Agriculture created a stationary population that both wouldn’t move but which could also be dominated, subjugated and have their production extracted from them. Their wealth was clustered in towns which could be fortified with walls that would resist any quick raid, but control of that fortified town center (and its administrative apparatus of taxation) meant control of the countryside and its resources. Taking such a town meant a siege – delivering a large body of troops and keeping them there long enough to either breach the walls or starve the town into surrender. This created a war where territorial control was defined by the taking of fixed points.

In such war, the goal was to deliver the siege. But delivery of the siege meant a large army which might now be confronted in the field (for it was unlikely to move by stealth, being that it has to be large enough to take the town). And so to prohibit the siege from being delivered, defenders might march out and meet the attackers in the field for that pitched battle. In certain periods, siegecraft or army size had so outpaced fortress design that everyone rather understood that after the outcome of the pitched battle, the siege would be a forgone conclusion – it is that unusual state of affairs which gives us the “decisive battle” where a war might potentially be ended in a stoke (though they rarely were).

We may term this the second system of war. It is the system that most modern industrial and post-industrial cultures are focused on. Our cultural products are filled with such pitched battles, placed in every sort of era of our past or speculative future. It is how we imagine war. Except that it isn’t the sort of war we wage, is it?

Because in the early 1900s, the industrial revolution resulted in armies possessing both amounts of resources and levels of industrial firepower which precluded open pitched battles. All of those staples of our cultural fiction of battles, developed from the second system – surveying the enemy army drawn up in battle array, the tense wait, then the furious charge, coming to grips with the enemy in masses close up – none of that could survive modern machine guns and artillery.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIa: The Many Faces of Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

May 31, 2023

QotD: The second system of war

May 4, 2023

Fierce fighting on Gallipoli … before WW1

Bruce Gudmundsson outlines the operations of Ottoman Empire forces defending “Turkey in Europe” against Greek and Bulgarian invasion (in alliance with Serbia and Montenegro) in 1913:

In the English speaking world, the name Gallipoli invariably evokes memories of the great events of 1915 and 1916. A location of such strategic importance, however, rarely serves as the site of a single battles. Two years before the landings of the British, Indian, Australian, and New Zealand troops on the south-west portion of the the peninsula (and the concurrent French landings on the nearby mainland of Asia Minor near the ruins of the ancient city of Troy), Ottoman soldiers defended the Dardanelles against the forces of the Balkan League.

By the end of January of 1913, the combined efforts of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria had driven Ottoman forces from most of “Turkey in Europe”. Indeed, the only intact Ottoman formations on European soil were those trapped in the fortress of Adrianople, those holding the fortified line just west of Constantinople, and those that had recently arrived at Gallipoli.

Soon after arriving, the Ottoman forces on Gallipoli began to build a belt of field fortifications across the narrowest part of the peninsula, a line some five kilometers (three miles) west of the the town of Bolayir. At the same time, they occupied outposts some twenty kilometers east of the line, at the place where the peninsula connected to the mainland.

On 4 February 1913, the Bulgarians attacked. On the first day of this attack, they drove in the Ottoman outposts. On the second day, they broke through a hastily erected line of resistance, thereby convincing the Ottoman forces in front of them to evacuate Bolayir. However, rather than taking the town, or otherwise attempting to exploit their victory, they withdrew to positions some ten kilometers (six miles) east of the Ottoman earthworks.

While the Ottoman land forces returned to the earthworks along the neck of the Peninsula, ships of the Ottoman Navy operating in the Sea of Marmora located, and began to bombard, the Bulgarian forces near the coast. This caused the Bulgarians to move inland, where they took up, and improved, new positions on the rear slopes of nearby hills.

On 9 February, the Ottomans launched a double attack. While the main body of the Ottoman garrison of Gallipoli advanced overland, a smaller force, supported by the fire of Ottoman warships, landed on the far side of the Bulgarian position. Notwithstanding the advantages, both numerical and geometric, enjoyed by the Ottoman attackers, this pincer action failed to destroy the Bulgarian force. Indeed, in the course of two failed attacks, the Ottomans suffered some ten thousand casualties.

