It is probable that the nature of modern war has made “democratic army” a contradiction in terms. The French army, for instance, based on universal service, is hardly more democratic than the British. It is just as much dominated by the professional officer and the long-service N.C.O., and the French officer is probably rather more “Prussian” in outlook than his British equivalent. The Spanish Government militias during the first six months of war — the first year, in Catalonia — were a genuinely democratic army, but they were also a very primitive type of army, capable only of defensive actions. In that particular case a defensive strategy, coupled with propaganda, would probably have had a better chance of victory than the methods casually adopted. But if you want military efficiency in the ordinary sense, there is no escaping from the professional soldier, and so long as the professional soldier is in control he will see to it that the army is not democratised. And what is true within the armed forces is true of the nation as a whole; every increase in the strength of the military machine means more power for the forces of reaction. It is possible that some of our more Left-wing jingoes are acting with their eyes open. If they are, they must be aware that the News-Chronicle version of “defence of democracy” leads directly away from democracy, even in the narrow nineteenth-century sense of political liberty, independence of the trade unions and freedom of speech and the press.

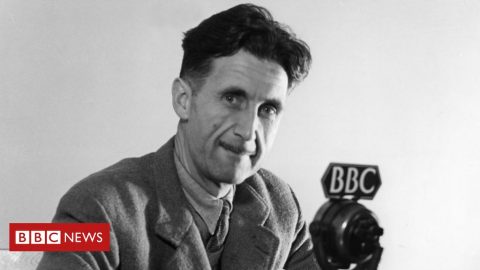

George Orwell, “Democracy in the British Army”, Left, 1939-09.

December 7, 2019

QotD: A “democratic” army

November 13, 2019

November 9, 2019

QotD: British Cookery

When Voltaire made his often-quoted statement that the country of Britain has “a hundred religions and only one sauce”, he was saying something which was untrue and which is equally untrue today, but which might still be echoed in good faith by a foreign visitor who made only a brief stay and drew his impressions from hotels and restaurants. For the first thing to be noticed about British cookery is that it is best studied in private houses, and more particularly in the homes of the middle-class and working-class masses who have not become Europeanised in their tastes. Cheap restaurants in Britain are almost invariably bad, while in expensive restaurants the cookery is almost always French, or imitation French. In the kind of food eaten, and even in the hours at which meals are taken and the names by which they are called, there is a definite cultural division between the upper-class minority and the big mass who have preserved the habits of their ancestors.

Generalising further, one may say that the characteristic British diet is a simple, rather heavy, perhaps slightly barbarous diet, drawing much of its virtue from the excellence of the local materials, and with its main emphasis on sugar and animal fats. It is the diet of a wet northern country where butter is plentiful and vegetable oils are scarce, where hot drinks are acceptable at most hours of the day, and where all the spices and some of the stronger-tasting herbs are exotic products. Garlic, for instance, is unknown in British cookery proper: on the other hand mint, which is completely neglected in some European countries, figures largely. In general, British people prefer sweet things to spicy things, and they combine sugar with meat in a way that is seldom seen elsewhere.

Finally, it must be remembered that in talking about “British cookery” one is referring to the characteristic native diet of the British Isles and not necessarily to the food that the average British citizen eats at this moment. Quite apart from the economic difference between the various blocks of the population, there is the stringent food rationing which has now been in operation for six years. In talking of British cookery, therefore, one is talking of the past or the future – of dishes that the British people now see somewhat rarely, but which they would gladly eat if they had the chance, and which they did eat fairly frequently up to 1939.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

November 7, 2019

Replacing “dead, white male” writers with contemporary First Nations writers

Barbara Kay, as you would expect is not a fan of this move by this school board in the Windsor area:

Some years ago, the late, great writer George Jonas asked me about my intellectual influences. Who did I remember as especially formative? Oh, George Orwell, of course. I read Animal Farm in my mid-teens, 1984 a little later, and most of his other writings over the course of my salad years. It would be hard to overstate his effect on my understanding of concepts like “freedom,” “power” and “decency.”

Since Orwell has never been “owned” by the right or the left, both admiring his prose as a model for clarity and coherence, he is the one English-language writer I would consider indispensable for any high school literature curriculum.

