You swear an oath because your own word isn’t good enough, either because no one trusts you, or because the matter is so serious that the extra assurance is required.

That assurance comes from the presumption that the oath will be enforced by the divine third party. The god is called – literally – to witness the oath and to lay down the appropriate curses if the oath is violated. Knowing that horrible divine punishment awaits forswearing, the oath-taker, it is assumed, is less likely to make the oath. Interestingly, in the literature of classical antiquity, it was also fairly common for the gods to prevent the swearing of false oaths – characters would find themselves incapable of pronouncing the words or swearing the oath properly.

And that brings us to a second, crucial point – these are legalistic proceedings, in the sense that getting the details right matters a great deal. The god is going to enforce the oath based on its exact wording (what you said, not what you meant to say!), so the exact wording must be correct. It was very, very common to add that oaths were sworn “without guile or deceit” or some such formulation, precisely to head off this potential trick (this is also, interestingly, true of ancient votives – a Roman or a Greek really could try to bargain with a god, “I’ll give X if you give Y, but only if I get by Z date, in ABC form.” – but that’s vows, and we’re talking oaths).

Thus for instance, runs an oath of homage from the Chronicle of the Death of Charles the Good from 1127:

“I promise on my faith that I will in future be faithful to count William, and will observe my homage to him completely against all persons in good faith and without deceit.”

Not all oaths are made in full, with the entire formal structure, of course. Short forms are made. In Greek, it was common to transform a statement into an oath by adding something like τὸν Δία (by Zeus!). Those sorts of phrases could serve to make a compact oath – e.g. μὰ τὸν Δία! (yes, [I swear] by Zeus!) as an answer to the question is essentially swearing to the answer – grammatically speaking, the verb of swearing is necessary, but left implied. We do the same thing, (“I’ll get up this hill, by God!”). And, I should note, exactly like in English, these forms became standard exclamations, as in Latin comedy, this is often hercule! (by Hercules!), edepol! (by Pollux!) or ecastor! (By Castor! – oddly only used by women). One wonders in these cases if Plautus chooses semi-divine heroes rather than full on gods to lessen the intensity of the exclamation (“shoot!” rather than “shit!” as it were). Aristophanes, writing in Greek, has no such compunction, and uses “by Zeus!” quite a bit, often quite frivolously.

Nevertheless, serious oaths are generally made in full, often in quite specific and formal language. Remember that an oath is essentially a contract, cosigned by a god – when you are dealing with that kind of power, you absolutely want to be sure you have dotted all of the “i”‘s and crossed all of the “t”‘s. Most pre-modern religions are very concerned with what we sometimes call “orthopraxy” (“right practice” – compare orthodoxy, “right doctrine”). Intent doesn’t matter nearly as much as getting the exact form or the ritual precisely correct (for comparison, ancient paganisms tend to care almost exclusively about orthopraxy, whereas medieval Christianity balances concern between orthodoxy and orthopraxy (but with orthodoxy being the more important)).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Oaths! How do they Work?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-28.

January 26, 2024

QotD: How an oath worked in pre-modern cultures

January 13, 2024

History RE-Summarized: The Byzantine Empire

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 29 Sept 2023The Byzantines (Blue’s Version) – a project that took an almost unfathomable amount of work and a catastrophic 120+ individual maps. I couldn’t be happier.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

“Byzantium” I, II, and III by John Julius Norwich, The Byzantine Republic: People and Power in New Rome by Anthony Kaldellis, The Alexiad by Anna Komnene, Osman’s Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire by Caroline Finkel, Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History by John Julius Norwich, A History of Venice by John Julius Norwich. I also have a degree in classical civilization.Additionally, the most august of thanks to our the members of our discord community who kindly assisted me with so much fantastic supplemental information for the scripting and revision process: Jonny, Catia, and Chehrazad. Thank you for reading my nonsense, providing more details to add to my nonsense, and making this the best nonsense it can be.

(more…)

December 31, 2023

Justinian I

In The Critic, George Woudhuysen reviews Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint, by Peter Sarris:

The emperor Justinian did not sleep. So concerned was he for the welfare of his empire, so unremitting was the tide of business, so deep was his need for control that there simply was not time for rest. All this he explained to his subjects in the laws that poured forth constantly from his government — as many as five in a single day; long, complex and involved texts in which the emperor took a close personal interest.

