Rob Henderson wonders why so many adults these days are clearly desperate for the approval of young people:

During my recent re-watch of the entirety of Mad Men, which takes place in the 1960s, a recurring thought entered my mind: This was the last generation where young adults behaved like they were older than their real age. Don Draper is around thirty-five at the start of the series, and carries himself in a more adult manner than many 45 year olds today.

Recently, Abigail Shrier quoted a physician and psychologist who stated that “Fifty years ago, boys wanted to be men. But today, many American men want to be boys”.

Until the early 1960s, young people acted older than their actual age. Now, older adults pretend to be younger than their actual age.

Which is perhaps one reason why boomers are so easy to mock. They don’t act their age.

[…]

About two years later, I was at a breakfast gathering with some other students on campus. Our guest was a former governor and presidential candidate. He was gracious, and spent most of the time answering questions from students.

And in his answers, he continually returned to variations of the same response: “We screwed up, and it’s up to you guys to fix it. I’m so happy to see how bright you all are and how sharp your questions have been, because you will fix the mistakes my generation made.”

This mystified me. This guy was well into his sixties, with a lifetime of unique experiences in leadership roles, was telling a bunch of 20-year-olds (though I was a little older) that older adults are relying on them.

In the military, we thought of those senior to us as the leaders. It was okay to give feedback, of course. Commanding officers would regularly consult lower ranking and enlisted members to see what was working and what could be improved. But that happens only after getting through the filter of the initial training endeavors.

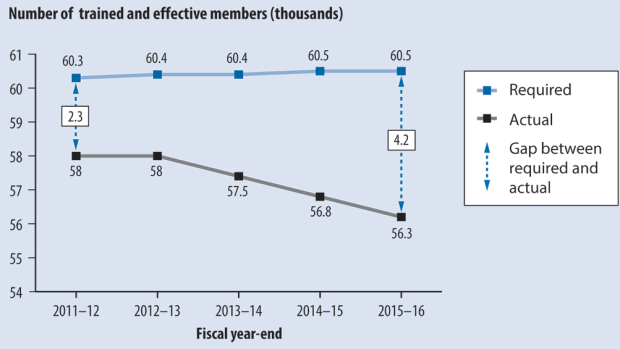

I remember in the first week of basic training, our instructor declared, “I don’t want any of you [expletive] thinking you are doing anyone a favor being here. I could get rid of all of you clowns and have your replacements here within the hour.” (This was 2007, well before the recruitment crisis).

My 17-year-old brain heard that thought, yeah, he’s probably right. I thought of the bus loads of other ungainly young guys I saw stepping off and being confronted with “Pick ’em up, and put ’em down” and other mind games from the instructors while waiting in the endless in-processing lines.

So then I got to college and learned that even though any seat, at least at selective schools, can be filled immediately with a bright applicant (top colleges reject thousands of them each year), students are never ejected for disrespecting professors or anyone else. In the military the first message was, you are a peon and less than nothing and we can easily have you replaced (this changes as you advance in rank, of course — at least to some degree). In college, the first message was, you are amazing and privileged and a future leader (and marginalized and erased) and you will never lose your position here among the future ruling class. That feeling of whiplash will forever linger in my mind.

[…]

Older adults crave validation from the youth, which is one reason they are mocked. Young people sense their desire to be seen as cool and deprive them of this by taunting them.

This desire for esteem may be why older adults won’t exert any authority in response to energetic young conflict entrepreneurs who yell at them or threaten them.

Older adults want to be on the side of youth. So desperate to pencil themselves out of the “old” category. Every parent wants to be the “cool parent”, every professor wants to be the “cool” professor. You can be cool and still be an authority figure. Maybe decades of imbibing the worst of U.S. pop culture made everyone forget this.