In The Line, Phil A. McBride explains how the “net giants” have steadily nibbled away at the built-in resilience of the original internet design so that we’re all far more vulnerable to network outages than ever before:

The Internet was originally conceived in the 1960s to be a resilient, disparate and distributed network that didn’t have any single point of failure. This is still true today. While there are large data centres around the world that aggregate traffic, we don’t depend on them. If one were to go offline, things would slow down, but the data would still flow.

The advent of the cloud, though, has completely changed how we use the Internet, especially in the worlds of business, education and government. And the cloud, alas, is not nearly as resilient.

Fifteen years ago, your average small or medium business would have their own servers. Those servers would be used to send/receive email, store files, and run various business or collaborative applications. Some of these servers may have been hosted offsite at a data centre to provide better security or speed of access, but the physical infrastructure belonged to someone — it was something you could touch and, more importantly, account for. Many companies kept their servers on site.

If a company’s server or network went down, it affected that company. They couldn’t send or receive email, they couldn’t open files, collaborate with staff or clients. They were offline.

But only they were offline.

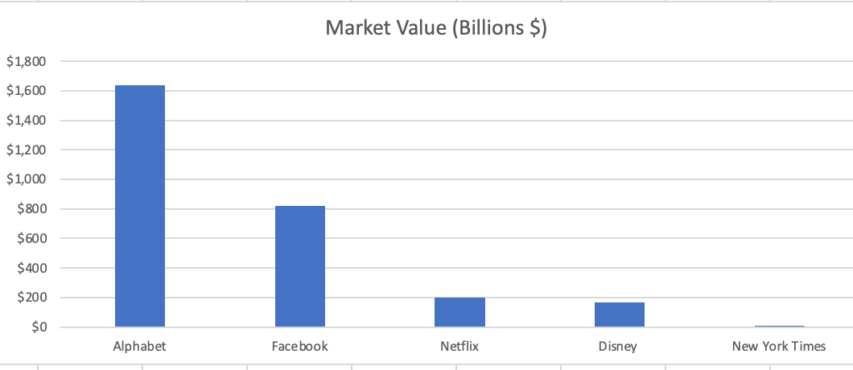

Fast forward to today. Microsoft 365 dominates the corporate productivity services market with an estimated 45-50 per cent market share worldwide, with Google Workspace coming second, with around 30-35 per cent. This means that approximately 80 per cent of businesses are dependent on one of two vendors for their ability to transact business and communicate at even the most basic level.

Government and government-provided services, like education, health care and defence, are just as reliant on these services as the business world.

In today’s world, when Microsoft’s or Google’s services suffer a hiccup, it doesn’t affect one business. Or ten, or a hundred. Tens of thousands of business, and government offices and civil society institutions, all go offline. Simultaneously. Mom-and-pop stores, multi-billion-dollar corporations, elementary schools, hospitals, entire governments, all go out, all at once.

And we haven’t even talked about how Amazon, Microsoft and Google control almost two-thirds of the world’s web/application hosting market share. If one or all of those services go down, most of the websites you go to on a regular basis would suddenly become unreachable.

Kinda-sorta related to the above is Ted Gioia‘s “State of the Culture” post:

So remember the first rule: The culture always changes first. And then everything else adapts to it.

That’s why teens plugged into the most lowbrow culture often grasp the new reality long before elites figure it out. This was true 50 years ago, and it’s still true today.

So that’s our second rule: If you want to understand the emerging culture, look at the lives of teens and twenty-somethings — and especially their digital lives. (In some cases those are their only lives.)

The web has changed a lot in recent years, hasn’t it? Not long ago, the Internet was loose and relaxed. It was free and easy. It was fun. There wasn’t even an app store.

We made our own rules.

The web had removed all obstacles and boundaries. I could reach out to people all over the world.

The Internet, in those primitive days, put me back in touch with classmates from my youth. It reconnected me with friends I’d made during my many trips overseas. It strengthened my ties with relatives near and far. I even made new friends online.

It felt liberating. It felt empowering.

But it also helped my professional life. I had regular exchanges with writers and musicians in various cities and countries—without leaving the comfort of my home.

I made new connections. I opened new doors.

And this didn’t just happen to me. It happened to everybody.

“The world is flat,” declared journalist Thomas Friedman. All the barriers were gone — we were all operating on the same level. It felt like some imaginary Berlin Wall had fallen.

That culture of flatness changed everything. Ideas spread faster. Commerce moved more easily. Every day I encountered something new from some place far away.

But then it changed.

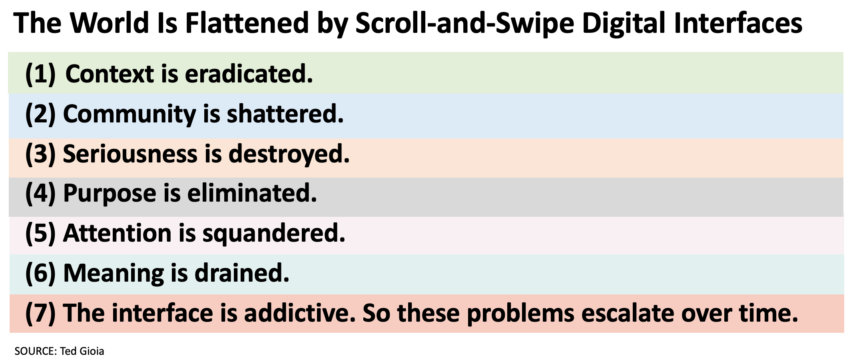

Twenty years ago, the culture was flat. Today it’s flattened.

I still participate in many web platforms — I need to do it for my vocation. (But do I really? I’ve started to wonder.) But now they feel constraining.

Even worse, they now all feel the same.

Instead of connecting with people all over the world, I now get “streaming content” 24/7.

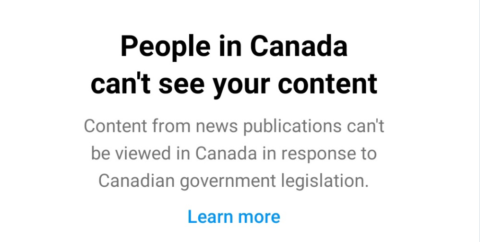

Facebook no longer wants me stay in touch with friends overseas, or former classmates, or distant relatives. Instead it serves up memes and stupid short videos.

And they are the exact same memes and videos playing non-stop on TikTok — and Instagram, Twitter, Threads, Bluesky, YouTube shorts, etc.

Every big web platforms feels the exact same.

That whole rich tapestry of my friends and family and colleagues has been replaced by the most shallow and flattened digital fluff. And this feeling of flattening is intensified by the lack of context or community.

The only ruling principle is the total absence of purpose or seriousness.

The platforms aggravate this problem further by making it difficult to leave. Links are censored. Intelligence is punished by the dictatorship of the algorithms. Every exit is blocked, and all paths lead to the endless scroll.

All this should be illegal. But somehow it isn’t.