Though the Ottoman maneuver failed to dislodge the Bulgarians from their trenches, the two-sided attack convinced the Bulgarian commander to seek ground that was, at once, both easier to defend against terrestrial attack and less vulnerable to naval gunfire. He found this on the east bank of a river, thirteen kilometers (eight miles) northeast of Bolayir and ten kilometers (six miles) north of the place where the Ottoman landing had taken place.

April 29, 2023

What Was the Deadliest Day of the First World War?

The Great War

Published 28 Apr 2023What was the deadliest day of any nation in WW1? There are multiple candidates for that, but why should we even care? Well, the answer to this question highlights a challenge with popular memory that is often focused on the biggest battles of the war like the Somme or Verdun.

(more…)

April 10, 2023

1970: Welcome to SEALAND | Nationwide | Voice of the People | BBC Archive

BBC Archive

Published 18 Dec 2022Nationwide‘s Bob Wellings is winched up to meet the Bates, the first family of the Principality of Sealand.

Formerly HM Fort Roughs, Sealand is a concrete and iron platform in the North Sea about seven miles off the Suffolk coast. What has drawn the family to this remote place? How does living in such an unusual environment effect their day-to-day life? What are their plans for it?

Originally broadcast 19 March, 1970.

(more…)

March 29, 2023

The obscure Polish banker who foresaw the carnage and deadlock of the First World War

Jon Miltimore on one of the few people to realize the increased deadliness and growing size of modern armies foreclosed any possibility of a quick, glorious war that would have the troops “home for Christmas”:

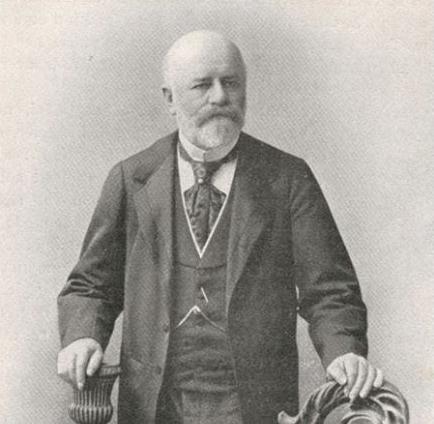

Jan Bloch, author of The War of the Future in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations (1898).

One man who did portend the carnage was Jan Bloch, a Polish banker and railroad baron who moonlighted as a military theorist. In 1898, Bloch published a little-noticed six-volume work titled The War of the Future in its Technical, Economic and Political Relations. The following year, the work was re-published in a single volume under a new title: Is War Now Impossible?

In the work, Bloch, who had closely studied Britain’s campaign in Africa during the Boer War, explained that modern weaponry had become so deadly that it had fundamentally changed warfare. Bayonet charges and cavalry flanking maneuvers were obsolete in an era defined by sophisticated earthworks and precision projectiles, he suggested.

Everybody will be entrenched in the next war. It will be a great war of entrenchments. The spade will be as indispensable to a soldier as his rifle. The first thing every man will have to do, if he cares for his life at all, will be to dig a hole in the ground. War, instead of being a hand-to-hand contest in which the combatants measure their physical and moral superiority, will become a kind of stalemate, in which neither army is able to get at the other, threatening each other, but never being able to deliver a final and decisive attack.

War would be “impossible” in the sense that it would be suicidal. Neither side would be able to gain a decisive advantage, battles along massive contiguous fronts would continue indefinitely.

Was Bloch suggesting that modern man had vanquished war by making it so deadly and terrible? Hardly. He argued that humans would be slow to realize the changes, and the results would be catastrophic.

