, it made no proper preparation for another full-on industrial war against a peer opponent on the continent. This was fundamentally a failure of political and military imagination; the inability to think through what a potential war might look like and to prepare for this possibility accordingly.

We have identified five primary causes of the decline of British military effectiveness in 1939. In the first place there was no clear strategic plan for the Army. Strategies are determined by having a clear understanding of who a future enemy might be. Following the end of the Great War, until the late 1930s no one seemed bothered to define this essential point of direction. There was a remarkably inadequate grand strategic conversation (i.e., at a national, governmental level) about the purpose, structure, and nature of the Army. There was plenty of talking, but very little of it focused on realistic determination as to who it might have to fight, and how. This was a problem, because it meant that Britain was unable to determine the precise structure its armed forces needed to be, and its cost. Was the focus of the army to be the continent, or the Empire, or both? No one knew. As a result, the last known plan reasserted itself – Imperial defence, à la 1914. This meant that the army wasn’t structured or equipped to fight a specified enemy in a defined set of circumstances. Instead, the British Army and its cousin, the Indian Army, was expected to be a generic jack-of-all-trades, without the structure, doctrine, training, or equipment to fight the type of war it had become the master of in 1918. While there was some doctrine, and considerable doctrinal debate, little was anchored in a clear definition of what future war was expected to look like. There was no operational design for the British Army derived directly from an analysis of the threat it faced. If it had done, the BEF would have been thoroughly prepared for the German Blitzkrieg in France and the Low Countries in 1940 or the similar Japanese Kirimoni Sakusen in 1941 and 1942. The British Army wasn’t prepared to fight a first-class European Army in 1939 for the simple reason that Britain hadn’t prepared itself to do so. Likewise, when it came to fighting the Japanese in 1941 and 1942 in Malaya and Burma, the British found that not only had it failed to prepare adequately for a potential Japanese invasion of its vulnerable Far Eastern colonies, but that it had no idea as to how to fight the Imperial Japanese Army. There were two connected failures here. The first was one of strategic preparedness, the blame for which was both governmental and strategic. The second was of training, doctrine and military preparedness by the British Army in Europe and Asia to fight. When they emerged out of their assault boats at Kota Bahru on the morning of 8 December 1942 the Japanese could as well have come from Mars, given how little the British knew about them and their warfighting methods.

Second, as a country, Britain was unprepared both politically and culturally for another war so soon after the last. In 1919 the country seemed to want to look backward to embrace the days of peace that had preceded the cataclysm of war, to drape itself with Edwardian comfort. It was tired and disillusioned, and felt no victor’s triumph. The country looked to itself, and to its Empire, eschewing the complications of commitments on continental Europe that had recently resulted in the loss of so much blood. The losses sustained in the Great War resulted in the overwhelming national sentiment that war must never again be undertaken as a form of politics. Clausewitz was dead. Part of this sentiment evidenced itself in the rise of pacifism. In the army, a pervasive belief existed that the Great War was an aberration, and nothing like it would again afflict western civilisation. Any lessons from the war were therefore irrelevant to the future structures or doctrine of the British Army, for whom the defence of the Empire was the crucial issue. But whether it liked it or not, the world was changing fast, in ways that Britain struggled to comprehend and from which it could not ultimately escape. The Russian Revolution, the rise of fascist dictators in Europe, isolationism in the USA (except for a new American assertiveness in Asia) and the increasing militancy of Japan, began changing the global landscape in ways that were hard to understand for a country seemingly once in total charge of the certainties of statecraft. Now it struggled to find its way in a new world of tension, turmoil and rapid change.

Third, no one in the British Army thought to capture the reasons for operational success in 1918. The dramatic reduction in troops numbers at the end of the Great War meant that those best able to convert the learning from 1918 into doctrine left for civilian life, taking their knowledge and experience with them. It was never recovered. There was therefore no template in the years afterward on which to build a successful military doctrine based on the successful warfighting experience that had culminated in the victories of 1918.

Fourth, political naivety led to a dramatic economic stringency being applied, including the underlying Treasury assumption in the early 1920’s of the ‘Ten Year Rule’, an assumption that kept rolling over, year after year. This meant that there wasn’t enough money to do what was necessary to protect British interests from impending harm. The Army butter was thinly spread on the imperial bread, with the result that insufficient investment was made in the core of the army’s warfighting capability. This stringency was exacerbated by the impact of the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s into the early years of the next decade.

May 24, 2023

Darne Model 1933: An Economic & Modular Interwar MG

Forgotten Weapons

Published 15 Feb 2023The Darne company was one of relatively few private arms manufacturers in France, best known for shotguns. During World War One they got into the machine gun trade, making licensed Lewis guns for the French air service. After making a few thousand of those, Regis Darne designed his own belt-fed machine gun in 1917. A large order was placed by the French military, but it was cancelled before production began because of the end of the war.