The pace of work for those who served Justinian must have been punishing, and it is perhaps unsurprising that he found few admirers amongst his civil servants. They traded dark hints about the hidden wellsprings of the emperor’s energy. One who had been with him late at night swore that as the emperor paced up and down, his head had seemed to vanish from his body. Another was convinced that Justinian’s face had become a mass of shapeless flesh, devoid of features. That was no human emperor in the palace on the banks of the Bosphorus, but a demon in purple and gold.

There is something uncanny about the story of Justinian, ruler of the eastern Roman Empire from 527 to 565. Born into rural poverty in the Balkans in the late 5th century, he came to prominence through the influence of his uncle Justin. A country boy made good as a guards officer, he became emperor almost by accident in 518. Justinian soon became the mainstay of the new regime and, when Justin died in 527, he was his obvious and preordained successor. The new emperor immediately showed his characteristically frenetic pace of activity, working in consort with his wife Theodora, a former actress of controversial reputation but real ability.

A flurry of diplomatic and military action put the empire’s neighbours on notice, whilst at home there was a barrage of reforming legislation. More ambitious than this, the emperor set out to codify not only the vast mass of Roman law, but also the hitherto utterly untamed opinions of Roman jurists — endeavours completed in implausibly little time that still undergird the legal systems of much of the world.

All the while, Justinian worked ceaselessly to bring unity to a Church fissured by deep theological divisions. After getting the best of Persia — Rome’s great rival — in a limited war on the eastern frontier, Justinian shrewdly signed an “endless peace” with the Sasanian emperor Khusro II in 532. The price — gold, in quantity — was steep, but worthwhile because it freed up resources and attention for more profitable ventures elsewhere.

In that same year, what was either a bout of serious urban disorder that became an attempted coup, or an attempted coup that led to rioting, came within an ace of overthrowing Justinian and levelled much of Constantinople. Other emperors might have been somewhat put off their stride, but not Justinian. The reform programme was intensified, with a severe crackdown on corruption and a wholesale attempt to rewire the machinery of government.

Constantinople was rebuilt on a grander scale, the church of Hagia Sophia being the most spectacular addition, a building that seems still to almost defy the laws of physics. At the same time, Justinian dispatched armies to recover regions lost to barbarian rulers as the western Roman Empire collapsed in the course of the 5th century. In brilliant and daring campaigns, the great general Belisarius conquered first the Vandal kingdom in North Africa (533–34) and then the much more formidable Ostrogothic realm in Italy (535–40), with armies that must have seemed almost insultingly small to the defeated.

If Justinian had had the good fortune to die in 540, he would have been remembered as the greatest of all Rome’s many emperors. Unfortunately for him, he lived. The 540s was a low, depressing decade for the Roman Empire. Khusro broke the endless peace, and a Persian army sacked the city of Antioch. The swift victories in the west collapsed into difficult wars of pacification, which at points the Romans seemed destined to lose.

December 29, 2023

The Christianization of England

Ed West‘s Christmas Day post recounted the beginnings of organized Christianity in England, thanks to the efforts of Roman missionaries sent by Pope Gregory I:

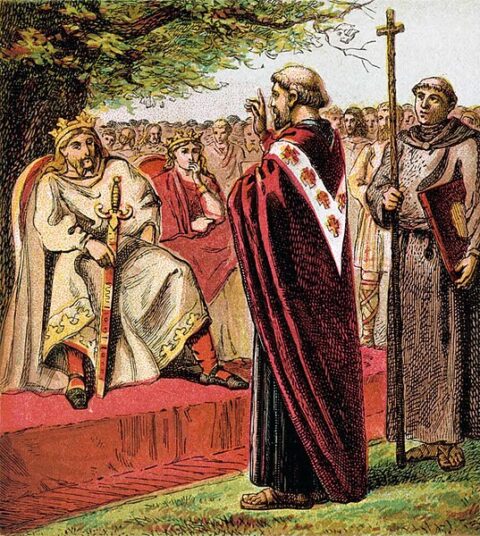

“Saint Augustine and the Saxons”

Illustration by Joseph Martin Kronheim from Pictures of English History, 1868 via Wikimedia Commons.

The story begins in sixth century Rome, once a city of a million people but now shrunk to a desolate town of a few thousand, no longer the capital of a great empire of even enjoying basic plumbing — a few decades earlier its aqueducts had been destroyed in the recent wars between the Goths and Byzantines, a final blow to the great city of antiquity. Under Pope Gregory I, the Church had effectively taken over what was left of the town, establishing it as the western headquarters of Christianity.

