After the riots were over, the government appointed a commission to enquire into their causes. The members of this commission were appointed by all three major political parties, and it required no great powers of prediction to know what they would find: lack of opportunity, dissatisfaction with the police, bla-bla-bla.

Official enquiries these days do not impress me, certainly not by comparison with those of our Victorian forefathers. No one who reads the Blue Books of Victorian Britain, for example, can fail to be impressed by the sheer intellectual honesty of them, their complete absence of any attempt to disguise an often appalling reality by means of euphemistic language, and their diligence in collecting the most disturbing information. (Marx himself paid tribute to the compilers of these reports.)

I was once asked to join an enquiry myself. It was into an unusual spate of disasters in a hospital. It was clear to me that, although they had all been caused differently, there was an underlying unity to them: they were all caused by the laziness or stupidity of the staff, or both. By the time the report was written, however (and not by me), my findings were so wrapped in opaque verbiage that they were quite invisible. You could have read the report without realising that the staff of the hospital had been lazy and stupid; in fact, the report would have left you none the wiser as to what had actually happened, and therefore what to do to ensure that it never happened again. The purpose of the report was not, as I had naively supposed, to find the truth and express it clearly, but to deflect curiosity and incisive criticism in which it might have resulted if translated into plain language.

Theodore Dalrymple, “It’s a riot”, New English Review, 2012-04.

April 13, 2023

QotD: The real purpose of modern-day official commissions

April 5, 2023

QotD: Harry Flashman’s adventures were not intended as “covert anticolonialism”

In their insistence on judging the value of a work of art principally in terms of its moral qualities, the publishers of today are heirs to a tradition of puritanism going back to Plato. But there has long been an anti-puritanical argument available too, the most notorious of them being the one articulated by Oscar Wilde: that to assess art in moral terms is to commit some sort of category mistake. “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well-written, or badly written. That is all.” But that argument was never very persuasive by itself, and contains a large non sequitur. Why should that be “all”? Why can’t it be that part of what we’re saying in calling a book well-written is that it is morally exemplary? Surely it is those who call on us to leave our moral values at the door who have some explaining to do.

George MacDonald Fraser himself sometimes seemed to take Wilde’s view of the matter. He zealously repudiated, in his non-fiction, all attempts to defend his fiction as covertly anti-colonial, taking great pleasure in mocking critics who “hailed it as a scathing attack on British imperialism”. Was he “taking revenge on the 19th century on behalf of the 20th”? “Waging war on Victorian hypocrisy”? Were the books, as one religious journal was supposed to have claimed, “the work of a sensitive moralist” highly relevant to “the study of ethics”? No, he said, The Flashman Papers were to be taken “at face value, as an adventure story dressed up as the memoirs of an unrepentant old cad”.

Is Fraser’s avowed amoralism the whole story? In one respect, the Flashman books are certainly amoral: they embody no systematic view that colonialism was wrong, illegitimate, unjust. (Nor, come to it, do they embody the view that it was right, legitimate and just.) As Fraser appears to see it in his fiction, empire was simply the default mode of political life in much of the world. This indeed was the case for much of human history. To be colonised was generally a misfortune for the colonised, but the individual coloniser was neither hero nor villain, just a self-interested actor acting on what he believed to be the necessities of his time and place.

We live in a world where we are constantly exercised by the problem of complicity. We wonder: am I complicit in climate change because I just put on the washing machine? In a sufficiently inclusive sense of the word “complicit”, of course I am: one of countless agents whose everyday actions add a tiny bit more carbon to the atmosphere. But outside an ethics seminar, what I’d tell you is that I was just doing my laundry because the clothes were beginning to stink.

Fraser was a deft enough writer to force his characters to confront the larger, what we today might call “structural” questions, in terms that belong to their own times, not to ours. At a pivotal moment in Flash for Freedom, Flashman is enslaved himself in America. Thrown into a cart with a charismatic slave called Cassy, he gets to hear her relish the irony of his position: “Well, now one of you knows what it feels like … Now you know what a filthy race you belong to.” Is there any hope of escape, he asks her desperately. None, she replies, “there isn’t any hope. Where can you run to, in this vile country? This land of freedom! With slave-catchers everywhere, and dogs, and whipping-houses, and laws that say I’m no better than a beast in a sty!” Flashman has the grace to be silent; what can he say?

Nikhil Krishnan, “Harry Flashman’s imperial morality”, UnHerd, 2022-12-26.

March 14, 2023

“Strangely, my friends have a more negative view of the feminist movement than I do”

Bryan Caplan explains why he chooses to write the books he writes:

Almost by definition, writing controversial books tends to provoke negative emotional reactions. Anger above all. Anger which, in turn, inspires fear. And not without just cause; the sad story of Salman Rushdie sends shivers down the spine of almost any writer. If you write controversial books — or care about someone who does — you should be at least a little afraid of the anger your writing inspires.