Up to now, most educators have concurred. But the Windsor, Ont.-area Greater Essex County District School Board has announced that, in accordance with the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Orwell and other canon favourites in the Grade 11 literature curriculum, including Shakespeare, will be set aside in favour of a course wholly devoted to Indigenous writing. Eight of the district’s 15 schools have already replaced former standards with such books as Indian Horse, In This Together and Seven Fallen Feathers under the rubric of Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis and Inuit Voices.

“This decision wasn’t made lightly,” said Tina DeCastro, a teacher consultant with the school board’s Indigenous Education Team. The decision arose from a motion passed by the school board’s trustees as a response to TRC calls for action. Eastern Cherokee Sandra Muse Isaacs, Professor of Indigenous Literature at the University of Windsor, defends the radical change as necessary on the grounds that Indigenous stories have been ignored in the past. “Our stories predate Canada. It’s as simple as that.”

Is it really that simple?

I don’t think there is a sentient Canadian today who isn’t aware that Indigenous voices have been neglected in the past, and who would not wholeheartedly support the addition of Indigenous writing to contemporary literature curricula. But an entire year devoted to Indigenous literature that supplants revered works by great writers from the civilization that produced Canada as a nation-state, in order to redress the offence of historical inattention to Indigenous people, is to rob the majority of Canadian students of their cultural patrimony.

November 6, 2019

QotD: “Fake news” is nothing new

… the basic ideas of “alternative facts” and “fake news” — our updated, revved-up forms of disinformation — were not foreign to Orwell. Working at the BBC as a news producer — a fancy term for war propagandist — he heard some of the Axis powers’ propaganda as well as that of his own side (even if he kept his own hands fairly clean). He justifiably feared that the very concept of objective truth was fading from the modern world. Winston Smith’s job at the Ministry of Truth is to rewrite or “rectify” history, so that it follows the current party line, whatever it may be at that moment.

Orwell himself saw all this happen when he read Catalan newspapers as well as British ones during the Spanish Civil War, several years before joining the BBC. Condemning press distortions, above all how several English newspapers reported the war, he wrote: “I saw great battles where there had been no fighting and complete silence where hundreds of men had been killed … I saw, in fact, history being written not in terms of what happened but what ought to have happened according to various ‘party lines.'” Given the gridlock in American politics, and the never-ending verbal warfare between news outlets on the Right such as Fox News and on the Left such as MSNBC, Orwell appears all too accurate in his “predictions.”

One of the features of the world of Oceania reflecting Orwell’s prescience is its official language, Newspeak, an argot resembling a kind of Morse code that satirizes advertising norms, political jargon, and government bureaucratese. The purpose of Newspeak is to limit thought, on the view that “you can’t think what you lack the words for.” Ultimately, this impoverished language seeks to narrow and control human thought. (Does Twitter represent a step in that direction?) Purged of all nuance and subtlety, denuded of variety, and reduced to a few hundred simple words, Newspeak ultimately promises to render all independent thought (or “thoughtcrime”) impossible. If it cannot be expressed in language, it cannot be thought. And anything can fill the vacuum, such as 2 + 2 = 5. That is the equation — a perfect example of “doublethink” — which O’Brien indoctrinates Winston to accept in Room 101 and which marks the final step of the latter’s brainwashing. As the Party defines it, “doublethink” consists in holding “two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.” In 2018, Trump’s lead lawyer, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani, declared in a TV interview: “Truth isn’t truth.” A few months later, a talking head defended a critical news report on the grounds that, just because it is “not accurate doesn’t mean it’s not true.”

It testifies both to the brilliance of Orwell’s vision and to the bane of our times that Nineteen Eighty-Four retains so much relevance.

John Rodden and John Rossi, “George Orwell Warned Us, But Was Anyone Listening?”, The American Conservative, 2019-10-02.