At first there will be increased slaughter — increased slaughter on so terrible a scale as to render it impossible to get troops to push the battle to a decisive issue. They will try to, thinking that they are fighting under the old conditions, and they will learn such a lesson that they will abandon the attempt forever. Then, instead of war fought out to the bitter end in a series of decisive battles, we shall have as a substitute a long period of continually increasing strain upon the resources of the combatants. The war, instead of being a hand-to-hand contest, in which the combatants measure their physical and moral superiority, will become a kind of stalemate, in which neither army being willing to get at the other, both armies will be maintained in opposition to each other, threatening the other, but never being able to deliver a final and decisive attack …

That is the future of war — not fighting, but famine, not the slaying of men, but the bankruptcy of nations and the breakup of the whole social organization …

First World War generals don’t get much credit for their varied efforts to break the trench warfare deadlock, and later historians certainly piled on for the leaders’ collective failure to resolve the problem, but as Bret Devereaux pointed out, there was no easy solution. Artillery wasn’t the answer, nor were the famed German Stoßtruppen, nor the technical innovation of tanks, nor air power (either tactical or strategic). The technology of the day provide no one answer, but the leaders tried everything they could and the bleeding went on.

February 9, 2023

QotD: Collecting taxes, Medieval-style

I want to begin with an observation, obvious but frequently ignored: states are complex things. The apparatus by which a state gathers revenue, raises armies (with that revenue), administers justice and tries to organize society – that apparatus requires people. Not just any people: they need to be people of the educated, literate sort to be able to record taxes, read the laws and transmit (written) royal orders and decrees.

(Note: for a more detailed primer on what this kind of apparatus can look like, check out Wayne Lee’s (@MilHist_Lee) talk “Reaping the Rewards: How the Governor, the Priest, the Taxman, and the Garrison Secure Victory in World History” here. He’s got some specific points he’s driving at, but the first half of the talk is a broad overview of the problems you face as a suddenly successful king. Also, the whole thing is fascinating.)

In a pre-modern society, this task – assembling and organizing the literate bureaucrats you need to run a state – is very difficult. Literacy is often very low, so the number of individuals with the necessary skills is minuscule. Training new literate bureaucrats is expensive, as is paying the ones you have, creating a catch-22 where the king has no money because he has no tax collectors and he has no tax collectors because he has no money. Looking at how states form is thus often a question of looking at how this low-administration equilibrium is broken. The administrators you need might be found in civic elites who are persuaded to do the job in exchange for power, or in a co-opted religious hierarchy of educated priests, for instance.

Vassalage represents another response to the problem, which is the attempt to – as much as possible – do without. Let’s specify terms: I am using “vassalage” here because it is specific in a way that the more commonly used “feudalism” is not. I am not (yet) referring to how peasants (in Westeros the “smallfolk”) interact with lords (which is better termed “manorialism” than as part of feudalism anyway), but rather how military aristocrats (knights, lords, etc) interact with each other.

So let us say you are a king who has suddenly come into a lot of land, probably by bloody conquest. You need to extract revenue from that land in order to pay for the armies you used to conquer it, but you don’t have a pile of literate bureaucrats to collect those taxes and no easy way to get some. By handing out that land to your military retainers as fiefs (they become your vassals), you can solve a bunch of problems at once. First, you pay off your military retainers for their service with something you have that is valuable (land). Second, by extracting certain promises (called “homage”) from them, you ensure that they will continue to fight for you. And third, you are partitioning your land into smaller and smaller chunks until you get them in chunks small enough to be administered directly, with only a very, very minimal bureaucratic apparatus. Your new vassals, of course, may do the same with their new land, further fragmenting the political system.

This is the system in Westeros, albeit after generations of inheritance (such that families, rather than individuals, serve as the chief political unit). The Westerosi term for a vassal is a “bannerman”. Greater military aristocrats with larger holding are lords, while lesser ones are landed knights. Landed knights often hold significant lands and a keep (fortified manner house), which would make them something more akin to European castellans or barons than, say, a 14th century English Knight Banneret (who is unlikely to have been given permission to fortify his home, known as a license to crenellate). What is missing from this system are the vast majority of knights, who would not have had any kind of fortified dwelling or castle, but would have instead been maintained as part of the household of some more senior member of the aristocracy. A handful of landless knights show up in Game of Thrones, but they should be by far the majority and make up most of the armies.