Rome was just one of five major Christian centres. Constantinople, the capital of the surviving eastern Roman Empire, was by this point far larger, and also claimed leadership of the Christian world — eventually the two would split in the Great Schism, but this was many centuries away. The other three great Christian centres — Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Antioch — would soon fall to Islam, a turn of events that would strengthen Rome’s spiritual position. And it was this Roman version of Christianity which came to shape the Anglo-Saxon world.

Gregory was a great reformer who is viewed by some historians as a sort of bridge between Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the founder of a new and reborn Rome, now a spiritual rather than a military empire. He is also the subject of the one great stories of early English history.

One day during the 570s, several years before he became pontiff, Gregory was walking around the marketplace when he spotted a pair of blond-haired pagan slave boys for sale. Thinking it tragic that such innocent-looking children should be ignorant of the Lord, he asked a trader where they came from, and was told they were “Anglii”, Angles. Gregory, who was fond of a pun, replied “Non Angli, sed Angeli” (not Angles, but angels), a bit of wordplay that still works fourteen centuries later. Not content with this, he asked what region they came from and was told “Deira” (today’s Yorkshire). “No,” he said, warming to the theme and presumably laughing to himself, “de ira” — they are blessed.

Impressed with his own punning, Gregory decided that the Angles and Saxons should be shown the true way. A further embellishment has the Pope punning on the name of the king of Deira, Elle, by saying he’d sing “hallelujah” if they were converted, but it seems dubious; in fact, the Anglo-Saxons were very fond of wordplay, which features a great deal in their surviving literature and without spoiling the story, we probably need to be slightly sceptical about whether Gregory actually said any of this.

The Pope ordered an abbot called Augustine to go to Kent to convert the heathens. We can only imagine how Augustine, having enjoyed a relatively nice life at a Benedictine monastery in Rome, must have felt about his new posting to some cold, faraway island, and he initially gave up halfway through his trip, leaving his entourage in southern Gaul while he went back to Rome to beg Gregory to call the thing off.

Yet he continued, and the island must have seemed like an unimaginably grim posting for the priest. Still, in the misery-ridden squalor that was sixth-century Britain, Kent was perhaps as good as it gets, in large part due to its links to the continent.

Gaul had been overrun by the Franks in the fifth century, but had essentially maintained Roman institutions and culture; the Frankish king Clovis had converted to Catholicism a century before, following relentless pressure from his wife, and then as now people in Britain tended to ape the fashions of those across the water.

The barbarians of Britain were grouped into tribes led by chieftains, the word for their warlords, cyning, eventually evolving into its modern usage of “king”. There were initially at least twelve small kingdoms, and various smaller tribal groupings, although by Augustine’s time a series of hostile takeovers had reduced this to eight — Kent, Sussex, Essex, and Wessex (the West Country and Thames Valley), East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Bernicia (the far North), and Deira (Yorkshire).

In 597, when the Italian delegation finally finished their long trip, Kent was ruled by King Ethelbert, supposedly a great-grandson of the semi-mythical Hengest. The king of Kent was married to a strong-willed Frankish princess called Bertha, and luckily for Augustine, Bertha was a Christian. She had only agreed to marry Ethelbert on condition that she was allowed to practise her religion, and to keep her own personal bishop.

Bertha persuaded her husband to talk to the missionary, but the king was perhaps paranoid that the Italian would try to bamboozle him with witchcraft, only agreeing to meet him under an oak tree, which to the early English had magical properties that could overpower the foreigner’s sorcery. (Oak trees had a strong association with religion and mysticism throughout Europe, being seen as the king of the trees and associated with Woden, Zeus, Jupiter, and all the other alpha male gods.)

Eventually, and persuaded by his wife, Ethelbert allowed Augustine to baptise 10,000 Kentish men on Christmas Day, 597, according to the chronicles. This is probably a wild exaggeration; 10,000 is often used as a figure in medieval history, and usually just means “quite a lot of people”.

December 20, 2023

Eat Like a Medieval Nun – Hildegard of Bingen’s Cookies of Joy

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 5 Sept 2023

(more…)

December 15, 2023

The Pagan Necropolis Under Vatican City

toldinstone

Published 1 Sept 2023Beneath the floor of St. Peter’s Basilica, an ancient Roman cemetery holds the secret to the origins of Vatican City.