October 30, 2019

QotD: Trotskyism

[The word “Trotskyist”] is used so loosely as to include Anarchists, democratic Socialists and even Liberals. I use it here to mean a doctrinaire Marxist whose main motive is hostility to the Stalin regime. Trotskyism can be better studied in obscure pamphlets or in papers like the Socialist Appeal than in the works of Trotsky himself, who was by no means a man of one idea. Although in some places, for instance in the United States, Trotskyism is able to attract a fairly large number of adherents and develop into an organised movement with a petty fuehrer of its own, its inspiration is essentially negative. The Trotskyist is against Stalin just as the Communist is for him, and, like the majority of Communists, he wants not so much to alter the external world as to feel that the battle for prestige is going in his own favour. In each case there is the same obsessive fixation on a single subject, the same inability to form a genuinely rational opinion based on probabilities. The fact that Trotskyists are everywhere a persecuted minority, and that the accusation usually made against them, i.e. of collaborating with the Fascists, is obviously false, creates an impression that Trotskyism is intellectually and morally superior to Communism; but it is doubtful whether there is much difference. The most typical Trotskyists, in any case, are ex-Communists, and no one arrives at Trotskyism except via one of the left-wing movements. No Communist, unless tethered to his party by years of habit, is secure against a sudden lapse into Trotskyism. The opposite process does not seem to happen equally often, though there is no clear reason why it should not.George Orwell, “Notes on Nationalism”, Polemic, 1945-05.

October 20, 2019

QotD: Why Orwell wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four

Many thanks for your letter. You ask whether totalitarianism, leader-worship etc. are really on the up-grade and instance the fact that they are not apparently growing in this country and the USA.I must say I believe, or fear, that taking the world as a whole these things are on the increase. Hitler, no doubt, will soon disappear, but only at the expense of strengthening (a) Stalin, (b) the Anglo-American millionaires and (c) all sorts of petty führers of the type of de Gaulle. All the national movements everywhere, even those that originate in resistance to German domination, seem to take non-democratic forms, to group themselves round some superhuman führer (Hitler, Stalin, Salazar, Franco, Gandhi, De Valera are all varying examples) and to adopt the theory that the end justifies the means. Everywhere the world movement seems to be in the direction of centralised economies which can be made to “work” in an economic sense but which are not democratically organised and which tend to establish a caste system. With this go the horrors of emotional nationalism and a tendency to disbelieve in the existence of objective truth because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible führer. Already history has in a sense ceased to exist, ie. there is no such thing as a history of our own times which could be universally accepted, and the exact sciences are endangered as soon as military necessity ceases to keep people up to the mark. Hitler can say that the Jews started the war, and if he survives that will become official history. He can’t say that two and two are five, because for the purposes of, say, ballistics they have to make four. But if the sort of world that I am afraid of arrives, a world of two or three great superstates which are unable to conquer one another, two and two could become five if the führer wished it. That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible.

As to the comparative immunity of Britain and the USA. Whatever the pacifists etc. may say, we have not gone totalitarian yet and this is a very hopeful symptom. I believe very deeply, as I explained in my book The Lion and the Unicorn, in the English people and in their capacity to centralise their economy without destroying freedom in doing so. But one must remember that Britain and the USA haven’t been really tried, they haven’t known defeat or severe suffering, and there are some bad symptoms to balance the good ones. To begin with there is the general indifference to the decay of democracy. Do you realise, for instance, that no one in England under 26 now has a vote and that so far as one can see the great mass of people of that age don’t give a damn for this? Secondly there is the fact that the intellectuals are more totalitarian in outlook than the common people. On the whole the English intelligentsia have opposed Hitler, but only at the price of accepting Stalin. Most of them are perfectly ready for dictatorial methods, secret police, systematic falsification of history etc. so long as they feel that it is on “our” side. Indeed the statement that we haven’t a Fascist movement in England largely means that the young, at this moment, look for their führer elsewhere. One can’t be sure that that won’t change, nor can one be sure that the common people won’t think ten years hence as the intellectuals do now. I hope they won’t, I even trust they won’t, but if so it will be at the cost of a struggle. If one simply proclaims that all is for the best and doesn’t point to the sinister symptoms, one is merely helping to bring totalitarianism nearer.

