Atun-Shei Films

Published 22 Nov 2019Thanks to Indiana Jones, everybody knows that German archaeologists in the 1930s were searching for occult ancient artifacts … but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. In this educational video, I explore how the N@zis turned the discipline of prehistoric archaeology into a cog in their propaganda machine, and how their crazy conspiracy theories about lost civilizations continue to haunt us to this day.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (All donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

Buy Merch ► teespring.com/stores/atun-shei-films

#WW2 #Archaeology #History

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

January 29, 2021

Ancient Aryans: The History of Crackpot N@zi Archaeology

January 3, 2021

Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon ranks with Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

James E. Hartley on why Koestler’s 1941 novel should be seen as a prescient guide to modern-day “wokeness”:

The puzzling thing about wokeness is not that it is fashionable among a small subset of the Campus Left. One should never be surprised by what is fashionable among college faculty and students. The curious question is how these ideas broke out of the academic asylum and met acquiescence among a large group of people who should have known better.

The answer is found in a book which should have never fallen off the radar: Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. First published in 1941, it was — along with 1984 — one of the great books about totalitarianism written in the 1940s. Widely praised when it was published, the book was enormously influential in fostering the consensus view of post-war anti-communism. In 1998, Modern Library published a list of the 100 best English novels of the 20th century; Darkness at Noon was ranked eighth, five places above 1984.

The plot of the novel itself is fairly simple. The story begins with the imprisonment of Nicholas Rubashov, one of the heroes of the communist revolution in a country which is clearly the Soviet Union. Decades after the revolution, Number 1 (read: Stalin) has assumed power. Rubashov is imprisoned on the absurdly false charges of plotting to kill Number 1. The entire novel takes place in prison, as Rubashov is interrogated and eventually comes to voluntarily confess at a public trial to crimes he did not commit. He is then shot.

The novel explores the philosophical puzzle of why Rubashov would join with what has obviously become a murderous cult run by a totalitarian who is solely interested in amassing enough power to stamp his will upon the whole country. Rubashov, a devoted communist to the end, abandons his principles and bit by bit comes to accede to demands of the new generation who are seeking scapegoats and ritualistic confessions of guilt.

What is the nature of the new generation? One of the Party officials interrogating Rubashov explains:

There are only two conceptions of human ethics, and they are at opposite poles. One of them is Christian and humane, declares the individual to be sacrosanct, and asserts that the rules of arithmetic are not to be applied to human units. The other starts from the basic principle that a collective aim justifies all means, and not only allows, but demands, that the individual should in every way be subordinated and sacrificed to the community — which may dispose of it as an experimentation rabbit or a sacrificial lamb.

The individual does not matter. The group matters. What is good for the group is by definition good, regardless of whether it is good for the individual. As the interrogators make abundantly clear, no individual has the right to stand in the way of the group. The Party represents the group, and thus no individual has the right to oppose the Party.

November 30, 2020

November 14, 2020

QotD: “Modern” liberalism

All of this became “dated,” as I grew older. My first shocking discovery about the “modern” liberal is, that while he might give lip-service still to some “antiquated” ideals, and gratuitously pose as virtuous, his first instinct when faced with serious responsibility was to cut and run.

My second was to find that he was now brainwashed by ideologies and slogans; that it was impossible to argue with him from reason or fact; that faced with any difficulty he would present himself as the helpless victim of forces he would not even try to define coherently.

My third was the discovery that he was now, instinctively, on the side of the criminal; that he identified with the lawless; that he admired “the transgressive,” trespass, violation. Without acknowledging it to himself, he now had a conception of “human rights” which consistently excused the wrongdoer, and consistently ignored the consequences to those who had done nothing wrong.

This “modern” liberalism, I came to understand, was the development — not over months and years but over centuries — of a mortal flaw in the “classical” liberal worldview. It was avoiding God. The liberal mind was persuaded that humans must “make their own beds.” Its great strength was that it took responsibility; its great weakness was that it had no reason to do so. Faith and reason are mutually dependent; when one goes the other eventually goes, too.

Or put this another way: the Devil gets in when we make room for him.

David Warren, “Crime without punishment”, Essays in idleness, 2018-08-03.