(more…)

November 29, 2023

Alfred the Great

Ed West‘s new book is about the only English king to be known as “the Great”:

There are no portraits of King Alfred from his time period, so representations like this 1905 stained glass window in Bristol Cathedral are all we have to visually represent him.

Photo by Charles Eamer Kempe via Wikimedia Commons.

History was once the story of heroes, and there is no greater figure in England’s history than the man who saved, and helped create, the nation itself. As I’ve written before, Alfred the Great is more than just a historical figure to me. I have an almost Victorian reverence for his memory.

Alfred is the subject of my short book Saxons versus Vikings, which was published in the US in 2017 as the first part of a young adult history of medieval England. The UK edition is published today, available on Amazon or through the publishers. (use the code SV20 on the publisher’s site, valid until 30 November, which gives 20% off). It’s very much a beginner’s introduction, aimed at conveying the message that history is just one long black comedy.

The book charts the story of Alfred and his equally impressive grandson Athelstan, who went on to unify England in 927. In the centuries that followed Athelstan may have been considered the greater king, something we can sort of guess at by the fact that Ethelred the Unready named his first son Athelstan, and only his eighth Alfred, and royal naming patterns tend to reflect the prestige of previous monarchs.

Yet while Athelstan’s star faded in the medieval period, Alfred’s rose, and so by the fifteenth century the feeble-minded Henry VI was trying to have him made a saint. This didn’t happen, but Alfred is today the only English king to be styled “the Great”, and it was a word attached to him from quite an early stage. Even in the twelfth century the gossipy chronicler Matthew Paris is using the epithet, and says it’s in common use.

However, much of what is recorded of him only became known in Tudor times, partly by accident. Henry VIII’s break from Rome was to have a huge influence on our understanding of history, chiefly because so many of England’s records were stored in monasteries.

Before the development of universities, these had been the main intellectual centres in Christendom, indeed from where universities would grow. Now, along with relics, huge amounts of them would be lost, destroyed, sold … or preserved.

It was lucky that Matthew Parker, the sixteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury with a keen interest in history, had a particularly keen interest in Alfred. It was Parker who published Asser’s Life of Alfred in 1574, having found the manuscript after the dissolution of the monasteries, a book that found itself in the Ashburnham collection amassed by Sir Robert Cotton in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Sadly, the original Life was burned in a famous fire at Ashburnham House in Westminster on October 23, 1731. Boys from nearby Westminster School had gone into the blaze alongside the owner and his son to rescue manuscripts, but much was lost, among them the only surviving manuscript of the Life of Alfred, as well as that of Beowulf. In fact the majority of recorded Anglo-Saxon history had gone up in smoke in minutes.

A copy of Beowulf had also been made, although the poem only became widely known in the nineteenth century after being translated into modern English. The fire also destroyed the oldest copy of the Burghal Hidage, a unique document listing towns of Saxon England and provisions for defence made during the reign of Alfred’s son Edward the Elder. An eighth-century illuminated gospel book from Northumbria was also lost.

So it is lucky that Parker had had The Life of Alfred printed, even if he had made alterations in his copy that to historians are infuriating because they cannot be sure if they are authentic. He probably added the story about the cakes, for instance, although this had come from a different Anglo-Saxon source.

We also know that Archbishop Parker was a bit confused, or possibly just lying; he claimed Alfred had founded his old university, Oxford, which was clearly untrue, and he was probably trying to make his alma mater sound grander than Cambridge. Oxford graduates down the years have been known to do this on one or two occasions.

November 22, 2023

Another look at the “Great Divergence”

The latest book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf features Patrick Wyman’s The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World:

This is a weird Substack featuring an eclectic selection of books, but one of our recurring interests is the Great Divergence: why and how did the otherwise perfectly normal people living in the northwestern corner of Eurasia managed to become overwhelmingly wealthier and more powerful than any other group in human history? We’ve covered a few theories about what’s behind it — not marrying your cousins, coal, the analytic mindset (twice) — but there are lots of others we’ve never touched, including geographic and thus political fragmentation, proximity to the New World, and even the Black Death. So this is also a book about the Great Divergence, but unlike many of the others it doesn’t offer One Weird Trick to explain things. Instead, Wyman approaches the period between 1490 and 1530 through nine people, each of whom exemplifies one of the many shifts in European society, and so paints a portrait of a changing world.