You also ask, if I think the world tendency is towards Fascism, why do I support the war. It is a choice of evils — I fancy nearly every war is that. I know enough of British imperialism not to like it, but I would support it against Nazism or Japanese imperialism, as the lesser evil. Similarly I would support the USSR against Germany because I think the USSR cannot altogether escape its past and retains enough of the original ideas of the Revolution to make it a more hopeful phenomenon than Nazi Germany. I think, and have thought ever since the war began, in 1936 or thereabouts, that our cause is the better, but we have to keep on making it the better, which involves constant criticism.

George Orwell, responding to a letter from Noel Willmett, 1944-05-18.

October 6, 2019

The cultural influence of George Orwell

George Orwell, the chosen pen name of Eric Blair, is one of the best known writers of the 20th century and even people who have never read any of his writings are aware of his influence. John Rodden and John Rossi outline the immediate post-war period that saw Orwell publish his final and best-known work:

Seven decades ago on June 8, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four exploded on the cultural front—fittingly enough, just two months before the Soviet Union’s first successful atomic test that August, which broke America’s nuclear monopoly. Orwell’s warning was urgent — and timely. Almost overnight, in the wake of the surrender of Germany and Japan that ended World War II in 1945, a new war—the so-called Cold War — had emerged. (Orwell is often credited with coining the term.)

The Cold War pitted the capitalist West against the communist East, above all the United States against the USSR (and soon China). Just three weeks before the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Soviet Union lifted the Berlin Blockade, thereby avoiding a potentially deadly showdown with the West that might have triggered World War III. Two weeks later, on May 23, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) was officially established, effectively ending prospects in the near future of German reunification. On the very day of Nineteen Eighty-Four‘s publication, June 8, fears swept through liberal America of a growing Red Scare when a leaked document named numerous celebrities as Communist Party members (e.g., Helen Keller, Dorothy Parker, Fredric March, Danny Kaye, Edward G. Robinson). That same month, the communist armies of Mao Zedong captured Shanghai, and less than six months later on October 1, declared victory in the civil war against the American-backed Nationalists and the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

What educated person is not at least vaguely familiar with the language and vision of Orwell’s novel — even if he or she does not recognize the source? Indeed the very ignorance of the source represents an inadvertent tribute to the power of Orwell’s language and vision. Like Shakespeare’s poetry (“All the world’s a stage,” “To be or not to be,” “This above all: to thine own self be true”), so deeply have some of Orwell’s locutions become lodged in the cultural lexicon and political imagination that most people no longer recognize their author, let alone the source.

Today, as in the case of Shakespeare, hundreds of millions of people mouth Orwell’s coinages and catchphrases, such as “Big Brother” and “doublethink” — including his name as proper adjective, “Orwellian” (i.e., nightmarish, oppressive). And that’s just in English. Tens of millions more recognize and repeat them in foreign translations, as I [Rodden] discovered in our travels and teaching in the communist East Germany as well as in Asia. Rudimentary acquaintance with such locutions is regarded as a sine qua non of cultural literacy in English — even today, when prolefeed (mindless chatter) floods the print columns and dominates the airwaves.

Nineteen Eighty-Four represents Orwell’s Orwellian vision — in the form of a fictional anti-utopia (or “dystopia”) — of what a nightmarish, oppressive future might hold. It projects a world 35 years away — half the biblical lifespan of three score and ten. Having completed his novel by the end of 1948, Orwell flipped the last two digits to underscore his anti-utopian theme of a world turned upside down and inside out. Or so many scholars have reasonably claimed. The date resultant from the flipped digits also gave the novel its immediacy. Previous anti-utopias, such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), had cast their ominous scenarios far into the future, which lessened their dramatic impact and tended to render them entertaining thought experiments. (Huxley’s action is set in the 26th century.) By contrast, Orwell’s dire future is too close for comfort — and depicts the planet in the immediate aftermath of a global nuclear war that has nearly annihilated the human species. His vision thus projects a world in which middle-aged readers in 1949 might find themselves in old age — and certainly their children and grandchildren were likely to witness it. (If he had lived, Orwell himself would have still been just 80 years old on April 4, 1984, when the story opens.)

