TimeGhost History

Published 23 Mar 2025In 1947, the British divide the Raj into two nations, India and Pakistan, triggering one of the deadliest mass migrations in history. Sectarian violence between Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims leaves at least 200,000 dead and displaces millions more. Hastily drawn borders turn neighbours into enemies. The partition’s bloody legacy will lead to decades of tension, war, and bloodshed.

(more…)

March 29, 2025

Why India and Pakistan Hate Each Other – W2W 015 – 1947 Q3

March 27, 2025

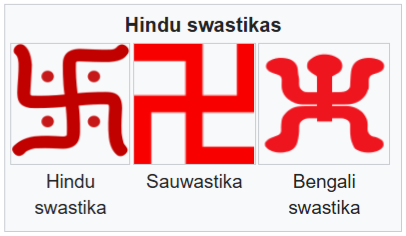

Ban the swastika? Are you some kind of racist?

In Ontario, the elected council for the Region of Durham has been reacting to a few painted swastika graffiti around the region over the last couple of months. To, as a politician might say, “send a message”, they proposed banning the use of the swastika altogether … failing to remember that it’s not just neo-Nazi wannabes who use it:

Durham council is adjusting the wording of its calls for a national ban on the Nazi swastika, or “Hakenkreuz“.

This follows efforts by religious advocates to distance their own symbols from the genocidal German fascist regime.

Swastikas often appear in Jain, Hindu and Buddhist iconography.

“The word ‘swastika’ means ‘well-being of all’,” explained Vijay Jain, president of Vishwa Jain Sangathan Canada, at Wednesday’s regional council meeting. “It’s a very sacred word. […] We use it extensively in our prayers.”

“Many Jain and Hindi parents give their children the name ‘Swastika’,” he added. “Many Hindi and Jain people, they keep their [business’s] name as ‘Swastika’. If you go to India, you’ll find the ‘Swastika’ name prominently used.”

“We stand in solidarity with the Jewish community and fully support all of the efforts by authorities to address growing antisemitism in Canada,” he said.

Regional council made its initial call for a ban on Nazi swastikas in February, after two separate incidents of the antisemitic symbol being scrawled inside a washroom at the downtown Whitby library.

On Wednesday, councillors voted to revise that motion to replace the word “swastika” with the term “Nazi symbols of hate”.

B’nai Brith Canada has been spearheading a petition campaign to have the Nazi symbol banned across the country.

The group has increasingly opted to refer to it by the alternative names “Nazi Hooked Cross” or “Hakenkreuz“.

On March 20, B’nai Brith put out a joint statement with Vishwa Jain Sangathan and other religious advocacy groups, calling for further differentiation between the symbols.

“These faiths’ sacred symbol (the Swastika) has been wrongfully associated with the Nazi Reich,” wrote Richard Robertson, B’nai Brith Canada’s Director of Research and Advocacy. “We must not allow the continued conflation of this symbol of peace with an icon of hate.”

December 11, 2024

Canada’s current situation, as viewed by Fortissax

Fortissax recently spoke to an audience in Toronto. This is part of the transcript of his speech:

No doubt, many of you already have an idea.

The fact of the matter is this: 25% of the people in this country are, or soon will be, foreigners. Most of them are not the children of immigrants but fresh-off-the-boat migrants.

The economy? It’s in the dumps. Canada has the lowest upward mobility in the OECD for young people. One of the lowest fertility rates in the Western world. And the fastest-changing demographics in the Western world — as I’m sure you’ve all noticed here in the streets of Toronto, the old capital of Anglo-Canadians.

Think about this: approximately 4.9 million foreigners are classified as “temporary migrants.” Combine that with permanent residents, refugees, and immigrants, and that number swells to 6.2 million in just four years.

And it doesn’t stop there.

Crime is reportedly the highest it’s ever been. We have no military. The Canadian Armed Forces has faced retention issues for two decades. And what is command preoccupied with? Men’s bathrooms stocked with tampons and servicemen being “radicalized” by wearing extremist clothing like MAGA hats.

Let’s not forget foreign influence.

The Chinese Communist Party exploited the Hong Kong handover in the 1990s to infiltrate Canada, using British Columbia as their foothold. As Sam Cooper exposes in Claws of the Panda and Willful Blindness, they established a stronghold in Metro Vancouver, taking over the business community.