November 8, 2020

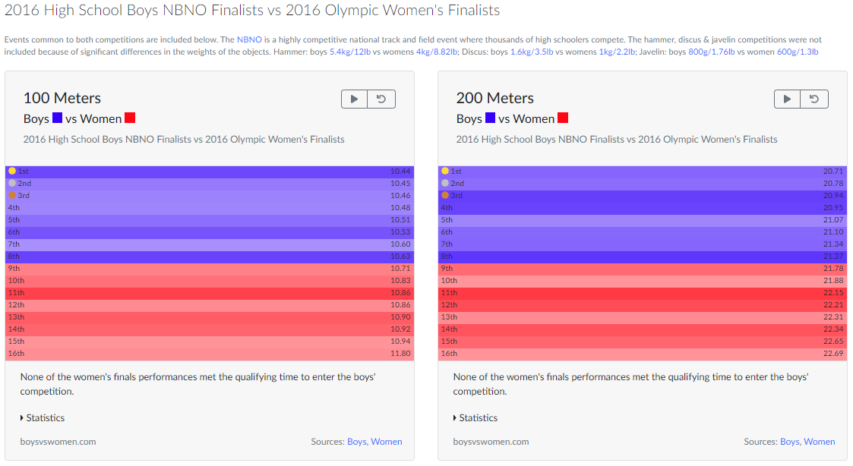

“… participants in men’s sport, on average, out-perform participants in women’s sports, current science is unable to isolate why this is the case”

Barbara Kay is not in favour of clearly misogynistic sports policies:

No hormone treatment is required, says the EWG, because being male or female is not dependent on biology but on one’s feelings: “(It) is recognized that transfemales are not males who become females. Rather these are people who have always been psychologically female.” Furthermore, these individuals must be allowed to participate in “the gender with which they feel most comfortable and safe, which may not be the same in each sport or consistent in subsequent seasons.” Your eyes do not deceive you. First they justified trans women competing with women because they had “always” felt they were female. Then they say the “always” female trans athlete might “be” male for certain sports or at different times.

It gets worse.

They say that although “participants in men’s sport, on average, out-perform participants in women’s sports, current science is unable to isolate why this is the case.” This is nonsense on two counts. First, there is no “on average” about it. Virtually all high-performance male athletes out-perform all high-performance female athletes. And second, even in 2014, abundant scientific data “to isolate why this is the case” was readily, even effortlessly (#Google!) available.

Data or no data, a statement in the document itself makes clear that the ideological fix was in from the get-go: “The Expert Working Group held strongly to the principle that the inclusion of all athletes, based on the fundamental human right of gender self-determination overrides any consideration of potential competitive advantage.”

Needless to say, but it must be said anyway: Male athletes have nothing whatsoever to fear in competing with trans male athletes. This is a problem for female athletes only, which seems not to trouble the CCES at all. I’m not a feminist, but I know a misogynistic sport policy when I see it. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

September 15, 2020

Critical Race Theory

Dan Sanchez, Tyler Brandt, and Brad Polumbo discuss President Trump’s recent Executive Memo banning the use of federal government funds for Critical Race Theory training:

Critical Race Theory is a branch of Critical Theory, which began as an academic movement in the 1930s. Critical Theory emphasizes the “critique of society and culture in order to reveal and challenge power structures,” as Wikipedia states. Critical Race Theory does the same, with a focus on racial power structures, especially white supremacy and the oppression of people of color.

The “power structure” prism stems largely from Critical Theory’s own roots in Marxism — Critical Theory was developed by members of the Marxist “Frankfurt School.” Traditional Marxism emphasized economic power structures, especially the supremacy of capital over labor under capitalism. Marxism interpreted most of human history as a zero-sum class war for economic power.

“According to the Marxian view,” wrote the economist Ludwig von Mises, “human society is organized into classes whose interests stand in irreconcilable opposition.”

Mises called this view a “conflict doctrine,” which opposed the “harmony doctrine” of classical liberalism. According to the classical liberals, in a free market economy, capitalists and workers were natural allies, not enemies. Indeed, in a free society all rights-respecting individuals were natural allies.

Classical Race Theory arose as a distinct movement in law schools in the late 1980s. CRT inherited many of its premises and perspectives from its Marxist ancestry.

The pre-CRT Civil Rights Movement had emphasized equal rights and treating people as individuals, as opposed to as members of a racial collective. “I look to a day when people will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character,” Martin Luther King famously said.