September 27, 2019

A visual masterclass in trolling

For all that Donald Trump is known for trolling his opponents on Twitter, he’s certainly not the only one, as these makeshift posters in Massachusetts illustrate:

The locals are outraged, but as Alaa Al-Ameri describes, they’re not quite sure how to safely express their fury:

Think of Posie Parker’s billboards quoting the dictionary definition of the word “woman”. The power of such acts comes from two things. First, they acknowledge – usually with irreducible simplicity – that something that went without saying a moment ago has suddenly become unsayable. Secondly, the outrage they provoke does not come from any epithet, caricature or insult, but rather from having the nerve to draw the viewer’s attention to an act of cognitive dissonance that we are all engaging in, but would rather not acknowledge.

The result is that those who attempt to explain why the act is offensive end up simply tying themselves in knots, while revealing that they have never given a moment’s thought to the position they find themselves defending. This seems to generate even more anger, with the inevitable online mob quickly joined by politicians, journalists and other public figures, eager to see that the heretic is made an example of.

At their best, these acts of public disobedience are examples of real-life Winston Smiths pointing out to the rest of us that “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four”. Their persecutors, like his, are those who know and fear the truth of Smith’s next sentence: “If that is granted, all else follows.”

The example of perfectly crafted dissent that I’d like to submit here appears in this video from Massachusetts local TV news, showing some reactions to the fly-posting of white sheets of paper bearing the statement “Islam is right about women”. The reactions are deeply revealing. Nobody can clearly point out why they object to the statement – indeed, nobody seems to object to the statement at all on its face. Yet most seem to express offence at it – if a little unconvincingly.

The reason for their dilemma is obvious enough to anyone who has been paying attention. Western society has managed to convince itself (at least in public) that any statement criticising any aspect of Islam is, by definition, bigotry. As a result, Western societies have effectively decided to enforce Islamic restrictions on blasphemy, and called it “tolerance”.

The strain of conforming to this lie is evident in the fumbling attempts by the interviewees to explain their objections. Do they believe that Islam is right about women? If so, why the objection? Do they believe that Islam is wrong about women? If so, in what sense is the statement an attack on Islam or Muslims? Do they believe that the author of the poster is saying that “Islam is right about women”, but doing so ironically? In which case, the objection can only be that the author is guilty of a thoughtcrime by stating that “two and two make five” with insufficient sincerity. Or do they worry that they are guilty of thoughtcrime for noticing the irony?

September 13, 2019

QotD: Orwell’s campaign against the jackboot

In spite of my campaign against the jackboot — in which I am not operating single-handed — I notice that jackboots are as common as ever in the columns of the newspapers. Even in the leading articles in the Evening Standard, I have come upon several of them lately. But I am still without any clear information as to what a jackboot is. It is a kind of boot that you put on when you want to behave tyrannically: that is as much as anyone seems to know.

Others besides myself have noted that war, when it gets into the leading articles, is apt to be waged with remarkably old-fashioned weapons. Planes and tanks do make occasional appearances, but as soon as an heroic attitude has to be struck, the only armaments mentioned are the sword (“We shall not sheathe the sword until”, etc., etc.), the spear, the shield, the buckler, the trident, the chariot and the clarion. All of these are hopelessly out of date (the chariot, for instance, has not been in effective use since about A.D. 50), and even the purpose of some of them has been forgotten. What is a buckler, for instance? One school of thought holds that it is a small round shield, but another school believes it to be a kind of belt. A clarion, I believe, is a trumpet, but most people imagine that a “clarion call” merely means a loud noise. One of the early Mass Observation reports, dealing with the coronation of George VI, pointed out that what are called “national occasions” always seem to cause a lapse into archaic language. The “ship of state”, for instance, when it makes one of its official appearances, has a prow and a helm instead of having a bow and a wheel, like modern ships. So far as it is applied to war, the motive for using this kind of language is probably a desire for euphemism. “We will not sheathe the sword” sounds a lot more gentlemanly than “We will keep on dropping block-busters”, though in effect it means the same.

One argument for Basic English is that by existing side by side with Standard English it can act as a sort of corrective to the oratory of statesmen and publicists. High-sounding phrases, when translated into Basic, are often deflated in a surprising way. For example, I presented to a Basic expert the sentence, “He little knew the fate that lay in store for him” — to be told that in Basic this would become “He was far from certain what was going to happen”. It sounds decidedly less impressive, but it means the same. In Basic, I am told, you cannot make a meaningless statement without its being apparent that it is meaningless — which is quite enough to explain why so many schoolmasters, editors, politicians and literary critics object to it.