This “Vancouver Model”, as we Canadians ironically call it, normalizes our capitulation to foreign hostiles. Triads, working hand-in-glove with the Chinese communists, built a global drug empire. Fentanyl, mass-produced in football field-sized factories in China, is shipped to Vancouver and distributed across the entire Western Hemisphere.

Let this sink in: more Canadians have died from this economic warfare than all our soldiers lost in the Second World War.

And now, there’s India.

Intelligence agencies from the Republic of India have demonstrated their ability to conduct assassinations on Canadian soil. Recently, a Khalistani nationalist and separatist was killed — a figure I’ll leave to your sympathies or judgments. Regardless, this marks a disturbing shift.

India weaponizes its diaspora against the international community. In exchange for non-alignment with China, the West — particularly the Anglosphere — uses Indian migrants as wage-slave labor to suppress costs.

The result? A disaster.

In Canada, Australia, the U.K., and increasingly the United States, we see Indians climbing the ladders of power, pursuing their own interests — often brazenly. In Brampton, part of Greater Toronto, a 50-foot statue of the Hindu god Hanuman looms.

And let’s not forget the Punjabi Sikh population. They openly support an independent Khalistan — or remain at best indifferent to the cause. They have infiltrated Canada’s state apparatus, even reaching the Ministry of National Defense, where Harjit Sajjan prioritized rescuing Afghan Sikhs during Kabul operations over broader Canadian interests.

In Surrey, British Columbia, the trucking industry is effectively controlled by Sikhs. In online spaces, Sikh nationalists demand Brampton be recognized as a province, seemingly aware that their homeland exists more abroad than in Punjab itself. The leader of the NDP, Jagmeet Singh, serves as yet another example — barred from entering India due to his sympathies for separatism.

But foreign influence is only half the story. Among our own lies another problem: disintegration.

Decades of Western alienation and economic parasitism by the federal government are fueling separatist movements in places like Alberta and Saskatchewan. In Quebec, the Parti Québécois is polling higher than the ruling CAQ, openly advocating for secession from Confederation.

Meanwhile, the federal Conservatives court immigrant voters, alienating native Canadians and abandoning their base.

And then there’s the economic misery.

The average Canadian home costs $700,000. The median income? Just $48,000. Upward mobility is nonexistent. The managerial regime hoards wealth and power, gatekeeping opportunity through credentialism, exorbitant tuition, and crushing taxes.

55% of Canadians have post-secondary education, and yet most have nothing to show for it. The regime is not run by titans of intelligence or visionaries. It’s run by ideologues — loyal to their cause, not to competence or merit.

The final insult: demographics.

Over the next six years, British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba will become majority non-Canadian. The 50% threshold will be breached, with profound consequences for local politics.

Ontario will hover just above 50%, while Quebec and the Maritime provinces will remain over 70% and 80% Canadian, respectively. This is not a death sentence, but it is a profound transformation for Western Canada, which has historically been more propositional and less identitarian than the East.

This is where we are.

Our sovereignty is compromised. Our identity is eroded. But we are not yet defeated. What happens next depends entirely on us.

April 30, 2024

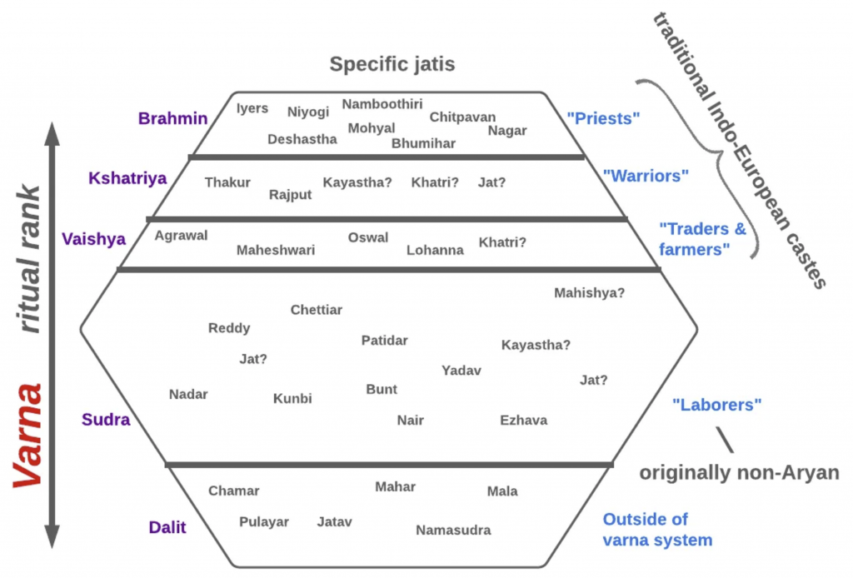

DNA and India’s caste system

Earlier this month, Palladium published Razib Khan‘s look at the genetic components of India’s Caste System:

Though the caste system dominates much of Indian life, it does not dominate Indian American life. At slightly over 1% of the U.S. population, only about half of Indian Americans identify as Hindu, the religion from which the broader categories of caste, or varna, emerge. While caste endogamy — marrying within one’s caste — in India remains in the range of 90%, in the U.S. only 65% of American-born Indians even marry other people of subcontinental heritage, and of these, a quick inspection of The New York Times weddings pages shows that inter-caste marriages are the norm. While tensions between the upper-caste minority and middle and lower castes dominate Indian social and political life, 85% of Indian Americans are upper-caste, broadly defined, and only about 1% are truly lower-caste. Ultimately, the minor moral panic over caste discrimination among a small minority of Americans is more a function of our nation’s current neuroses than the reality of caste in the United States.

But this does not mean that caste is not an important phenomenon to understand. In various ways, caste impacts the lives of the more than 1.4 billion citizens of India — 18% of humans alive today — whatever their religion. While the American system of racial slavery is four centuries old at most, India’s caste system was recorded by the Greek diplomat Megasthenes in 300 BC, and is likely far more ancient, perhaps as old as the Indus Valley Civilization more than 4,000 years ago. Indian caste has a deep pedigree as a social technology, and it illustrates the outer boundary of our species’ ability to organize itself into interconnected but discrete subcultures. And unlike many social institutions, caste is imprinted in the very genes of Indians today.

Of Memes and Genes

Beginning about twenty-five years ago, geneticists finally began to look at the variation within the Indian subcontinent, and were shocked by what they found. In small villages in India, Dalits, formerly called “outcastes,” were as genetically distinct from their Brahmin neighbors as Swedes were from Sicilians. In fact, a Brahmin from the far southern state of Tamil Nadu was genetically closer to a Brahmin from the northern state of Punjab then they were to their fellow non-Brahmin Tamils. Dalits from the north were similar to Dalits from the south, while the three upper castes, Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, tended to cluster together against the Sudras.

Some scholars, like Nicholas Dirks, the former chancellor of UC Berkeley, argued for the mobility and dynamism of the caste system in their scholarship. But the genetic evidence seemed to indicate a level of social stratification that echoes through millennia. Across the subcontinent, Dalit castes engaged in menial and unsanitary labor and therefore were considered ritually impure. Meanwhile, Brahmins were the custodians of the Hindu Vedic tradition that ultimately bound the Indic cultures together with other Indo-European traditions, like that of the ancient Iranians or Greeks. Other castes also had their occupations: Kshatriyas were the warriors, while Vaishyas were merchants and other economically productive occupations.

Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas were traditionally the three “twice-born” castes, allowing them to study the Hindu scriptures after an initiatory ritual. The majority of the population were Sudras (or Shudras), India’s peasant and laboring majority. Shudras could not study the scriptures, and might be excluded from some temples and festivals, but they were integrated into the Hindu fold, and served by Brahmin priests. A traditional ethnohistory posits that elite Brahmin priests and Kshatriya rulers combined with Vaishya commoners formed the core of the early Aryan society in the subcontinent, with Shudras integrated into their tribes as indigenous subalterns. Outcastes were tribes and other assorted latecomers who were assimilated at the very bottom of the social system, performing the most degrading and impure tasks.

The caste system as a layered varna system with five classes and numerous integrated jati communities.

Razib KhanThis was the theory. Reality is always more complex. In India, the caste system combines two different social categories: varna and jati. Varna derives from the tripartite Indo-European system, in India represented by Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas. It literally translates as “color”, white for Brahmin purity, red for Kshatriya power, and yellow for Vaishya fertility. But India also has Shudras, black for labor. In contrast to the simplicity of varna, with its four classes, jati is fractured into thousands of localized communities. If varna is connected to the deep history of Indo-Aryans and is freighted with religious significance, jati is the concrete expression of Indian communitarianism in local places and times.