In contrast, CRT dwells on inequalities of outcome, which it generally attributes to racial power structures. And, as we’ve seen from the government training curricula, modern CRT forthrightly judges white people by the color of their skin, prejudging them as racist by virtue of their race. This race-based “pre-trial guilty verdict” of racism is itself, by definition, racist.

The classical liberal “harmony doctrine” was deeply influential in the movements to abolish all forms of inequality under the law: from feudal serfdom, to race-based slavery, to Jim Crow.

But, with the rise of Critical Race Theory, the cause of racial justice became more influenced by the fixations on conflict, discord, and domination that CRT inherited from Marxism.

Social life was predominantly cast as a zero-sum struggle between collectives: capital vs. labor for Marxism, whites vs. people of color for CRT.

September 13, 2020

“Systemic racism” in Canada

At The Line, a useful examination of what is meant in the Canadian context by the term “systemic racism”:

Can we go back one step? “Systemic racism.” Let’s start there: which system? The legal system? Our social welfare system? The policing system? The media? Our corporations? All of human society? Are we talking about Canadian society, or North American society as whole? Are there geographic limits to the systems we’re talking about? Is China systemically racist?

Let’s break this down further: what definition of “racism” are we using? Are we using the old definition whereby any bigotry based on skin colour is “racist”? Or are we engaging the new definition, where “racism” is an expression of structural power — and, therefore, only white people can be racist because only they hold structural power?

It’s impossible to fix a problem if we can’t come to a common understanding about plain meanings of the terms we are using. Vague in, vague out.

There are many statements of “systemic racism” that we, at The Line, would have no qualms agreeing with, i.e.; “The Indian Act is a clear example of systemic racism in Canadian law.” That isn’t a controversial position — but it also isn’t an unclear one. Asserting a belief in “systemic racism” sounds like a broadly agreeable thing to do, but the term is loaded with meaning and ideological baggage that is not immediately apparent.

Take, for example, a claim that Canadian society is systemically racist because it is structured at all levels to favour white dominance — and that any disparity of outcome between racial groups is proof of that fact. Well, that’s a much more all-encompassing ideological position, isn’t it? There’s a perfectly legitimate framework for critique in here, but there’s also a lot to unpack.

It’s easy to find legitimate examples of systemic racism while leaving the actual meaning and implications of the term both vague and tautological. But if we’re going to use statement of belief in “systemic racism” as some kind of litmus test for political acceptability, the clear meaning of the term matters.

In the absence of that clarity, using it as a gotcha question and backing people in public life into reciting this stuff as if it were some kind of statement of faith comes off as not a little creepy.

August 16, 2020

QotD: Labour is now the “party of government” even when they’re not in power

Labour, it seems to me and to many others I’m sure, has mutated from once upon a time being the party speaking for the poor, often against the government, to being the party of government, even when they aren’t the politicians in titular charge of that government. These people are now “supportive of the state”, to quote Hartley, even when they’re not personally in charge of it. It’s the process of government, whoever is doing it, whatever it is doing, that they now seem to worship. It is, as similar people in earlier times used to say, the principle of the thing, the principle being that they’re in charge. Many decades ago, Labour spoke for, well, Labour. The workers, the toiling masses. Now they represent most determinedly only those who labour away only in Civil Service offices or their allies in the media, in academia, and in the bureaucratised top end of big business.

Anyone official and highly educated sounding who challenges whatever happens to be the prevailing supposed wisdom of this governing class, on Coronavirus or on anything else, must be scolded into irrelevance and preferably silenced. The governors must be obeyed, even if they’re wrong. In fact especially if they’re wrong, just as the soldiers of the past were expected to obey their orders, no matter what they thought of the orders or of the aristocratic asses who often gave them. Whether they were good orders was an argument that those giving orders could have amongst themselves, but that orders must be obeyed was a given. “Capitalism” isn’t worth dying for, but this new dispensation is, right or wrong.

Our new class of entitled asses, together with all those who have placed their bets for life on carrying out their orders or trying to profit from them, seems now to be the limit of the Labour Party’s electoral ambition. And who knows? The awful thing is that this class and its hangers-on could be enough, in the not too distant future, to get them back into direct command of the governmental process that they so adore.