George Orwell, “As I Please” Tribune, 1944-08-04.

September 11, 2019

Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments

Colby Cosh discusses the genesis of Atwood’s best-known work from 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale and the new sequel published this week, The Testaments:

In a CBS interview broadcast on Sunday, Atwood insisted again, as she always has, that her book wasn’t a prediction. People who read her book in a spirit of active dread, the kind of people who dress up as Handmaids and march on legislatures, will say that, well, dystopias are created specifically so that they won’t come true. What Atwood is trying to say goes deeper than that, and contradicts it. She won’t even insist that the book was intended as a warning. “I’m not a prophet,” she pleads, while everyone around her tells her what a terrific prophet she is.

What she means, but cannot say because it would sound arrogant, is: “I’m not a prophet, dammit, I’m an artist.” If tyrannies were easy to predict and prevent by spritzing around a bit of literary bug spray, they couldn’t come about in the first place. Atwood knows better than this; she knows that tragedies of this scale never take the form that an author might anticipate. Moreover, people who read The Handmaid’s Tale as a mere tract are deaf to its satirical elements — particularly those of the epilogue, in which the story is revealed to have been unearthed by scholars in a still-more-distant future.These people are also failing to see that The Handmaid’s Tale is a book — researched, not merely imagined — about the past of humankind. The whole book is predicated on the observation (also made implicitly in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four) that totalitarian regimes are never libertine; they all police sexuality at least as strenuously as they do trade and creative activity, and always come with puritanical, sexually homogenizing features. The novel was heavily influenced by Ceausescu’s Romania and its pro-natalist Decree 770, which abolished contraception and imposed mass gynecological inspection on women of fertile age. Europeans and students (or veterans) of the Cold War will notice this, but how many of the young folk who dress up as Handmaids at protests have any idea? (Are some of them also cosplaying on Twitter as postmodern retro-communists?)

I am curious to see what the critics make of the sequel, because the act of writing one seems a bit cynical, and yet perhaps Atwood has found some clever way of making it work. Offred’s narrative in The Handmaid’s Tale is, as I say, unearthed in a later future; it is important to the functioning of the book that we come to see her as a figure from the past, a human voice whose plea from an obscure period has been flung forward into the hands of half-comprehending and unsympathetic scholarly boobs.

September 3, 2019

QotD: Fencing out the London poor

I see that the railings are returning — only wooden ones, it is true, but still railings — in one London square after another. So the lawful denizens of the squares can make use of their treasured keys again, and the children of the poor can be kept out.When the railings round the parks and squares were removed, the object was partly to accumulate scrap-iron, but the removal was also felt to be a democratic gesture. Many more green spaces were now open to the public, and you could stay in the parks till all hours instead of being hounded out at closing times by grim-faced keepers. It was also discovered that these railings were not only unnecessary but hideously ugly. The parks were improved out of recognition by being laid open, acquiring a friendly, almost rural look that they had never had before. And had the railings vanished permanently, another improvement would probably have followed. The dreary shrubberies of laurel and privet — plants not suited to England and always dusty, at any rate in London — would probably have been grubbed up and replaced by flower beds. Like the railings, they were merely put there to keep the populace out. However, the higher-ups managed to avert this reform, like so many others, and everywhere the wooden palisades are going up, regardless of the wastage of labour and timber.

George Orwell, “As I Please” Tribune, 1944-08-04.