January 19, 2024

January 13, 2024

QotD: Brahmins and Mandarins

Traditional Hindu society knew hundreds of hereditary castes and subcastes, but all broadly fit into four major “varna” (“colors”, strata):

- Brahmins (scholars, clerisy)

- Kshatriya (warriors, rulers)

- Vaishya (traders, skilled artisans)

- Shudras (farmers)

- The un-counted fifth varna are the Dalit (“untouchables”, outcasts in both senses of the word)

Historical edge cases aside, membership in the Brahmin stratum was hereditary, even more so than in the nobility of feudal Europe. At least there, kings might raise a commoner to a knighthood or even the peerage for merit or political expedience: one need not wait for reincarnation into a higher caste.

The Sui dynasty in China, however, took a different route. Seeking both to curb the power of the hereditary nobles and to broaden the available talent pool for administrators, they instituted a system of civil service examinations. With interruptions (e.g. under the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan) and modifications, that system remained in place for thirteen centuries until finally abolished in 1904. Westerners refer to laureates of the Imperial Examinations (from the entry-level shengyuan to the top-level jinshi) by the collective term Mandarins. Ironically, this term comes not from any Chinese dialect but (via Malay and Portuguese) from the Sanskrit word mantri (counselor, minister) — cf. the Latin mandatum (command) and its English cognate “mandate”.

Initially, the exams were limited to the scholar and yeoman farmer classes: with time, they were at least in theory opened up to all commoners in the “four occupations” (scholars, farmers, artisans, merchants), with jianmin (those in “base occupations”) still excluded. The process also was ostensibly fair: exams were written, administered at purpose-built examination halls with individual three-walled examination cubicles to eliminate cribbing. Moreover, exam copies were identified by number rather than by name. […]

In practice, the years of study and the costs of hiring tutors for the exam limited this career path to the wealthy. Furthermore, the success rate was very low (between 0.03% and 1%, depending on the source) so one had better have a fallback trade or independent wealth. In some cases, rich families who for some reason were barred from the exams would sponsor a bright student from a poor family. Once the student became a government official, he would owe favors to the sponsor.

Moreover, the subject matter of the exam soon became ossified and tested more for conformity of thought, and ability to memorize text and compose poetry in approved forms, than for any skill actually relevant to practical governance. (Hmm, artists or scholars in a narrow abstruse discipline being touted as authorities on economic or foreign policy: verily, there is nothing new under the sun.)

Nitay Arbel, “Brahmandarins”, According to Hoyt, 2019-10-08.

February 1, 2023

Changing views of Gandhi

In UnHerd, Pratinav Anil recounts some of the changes to Gandhi’s reputation and place in Indian public memory:

Gandhi, poor fellow, had his ashes stolen on the 150th anniversary of his birth. “Traitor”, scrawled the Hindu supremacist malcontents on a life-size cut-out of the Mahatma at the mausoleum. That was a couple of years ago, but it’s a sentiment that’s grown shriller since. Unsurprisingly. In government as in schools, in newsrooms as on social media, the founding father’s defenders are being put out of business by his detractors. His Congress Party, after 50 years of near-uninterrupted rule since independence in 1947, is now in ruins, upstaged by the Bharatiya Janata Party. Hindu supremacists have stolen the show, while India’s Muslims, Christians, and Dalits are persecuted. With the changing of the guard, Gandhi’s extravagant ideal — unity in diversity — has gone the way of his ashes.

His reputation, too, is in tatters. Last year, the National Theatre staged a play about his assassination. But The Father and the Assassin centred not on Gandhi but Godse, the man who killed him 75 years ago this week. Here is a tender portrait of a tortured soul, a blushing boy raised as a girl to propitiate the gods who had taken away his three brothers, who becomes radicalised and blames Gandhi for betraying Hindus and mollycoddling Muslims, so causing Partition. It is no accident that Godse was a card-carrying Hindu supremacist, a member of the parent organisation of the BJP, to which India’s new ruler Narendra Modi belongs. Today, statues of Godse are going up across the country just as statues of Gandhi are being pulled down across the world.

Needless to say, this is a most disturbing development. Yet the reaction of liberals, Indian as well as Western, has been no less troubling. An unthinking anti-imperialism of old has joined up with an unthinking anti-Hindu supremacism of new to beget a bastardised Gandhi. What we have is not a creature of flesh and blood, possibly a great if also flawed man, but rather a deified hero. This is the Gandhi with a saintly halo around him who greets you from Indian billboards, grins at you from rupee notes, stares down at you from his plinth on Westminster’s Parliament Square, and, in Ben Kingsley’s portrayal of him, slathered in a thick impasto of fake tan, moves you to a standing ovation.