Brian Micklethwait, “Mick Hartley on the politics of the Lockdown”, Samizdata, 2020-05-15.

July 31, 2020

Xi Jinping and the “Chinese dream”

Zineb Riboua outlines possible ways for the West to counter ongoing Chinese economic espionage:

President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping at the G20 Japan Summit in Osaka, 29 June, 2019.

Cropped from an official White House photo by Shealah Craighead via Wikimedia Commons.

Since 2012, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s favourite catchphrase has been “the Chinese dream”. In stark contrast to the evil, capitalistic American dream, Xi’s alternative vision of progress teaches that the only route to prosperity is through rigid adherence to collectivist ideology.

The Chinese state embodies a very particular ideology. Over the last few decades, it has aggressively ramped up its economic and political capital through business and enterprise, inextricably tying itself to the economic fortunes of both developed and developing countries. It is now seeking to use the economic capital it has accumulated to force its political agenda into reality.

That is why the role of private companies in China is unparalleled. Milton Friedman defined corporate social responsibility in terms of private companies’ sole duty to make a profit, and then increase that profit. Chinese companies appear to be exempt from this rule because they interact with the state in a unique and troubling way.

The current state of the Chinese political and economic landscape is no accident. When Deng Xiaoping spoke in the 1980s of building a “socialism with Chinese characteristics”, this is probably exactly what he had in mind. The Chinese Communist party has succeeded in weaponising local market forces in such a way that it now holds all the cards in its nation’s dealings with the outside world, both political and economic, because the line between the public and the private is non-existent.

This strategy has not gone unnoticed. Thanks to the Chinese Communist party’s recent conduct – unprecedented aggression in Hong Kong, the appalling genocide of the Uyghur people and a costly unwillingness to share information relating to the coronavirus outbreak – the state of its internal affairs has come into sharp focus on the international stage.

Unsurprisingly, the hawkish US has placed itself at the forefront of counter-Chinese rhetoric. Secretary of state Mike Pompeo said recently: “We gave the Chinese Communist party and the regime itself special economic treatment, only to see the CCP insist on silence over its human rights abuses as the price of admission for Western companies entering China.”

July 29, 2020

The Equity, Inclusivity, and Diversity Industrial Complex

In The Dominion, Ben Woodfinden comments on a Ross Douthat column on the “antiracist” demands of our modern protestariat (the hordes of un- or under-employed university-educated young liberals and socialists):

University College, University of Toronto, 31 July, 2008.

Photo by “SurlyDuff” via Wikimedia Commons.

… the most interesting aspect of this lockdown-induced outpouring of collective rage hasn’t been the protests, or the cancellations, but the woke job creation that is going on. The ideology behind things like “white fragility” is increasingly being transformed into what can be described as an equity-inclusivity-diversity (EID) industrial complex that might end up being the most significant long term structural change that emerges out of the protests.

One of the most common responses in elite institutions as they promise to address systemic racism has been the creation of new jobs and positions that will supposedly help to do so. For instance, the Washington Post created a set of new positions that will be focusing on racial issues. This included hiring a “Managing Editor for Diversity and Inclusion.” At Princeton, the administration announced, like many other elite universities, new courses (which means new teaching opportunities) focused on racial injustice, as well as new projects and funding for research to explore and address racial issues. Stanford has created a new Centre for Racial Justice at its law school.

This direct job creation is just the tip of the iceberg. The real EID industrial complex is in the creation of a vast number of new jobs dedicated to the promotion and advancement of the basic tenets of this ascendant ideology through the expansion of human resource departments to deal with these issues, the creation of new EID bureaucrats and administrators in universities, corporations, government departments, the rise of EID consulting and mandatory courses and workshops for employees, new jobs and potential litigation for lawyers, as well as courses and modules in law schools to teach aspiring lawyers about these things.

In the bestselling Ibram X. Kendi book How To Be An Antiracist, one of Kendi’s central solutions is to pass an anti-racist amendment to the U.S. Constitution and permanently establish and fund a Department of Anti-racism. This department:

would be comprised of formally trained experts on racism and no political appointees. The DOA would be responsible for preclearing all local, state and federal public policies to ensure they won’t yield racial inequity, monitor those policies, investigate private racist policies when racial inequity surfaces, and monitor public officials for expressions of racist ideas. The DOA would be empowered with disciplinary tools to wield over and against policymakers and public officials who do not voluntarily change their racist policy and ideas.