There’s one final missing ingredient here, which is castles, something Westeros has in abundance. Castles – in the absence of castle-breaking cannon – shift power downward in this system, because they allow vassals to effectively resist their lieges. That may not manifest in open rebellion so much as a refusal to go on campaign or supply troops. This is important, because it makes lieges as dependent on their vassals as vassals are on their lieges.

Bret Devereaux, “New Acquisitions: How It Wasn’t: Game of Thrones and the Middle Ages, Part III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-12.

January 22, 2023

Where The British Army Figured Out Tanks: Cambrai 1917

The Great War

Published 20 Jan 2023The Battle of Cambrai in 1917 didn’t have a clear winner, but the conclusions that Germany and Britain drew from it, particularly about the use of the tank (in combination with other arms), would have far reaching consequences in 1918.

(more…)

January 16, 2023

I thought the treadmill crane was fictional

Tom Scott

Published 26 Sep 2022The treadwheel crane, or treadmill crane, sounds like something from Astérix or the Flintstones. But at Guédelon in France, not only do they have one: they’re using it to help build their brand new castle.

▪ More about Guédelon: https://www.guedelon.fr/

(more…)

December 26, 2022

The Battle of Ortona with Jayson Geroux

OTD Canadian Military History

Published 21 Dec 2022Join me as I welcome Jayson Geroux to the OTD channel to discuss the Battle of Ortona. We will be discussing the urban combat that took place in Ortona in December 1943. [The discussion of the actual battle begins around the 6 minute mark.]

(more…)

December 25, 2022

Stalin’s Christmas Surprise – Major Offensives to Come – WW2 – 226 – December 24, 1943

World War Two

Published 24 Dec 2022Twas the night before Christmas and the war was grinding on. The Moro River Campaign continues in Italy with Canadian infantry pushing past the Gully and into “Little Stalingrad”. Generally, the Allied advance to Rome is turning into a stalemate though, but Winston Churchill still believes an amphibious landing is the way to break this. Joseph Stalin also has some pretty big plans to bring the USSR back to its pre-Barbarossa borders. In the Pacific, there is attrition over Rabaul and stalemate on Bougainville.

(more…)

December 3, 2022

“The Valley of Death” – The Battles of Doiran – Sabaton History 115

Sabaton History

Published 1 Dec 2022The Bulgarian defenses in the Lake Doiran region were pretty much the best defenses any country had anywhere in the Great War, which the Entente forces discovered as they tried time and again and failed time and again — to break the front.

(more…)

December 2, 2022

QotD: Rome’s legions settle down to permanent fortresses

The end of the reign of Augustus (in 14AD) is a convenient marker for a shift in Roman strategic aims away from expansion and towards a “frontier maintenance”. The usual term for both the Roman frontier and the system of fortifications and garrisons which defended it is the limes (pronounced “lim-ees”), although this wasn’t the only word the Romans applied to it. I want to leave aside for a moment the endless, complex conversation about the degree to which the Romans can actually be said to have strategic aims, though for what it is worth I am one of those who contends that they did. We’re mostly interested here in Roman behavior on the frontiers, rather than their intent anyway.

What absolutely does begin happening during the reign of Augustus and subsequently is that the Roman legions, which had spent the previous three centuries on the move outside of Italy, begin to settle down more permanently on Rome’s new frontiers, particularly along the Rhine/Danube frontier facing Central and Eastern Europe and the Syrian frontier facing the Parthian Empire. That in turn meant that Roman legions (and their supporting auxiliary cohorts) now settled into permanent forts.

The forts themselves, at least in the first two centuries, provide a fairly remarkably example of institutional inertia. While legionary forts of this early period typically replaced the earthwork-and-stakes wall (the agger and vallum) with stone walls and towers and the tents of the camp with permanent barracks, the basic form of the fort: its playing-card shape, encircling defensive ditches (now very often two or three ditches in sequence) remain. Of particular note, these early imperial legionary forts generally still feature towers which do not project outward from the wall, a stone version of the observation towers of the old Roman marching camp. Precisely because these fortifications are in stone they are often very archaeologically visible and so we have a fairly good sense of Roman forts in this period. In short then, put in permanent positions, Roman armies first constructed permanent versions of their temporary marching camps.