August 30, 2019

QotD: Racism in London during WW2

A few days ago a West African wrote to inform us that a certain London dance hall had recently erected a “colour bar”, presumably in order to please the American soldiers who formed an important part of its clientele. Telephone conversations with the management of the dance hall brought us the answers: (a) that the “colour bar” had been cancelled, and (b) that it had never been imposed in the first place; but I think one can take it that our informant’s charge had some kind of basis. There have been other similar incidents recently. For instance, I during last week a case in a magistrate’s court brought out the fact that a West Indian Negro working in this country had been refused admission to a place of entertainment when he was wearing Home Guard uniform. And there have been many instances of Indians, Negroes and others being turned away from hotels on the ground that “we don’t take coloured people”.It is immensely important to be vigilant against this kind of thing, and to make as much public fuss as possible whenever it happens. For this is one of those matters in which making a fuss can achieve something. There is no kind of legal disability against coloured people in this country, and, what is more, there is very little popular colour feeling. (This is not due to any inherent virtue in the British people, as our behaviour in India shows. It is due to the fact that in Britain itself there is no colour problem.)

The trouble always arises in the same way. A hotel, restaurant or what-not is frequented by people who have money to spend who object to mixing with Indians or Negroes. They tell the proprietor that unless he imposes a colour bar they will go elsewhere. They may be a very small minority, and the proprietor may not be in agreement with them, but it is difficult for him to lose good customers; so he imposes the colour bar. This kind of thing cannot happen when public opinion is on the alert and disagreeable publicity is given to any establishment where coloured people are insulted. Anyone who knows of a provable instance of colour discrimination ought always to expose it. Otherwise the tiny percentage of colour-snobs who exist among us can make endless mischief, and the British people are given a bad name which, as a whole, they do not deserve.

In the nineteen-twenties, when American tourists were as much a part of the scenery of Paris as tobacco kiosks and tin urinals, the beginnings of a colour bar began to appear even in France. The Americans spend money like water, and restaurant proprietors and the like could not afford to disregard them. One evening, at a dance in a very well-known cafe some Americans objected to the presence of a Negro who was there with an Egyptian woman. After making some feeble protests, the proprietor gave in, and the Negro was turned out.

Next morning there was a terrible hullabaloo and the cafe proprietor was hauled up before a Minister of the Government and threatened with prosecution. It had turned out that the offended Negro was the Ambassador of Haiti. People of that kind can usually get satisfaction, but most of us do not have the good fortune to be ambassadors, and the ordinary Indian, Negro or Chinese can only be protected against petty insult if other ordinary people are willing to exert themselves on his behalf.

George Orwell, “As I Please” Tribune, 1944-08-11.

August 27, 2019

QotD: Salvador Dali and the “benefit of clergy”

Now, if you showed this book, with its illustrations, to Lord Elton, to Mr. Alfred Noyes, to The Times leader writers who exult over the “eclipse of the highbrow” — in fact, to any “sensible” art-hating English person — it is easy to imagine what kind of response you would get. They would flatly refuse to see any merit in Dali whatever. Such people are not only unable to admit that what is morally degraded can be aesthetically right, but their real demand of every artist is that he shall pat them on the back and tell them that thought is unnecessary. And they can be especially dangerous at a time like the present, when the Ministry of Information and the British Council put power into their hands. For their impulse is not only to crush every new talent as it appears, but to castrate the past as well. Witness the renewed highbrow-baiting that is now going on in this country and America, with its outcry not only against Joyce, Proust and Lawrence, but even against T. S. Eliot.

But if you talk to the kind of person who can see Dali’s merits, the response that you get is not as a rule very much better. If you say that Dali, though a brilliant draughtsman, is a dirty little scoundrel, you are looked upon as a savage. If you say that you don’t like rotting corpses, and that people who do like rotting corpses are mentally diseased, it is assumed that you lack the aesthetic sense. Since Mannequin rotting in a taxicab is a good composition. And between these two fallacies there is no middle position, but we seldom hear much about it. On the one side Kulturbolschevismus: on the other (though the phrase itself is out of fashion) “Art for Art’s sake.” Obscenity is a very difficult question to discuss honestly. People are too frightened either of seeming to be shocked or of seeming not to be shocked, to be able to define the relationship between art and morals.

It will be seen that what the defenders of Dali are claiming is a kind of benefit of clergy. The artist is to be exempt from the moral laws that are binding on ordinary people. Just pronounce the magic word “Art”, and everything is O.K.: kicking little girls in the head is O.K.; even a film like L’Age d’Or* is O.K. It is also O.K. that Dali should batten on France for years and then scuttle off like rat as soon as France is in danger. So long as you can paint well enough to pass the test, all shall be forgiven you.