The radical tendencies of the bourgeois bolsheviks in the streets might make them seem like true revolutionaries, but what this movement seems to actually want to create, with remarkable success, is new employment opportunities for true believers in the new anti-racist creeds. Racism won’t so much be solved by tearing society down, but by massively expanding new professional and managerial jobs that can guarantee full employment for the credentialed class of true believers.

O’Boyle’s thesis is that the revolutions that swept across European cities in 1848 were because a large surplus of resentful and overeducated men felt society was denying to them what they were rightfully owed. O’Boyle looks at Germany, where university education was cheap, and was “emphasized as an avenue to wealth and power.” This ending up producing an excess of ambitious, but resentful and frustrated men who felt society was not allotting them the status and comfort they deserved. The same was true in France. But in Britain, the opportunities produced by industrialization that had yet to fully materialize on the continent kept this excess surplus of overeducated men much smaller, and helped insulate Britain from revolution.

What if the EID industrial complex actually helps to reduce the scarcity of opportunities in elite fields and institutions that will put a lid on the unrest that overproduction breeds? The EID industry is worth billions of dollars, and in a way it might be the solution liberalism offers to both the radical progressivism of this ideology, and to the challenge posed by elite overproduction.

July 18, 2020

“Agglomerationists” today and in the Middle Ages

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes compares the views of today’s “urbanists” with the “agglomerationists” of the late Medieval period:

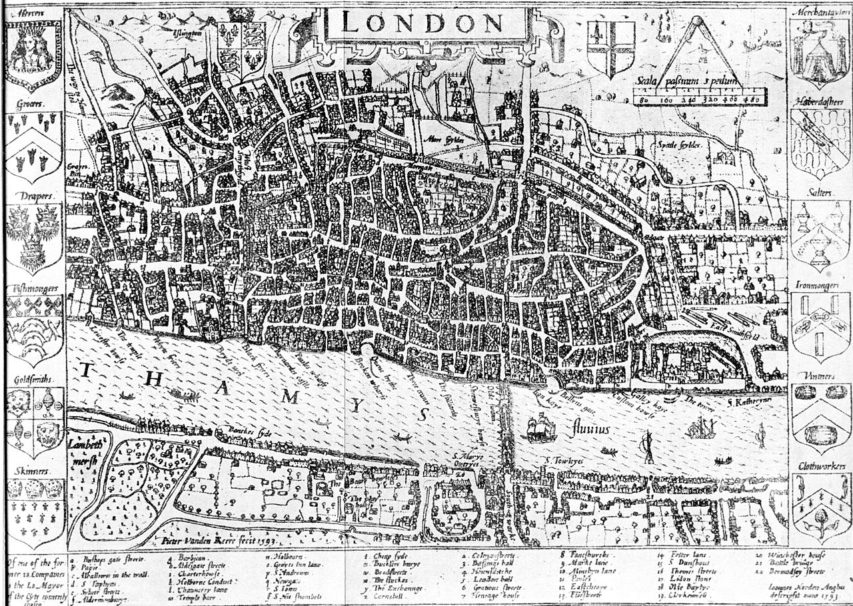

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

The other day, economic historian Tim Leunig tagged me into a comment on twitter with the line “intellectually I think the biggest change since settled agriculture was the idea that most people could live in cities and not produce food”. What’s interesting about that, I think, is the idea that this was not just an economic change, but an intellectual one. In fact, I’ve been increasingly noticing a sort of ideology, if one can call it that, which seemingly took hold in Britain in the late sixteenth century and then became increasingly influential. It was not the sort of ideology that manifested itself in elections, or even in factions, but it was certainly there. It had both vocal adherents and strenuous opponents, the adherents pushing particular policies and justifying them with reference to a common intellectual tradition. Indeed, I can think of many political and economic commentators who are its adherents today, whether or not they explicitly identify as such.

Today, the people who hold this ideology will occasionally refer to themselves as “urbanists”. They are in favour of large cities, large populations, and especially density. They believe strongly in what economists like to call “agglomeration effects” — that is, if you concentrate people more closely together, particularly in cities, then you are likely to see all sorts of benefits from their interactions. More ideas, more trade, more innovation, more growth.