[…]

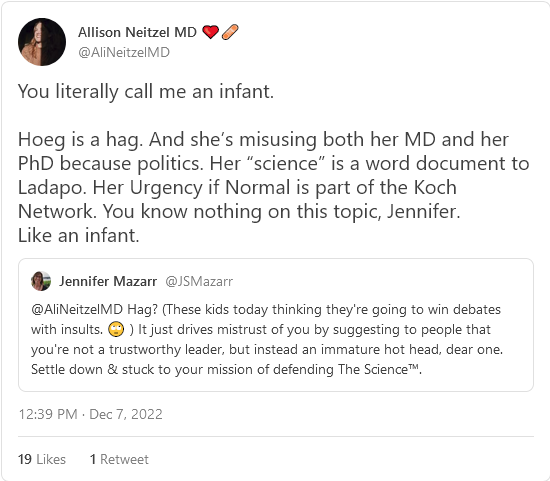

In contrast, when I announced the imminent publication of Don’t Be a Feminist, the fear went through the roof. Several folks warned me of “career suicide”. Others told me that I had no idea what horrors awaited me. Friends staged mini-interventions on my behalf.

The underlying premise, naturally, was that the feminist movement is at once terribly powerful and horribly bad-tempered.

My best guess is that the warnings are overblown. Strangely, my friends have a more negative view of the feminist movement than I do. Whether my guess is right or wrong, though, all this intense, widespread fear really ought to trouble the feminist conscience.

If I said, “Hi” to one of my kids’ friends, and they responded by fleeing in terror, my reaction would be, “Did I do something to scare him?” I would ask my kids, “Why was he so afraid of me?” If such incidents started to repeat, I would be severely troubled. “I thought I came off as a friendly dad, but I guess I’m seen as an ogre.”

The same applies if I were a feminist, and I discovered that critics are literally afraid to criticize feminism. If only a few critics feared feminism, my question would be, “What did we do to scare them?” If I discovered that fear of feminism was widespread, a full soul-search would be in order. “I thought we came off as a friendly movement, but I guess we’re seen as ogres.”

And guess what? Fear of feminism plainly is widespread.

What, then, are feminists doing wrong? Above all, cultivating and expressing vastly too much anger. Sharing your angry feelings is an effective way to dominate the social world, but a terrible way to discover the truth or sincerely convince others. Maybe you don’t mean to scare others; maybe you’re just acting impulsively. Yet either way, the fear feminists inspire is all too real.

March 4, 2023

Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning

In The Critic, Robert Lyman reviews a recent book offering a rather more nuanced view of the British empire:

The book is a careful analysis of empire from an ethical perspective, examining a set of moral questions. This includes whether the British Empire was driven by lust or greed; whether it was racist and condoned, supported or encouraged slavery; whether it was based on the conquest of land; whether it entailed genocide and or economic exploitation; whether its lack of democracy made it illegitimate; and whether it was intrinsically or systemically violent.

Biggar’s proposition is simple: that we look at Britain’s history without assuming the zero-sum position that imperialism and colonialism were inherently bad, that motives and agency need to be considered and that good did flow from bad, as well as bad from good.

Whether he succeeds depends on the reader’s willingness to appreciate these moral or ethical propositions, and to re-evaluate accordingly. In my view, he has mounted a coolly dispassionate defence of his proposition, challenging the hysteria of those who suggest that the British Empire was the apotheosis of evil. Biggar’s calm dissection of these inflated claims allows us to see that they say much more about the motivations, assumptions and political ideologies of those who hold these views than they do about what history presents to us as the realities of a morally imperfect past.

He reminds us that British imperialism had no single wellspring. Most of us can easily dismiss the notion that it was a product of an aggressive, buccaneering state keen to enrich itself at the expense of peoples less able to defend themselves. Equally, it is untrue that economic motives drove all imperialist or colonial endeavour, or that economics (business, trade and commerce) was the primary force sustaining the colonial regimes that followed.

As Biggar asserts, both imperialism and colonialism were driven from different motivations at different times. Each ran different journeys, with different outcomes depending on circumstances. The assertion that there is a single defining imperative for each instance of imperial initiative or colonial endeavour simply does not accord with the facts.

Whilst other issues played a part, it was social, religious and political motives which drove the colonial endeavour in the New World from the 1620s: security and religion drove the subjugation of Catholic (and therefore Royalist) Ireland in the 1650s; social and administrative factors led to the settlement in Australia from 1788; and social and religious imperatives drove the colonisation of New Zealand in the 1840s.

In circumstances where trade and the security of trade was the primary motive for imperialism — think of Clive in the 1750s, for example — a wide variety of outcomes ensued. Some occurred as a natural consequence of imperialism. In India, Clive’s defeat of the Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah in 1757 was in support of a palace coup that put Siraj’s uncle Mir Jafar on the throne of Bengal, thus allowing the East India Company the favoured trading status that Siraj had previously rejected.

This led in time to the Company taking over the administrative functions of the Bengal state (zamindars collected both rents for themselves and taxes for the government). Seeking to protect its new prerogatives, it provided security from both internal (civil disorder and lawlessness) and external threats (the Mahratta raiders, for example). The incremental, almost accidental, accrual of power that began in the early 1600s stepped into colonial administration 150 years later, leading to the transfer of power across a swathe of the sub-continent to the British Crown in 1858.

Biggar’s argument is that, running in parallel with this expansion came a host of other consequences, not all of which can be judged “bad”. We may not like what prompted the colonial enterprise at the outset (not all of which was morally contentious, such as the need to trade), but we cannot deny that good things, as well as bad, followed thereafter.

