On Substack, Fergus Mason updates us on what’s happening around the UK/US military base on Diego Garcia in the Chagos Islands in the Indian Ocean:

One of the great mysteries of Keir Starmer’s government is why he’s so determined to give the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, which is 1,200 miles away and has never owned them. Even now, as he desperately fights for his political survival, Starmer is pushing ahead with plans to give away the strategic archipelago then pay tens of billions of pounds to lease back one of the islands. It’s an odd thing to be so focused on — but whether his compulsion to surrender the islands is driven by corruption or naivete, it’s sending out signals of weakness. And those signals are being noticed.

The Maldives Makes A Grab

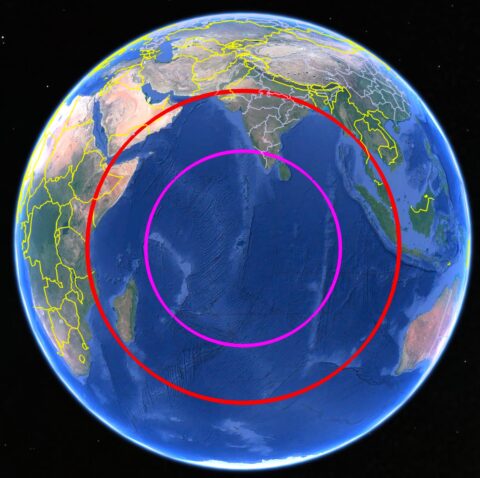

Last Thursday the Republic of Maldives announced that it had rejected the UN International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea’s ruling on its maritime boundaries, and sent an armed boat to carry out a “special surveillance operation” in the northern part of the Chagos island’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The Chagos EEZ is claimed by Mauritius, but of course actually belongs to Britain until Starmer’s surrender deal is approved by Parliament. However, the Maldivian government has now decided to make its own claim on the area — and it’s very publicly doing something about it. The “coast guard vessel” CGS Dharumavantha — a former Turkish Navy fast attack craft — is now operating in the area, along with drones from the Maldives National Defence Force Air Corps.

Of course, the Maldives has no real claim to the Chagos islands or any part of their waters. The country — a tiny group of islands southwest of Sri Lanka, with a land area of just 115 square miles — was a British crown colony from 1796 to 1953, and a British protectorate until 1965. Like Mauritius, it has never owned the Chagos Islands. However, it’s just 300 miles away from them, much closer than Mauritius. It appears that its leader, President Mohamed Muizzi, has decided that if the key British territory is up for grabs the Maldives should be the ones to grab it. It’s true the Maldives doesn’t have much of a navy, but then Mauritius doesn’t have much of a navy either and is a lot further away. If the Maldives can seize control over part of the extremely valuable Chagos Marine Protected Area (MPA), and even possibly some of the northern islands, there isn’t a lot Mauritius can do about it.

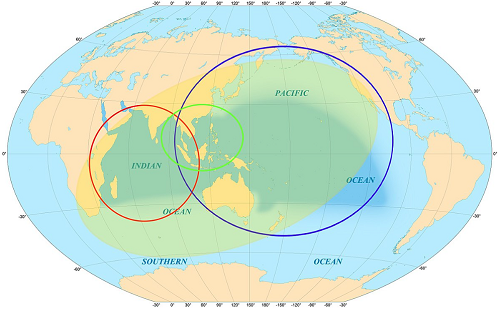

Why would the Maldives be so keen to seize part of the Chagos EEZ? That one’s simple. Under British protection, the Chagos MPA (which is the largest marine nature reserve in the entire world) has been officially off limits to commercial fishing since 2010 but, in practice, has barely been fished at all since 1968. This makes it a unique and potentially lucrative resource in the Indian Ocean region, which has seen its ecosystems devastated by destructive fishing methods. The wealth of the MPA is the main reason Mauritius wants the Chagos islands. Its own coastal waters have been blighted by overfishing, including the destruction of coral reefs by explosives and bleach injection, and now it wants to plunder the MPA. The Maldives is also busily engaged in destroying its own fish stocks (fishing is the country’s largest industry and employs half the population) and is desperate for new waters to pillage. They don’t just want access for their own boats, either. Like Mauritius, the Maldives under Muizzi’s rule is an increasingly close ally of China.

The Scourge Of The Seas

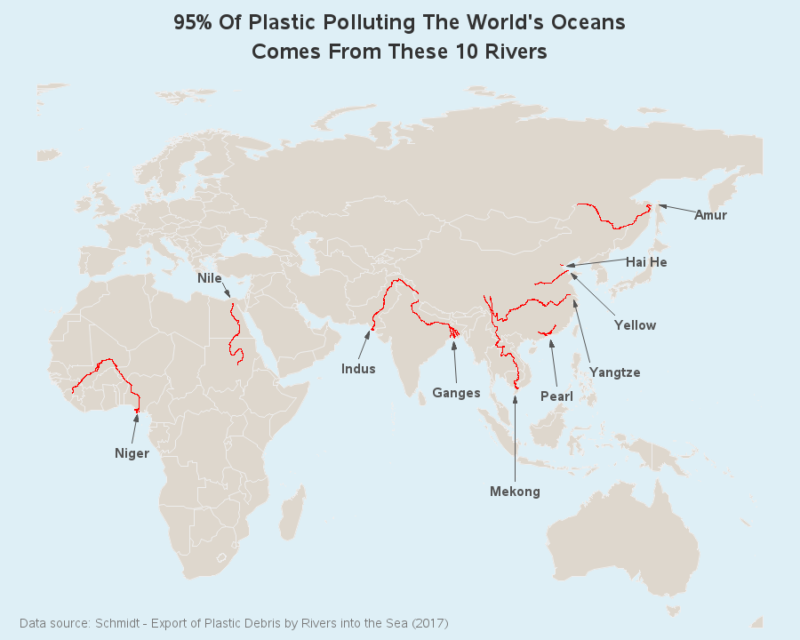

China has the world’s largest fishing fleet, and it’s not even close. Over 44% of all commercial fishing is carried out by Chinese boats — and they’re notorious for flouting international law. Chinese boats regularly change their names and disable their satellite tracking systems to conceal their identity, then fish illegally in other countries’ waters. They violate quotas, catch protected species and strip whole swathes of ocean clean of any life much larger than plankton with massive, indiscriminate drift nets. Chinese fishing boats have also been implicated in people trafficking, drug smuggling and acting as spying and covert action platforms for the Chinese navy.

If either Mauritius or the Maldives gain control of the Chagos MPA it’s a certainty they will immediately give Chinese boats access, and this priceless nature reserve will rapidly be trawled and drift-netted into a barren, lifeless wasteland. From China’s point of view, of course, it doesn’t matter which of their lackeys takes over the Chagos islands as long as one of them does, so don’t expect them to step in to help Mauritius. They don’t care who they get the fishing rights from.