Darne continued to develop this design in the 1920s, while also producing sporting arms to keep the business running. The gun was intended mostly as an aircraft gun, but designed in a rather modular fashion, easily made into both magazine-fed and belt-fed infantry versions as well as downing, wing, and observer aerial models. It was actually bought by the French Air Force, as well as several other countries during the inter-war period.

The example we are looking at today is an infantry configuration, with a bipod and light-profile barrel. It is chambered for the French 7.5x54mm cartridge, and is officially the Model 1933 (one of the last iterations made).

(more…)

May 17, 2023

Swiss LMG25 light machine gun

Forgotten Weapons

Published 23 Jul 2012This week, we will be featuring all Swiss weapons here at Forgotten Weapons. Kind of like Shark Week, but more land-locked. We’ll kick off today with a video showing you around a Swiss LMG-25 light machine gun we found for sale at Cornet & Company in Brussels (a better gun shop than any I’ve found here in the US, I must say). Like pretty much all Swiss arms, it’s a gorgeous example of precision machining — and like pretty much all Swiss arms it was too expensive for anyone else to adopt. On this, as with other Swiss weapons I’ve handled, you can just feel the quality in how smoothly the moving parts operate.

In case you’re wondering, this LMG25 is live and fully functional, and priced at 1950 Euros (about $2800) — mere pocket change compared to machine gun prices here. It’s not too difficult to get the permit to own it in Belgium, but sadly there is no legal way to bring it into the US.

(more…)

May 6, 2023

Coronation Weekend

Jago Hazzard

Published 5 May 2023For us train nerds, “Coronation” means something very different.

April 24, 2023

Pedersen Selfloading Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Nov 2014When the US military decided to seriously look at replacing the 1903 Springfield with a semiautomatic service rifle, two designers showed themselves to have the potential to design an effective and practical rifle. One was John Garand, and the other was John Pedersen. Pedersen was an experienced and well-respected gun designer, with previous work including the WWI “Pedersen Device” that converted a 1903 into a pistol-caliber semiauto carbine and the Remington Model 51 pistol, among others.

Pedersen’s rifle concept used a toggle locking mechanism similar in concept to the Borchardt and Luger pistols, but designed to handle the much higher pressure of a rifle cartridge. Specifically, the .276 Pedersen cartridge, which pushed a 125 grain bullet at about 2700 fps. Both Pedersen’s rifle and the contemporary prototypes of the Garand rifle used 10-round en bloc clips of this ammunition.

Ultimately, Pedersen lost out to Garand. Among the major reasons why was that his toggle action was really a delayed blowback mechanism, and required lubricated cartridges to operate reliably. Pedersen developed a hard, thin wax coating process for his cartridge cases which worked well and was not prone to the problems of other oil-based cartridge lubricating systems, but Ordnance officers still disliked the requirement. This combined with other factors led to the adoption of the Garand rifle.

After losing out in US military trials, Pedersen still had significant world-wide interest in his rifle, and the Vickers company in England tooled up to produce them in hopes of garnering contracts with one or more other military forces. About 250 rifles were made by Vickers, but they failed to win any contracts and production ceased — making them extremely rare weapons today.

Pedersen lived until 1951, and was well regarded for his sporting arms development with Remington — none other than John Moses Browning described him as “the greatest gun designer in the world”.

(more…)

April 22, 2023

The Big Four

Jago Hazzard

Published 1 Jan 2023It’s 100 years since the Grouping – what happened, why and how?

(more…)

April 19, 2023

The USMC finds a new mission after WW1

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry (unpublished, but serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook:

The 1919 demobilization was nearly as traumatic for the Marines as it was for the Army. Their numbers fell from a peak of 75,000 to about 1,000 officers and 16,000 enlisted in 1920. Authorized strength was 17,400. The 15 Marine regiments and at least three, probably four, machinegun battalions existing at the end of November 1918 had withered away to only five regiments and a couple of separate battalions (one artillery and one infantry) by the following August.

Marine commitments, however, remained heavy. The brigades in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic had their hands full suppressing new rebellions. Guard detachments were still needed for Navy bases and Navy ships. The number of men required for the latter duty had fallen by only 10% since 1918. The Marines also had to staff their own bases at Quantico, Parris Island, and San Diego and they had to find men to rebuild the advance base force as well. When these facts were brought to the attention of Congress in 1920 the latter increased the Marine Corps’ authorized strength to 1,093 officers and 27,400 enlisted but then approved funding for only 20,000.

[…]

The bulk of the Corps’ operating forces were still engaged in colonial police work in the Caribbean. However, the new Commandant, Major General John A. Lejeune, was prescient enough to realize that this would not last and that a much more permanent mission would be needed to secure his service’s future. Instead, Lejeune and his advisors concluded that the real mission of the Marine Corps was “readiness”. While this concept might seem trite, one should consider that the United States was and is primarily an insular power. Its standing army in 1920 served primarily as a garrison force and cadre for a much larger wartime citizen army. Little or none of it would be available for immediate use upon the outbreak of a major war beyond the troops already deployed to major US overseas possessions like the Philippines, Hawaii, or the Panama Canal.