February 25, 2023

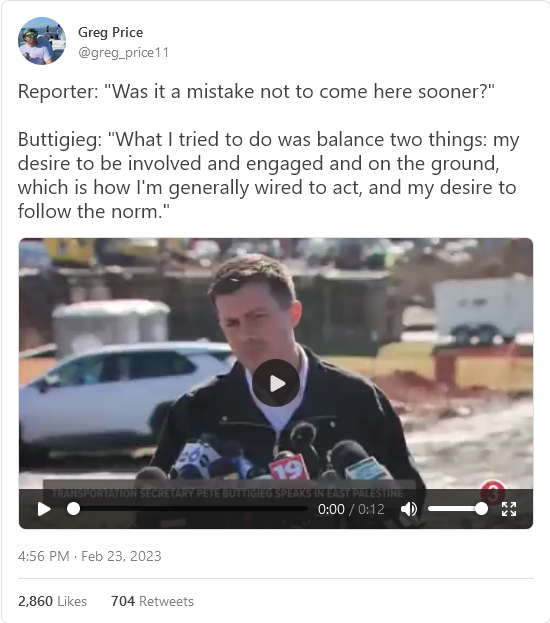

Buttigieg isn’t covering himself in glory over his belated East Palestine train derailment response

Jim Treacher is clearly trying to at least pretend some sympathy for Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, but it’s a tough assignment:

Pete Buttigieg is the type of guy who walks into a job interview and says his biggest weakness is his perfectionism. As a kid he always had an apple for the teacher, and if she forgot to assign homework that day, he was the first with his hand up. He’s a repulsive little hall monitor, so all the other repulsive little hall monitors think he’s simply divine.

Mayor Pete and his fan club are having a really bad time right now, because for once he’s expected to actually do something. Producing results simply isn’t his specialty. After spending three weeks hoping the East Palestine, Ohio rail disaster would stop bothering him if he just ignored it, he finally showed up there yesterday.

And I’m starting to understand his reluctance:

What a visual, huh? He looks like a little kid playing Bob the Builder. It’s not quite Dukakis in the tank, but it’s close.

And then it got worse: He started talking.

He’s just so gosh-darn dedicated to his job, you see. His only mistake was listening to you people. He followed the norm. This is your fault!

And then he blurted out this instant classic:

Now, which of those words should you try to avoid when you’re talking about a disastrous train derailment? I’m starting to suspect this guy isn’t the unparalleled megagenius the libs keep telling us he is.

[…]

Team Pete is more concerned about reporters asking about East Palestine than about the disaster itself. The rest of us are just an abstraction to them. If they accidentally manage to help some of us, that’s fine. If not, that’s also fine. Either way, we cannot be allowed to stand in the way of their political aspirations.

Mayor Pete really did think this gig would be a cinch, didn’t he? Like, he could just do all the reading the night before the final and ace it. He’s positively resentful at being expected to do what we’re paying him to do. He thinks he’s too good for this job, which is why he’s very bad at this job.

Will Buttigieg’s tenure as transportation secretary ruin his presidential prospects? After all, that’s what this is all about for him. Maybe, maybe not. It’s not as if politics is about solving problems. All you have to do is claim you solved the problems, and your team will cheer for you no matter what.

February 21, 2023

Larry Correia’s In Defense of the Second Amendment

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, Charles Curley reviews Larry Correia’s latest non-fiction book:

The name Larry Correia may ring a bell for Libertarian Enterprise readers. He has written fiction since 2008. He started with Monster Hunter, a self-published novel that later got a contract from Baen Books. He has since become a New York Times best selling author, and a finalist for the John Campbell award.

He also originated the Sad Puppies campaign, an effort to turn the Hugos away from their politically correct drift.

Yeah, guns and science fiction. TLE readers should appreciate that combination.

First off, this is not a scholarly exercise, nor does it break much new ground in the gun control arena. If you want scholarly language, look elsewhere, to, say, Don Kates, Stephen Halbrook, or David Kopel: in places this book is more of a rant than a treatise. So if you enjoy the snark of L. Neil Smith or H. L. Mencken, you’ll like this book. None the less, it has 12 pages of end notes and five pages of index. (But, oddly enough, no table of contents.)

Correia says so: “This book isn’t intended for policy wonks and pundits. I’m not an academic. I’m not a statistician. I’m a writer who knows a lot about guns.” (p. 23) And he’s tired of hearing the same tired old stuff trotted out again and again in any discussion about gun control. This book is his reply. “I won’t lie, I’d like this book to give ammo to the people on my side of the debate. To those of you who are on the fence, undecided, I want to help you understand more about how crime and gun control laws actually work.” (p. 23)

Chapter One is entitled Guns and Vultures. The vultures are the people who feed on every tragedy, trying to fit it into their agenda of more gun control and more dependence on the state. The people who heed Rahm Emmanuel’s famous dictum: “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.” The people who wring their hands and say, we have to do something! even when the something has been tried before and found wanting, or even found impossible.

Much of the book is devoted to refuting the anti-gun arguments. I trust I needn’t outline those to TLE readers.

Note that while he’s confident that the book is well worth reading, he hasn’t actually read any of Larry’s fiction writing, so he can’t be dismissed as a fan who’d automatically recommend the book.