This is the easily comestible fortune-cookie Gandhi you encounter in airport bestsellers such as Ramachandra Guha’s double-decker hagiography, and also the sartorial icon whose wire-rim glasses were emulated by Steve Jobs. There is the Gandhi of the gags, most famous for a retort he probably never made: asked what he thought of Western civilisation, the Mahatma is reported to have replied: “I think it would be a good idea.” Ba-dum ching! Then there’s the Christological Gandhi, a modern messiah turning the other cheek: “An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.” There’s also Gandhi the self-help guru: “Be the change that you wish to see in the world.” One could go on.

Here’s where the historian in me says, would that it were so simple. Gandhi was no liberal. And if those who sing his praises today knew a little more about Gandhi the man, rather than Gandhi the saint, their adulation would very quickly dry up. The fact is that the Mahatma hasn’t aged well. He detested democracy, defended the caste system, and had a deeply disturbing relationship with sex.

None of this should surprise us. Unlike some of the more cerebral thinkers of his cohort, figures such as Ambedkar and Periyar, Gandhi possessed a shallow mind. The product of a rather parochial education, admittedly the best that could be bought in turn-of-the-century western India, he struggled to juggle academic and conjugal demands. His precocious marriage to Kasturbai at 13 was a misalliance, perennially troubled by his suspicions of her infidelity. Not the sharpest knife in the drawer, he dropped out of Samaldas College. It was only in London, where he went to read law, that his horizons widened.

Then again, not for the better.

October 30, 2022

July 3, 2021

Who were the Mughals? Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire explained

Epimetheus

Published 20 Oct 2019Who were the Mughals? Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire explained (Documentary)

The Mughal empire’s history from Babur to the fall in 1857.

This video and others like it are sponsored by my Patrons over on patreon.

https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776

June 28, 2021

QotD: Urbanization

The environmentalist aesthetic is to love villages and despise cities. My mind got changed on the subject a few years ago by an Indian acquaintance who told me that in Indian villages the women obeyed their husbands and family elders, pounded grain, and sang. But, the acquaintance explained, when Indian women immigrated to cities, they got jobs, started businesses, and demanded their children be educated. They became more independent, as they became less fundamentalist in their religious beliefs. Urbanization is the most massive and sudden shift of humanity in its history.

Stewart Brand, “Environmental Heresies”, Technology Review, 2005-05

June 1, 2021

Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire explained in less than 7 minutes

Epimetheus

Published 8 Oct 2019Rise and Fall of the Sikh Empire explained in less than 7 minutes Sikh history documentary

This video covers Sikh history from the Guru Nanak till the fall of the Sikh Empire.

This video and others like it are sponsored by my Patrons over on patreon.

https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776

January 25, 2021

QotD: Indira Gandhi’s exploitation of the goddess Kali

In colonial India, Kali’s notoriety boomed. For in her both coloniser and colonised found a figurehead. Corrupted by the British, Kali was spun as a sexually depraved, blood-swigging black sorceress. As William Ward phrased it in his encyclopaedia, “She exhibits altogether the appearance of a drunken frantic fury … on whose altar victims annually bleed”. Such descriptions, deemed by Indians to be reductively fixated on her destructive powers to the omission of her maternal reserve, activated a movement for her reclamation and turned her into an icon in the struggle for Indian independence in the late-nineteenth century. Put on calendars, cigarette packets, matchboxes, and subject of hugely popular prints, Kali was embraced as a vision of freedom. The reverence for her was inseparable from politics. And it took just two decades after India gained its freedom for a politician to exploit it.

Indira Gandhi — the daughter of one of the freedom movement’s protagonists Pandit Nehru and India’s first and only female prime minister — chose consciously to co-opt this divinity in service of burnishing her own self-image. Indeed, during her first spell in office, from 1966-1977, Indira’s image was as prolific as the colourful printed pictures of the tantric goddess splashed across India’s towns and bazaars. Her appearance was, understandably, more benign. But in India’s jostling visual marketplace her image — big smile and bobbed black hair shot with a streak of white framed by a demure uttariya (veil) — was as inescapable as any deity’s.

Indira played the demagogue superbly. But just as her popularity among Indians soared, and her political confidence grew, those around her began equating her strong, intolerant, and cold politics with female divinities and their overwhelming powers. According to a hugely contentious apocryphal story, Indira’s young rival Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who would go on to succeed her as prime minister, was so overcome by devotion at the sight of her gallantry during India’s war with Pakistan in 1971 that he called her Ma Durga — Kali’s mother.