Although the Army of 1920 seemed to have little idea about who its future adversaries were likely to be, the Navy had already fingered Japan as its most likely future opponent. Japan had the most powerful navy after the United States and Great Britain and Japanese-American animosity was growing. The Japanese resented the treatment of Japanese immigrants in California. Americans resented Japan’s high handed actions in China. The Japanese saw American criticism of Japan’s China policy as interference in Japan’s rightful sphere of influence. Any war fought against Japan would be primarily naval in character. However, post war disarmament treaties forbade improvements to any American fortresses west of Hawaii. The League of Nations had also mandated most of the central Pacific islands to Japanese control.

If it was to successfully engage the Japanese fleet, or to threaten Japan itself, the United States Navy would need bases in those central Pacific islands. Hawaii was too far away to be useful and the Philippines were too vulnerable to Japanese attack. Only an expeditionary force could seize and hold the central Pacific islands that the Navy needed and that expeditionary force would have to be ready to move whenever and wherever the Navy did. By staying “ready”, requiring only limited reserve augmentation and, being already under the Navy’s control, the Marine Corps would be much better positioned than the Army to provide this expeditionary force, at least during the critical early stages of the next war.*

* Heinl op cit pp. 253-254; Moskin op cit pp. 219-222; and Clifford op cit pp. 25-29 and 61-64.

April 17, 2023

April 1, 2023

QotD: P.G. Wodehouse and Sir Oswald Mosley

The majority of his tales are set in country houses, replete with conservatories, libraries, gun rooms, stables and butler’s pantries. Letters arrive by several posts a day, telegrams by the hour. Trains run on time from village stations. Other than the pinching of policemens’ helmets, there is order and serenity. Necklaces are filched, silverware is purloined, butlers snaffle port, chums are impersonated, romances develop in rose gardens, but nothing lurks to fundamentally reorder society.

There was one exception. The object of Wodehousian scorn was the moustachioed leader of Britain’s black-shirted Fascists, Sir Oswald Mosley, 6th Baronet. A fencing champion at school, dashing war record in the Flying Corps, and a Member of Parliament, he was the recipient of an inherited title, with a family tree that stretched back to the 12th century, a country house and a Mayfair residence. In Wodehouseland, Mosley is transformed into the equally aristocratic Roderick Spode, 7th Earl of Sidcup.

Plum was intolerant of even the vaguest of threats to the established order of things. He voiced his dislike of Spode through Bertie Wooster, likening the fascist leader to one of “those pictures in the papers of dictators, with tilted chins and blazing eyes, inflaming the populace with fiery words on the occasion of the opening of a new skittle alley”. Plum focussed his gaze on the Spode/Mosley moustache, which was “like the faint discoloured smear left by a squashed black beetle on the side of a kitchen sink”, describing its owner as “one who caught the eye and arrested it”.

The proto-dictator appeared, thought Wodehouse, “as if Nature had intended to make a gorilla but had changed its mind at the last moment”. Every reader would have known it was Mosley in the crosshairs, because Spode was the leader of a fascist group called the “Saviours of Britain, also known as the Black Shorts”. The transition of attire is because, as another of Wodehouse’s masterful creations, Gussie Fink-Nottle, observed, “by the time Spode formed his Association, there were no black shirts left in the shops”.

A different Wodehouse character warned, “Never put anything on paper … and never trust a man with a small black moustache.” Indeed, anyone “whose moustache rose and fell like seaweed on an ebb-tide” was best avoided. Plum could have been referring to Mosley or Hitler. The former, as leader of Britain’s real-life black shirts, was an unashamed admirer of the latter, and he interned in Holloway prison during the war. Afterwards, as an advocate of what we today would call Holocaust denial, he moved to Paris where he died in 1980. His political journey was interesting. Mosley started as a Conservative, drifted leftwards into the Labour Party, then further left into his own independent party, which evolved into the right-wing British Union of Fascists.

Modelled on the Italian and German fascist movements, Mosley and his supporters came to believe that “Jewish interests commanded commerce, the Press, the cinema, dominated the City of London, and killed British industry with their sweatshops”. Fascism lurking in the upper classes troubled Plum Wodehouse so greatly that Spode and his Black Shorts appeared in five of his works between 1938–74.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Coups and coronets”, The Critic, 2022-12-13.

March 27, 2023

Why Russia Lost the Polish-Soviet War

The Great War

Published 24 Mar 2023

The Polish-Soviet War was one of the most important conflicts in the aftermath of the First World War when Eastern Europe was in flux. Both the Polish and the Bolshevik Army had the advantage numerous times and at the Battle of Warsaw is looked like the Bolsheviks would carry the revolution into Western Europe.

(more…)