February 15, 2023

Refuting The End of History and the Last Man

Freddie deBoer responds to a recent commentary defending the thesis of Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man:

… Ned Resnikoff critiques a recent podcast by Hobbes and defends Francis Fukuyama’s concept of “the end of history”. In another case of strange bedfellows, the liberal Resnikoff echoes conservative Richard Hanania in his defense of Fukuyama — echoes not merely in the fact that he defends Fukuyama too, but in many of the specific terms and arguments of Hanania’s defense. And both make the same essential mistake, failing to understand the merciless advance of history and how it ceaselessly grinds up humanity’s feeble attempts at macrohistoric understanding. And, yes, to answer Resnikoff’s complaint, I’ve read the book, though it’s been a long time.

The big problem with The End of History and the Last Man is that history is long, and changes to the human condition are so extreme that the terms we come up with to define that condition are inevitably too contextual and limited to survive the passage of time. We’re forever foolishly deciding that our current condition is the way things will always be. For 300,000 years human beings existed as hunter-gatherers, a vastly longer period of time than we’ve had agriculture and civilization. Indeed, if aliens were to take stock of the basic truth of the human condition, they would likely define us as much by that hunter-gatherer past as our technological present; after all, that was our reality for far longer. Either way – those hunter-gatherers would have assumed that their system wasn’t going to change, couldn’t comprehend it changing, didn’t see it as a system at all, and for 3000 centuries, they would have been right. But things changed.

And for thousands of years, people living at the height of human civilization thought that there was no such thing as an economy without slavery; it’s not just that they had a moral defense of slavery, it’s that they literally could not conceive of the daily functioning of society without slavery. But things changed. For most humans for most of modern history, the idea of dynastic rule and hereditary aristocracy was so intrinsic and universal that few could imagine an alternative. But things changed. And for hundreds of years, people living under feudalism could not conceive of an economy that was not fundamentally based on the division between lord and serf, and in fact typically talked about that arrangement as being literally ordained by God. But things changed. For most of human history, almost no one questioned the inherent and unalterable second-class status of women. Civilization is maybe 12,000 years old; while there’s proto-feminist ideas to be found throughout history, the first wave of organized feminism is generally defined as only a couple hundred years old. It took so long because most saw the subordination of women as a reflection of inherent biological reality. But women lead countries now. You see, things change.

And what Fukuyama and Resnikoff and Hanania etc are telling you is that they’re so wise that they know that “but then things changed” can never happen again. Not at the level of the abstract social system. They have pierced the veil and see a real permanence where humans of the past only ever saw a false one. I find this … unlikely. Resnikoff writes “Maybe you think post-liberalism is coming; it just has yet to be born. I guess that’s possible.” Possible? The entire sweep of human experience tells us that change isn’t just possible, it’s inevitable; not just change at the level of details, but changes to the basic fabric of the system.

The fact of the matter is that, at some point in the future, human life will be so different from what it’s like now, terms like liberal democracy will have no meaning. In 200 years, human beings might be fitted with cybernetic implants in utero by robots and jacked into a virtual reality that we live in permanently, while artificial intelligence takes care of managing the material world. In that virtual reality we experience only a variety of pleasures that are produced through direct stimulation of the nervous system. There is no interaction with other human beings as traditionally conceived. What sense would the term “liberal democracy” even make under those conditions? There are scientifically-plausible futures that completely undermine our basic sense of what it means to operate as human beings. Is one of those worlds going to emerge? I don’t know! But then, Fukuyama doesn’t know either, and yet one of us is making claims of immense certainty about the future of humanity. And for the record, after the future that we can’t imagine comes an even more distant future we can’t conceive of.

People tend to say, but the future you describe is so fanciful, so far off. To which I say, first, human technological change over the last two hundred years dwarfs that of the previous two thousand, so maybe it’s not so far off, and second, this is what you invite when you discuss the teleological endpoint of human progress! You started the conversation! If you define your project as concerning the final evolution of human social systems, you necessarily include the far future and its immense possibilities. Resnikoff says, “the label ‘post-liberalism’ is something of an intellectual IOU” and offers similar complaints that no one’s yet defined what a post-liberal order would look like. But from the standpoint of history, this is a strange criticism. An 11th-century Andalusian shepherd had no conception of liberal democracy, and yet here we are in the 21st century, talking about liberal democracy as “the object of history”. How could his limited understanding of the future constrain the enormous breadth of human possibility? How could ours? To buy “the end of history”, you have to believe that we are now at a place where we can accurately predict the future where millennia of human thinkers could not. And it’s hard to see that as anything other than a kind of chauvinism, arrogance.

Fukuyama and “the end of history” are contingent products of a moment, blips in history, just like me. That’s all any of us gets to be, blips. The challenge is to have humility enough to recognize ourselves as blips. The alternative is acts of historical chauvinism like The End of History.

February 1, 2023

It’s the job of the music critic to be loudly and confidently wrong as often as possible

Ted Gioia points out that a lot of musical criticism does not pass the test of time … and sometimes it’s shown to be wrong before the ink is dry:

When I was in my twenties, I embarked on writing an in-depth history of West Coast jazz. At that juncture in my life, it was the biggest project I’d ever tackled. Just gathering the research materials took several years.

There was no Internet back then, and so I had to spend weeks and months in various libraries going through old newspapers and magazines — sometimes on microfilm (a cursed format I hope has disappeared from the face of the earth), and occasionally with physical copies.