Of course, he does point to a common thread woven through many of the changes: culture. Or, more specifically, the institutions1 surrounding money and credit that Europeans had spent the last few hundred years developing. But these weren’t themselves dispositive: after all, lots of people in lots of place at lots of times have been able to mobilize capital, and most of them don’t produce graphs that look like this. Really, the secret ingredient was — as Harold Macmillan said of the greatest challenge to his government — “events, dear boy, events”.2 Europe between 1490 to 1530 saw an unusually large number of innovations and opportunities for large-scale, capital-intensive undertakings, and already had the economic institutions in place to take advantage of them. One disruption fed on the next in a mutually-reinforcing process of social, political, religious, economic, and technological change that (Wyman argues) set Europe on the path towards global dominance.

Some of Wyman’s characters — Columbus, Martin Luther, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V — are intensely familiar, but he presents them with verve, as interested in giving you a feel for the individual and their world as in conveying biographical detail. (This is an underrated goal in the writing of history, but really invaluable; the “Cross Section: View from …” chapters were always my favorite part of Jacques Barzun’s idiosyncratic doorstopper From Dawn to Decadence.) This is particularly welcome when it comes to the chapters featuring some lesser-known figures: you may have heard of Jakob Fugger, but unless you’re a Wimsey-level fan of incunabula you’re probably unfamiliar with Aldus Manutius. One-handed man-at-arms Götz von Berlichingen becomes our lens for the chapter about the Military Revolution not because he played a particularly significant role but because he wrote a memoir, and small-time English wool merchant John Heritage is notable pretty much solely because his account book happened to survive into the present. But even with the stories “everyone knows”, Wyman takes several large steps back in order to contextualize that common knowledge: for example, were you aware that while before 1492 Columbus didn’t take any particularly unusual voyages, he did take an unparalleled number and variety of them, making him one of the best-travelled Atlantic sailors of his day? Did you know that Isabella’s inheritance of the Castilian throne was far from certain?3

As the book continues, Wyman can reference the cultural and technological shifts he described in earlier chapters. For instance, much of the Fuggers’ wealth came in the form of silver from deep new mines in the Tyrol. Building the mines required substantial capital — for their new, deeper tunnels and the expensive pumps to drain them, as well as for the furnaces and workshops to separate the copper from the silver via the relatively inefficient liquation process — and while everyone knew all along that the metals were there, it took the combination of a continent-wide bullion shortage and a rising demand for copper to cast bronze cannon (look back to the chapters on state formation and the military!) to make it worth anyone’s while to get them out. But it wasn’t only the Fuggers who made their money in these new mines: the money for Martin Luther’s education came from his father’s small-scale copper mining concern in eastern Germany. Grammar school in his hometown, a parish school nearby, and then four years at university cost Luther pater enough that he couldn’t follow it up for his younger sons (and from his point of view the was probably squandered when Martin became a monk instead of the intended lawyer who would be an asset in the frequent mining disputes), but such an education for even one son would have been out of reach if not for the printed texts on grammar, philosophy and law that made it all far more affordable.

Of course, the relationship between Luther and printing goes both ways. While Luther’s very existence as an educated man was enabled by the printing press, it was the intellectual and religious ferment he would kick off that made printing work.

1. Wyman glosses the term as “a shared understanding of the rules of a particular game … the systems, beliefs, norms and organizations that drive people to behave in particular way”, but it’s more or less what I’ve elsewhere called bundles of social technologies.

2. Apparently he may not have said this, but he should have so print the legend.

3. Isabella’s opponent, her half-niece Joanna, was married to King Afonso V of Portugal, so perhaps some degree of Iberian unification might still have followed. On the other hand, Afonso already had an adult son (King João II, widely admired as “the Perfect Prince” — Isabella always referred to him simply as el Hombre, “the Man”) who would have had no personal claim to Castile. Joanna and Afonso’s marriage was annulled on the perfectly true grounds of consanguinity — he was her uncle — after they lost the war, so they never had children, but if she had won perhaps João (who died without legitimate issue) could have been succeeded by a much younger half-Castilian half-brother. Certainly an Isabella relegated to Queen-Consort of Aragon would still have been a force to be reckoned with, but losing the knock-on effects of her reign (Columbus, Granada, the fate of the Sephardim, not to mention the eventual unification of most of Europe under Ferdinand and Isabella’s Habsburg grandson) makes all this a pretty good setup for an alternate history!