Cleo Roberts, “Indira Gandhi: a gift from the gods?”, The Critic, 2020-10-15.

August 17, 2020

Dateline Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, 5 August 2020

That’s a significant date, as Tom Holland explains at UnHerd:

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi performing Bhoomi Pujan at Shree Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir, in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh on August 05, 2020.

Photo released by the Press Information Bureau on behalf of the Prime Minister’s Office, (ID 90071) via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week, on 5 August, the Prime Minister of India laid a foundation stone and helped bury a distinctive period in global history. Narendra Modi had travelled to Ayodhya, a city long identified by Hindus with one of their most beloved gods. Lord Rama — avatar of Vishnu and hero of the Sanskrit epic, the Ramayana — was said to have ruled within its walls as the very model of those who uphold truth and justice. Like Camelot, the court of Rama glimmers tantalisingly in the imaginings of those who fall beneath its spell: the reminder of a vanished golden age, the hope that it might come again.

In recent decades, the mingled regret and yearning that the memory of Rama’s capital can inspire among Hindus had come to be focused on one particular location in the modern city of Ayodhya: the Ram Janmabhoomi, the “birthplace of Rama”. At the moment, nothing serves to mark the sacred spot. But soon enough that will change. A great complex of buildings will rise. As Modi, officially declaring the process of construction begun, put it: “A great temple will now be built for our Lord Rama.”

A fortnight earlier, the President of Turkey had celebrated a similar reconsecration. In 1453, when the Christian capital of Constantinople fell to the Ottomans, its most stupefying building, the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia, had been converted into a mosque, and duly served for almost half a millennium as a monument to the triumph of Islam over a defeated and superceded order. Then, in 1935, a decade and more after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and its replacement within its heartlands by a Turkish republic, the mosque of Ayasofya was turned into a museum. So, for decades, it remained. Then, this summer, the museum once again became a mosque. On 24 July, Hagia Sophia opened for Friday prayers. “It is breaking away from its chains of captivity,” President Erdogan declared rhapsodically. “It was the greatest dream of our youth. It was the yearning of our people and it has been accomplished.”

The synchronicity between Modi’s trip to Ayodhya and Erdogan’s to Hagia Sophia is striking, and only flimsily obscured by the fact that the Prime Minister of India is trampling the legacy of an Islamic empire much as the President of Turkey has trampled the legacy of a Christian one. In the early sixteenth century, shortly after the Moghul conquest of the lands that once, so Hindus believed, had constituted the Ram Rajya, the “realm of Rama”, a mosque was built in Ayodhya. By the twentieth century, large numbers of Hindus had come to believe that this same mosque, the Babri Masjid, stood directly on the site of the Ram Janmabhoomi. In the 1980s, the BJP — the party to which Modi belongs — began a campaign to demolish it. In 1992 a mob duly tore it down. Communal riots exploded. Thousands died.

Last November, even as the site was formally granted to Hindus, the Supreme Court of India condemned the demolition of the mosque as a crime. But a crime by whose standards? Not, it would seem, by Modi’s. Just as Erdogan justified the conversion of Hagia Sophia to a mosque by “right of conquest”, so the Prime Minister of India, hailing the opportunity to build a temple on the site where the Babri Masjid had stood, invoked the ancient traditions of his country. It was, he declared, “a unique gift from law-abiding India to truth, non-violence, faith and sacrifice.” History as well as justice stood on his side.

August 10, 2020

QotD: Gandhi’s legacy

Some Indians feel that after the early 1930s, Gandhi, although by now world-famous, was in fact in sharp decline. Did he at least “get the British out of India”? Some say no. India, in the last days of the British Raj, was already largely governed by Indians (a fact one would never suspect from this movie), and it is a common view that without this irrational, wildly erratic holy man the transition to full independence might have gone both more smoothly and more swiftly. There is much evidence that in his last years Gandhi was in a kind of spiritual retreat and, with all his endless praying and fasting, was no longer pursuing (the very words seem strange in a Hindu context) “the public good.” What he was pursuing, in a strict reversion to Hindu tradition, was his personal holiness. In earlier days he had scoffed at the title accorded him, Mahatma (literally “great soul”). But toward the end, during the hideous paroxysms that accompanied independence, with some of the most unspeakable massacres taking place in Calcutta, he declared, “And if … the whole of Calcutta swims in blood, it will not dismay me. For it will be a willing offering of innocent blood.” And in his last days, after there had already been one attempt on his life, he was heard to say, “I am a true Mahatma.”