At one juncture, I went page-by-page through hundreds of old issues of Downbeat magazine, the leading American jazz periodical founded back in 1934. And I couldn’t believe what I was reading. Again and again, the most important jazz recordings — cherished classics nowadays — were savagely attacked or smugly dismissed at the time of their initial release.

The opinions not only were wrong-headed, but they repeatedly served up exactly the opposite opinion of posterity.

Back in my twenties, I was dumbfounded by this.

I considered music critics as experts, and hoped to learn from them. But now I saw how often they got things wrong — and not just by a wee bit. They were completely off the mark.

Nowadays, this doesn’t surprise me at all. I’m painfully aware of all the compromised agendas at work in reviews — writers trying to please an editor, or impress other critics, or take a fashionable pose, or curry favor with the tenure committee, or whatever. But there is also something deeper at play in these huge historical mistakes in critical judgments, and I want to get to the bottom of it.

Let’s consider the case of the Beatles.

On the 50th anniversary of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the New York Times bravely reprinted the original review that ran in the newspaper on June 18, 1967. I commend the courage of the decision-makers who were willing to make Gray Lady look so silly. But it was a wise move — if only because readers deserve a reminder of how wrong critics can be.

“Like an over-attended child, ‘Sergeant Pepper’ is spoiled,” critic Richard Goldstein announced. And he had a long list of complaints. The album was just a pastiche, and “reeks of horns and harps, harmonica quartets, assorted animal noises and a 91-piece orchestra”. He mocks the lyrics as “dismal and dull”. Above all the album fails due to an “obsession with production, coupled with a surprising shoddiness in composition”. This flaw doesn’t just destroy the occasional song, but “permeates the entire album”.

Goldstein has many other criticisms — he gripes about dissonance, reverb, echo, electronic meandering, etc. He concludes by branding the entire record as an “undistinguished collection of work”, and even attacks the famous Sgt. Pepper’s cover — lauded today as one of the most creative album designs of all time — as “busy, hip, and cluttered”.

The bottom line, according to the newspaper of record: “There is nothing beautiful on ‘Sergeant Pepper’. Nothing is real and there is nothing to get hung about.”

How could he get it so wrong?

January 16, 2023

Paul Johnson on Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The book Paul Johnson may best be known for is Intellectuals, an essay collection highly critical of many of the “great men” of intellectual history. Birth of the Modern, the first Johnson book I read, was also skeptical of the bright lights of European intellectualism, but Intellectuals is where he concentrated on the biographical details of many of them. Ed West selected some of Johnson’s essay on Jean-Jacques Rousseau as part of his obituary post:

… Johnson is best known to many for his history books, one of the most entertaining being Intellectuals. Published in 1989 and structured as a series of – very critical – biographies of great philosophers, poets, playwrights and novelists, Johnson’s book got to the essence of the intellectual mindset in all its worst aspects: their intense selfishness and narcissism, their callousness towards friends and lovers, and their fondness for giving moral support to some of the worst ideas and regimes in history.

One of the most prominent Catholics in British journalism, Johnson saw secular intellectuals as modern successors to the theologians of the medieval Church, the difference being that, without the restraints of religious institutions, their egotism was uncontrolled.

Writers and artists are often incredibly selfish people, and this is true across the political spectrum, but of course it’s far more satisfying to read about those men who claimed to be the saviour of the poor and humble yet were so relentlessly horrible to actual people around them. That’s what makes the book – published just as the system imagined by one of its subjects came crashing down in eastern Europe – so satisfying.

One of the targets, er, I mean “subjects” of Intellectuals was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was quite the piece of work indeed:

It begins with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the “first of the modern intellectuals” and perhaps the subject of Johnson’s most intense vitriol.

“Older men like Voltaire had started the work of demolishing the altars and enthroning reason,” he wrote: “But Rousseau was the first to combine all the salient characteristics of the modern Promethean: the assertion of his right to reject the existing order in its entirety; confidence in his capacity to refashion it from the bottom in accordance with principles of his own devising belief that this could be achieved by the political process; and, not least, recognition of the huge part instinct, intuition and impulse play in human conduct.

“He believed he had a unique love for humanity and had been endowed with unprecedented gifts and insights to increase its felicity.” He was also an appalling human being.

[…]

Madame Louise d’Épinay, a lover who he treated terribly, said “I still feel moved by the simple and original way in which he recounted his misfortunes”. Another mistress, Madame de Warens, effectively supported him in hard times but, when she fell into destitution, he did nothing to prevent her dying of malnutrition.

Rousseau had a “pseudo-wedding” with his mistress Therese Levasseur where he gave a speech about himself, saying there would be statues erected to him one day and “it will then be no empty honour to have been a friend of Jean-Jacques Rousseau”. He later accused her brother of stealing his 42 fine shirts and when he had guests for dinner she was not allowed to sit down. He praised her as “a simple girl without flirtatiousness”, “timorous and easily dominated”.This easily-dominated woman gave birth to five of his children, whom he had sent to an orphanage where two-thirds of babies died within the first year and just one in 20 reached adulthood, usually becoming beggars. He made almost no attempt to ever track them down, and said having children was “an inconvenience”.

“How could I achieve the tranquillity of mind necessary for my work, my garret filled with domestic cares and the noise of children?” He would have been forced to do degrading work “to all those infamous acts which fill me with such justified horror”.