Yet urbanism as a word doesn’t quite capture the full scope of the ideology. The group also heavily overlaps with natalists — people who think we should all have more babies, regardless of whether they happen to live in cities — and a whole host of other groups, from pro-immigration campaigners, to people setting up charter cities, to advocates of cheaper housing, to enthusiasts for mass transit infrastructure like buses, trams, or trains. The overall ideology is thus not just about cities per se — it seems a bit broader than that. Given the assumptions and aims that these groups hold in common, perhaps a more accurate label for their constellation of opinions and interests would be agglomerationism.

So much for today. What is the agglomerationist intellectual tradition? In the sixteenth century, one of the mantras that keeps cropping up is the idea that “the honour and strength of a prince consists in the multitude of the people” — a sentiment attributed to king Solomon. It’s a phrase that keeps cropping up in some shape or form throughout the centuries, and used to justify a whole host of agglomerationist policies. And most interestingly, it’s a phrase that begins cropping up when England was not at all urban, in the mid-sixteenth century — only about 3.5% of the English population lived in cities in 1550, far lower than the rates in the Netherlands, Italy, or Spain, each of which had urbanisation rates of over 10%. Even England’s largest city by far, London, was by European standards quite small. Both Paris and Naples were at least three times as populous (don’t even mention the vast sixteenth-century metropolises of China, or Constantinople).

Given their lack of population or density, English agglomerationists had a number of role models. One was the city of Nuremburg — through manufactures alone, it seemed, a great urban centre had emerged in a barren land. Another was France, which in the early seventeenth century seemed to draw in the riches to support itself through sheer exports. One English ambassador to France in 1609 noted that its “corn and grain alone robs all Spain of their silver and gold”, and warned that it was trying to create still new export industries like silk-making and tapestry weaving. (The English rapidly tried to do the same, though with less success.) France may not have been especially urban either, but Paris was already huge and on the rise, and the country’s massive overall population made it “the greatest united and entire force of any realm or dominion” in Christendom. Today, the population of France and Britain are about the same, but in 1600 France’s was about four times as large. Some 20 millions compared to a paltry 5. If Solomon was right, then England had a lot of catching up to do to even approach France in honour.

July 7, 2020

Taking stock after the worst of the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic

David Warren discusses an intractable “problem”:

I do not suppose it makes any practical difference what I have to say about a public health problem that invades the lives of billions; nor that readers will take me for a reliable epidemiologist when I say that the worst danger of that Batflu has now passed. (Infection rates spike, but the power of the virus to torture and kill has relented. The death rates continue downward.)

Nevertheless, I think there is some value in stating, even restating, the obvious — when what is obvious is in conflict with sensational reports, and the aggressive distortions of mass media, profiting from panic.

This Batflu became — more than any previous epidemic — a political issue, instantaneously. This is evident in the way it was spread, quite intentionally, by the Communist Party of China. (They shut down everything in Wuhan, except flights to Europe and America.) In all countries with democratic institutions, the disease became the centre of political attention, and unprecedented lockdowns were ordered. Likewise, unprecedented schemes of surveillance have significantly changed the relation between governments and governed, entirely for the worse. By means of current technology, the former will be able to perpetuate these changes, leaving those who wish to recover old liberties nowhere to hide.

Moreover, this is done by public demand. “The peeple” are easy to manipulate, once they have been frightened. The great majority of men, now and through the past, never cared about freedom. It has always been a minority concern, “for the intellectuals.” The “silent majority” will take their freedom, but only after their comfort and safety have been assured. The right to choose among consumer products is enough for them.

There are revolutions, such as the one that is now being attempted by the Left, but these never last. Either they are extinguished, under the wet blanket of public apathy, or the revolutionists succeed in installing a truly monstrous regime. Only thus, can they prolong their evil. Two generations of half-educated, indoctrinated, university grads favour a doctrinal dictatorship. Those still young are full of malign energy.

July 6, 2020

Cold War Two is upon us, but it’s not all Trump’s fault (believe it or not)

Niall Ferguson on the rapid drop in temperature in US/Chinese relations in the last eight years:

President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping at the G20 Japan Summit in Osaka, 29 June, 2019.

Cropped from an official White House photo by Shealah Craighead via Wikimedia Commons.