And that broadly seems to fit with how the Romans expected to fight their wars on these frontiers. The general superiority of Roman arms in pitched battle (the fancy term here is “escalation dominance” – that escalating to large scale warfare favored the heavier Roman armies) meant that the Romans typically planned to meet enemy armies in battle, not sit back to withstand sieges (this was less true on Rome’s eastern frontier since the Parthians were peer competitors who could rumble with the Romans on more-or-less even terms; it is striking that the major centers in the East like Jerusalem or Antioch did not get rid of their city walls, whereas by contrast the breakdown of Roman order in the third century AD and subsequently leads to a flurry of wall-building in the west where it is clear many cities had neglected their defensive walls for quite a long time). Consequently, the legionary forts are more bases than fortresses and so their fortifications are still designed to resist sudden raids, not large-scale sieges.

They were also now designed to support much larger fortification systems, which now gives us a chance to talk about a different kind of fortification network: border walls. The most famous of these Roman walls of course is Hadrian’s Wall, a mostly (but not entirely) stone wall which cuts across northern England, built starting in 122. Hadrian’s Wall is unusual in being substantially made out of stone, but it was of-a-piece with various Roman frontier fortification systems. Crucially, the purpose of this wall (and this is a trait it shares with China’s Great Wall) was never to actually prevent movement over the border or to block large-scale assaults. Taking Hadrian’s wall, it was generally manned by something around three legions (notionally; often at least one of the legions in Britain was deployed further south); even with auxiliary troops nowhere near enough to actually manage a thick defense along the entire wall. Instead, the wall’s purpose is slowing down hostile groups and channeling non-hostile groups (merchants, migrants, traders, travelers) towards controlled points of entry (valuable especially because import/export taxes were a key source of state revenue), while also allowing the soldiers on the wall good observation positions to see these moving groups. You can tell the defense here wasn’t prohibitive in part because the main legionary fortresses aren’t generally on the wall, but rather further south, often substantially further south, which makes a lot of sense if the plan is to have enemies slowed (but not stopped) by the wall, while news of their approach outraces them to those legionary forts so that the legions can form up and meet those incursions in an open battle after they have breached the wall itself. Remember: the Romans expect (and get) a very, very high success rate in open battles, so it makes sense to try to force that kind of confrontation.

This emphasis on controlling and channeling, rather than prohibiting, entry is even more visible in the Roman frontier defenses in North Africa and on the Rhine/Danube frontier. In North Africa, the frontier defense system was structured around watch-posts and the fossatum Africae, a network of ditches (fossa) separating the province of Africa (mostly modern day Tunisia) from non-Roman territory to its south. It isn’t a single ditch, but rather a system of at least four major segments (and possibly more), with watch-towers and smaller forts in a line-of-sight network (so they can communicate); the ditch itself varies in width and depth but typically not much more than 6m wide and 3m deep. Such an obstruction is obviously not an prohibitive defense but the difficulty of crossing is going to tend to channel travelers and raids to the intentional crossings or alternately slow them down as they have to navigate the trench (a real problem here where raiders are likely to be mounted and so need to get their horses and/or camels across).

On the Rhine and the Danube, the defense of the limes, the Roman frontier, included a border wall (earthwork and wood, rather than stone like Hadrian’s wall), similarly supported by legions stationed to the rear, with road networks positioned; once again, the focus is on observing threats, slowing them down and channeling them so that the legions can engage them in the field. This is a system based around observe-channel-respond, rather than an effort to block advances completely.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part II: Romans Playing Cards”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-11-12.

November 27, 2022

The Costliest Day in US Marine History – WW2 – 222 – November 26, 1943

World War Two

Published 26 Nov 2022The Americans attack the Gilbert Islands this week, and though they successfully take Tarawa and Makin Atolls, it is VERY costly in lives, and show that the Japanese are not going to be defeated easily. They also have a naval battle in the Solomons. Fighting continues in the Soviet Union and Italy, and an Allied conference takes place in Cairo, a prelude for a major one in Teheran next week.