He was spared that horror and instead given time to develop his ideas, which were fashionable, attractive and completely unworkable. “The fruits of the earth belong to us all, the earth itself to none”, he said, and hoped that “the rich and the privileged would be replaced by the state which reflected the general will”.

What would this mean in practice? “The people making laws for itself cannot be unjust … The general will is always righteous”.

Despite his ideas veering between woeful naivety and sinister authoritarianism, they proved hugely popular, especially with the men and women who in 1789, just a decade after his death, would bring France’s old regime crashing down — with horrific consequences. As Thomas Carlyle famously said of Rousseau’s The Social Contract: “The second edition was bound in the skins of those who had laughed at the first.”

Rousseau was perhaps the most influential figure of the modern era. In particular his rejection of original sin would become far more popular in the late 20th century; indeed it is at the core of what we call the culture war, and its fundamental conflict over human nature.

QotD: The avant-garde

There is no more evanescent quality than modernity, a rather obvious or even banal observation whose import those who take pride in their own modernity nevertheless contrive to ignore. Having reached the pinnacle of human achievement by living in the present rather than in the past, they assume that nothing will change after them; and they also assume that the latest is the best. It is difficult to think of a shallower outlook.

Of course, in certain fields the latest is inclined to be best. For example, no one would wish to be treated surgically using the methods of Sir Astley Cooper: but if we want modern treatment, it is not because it is modern but because it better as gauged by pretty obvious criteria. If it were worse (as very occasionally it is), we should not want it, however modern it were.

Alas, the idea of progress has infected important spheres in which it has no proper application, particularly the arts. It is difficult to overestimate the damage that the gimcrack notion of teleology inhering in artistic endeavour has inflicted on all the arts, exemplified by the use of the term avant-garde: as if artists were, or ought to be, soldiers marching in unison to a predetermined destination. If I had the power to expunge a single expression from the vocabulary art criticism, it would be avant-garde.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Architectural Dystopia: A Book Review”, New English Review, 2018-10-04.

December 12, 2022

The British Empire(s)

At Spiked, James Heartfield discusses the changing attitudes toward British imperial history:

Renewed interest in the history of the British Empire has generated a great amount of fascinating research and reflection. Over the past decade or more, there have been many books written about the empire – popular, academic, polemical and picaresque. There has been Akala’s Natives, William Dalrymple’s The Anarchy, Shashi Tharoor’s Inglorious Empire and Caroline Elkins’ Legacy of Violence, to name just a few.

Today’s approach to the British Empire is invariably critical – often stridently so. It marks a change to the attitude widely held half a century ago, when books on the empire tended to be elegiac farewells, like Paul Scott’s novel, The Jewel in the Crown, or Jan Morris’s Pax Britannica. Today’s critical approach to the empire is certainly a far cry from that which prevailed for a brief moment around the time that Margaret Thatcher was taking back the Falkland Islands. Back then, there was even an attempt at the moral rehabilitation of the empire.

[…]

But there are downsides to the self-excoriating criticism of Britain’s past. Often this approach to history turns into a debilitating exercise in self-loathing, an act of guilt-mongering. Many others have pointed out the limitations of this kind of morbid raking over the coals. But what is just as worrying is that the more we posture over Britain’s colonial past, the less we seem to understand it.

The moralistic framework in which we teach and discuss colonial history reduces our understanding to a single note of complaint. Hence, many historians today now write as if they have to make a case against the empire. This is just kicking at an open door. The empire has very few champions today. And the great British public is certainly not nostalgic for its return, despite some commentators arguing otherwise. Indeed, an ever growing majority think that the empire was a bad thing.

There is another problem with this approach to Britain’s colonial past. It situates readers outside of history. It encourages them to adopt a moralistic rather than historical approach to colonialism. They can do little more than judge the empire as evil. And in doing so, it flattens out the different periods of the colonial project into one long uniform timeline of subjugation. Collapsing distinct periods and stages together leads to a great confusion. For instance, in many accounts, there appears to be little difference between 18th-century British colonialism, which was dominated by slave trading, and the British colonialism of the late 19th century, which was marked by anti-slavery. It is important not to reduce the long history of the empire to a single motivating cause, be it the “English genius” of earlier celebratory accounts or today’s contention that it was all driven by “white supremacy”.

I seek to address these problems in my new book, Britain’s Empires: A History, 1600-2020. There I draw out the differences between the distinctive stages of Britain’s colonial history.

To do this, it is necessary to step back from moral judgement, which foregrounds our attitudes today, in order to try to understand what motivated people back then. That often means looking at a society’s changing social and economic organisation. Britain’s Empires is a history of the empire that holds on to a sense of historical change, and tries to understand the interrelation of its component parts.

The distinct eras of British colonialism are: the Old Colonialism (1600 to 1776); the Empire of Free Trade (1776-1870); the New Colonialism (1870-1945); and the period of decolonisation during the Cold War era (1946-1989). Britain’s Empires ends with an account of the “humanitarian imperialism” of the 1990s up until the present day. This periodisation aims to reflect the objective moments of transition.