We can only wonder, furthermore, at a public figure who lectures half his life about the necessity of abolishing modern industry and returning India to its ancient primitiveness, and then picks a Fabian socialist, already drawing up Five-Year Plans, as the country’s first Prime Minister. Audacious as it may seem to contest the views of such heavy thinkers as Margaret Bourke-White, Ralph Nader, and J.K. Galbraith (who found the film’s Gandhi “true to the original” and endorsed the movie wholeheartedly), we have a right to reservations about such a figure as a public man.

I should not be surprised if Gandhi’s greatest real humanitarian achievement was an improvement in the treatment of Untouchables — an area where his efforts were not only assiduous, but actually bore fruit. In this, of course, he ranks well behind the British, who abolished suttee — over ferocious Hindu opposition — in 1829. The ritual immolation by fire of widows on their husbands’ funeral pyres, suttee had the full sanction of the Hindu religion, although it might perhaps be wrong to overrate its importance. Scholars remind us that it was never universal, only “usual.” And there was, after all, a rather extensive range of choice. In southern India the widow was flung into her husband’s fire-pit. In the valley of the Ganges she was placed on the pyre when it was already aflame. In western India, she supported the head of the corpse with her right hand, while, torch in her left, she was allowed the honor of setting the whole thing on fire herself. In the north, where perhaps women were more impious, the widow’s body was constrained on the burning pyre by long poles pressed down by her relatives, just in case, screaming in terror and choking and burning to death, she might forget her dharma. So, yes, ladies, members of the National Council of Churches, believers in the one God, mourners for that holy India before it was despoiled by those brutish British, remember suttee, that interesting, exotic practice in which Hindus, over the centuries, burned to death countless millions of helpless women in a spirit of pious devotion, crying for all I know, Hai Rama! Hai Rama!

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

July 17, 2020

QotD: Gandhi’s views on chastity

… even more important, because it is dealt with in the movie directly — if of course dishonestly — is Gandhi’s parallel obsession with brahmacharya, or sexual chastity. There is a scene late in the film in which Margaret Bourke-White (again!) asks Gandhi’s wife if he has ever broken his vow of chastity, taken, at that time, about forty years before. Gandhi’s wife, by now a sweet old lady, answers wistfully, with a pathetic little note of hope, “Not yet.” What lies behind this adorable scene is the following: Gandhi held as one of his most profound beliefs (a fundamental doctrine of Hindu medicine) that a man, as a matter of the utmost importance, must conserve his bindu, or seminal fluid. Koestler (in The Lotus and the Robot) gives a succinct account of this belief, widespread among orthodox Hindus: “A man’s vital energy is concentrated in his seminal fluid, and this is stored in a cavity in the skull. It is the most precious substance in the body … an elixir of life both in the physical and mystical sense, distilled from the blood … A large store of bindu of pure quality guarantees health, longevity, and supernatural powers … Conversely, every loss of it is a physical and spiritual impoverishment.” Gandhi himself said in so many words, “A man who is unchaste loses stamina, becomes emasculated and cowardly, while in the chaste man secretions [semen] are sublimated into a vital force pervading his whole being.” And again, still Gandhi: “Ability to retain and assimilate the vital liquid is a matter of long training. When properly conserved it is transmuted into matchless energy and strength.” Most male Hindus go ahead and have sexual relations anyway, of course, but the belief in the value of bindu leaves the whole culture in what many observers have called a permanent state of “semen anxiety.” When Gandhi once had a nocturnal emission he almost had a nervous breakdown.

Gandhi was a truly fanatical opponent of sex for pleasure, and worked it out carefully that a married couple should be allowed to have sex three or four times in a lifetime, merely to have children, and favored embodying this restriction in the law of the land. The sexual-gratification wing of the present-day feminist movement would find little to attract them in Gandhi’s doctrine, since in all his seventy-nine years it never crossed his mind once that there could be anything enjoyable in sex for women, and he was constantly enjoining Indian women to deny themselves to men, to refuse to let their husbands “abuse” them. Gandhi had been married at thirteen, and when he took his vow of chastity, after twenty-four years of sexual activity, he ordered his two oldest sons, both young men, to be totally chaste as well.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.