One can see how false this is if one extends it to cover ordinary crime. In an age like our own, when the artist is an altogether exceptional person, he must be allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility, just as a pregnant woman is. Still, no one would say that a pregnant woman should be allowed to commit murder, nor would anyone make such a claim for the artist, however gifted. If Shakespeare returned to the earth to-morrow, and if it were found that his favourite recreation was raping little girls in railway carriages, we should not tell him to go ahead with it on the ground that he might write another King Lear. And, after all, the worst crimes are not always the punishable ones. By encouraging necrophilic reveries one probably does quite as much harm as by, say, picking pockets at the races. One ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dali is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being. The one does not invalidate or, in a sense, affect the other. The first thing that we demand of a wall is that it shall stand up. If it stands up, it is a good wall, and the question of what purpose it serves is separable from that. And yet even the best wall in the world deserves to be pulled down if it surrounds a concentration camp. In the same way it should be possible to say, “This is a good book or a good picture, and it ought to be burned by the public hangman.” Unless one can say that, at least in imagination, one is shirking the implications of the fact that an artist is also a citizen and a human being.

* Dali mentions L’Age d’Or and adds that its first public showing was broken up by hooligans, but he does not say in detail what it was about. According to Henry Miller’s account of it, it showed among other things some fairly detailed shots of a woman defecating.

George Orwell, “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali”, Saturday Book for 1944, 1944.

August 23, 2019

QotD: The ego of Salvador Dali

[Dali’s] aberrations are partly explicable. Perhaps they are a way of assuring himself that he is not commonplace. The two qualities that Dali unquestionably possesses are a gift for drawing and an atrocious egoism. “At seven”, he says in the first paragraph of his book, “I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily ever since.” This is worded in a deliberately startling way, but no doubt it is substantially true. Such feelings are common enough. “I knew I was a genius”, somebody once said to me, “long before I knew what I was going to be a genius about.” And suppose that you have nothing in you except your egoism and a dexterity that goes no higher than the elbow; suppose that your real gift is for a detailed, academic, representational style of drawing, your real métier to be an illustrator of scientific textbooks. How then do you become Napoleon?

There is always one escape: into wickedness. Always do the thing that will shock and wound people. At five, throw a little boy off a bridge, strike an old doctor across the face with a whip and break his spectacles — or, at any rate, dream about doing such things. Twenty years later, gouge the eyes out of dead donkeys with a pair of scissors. Along those lines you can always feel yourself original. And after all, it pays! It is much less dangerous than crime. Making all allowance for the probable suppressions in Dali’s autobiography, it is clear that he had not had to suffer for his eccentricities as he would have done in an earlier age. He grew up into the corrupt world of the nineteen-twenties, when sophistication was immensely widespread and every European capital swarmed with aristocrats and rentiers who had given up sport and politics and taken to patronising the arts. If you threw dead donkeys at people, they threw money back. A phobia for grasshoppers — which a few decades back would merely have provoked a snigger — was now an interesting “complex” which could be profitably exploited. And when that particular world collapsed before the German Army, America was waiting. You could even top it all up with religious conversion, moving at one hop and without a shadow of repentance from the fashionable salons of Paris to Abraham’s bosom.

That, perhaps is the essential outline of Dali’s history. But why his aberrations should be the particular ones they were, and why it should be so easy to “sell” such horrors as rotting corpses to a sophisticated public — those are questions for the psychologist and the sociological critic. Marxist criticism has a short way with such phenomena as Surrealism. They are “bourgeois decadence” (much play is made with the phrases “corpse poisons” and “decaying rentiers class”), and that is that. But though this probably states a fact, it does not establish a connection. One would still like to know why Dali’s leaning was towards necrophilia (and not, say, homosexuality), and why the rentiers and the aristocrats would buy his pictures instead of hunting and making love like their grandfathers. Mere moral disapproval does not get one any further. But neither ought one to pretend, in the name of “detachment”, that such pictures as Mannequin rotting in a taxicab are morally neutral. They are diseased and disgusting, and any investigation ought to start out from that fact.

George Orwell, “Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali”, Saturday Book for 1944, 1944.