December 8, 2022

November 30, 2022

James Gillray

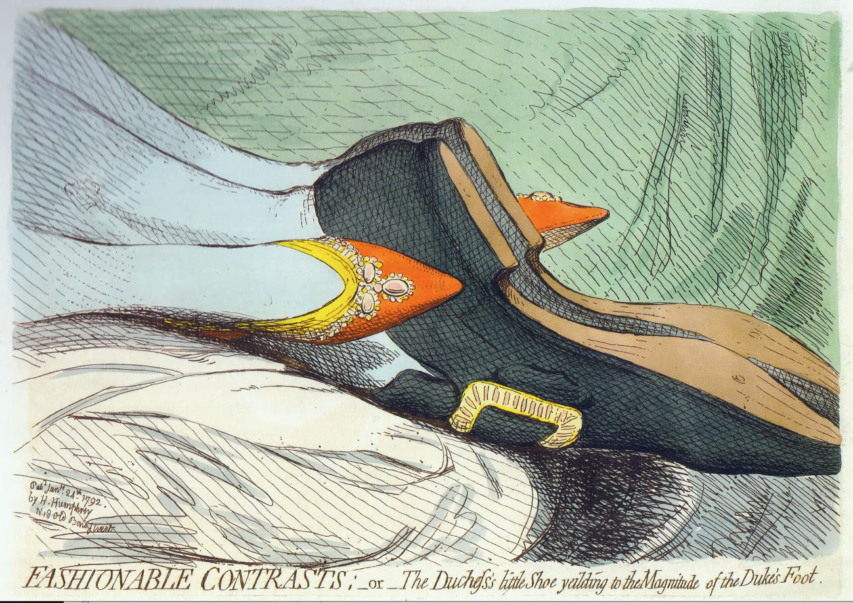

In The Critic, James Stephens Curl reviews a new biography of the cartoonist and satirist James Gillray (1756-1815), who took great delight in skewering the political leaders of the day and pretty much any other target he fancied from before the French Revolution through the Napoleonic wars:

During the 1780s Gillray emerged as a caricaturist, despite the fact that this was regarded as a dangerous activity, rendering an artist more feared than esteemed, and frequently landing practitioners into trouble with the law. Gillray began to excel in invention, parody, satire, fantasy, burlesque, and even occasional forays into pornography. His targets were the great and good, not excepting royalty. But his vision is often dark, his wit frequently cruel and even shockingly bawdy: some of his own contemporaries found his work repellent. He went for politicians: the Whigs Charles James Fox (1749-1806), Edmund Burke (1729-97), and Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (1751-1816) on the one hand, and William Pitt (1759-1806) on the other. Fox was a devious demagogue (“Black Charlie” to Gillray); Burke a bespectacled Jesuit; and Sheridan a red-nosed sot. But Gillray reserved much of his venom for “Pitt the Bottomless”, “an excrescence … a fungus … a toadstool on a dunghill”, and frequently alluded to a lack of masculinity in the statesman, who preferred to company of young men to any intimacies with women, although the caricaturist’s attitude softened to some extent as the wars with the French went on.

As the son of a soldier who had been partly disabled fighting the French, Gillray’s depictions of the excesses of the Revolution were ferocious: one, A Representation of the horrid Barbarities practised upon the Nuns by the Fish-women, on breaking into the Nunneries in France (1792), was intended as a warning to “the FAIR SEX of GREAT BRITAIN” as to what might befall them if the nation succumbed to revolutionary blandishments. The drawing featured many roseate bottoms that had been energetically birched by the fishwives. He also found much to lampoon in his depictions of the Corsican upstart, Napoléon.

[…]

Some of Gillray’s works would pass most people by today, thanks to the much-trumpeted “world-class edication” which is nothing of the sort: one of my own favourites is his FASHIONABLE CONTRASTS;—or—The Duchefs’s little Shoe yeilding to the Magnitude of the Duke’s Foot (1792), which refers to the remarkably small hooves of Princess Frederica Charlotte Ulrica Catherina of Prussia (1767-1820), who married Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763-1827) in 1791: their supposed marital consummation is suggested by Gillray’s slightly indelicate rendering, in which the Duke’s very large footwear dwarfs the delicate slippers of the Duchess.

“In 1791 and 1792, there was no one who received more attention in the British press than Frederica Charlotte, the oldest daughter of the King of Prussia, whose marriage to the second (and favorite) son of King George and Queen Charlotte, Prince Frederick, the Duke of York set off a media frenzy that can only be compared to that of Princess Diana in our own day.”

Description from james-gillray.org/fashionable.htmlAll that said, this is a fine book, beautifully and pithily written, scholarly, well-observed, and superbly illustrated, much in colour. However, it is a very large tome (290 x 248 mm), and extremely heavy, so can only be read with comfort on a table or lectern. The captions give the bare minimum of information, and it would have been far better to have had extended descriptive captions under each illustration, rather than having to root about in the text, mellifluous though that undoubtedly is.

What is perhaps the most important aspect of the book is to reveal Gillray’s significance as a propagandist in time of war, for the images he produced concerning the excesses of what had occurred in France helped to stiffen national resolve to resist the revolutionaries and defeat them and their successor, Napoléon, whose own model for a new Europe was in itself profoundly revolutionary. What he would have made of the present gang of British politicians must remain agreeable speculation.