Even more fun: before she married Ferdinand of Aragon, there was discussion of Isabella’s betrothal to Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Yeah, that one.

November 21, 2023

“I couldn’t believe I was sitting in a court room where the prosecution discussed the interpretation of Bible verses”

In First Things, Sean Nelson recounts the trials of Päivi Räsänen, a Finnish parliamentarian who has been through several years of legal tribulation for expressing her religious views publicly:

“Blessed is the man who perseveres in the trial,” declares the Epistle of James. Finnish Member of Parliament Päivi Räsänen should count herself doubly blessed this week. She has now persevered through two trials over more than four years of legal troubles brought on merely for expressing her Christian faith. Following both trials, she has not only been acquitted, but also has been a shining example of a modern Christian life fearlessly lived.

On Tuesday, a Finnish Court of Appeal unanimously found MP Räsänen not guilty under Finland’s “hate speech” laws. If the decision stands — there is still a possibility of appeal to Finland’s Supreme Court — it will represent a bulwark for Christians and all people of good will wishing to live out their faith and contribute to social conversations over contentious issues.

Räsänen’s legal saga began on June 17, 2019. On that day, she tweeted a criticism of her church’s participation in a Helsinki Pride parade. She also included a picture of verses from her home Bible. Her case has come to be known as the “Bible Trial”.

Because she is a long-serving member of Parliament and a former Minister of the Interior, her tweet drew the ire of Finnish officials. While an initial police investigation found nothing criminal in her tweet — even writing that sounds absurd — the prosecutor’s office re-opened the matter to comb through her entire history of public utterances. The Helsinki prosecutor came back with an allegedly offensive pamphlet published in 2004 and a live radio interview from 2019. Räsänen was then charged with three counts of “hate speech” under a criminal code provision originally related to war crimes.

During her first trial in January 2022, the Helsinki prosecutor probed Räsänen with theological questions. Was it really possible to separate sin from the sinner, and condemn the former while loving the latter? Basic Christian belief rests on the distinction, as Räsänen explained, but the prosecutor was not convinced. Räsänen reflected at the time, “I couldn’t believe I was sitting in a court room where the prosecution discussed the interpretation of Bible verses”.

In March 2022, the trial court delivered a resounding victory for Räsänen, unanimously finding her not guilty. “It is not for the district court to interpret biblical concepts,” it said.

November 18, 2023

“René Girard’s famous book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning isn’t directly about Barack Obama being the Antichrist”

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander reviews I See Satan Fall Like Lightning by René Girard:

The phrase “I see Satan fall like lightning” comes from Luke 10:18. I’d previously encountered it on insane right-wing conspiracy theory websites. You can rephrase it as “I see Satan descend to earth in the form of lightning”. But “lightning” in Hebrew is barak. So the Bible says Satan will descend to Earth in the form of Barak. Seems like a relevant Bible verse for insane right-wing conspiracy theorists!

Philosopher / theologian Rene Girard’s famous book I See Satan Fall Like Lightning isn’t directly about Barack Obama being the Antichrist. It’s an ambitious theory-of-everything for anthropology, mythography, and the Judeo-Christian religion. After solving all of those venerable fields, it will, sort of, loop back to Barack Obama being the Antichrist. But it’ll do it in such an intellectual and polymathic Continental philosophy way that can’t even get mad.

Girard’s starting point is the similarity between Bible stories and pagan myths. You’ve heard about this before — dying-and-resurrecting gods, that sort of thing. You might expect Girard, a good Catholic, to reject these similarities. He doesn’t. He says they’re real and important. Pagan myths resemble the Bible because they’re both describing the same psychosocial process. The myths are distorted propaganda supporting the process, and the Bible is a clear-eyed description of the process which reveals it to be evil. Just as worshipful Soviet hagiographies of Stalin and sober historical analyses of Stalin will have many similarities (since they’re both describing Stalin), so there will be unavoidable resonances between myth and the Bible.