“We are in the foothills of a Cold War.” Those were the words of Henry Kissinger when I interviewed him at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Beijing last November.

The observation in itself was not wholly startling. It had seemed obvious to me since early last year that a new Cold War — between the U.S. and China — had begun. This insight wasn’t just based on interviews with elder statesmen. Counterintuitive as it may seem, I had picked up the idea from binge-reading Chinese science fiction.

First, the history. What had started out in early 2018 as a trade war over tariffs and intellectual property theft had by the end of the year metamorphosed into a technology war over the global dominance of the Chinese company Huawei Technologies Co. in 5G network telecommunications; an ideological confrontation in response to Beijing’s treatment of the Uighur minority in China’s Xinjiang region and the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong; and an escalation of old frictions over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Nevertheless, for Kissinger, of all people, to acknowledge that we were in the opening phase of Cold War II was remarkable.

Since his first secret visit to Beijing in 1971, Kissinger has been the master-builder of that policy of U.S.-Chinese engagement which, for 45 years, was a leitmotif of U.S. foreign policy. It fundamentally altered the balance of power at the mid-point of the Cold War, to the disadvantage of the Soviet Union. It created the geopolitical conditions for China’s industrial revolution, the biggest and fastest in history. And it led, after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, to that extraordinary financial symbiosis which Moritz Schularick and I christened “Chimerica” in 2007.

How did relations between Beijing and Washington sour so quickly that even Kissinger now speaks of Cold War?

The conventional answer to that question is that President Donald Trump has swung like a wrecking ball into the “liberal international order” and that Cold War II is only one of the adverse consequences of his “America First” strategy.

Yet that view attaches too much importance to the change in U.S. foreign policy since 2016, and not enough to the change in Chinese foreign policy that came four years earlier, when Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Future historians will discern that the decline and fall of Chimerica began in the wake of the global financial crisis, as a new Chinese leader drew the conclusion that there was no longer any need to hide the light of China’s ambition under the bushel that Deng Xiaoping had famously recommended.

June 30, 2020

QotD: Ideologies and belief systems

It’s really not a good thing because it manifests itself not only in individual psychopathologies, but also in social psychopathologies. That’s this proclivity of people to get tangled up in ideologies, and I really do think of them as crippled religions. That’s the right way to think about them. They’re like religion that’s missing an arm and a leg but can still hobble along. It provides a certain amount of security and group identity, but it’s warped and twisted and demented and bent, and it’s a parasite on something underlying that’s rich and true. That’s how it looks to me, anyways. I think it’s very important that we sort out this problem. I think that there isn’t anything more important that needs to be done than that. I’ve thought that for a long, long time, probably since the early ’80s when I started looking at the role that belief systems played in regulating psychological and social health. You can tell that they do that because of how upset people get if you challenge their belief systems. Why the hell do they care, exactly? What difference does it make if all of your ideological axioms are 100 percent correct?

People get unbelievable upset when you poke them in the axioms, so to speak, and it is not by any stretch of the imagination obvious why. There’s a fundamental truth that they’re standing on. It’s like they’re on a raft in the middle of the ocean. You’re starting to pull out the logs, and they’re afraid they’re going to fall in and drown. Drown in what? What are the logs protecting them from? Why are they so afraid to move beyond the confines of the ideological system? These are not obvious things. I’ve been trying to puzzle that out for a very long time. […]

Nietzsche’s idea was that human beings were going to have to create their own values. He understood that we had bodies and that we had motivations and emotions. He was a romantic thinker, in some sense, but way ahead of his time. He knew that our capacity to think wasn’t some free-floating soul but was embedded in our physiology, constrained by our emotions, shaped by our motivations, shaped by our body. He understood that. But he still believed that the only possible way out of the problem would be for human beings themselves to become something akin to God and to create their own values. He talked about the person who created their own values as the overman, or the superman. That was one part of the Nietzschean philosophy that the Nazis took out of context and used to fuel their superior man ideology. We know what happened with that. That didn’t seem to turn out very well, that’s for sure.

Jordan B. Peterson, “Biblical Series I: Introduction to the Idea of God” {transcript], jordanbpeterson.com, 2018-03-12.