November 22, 2022

November 16, 2022

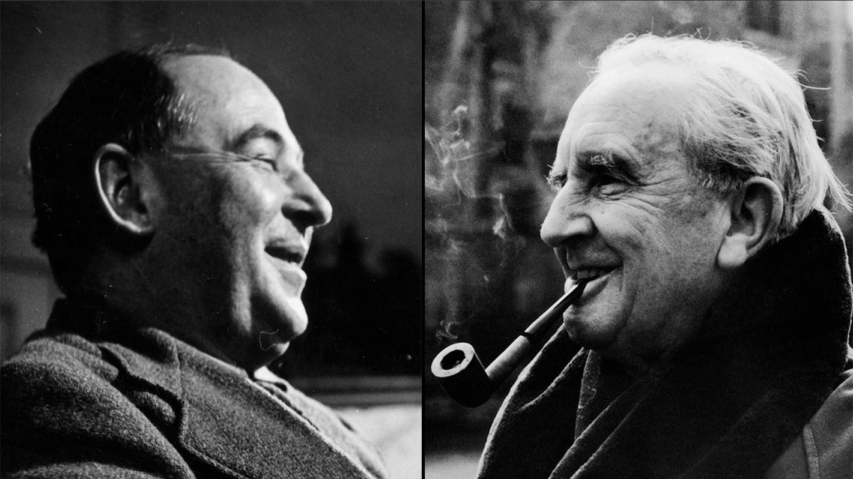

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien … arch-dystopians?

In The Upheaval, N.S. Lyons considers the literary warnings of well-known dystopian writers like Aldous Huxley and George Orwell, but makes the strong case that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien were even more prescient in the warnings their works contain:

Which dystopian writer saw it all coming? Of all the famous authors of the 20th century who crafted worlds meant as warnings, who has proved most prophetic about the afflictions of the 21st? George Orwell? Aldous Huxley? Kurt Vonnegut? Ray Bradbury? Each of these, among others, have proved far too disturbingly prescient about many aspects of our present, as far as I’m concerned. But it could be that none of them were quite as far-sighted as the fairytale spinners.

C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, fast friends and fellow members of the Inklings – the famous club of pioneering fantasy writers at Oxford in the 1930s and 40s – are not typically thought of as “dystopian” authors. They certainly never claimed the title. After all, they wrote tales of fantastical adventure, heroism, and mythology that have delighted children and adults ever since, not prophecies of boots stamping on human faces forever. And yet, their stories and non-fiction essays contain warnings that might have struck more surely to the heart of our emerging 21st century dystopia than any other.

The disenchantment and demoralization of a world produced by the foolishly blinkered “debunkers” of the intelligentsia; the catastrophic corruption of genuine education; the inevitable collapse of dominating ideologies of pure materialist rationalism and progress into pure subjectivity and nihilism; the inherent connection between the loss of any objective value and the emergence of a perverse techno-state obsessively seeking first total control over humanity and then in the end the final abolition of humanity itself … Tolkien and Lewis foresaw all of the darkest winds that now gather in growing intensity today.

But ultimately the shared strength of both authors may have also been something even more straightforward: a willingness to speak plainly and openly about the existence and nature of evil. Mankind, they saw, could not resist opening the door to the dark, even with the best of intentions. And so they offered up a way to resist it.

Subjectivism’s Insidious Seeds

The practical result of education in the spirit of The Green Book must be the destruction of the society which accepts it.

When Lewis delivered this line in a series of February 1943 lectures that would later be published as his short book The Abolition of Man, it must have sounded rather ridiculous. Britain was literally in a war for its survival, its cities being bombed and its soldiers killed in a great struggle with Hitler’s Germany, and Lewis was trying to sound the air-raid siren over an education textbook.

But Lewis was urgent about the danger coming down the road, a menace he saw as just as threatening as Nazism, and in fact deeply intertwined with it, give that:

The process which, if not checked, will abolish Man goes on apace among Communists and Democrats no less than among Fascists. The methods may (at first) differ in brutality. But many a mild-eyed scientists in pince-nez, many a popular dramatist, many an amateur philosopher in our midst, means in the long run just the same as the Nazi rulers of Germany. Traditional values are to be “debunked” and mankind to be cut into some fresh shape at will (which must, by hypothesis, be an arbitrary will) of some few lucky people …

Unfortunately, as Lewis would later lament, Abolition was “almost totally ignored by the public” at the time. But now that our society seems to be truly well along in the process of self-destruction kicked off by “education in the spirit of The Green Book“, it might be about time we all grasped what he was trying to warn us about.

This “Green Book” that Lewis viewed as such a symbol of menace was his polite pseudonym for a fashionable contemporary English textbook actually titled The Control of Language. This textbook was itself a popularization for children of the trendy new post-modern philosophy of Logical Positivism, as advanced in another book, I.A. Richards’ Principles of Literary Criticism. Logical Positivism saw itself as championing purely objective scientific knowledge, and was determined to prove that all metaphysical priors were not only false but wholly meaningless. In truth, however, it was as Lewis quickly realized actually a philosophy of pure subjectivism – and thus, as we shall see, a sure path straight out into “the complete void”.

In Abolition, Lewis zeros in on one seemingly innocuous passage in The Control of Language to begin illustrating this point. It relates a story told by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in which two tourists visit a majestic waterfall. Gazing upon it, one calls it “sublime”. The other says, “Yes, it is pretty.” Coleridge is disgusted by the latter. But, as Lewis recounts, of this story the authors of the textbook merely conclude:

When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall … Actually … he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “sublime”, or shortly, I have sublime feelings … This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.

For Lewis, this “momentous little paragraph” contains all the seeds necessary for the destruction of humanity.