(more…)

November 26, 2022

Why so Deadly? – Battle of Okinawa 1945

Real Time History

Published 25 Nov 2022The American invasion of Okinawa was the last big island operation on the Pacific Front. It took the US Marines and Army troops several months to defeat the last Japanese resistance on the island in one of the costliest American victories of the 2nd World War — but in the end not even Japanese Kamikaze attacks and using the civilian population could avert the outcome.

(more…)

November 24, 2022

QotD: Roman legionary fortified camps

The degree to which we should understand the Roman habit of constructing fortified marching camps every night as exceptional is actually itself an interesting question. Our sources disagree on the origins of the Roman fortified camp; Frontinus (Front. Strat 4.1.15) says that the Romans learned it from the Macedonians by way of Pyrrhus of Epirus but Plutarch (Plut. Pyrrhus 16.4) represents it the other way around; Livy, more reliable than either agrees with Frontinus that Pyrrhus is the origin point (Liv. 35.14.8) but also has Philip V, a capable Macedonian commander, stand in awe of Roman camps (Liv. 31.34.8). It’s clear there was something exceptional about the Roman camps because so many of our sources treat it as such (Liv. 31.34.8; Plb. 18.24; Josephus BJ 3.70-98). Certainly the Macedonians regularly fortified their camps (e.g. Plb. 18.24; Liv 32.5.11-13; Arr. Alex. 3.9.1, 4.29.1-3; Curtius 4.12.2-24, 5.5.1) though Carthaginian armies seem to have done this less often (e.g. Plb. 6.42.1-2 encamping on open ground is treated as a bold new strategy).

It is probably not the camps themselves, but their structure which was exceptional. Polybius claims Greeks “shirk the labor of entrenching” (Plb. 6.42.1-2) and notes that the stakes the Romans used to construct the wooden palisade wall of the camp are more densely placed and harder to remove (Plb. 18.18.5-18). The other clear difference Polybius notes is the order of Roman camps, that the Romans lay out their camp the same way wherever it is, whereas Greek and Macedonian practice was to conform the camp to the terrain (Plb. 6.42); the archaeology of Roman camps bears out the former whereas analysis of likely battlefield sites (like the Battle of the Aous) seem to bear out the latter.

In any case, the mostly standard layout of Roman marching camps (which in the event the Romans lay siege, become siege camps) enables us to talk about the Roman marching camp because as far as we can tell they were all quite similar (not merely because Polybius says this, but because the basic features of these camps really do seem to stay more or less constant.

The basic outline of the camp is a large rectangle with the corners rounded off, which has given the camps (and later forts derived from them) their nickname: “playing card” forts. The size and proportions of a fortified camp would depend on the number of legions, allies and auxiliaries present, from nearly square to having one side substantially longer than the other. This isn’t the place to get into the internal configuration of the camp, except to note that these camps seemed to have been standardized so that the layout was familiar to any soldier wherever they went, which must have aided in both building the camp (since issues of layout would become habit quickly) and packing it up again.

Now a fortified camp does not have the same defensive purpose as a walled city: the latter is intended to resist a siege, while a fortified camp is mostly intended to prevent an army from being surprised and to allow it the opportunity to either form for battle or safely refuse battle. That means the defenses are mostly about preventing stealthy approach, slowing down attackers and providing a modest advantage to defenders with a relative economy of cost and effort.

In the Roman case, for a completed defense, the outermost defense was the fossa or ditch; sources differ on the normal width and depth of the ditch (it must have differed based on local security conditions) but as a rule they were at least 3′ and 5′ wide and often significantly more than this (actual measured Roman defensive fossae are generally rather wider, typically with a 2:1 ratio of width to depth, as noted by Kate Gilliver. The earth excavated to make the fossa was then piled inside of it to make a raised earthwork rampart the Romans called the agger. Finally, on top of the agger, the Romans would place the valli (“stakes”) they carried to make the vallum. Vallum gives us our English word “wall” but more nearly means “palisade” or “rampart” (the Latin word for a stone wall is more often murus).