Girard calls this process “the single-victim process” or “Satan”. It goes like this:

- Most (all?) human desire is mimetic, ie based on copying other people’s desires. The Bible warns against coveting your neighbor’s stuff, because it knows people’s natural tendencies run that direction. It’s not that your neighbor has particularly good stuff. It’s that you want it because it’s your neighbor’s. Think of two children playing in a room full of toys. One child picks up Toy #368 and starts playing with it. Then the other child tries to take it, ignoring all the hundreds of other toys available. It’s valuable because someone else wants it.

- As with the two children, conflict is inevitable. As the mimetic process intensifies, everyone goes from complicated individuals with individual wants, to copies of their neighbors (ie their desires copy their neighbors’ desires, and they become the sort of people who would have those desires). Alliances form and dissipate. There is a war of all against all. The social fabric starts to collapse.

- Instead of letting the social fabric collapse, everyone suddenly turns their ire on one person, the victim. Maybe this person is a foreigner, or a contrarian, or just ugly. The transition from individuals to a mob reaches a crescendo. The mob, with one will, murders the victim (or maybe just exiles them).

- Then everything is kind of okay! The murder relieves the built-up tension. People feel like they can have their own desires again, and stop coveting their neighbors’ stuff quite so hard, at least for a while. Society does not collapse. If there was no civilization before, maybe people take advantage of this period of relative peace to found civilization.

- (Optional step 5) Seems pretty impressive that killing one victim could cause all this peace and civilization! The former mob declares their victim to be a god. Killing the god was the necessary prerequisite to civilization. Now the god probably reigns in heaven or something. Maybe they die and resurrect every year. Whatever.

- Rinse and repeat.

Girard is against this process. Not just because it involves violent mobs lynching innocent people (although it does), but because that step perpetuates the whole cycle: people greedily desiring whatever their neighbors have, people hating their neighbors, internecine war of all against all. He dubs the process Satan, based partly on the original Hebrew meaning of Satan as “prosecutor”. Satan is the force that tells people that the victim is guilty and deserves to be lynched.

(and did you know that Paraclete, the Greek word for the Holy Spirit, originally meant “defense attorney”? The Paraclete is the force that — no, we’ll get to that later).

Are all myths and Bible stories really about this process? Girard says yes. For example, consider the myth of Oedipus. Around the end, Thebes is stricken by plague (Girard says plagues should usually be interpreted metaphorically as social plagues, ie discord). Everyone goes to the oracle and asks for a solution. The oracle says that someone has killed his father and married his mother, and the plague won’t end until that person is removed. It is revealed that Oedipus is the culprit. The mob expels Oedipus from the city, and the plague ends.

Okay, that’s one myth. Are there others?

November 5, 2023

Guy Fawkes and The Gunpowder Plot 1605

The History Chap

Published 4 Nov 2022The story behind Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, the audacious plan to kill the king of England. It is also the complicated story behind our annual Bonfire Night celebrations.

In 1605 a group of dissident Catholics came within a whisker of one of the greatest assassination coups in history — blowing up the King of England, and his government as he attended parliament in London. 36 barrels of gunpowder (approximately 1 tonne of explosives) had been placed directly under where he would open parliament. Experts estimate that no one within 300 feet would have survived.

Had it succeeded it would have rivalled 9/11 in its audacity and would have changed English (& arguably world) history forever. But who were the plotters, what were they trying to achieve and how close did they really come to success? Were they freedom fighters or 17th century terrorists? And why is only one conspirator, Guy Fawkes, remembered when he wasn’t even the brains behind the operation?

After years of persecution by England’s Protestants, a small group of Catholic nobles under Robert Catesby (aka Robin Catesby) decided to take matters into their own hands and blow up the king (King James I of England / James VI of Scotland) whilst he attended parliament in London.

Guy Fawkes (aka Guido Fawkes) smuggled 36 barrels of gunpowder into a cellar directly beneath the hall where parliament would meet in the Palace of Westminster. In the early hours of 5th November 1605, he was arrested by guards who had been tipped off about the gunpowder plot. After three days of torture in the Tower of London, Guy Fawkes finally broke and named his fellow conspirators.

The conspirators, under Robert Catesby, had fled London for the English midlands where they hoped to abduct the king’s daughter and organise a catholic rising. Both failed to materialise and Catesby’s small band were surrounded by a government militia at Holbeach House, just outside Kingswinford in Staffordshire. A brief shoot-out resulted in the death of some of the Catholic rebels (including their leader, Catesby) and the arrest of the others.