June 26, 2020

Progressive hate for nuclear power

In Quillette, Michael Shellenberger discusses the demands of some climate activists who also reject the best solutions to the problems they foresee:

For the last decade I have been obsessed with a question: Why are the people who are the most alarmist about environmental issues also opposed to all of the obvious solutions?

Those who raise the alarm about food shortages oppose expanding the use of chemical fertilizers, tractors, and GMOs. Those who raise the alarm about Amazon deforestation promote policies that fragment the forest. And those who raise the alarm about climate change oppose nuclear energy, the largest source of zero-emissions energy in developed nations. Why is that?

It is not an academic question for me. I have been a climate activist for 20 years and an energy expert for 10 of them. I was adamantly against nuclear energy until about a decade ago when it became clear renewables couldn’t replace fossil fuels. After educating myself about the facts, I came to support the technology.

Over the last five years, I have campaigned, as founder and president of my small and independent nonprofit research organization, Environmental Progress, to expand the use of nuclear energy. During that time our main opponents have not been climate skeptics or even the fossil fuel industry but rather other climate activists.

This is the case around the world. It is climate alarmist Democrats and Greens who are seeking to shut down nuclear plants in the US and Europe. Greta Thunberg last year condemned the technology as “extremely dangerous, expensive, & time-consuming,” which is false. And Green New Deal architect Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) has advocated closing the Indian Point nuclear plant in New York, which is now being replaced with natural gas.

In nearly every situation around the world, support for nuclear energy from climate activists like Thunberg and AOC would make the difference between nuclear plants staying open or closing, and being built or not being built. Had Thunberg spoken out in defense of nuclear power she likely could have prevented two reactors in her home nation of Sweden from being closed. Had AOC advocated for Indian Point rather than condemned it as dangerous, it could likely keep operating, for at least 40 years longer.

That’s because the main problem facing nuclear energy is that it’s unpopular — and far more among progressives than conservatives, and far more among women than men. There are no good technical or economic reasons that nations from the US and Japan to Sweden and Germany are closing their nuclear plants. Center-left governments are closing them early in response to the demands of progressives and Greens — the very same people who are claiming climate change will kill billions of people.

Some prominent environmental groups have a pecuniary interest in replacing existing nuclear generating stations with natural gas and “renewable” energy sources, but money isn’t the only reason for the widespread opposition to nuclear power:

Sierra Club, NRDC, and EDF have worked to shut down nuclear plants and replace them with fossil fuels and a smattering of renewables since the 1970s. They have created detailed reports for policymakers, journalists, and the public purporting to show that neither nuclear plants nor fossil fuels are needed to meet electricity demand, thanks to energy efficiency and renewables. And yet, as we have seen, almost everywhere nuclear plants are closed, or not built, fossil fuels are burned instead.

But it’s not just about money. It’s also about ideology. Anti-nuclear groups have long had a deeply ideological motivation to kill off nuclear energy.

Policymakers, journalists, conservationists, and other educated elites in the ’50s and ’60s knew that nuclear was unlimited energy and that unlimited energy meant unlimited food and water.

We could use desalination to convert ocean water into freshwater. We could create fertilizer without fossil fuels, by harvesting nitrogen from the air, and hydrogen from water, and combining them. We could create transportation fuels without fossil fuels, by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to make artificial hydrocarbons, or by splitting water to make pure hydrogen gas.

Nuclear energy thus created a serious problem for Malthusians — followers of widely-debunked 18th-century economist, Thomas Robert Malthus — who argued that the world was on the brink of ecological collapse and resource scarcity. Nuclear energy not only meant infinite fertilizer, freshwater, and food but also zero pollution and a radically reduced environmental footprint.

In reaction, Malthusians attacked nuclear energy as dangerous, mostly by suggesting that it would lead to nuclear war, but also by spreading misinformation about nuclear “waste” — the tiny quantity of used fuel rods — and the rapidly decaying radiation that escapes from nuclear plants during their worst accidents.

There is a pattern: Malthusians raise the alarm about resource depletion or environmental problems and then attack the obvious technical solutions. In the late 1700s, Thomas Malthus had to reject birth control to predict overpopulation. In the 1960s, Malthusians had to claim fossil fuels were scarce to oppose the extension of fertilizers and industrial agriculture to poor nations and to raise the alarm over famine. And today, climate activists reject nuclear energy in order to declare a coming climate apocalypse.