Polybius (18.18) notes that Greek camps often used stakes that hadn’t had the side branches removed and spaced them out a bit (perhaps a foot or so; too closely set for anyone to slip through); this sort of spaced out palisade is a common sort of anti-ambush defense and we know of similar village fortifications in pre- and early post-contact North America on the East coast, used to discourage raids. Obviously the downside is that when such stakes are spaced out, it only takes the removal of a few to generate a breach. The Roman vallum, by contrast, set the valli fixed close together with the branches interlaced and with the tips sharpened, making them difficult to climb or remove quickly.

The gateway obviously could not have the ditch cut across the entryway, so instead a second ditch, the titulum, was dug 60ft or so in front of the gate to prevent direct approach; the gate might also be reinforced with a secondary arc of earthworks, either internally or externally, called the clavicula; the goal of all of this extra protection was again not to prevent a determined attacker from reaching the gates, but rather to slow a surprise attack down to give the defender time to form up and respond.

And that’s what I want to highlight about the nature of the fortified Roman camp: this isn’t a defense meant to outlast a siege, but – as I hinted at last time – a defense meant to withstand a raid. At most a camp might need to withstand the enemy for a day or two, providing the army inside the opportunity to retreat during the night.

We actually have some evidence of similar sort of stake-wall protections in use on the East Coast of Native North America in the 16th century, which featured a circular stake wall with a “baffle gate” that prevented a direct approach and entrance. The warfare style of the region was heavily focused on raids rather than battles or sieges (though the former did happen) in what is sometimes termed the “cutting off way of war” (on this see W. Lee, “The Military Revolution of Native North America” in Empires and Indigines, ed. W. Lee (2011)). Interestingly, this form of Native American fortification seems to have been substantially disrupted by the arrival of steel axes for presumably exactly the reasons that Polybius discusses when thinking about Greek vs. Roman stake walls: pulling up a well-made (read: Roman) stake wall was quite difficult. However, with steel axes (imported from European traders), Native American raiding forces could quickly cut through a basic palisade. Interestingly, in the period that follows, Lee (op. cit.) notes a drift towards some of the same methods of fortification the Romans used: fortifications begin to square off, often combined a ditch with the palisade and eventually incorporated corner bastions projecting out of the wall (a feature Roman camps do not have, but later Roman forts eventually will, as we’ll see).

Roman field camps could be more elaborate than what I’ve described; camps often featured, for instance, observation towers. These would have been made of wood and seem to have chiefly been elevated posts for lookouts rather than firing positions, given that they sit behind the vallum rather than projecting out of it (meaning that it would be very difficult to shoot any enemy who actually made it to the vallum from the tower).

When a Roman army laid siege to a fortified settlement, the camp formed the “base” from which siege works were constructed (particularly circumvallation – making a wall around the enemy’s city to keep them in – and contravallation – making a wall around your siege position to keep other enemies out. We’ll discuss these terms in more depth a little later). Some of the most elaborate such works we have described are Caesar’s fortifications at the Siege of Alesia (52 BC; Caes. B.G. 7.72). There the Roman line consisted of an initial trench well beyond bow-shot range from his planned works in order to prevent the enemy from disrupting his soldiers with sudden attacks, then an agger and vallum constructed with a parapet to allow firing positions from atop the vallum, with observation towers every 80 feet and two ditches directly in front of the agger, making for three defensive ditches in total (be still Roel Konijnendijk‘s heart! – but seriously, the point he makes on those Insider “Expert Rates” videos about the importance of ditches are, as you can tell already, entirely accurate), which were reinforced with sharpened stakes faced outward. As Caesar expressly notes, these weren’t meant to be prohibitive defenses that would withstand any attack – wooden walls can be chopped or burned, after all – but rather to give him time to respond to any effort by the defenders to break out or by attackers to break in (he also contravallates, reproducing all of these defenses facing outward, as well).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part II: Romans Playing Cards”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-11-12.