The surviving gunpowder plotters (including Guy Fawkes) were executed in London at the end of January 1606, by the grisly execution reserved for traitors — Hanged, drawn and quartered (quite literally a “living death”).

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a complete failure but the event is still celebrated on the 5th November every year on Bonfire Night.

(more…)

September 20, 2023

Christian views on men and women

The most recent book review from Mr. and Mrs. Psmith discusses Brian Patrick Mitchell’s Origen’s Revenge: The Greek and Hebrew Roots of Christian Thinking on Male and Female:

The following is an email exchange between the Psmiths, edited slightly for clarity.

John: You know dear, we’ve been writing this book review Substack for eight months now, ever since that crazy New Year’s resolution of ours, but we still haven’t done “the gender one”. And I feel like we have a real competitive advantage at this, since both sides of the unbridgeable epistemic chasm between the sexes are represented here. So let’s settle some of the eternal questions: Can men and women be friends? Who got the worse deal out of the curse in the Garden of Eden? And what’s up with your abysmal grip strength anyway?

I was perplexed by these and other questions, but then I picked up this book on the theology of gender, and it all got a lot clearer. The author is Deacon Brian Patrick Mitchell, an Eastern Orthodox clergyman and retired military officer. In a previous life, Mitchell testified before the Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces and then followed that up with a book called Women in the Military: Flirting with Disaster, so he’s been interested in the differences between men and women for a while.

People have been observing for centuries that Christianity can be a little bit schizophrenic on the subject of gender relations. From the earliest days of the Apostolic era, there are two strains in evidence within Christianity: one which shores up the gender divisions common to most agricultural societies, and another which radically transcends them. Oftentimes both strains are visible within a single person! Thus you have the Apostle Paul on the one hand saying in his letter to the Ephesians:

Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body. Therefore as the church is subject unto Christ, so let the wives be to their own husbands in every thing. (Ephesians 5:22-24)

But then in Galatians:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus. (Galatians 3:28)

For as long as Christianity has existed, there have been people emphasizing one of these tendencies as the “true” Christian message on gender while attempting to minimize the other. Sometimes these arguments are interesting and sometimes they bring out something important (I’m a fan of Sarah Ruden’s Paul Among the People on the one side, and of Toby Sumpter’s fiery homilies on the other), but I think in both cases they’re falling into the error of trying to simplify something that is actually complicated. There’s a certain kind of person who can’t handle inconsistency, and that kind of person is going to have trouble with Christianity, because to a finite being the products of an infinite mind will sometimes appear inconsistent. Does Christianity want women to be subject to men, or does it want men and women to transcend their natures? The answer is very clearly both.

Mitchell’s book is compelling because it doesn’t try to minimize or hide one of these tendencies, but acknowledges up front that they’re both there and both have to be struggled with. It then advances the novel (as far as I know) argument that these two tendencies with regard to gender relations actually reflect the two major ethnic and cultural influences on the early Church: Hebrew and Greek.

The ancient Hebrew attitudes towards male and female are apparent from the beginning of the Bible: God creates Eve from out of Adam’s rib, and she is called Woman because she was taken out from Man. Thus the woman is subordinated to the man, yet fundamentally made of the same stuff as him. God calls the division of humanity into men and women good, He blesses families and helps barren women conceive, He commands His people to be fruitful and to multiply, and He promises Abraham that his seed shall be numbered as the stars of heaven. The entire Old Testament is a story of families, sometimes dysfunctional families, but families nonetheless, as opposed to lone men roaming the earth as in the Iliad or Bronze Age Mindset. Male headship is assumed, but it’s also assumed that men are fundamentally incomplete without something that only women can give them: a home, a future, and the thing that makes both, children.

So in Mitchell’s telling, the Hebrew legacy is responsible for the more “trad” side of early Christianity. What about the Greeks? Well we already discussed in our joint review of Fustel de Coulanges’ The Ancient City how ancient Greek society was basically the world of gangster rap: honor, boasting, violence, women as trophies, women as a way of keeping score, women torn wailing from the arms of their parents or husbands and forced into marriage or concubinage or outright slavery. You will be shocked to learn that this culture did not hold a high opinion of women, procreation, or the marital union. Greek philosophy is a massively complicated and diverse beast, but there’s a strong tendency within it to associate women with physicality, nature, and brute matter, and to disdain all of these things in favor of rationality, spirit, and the intellect (all coded as male).

Our readers are probably thinking, “Hang on a minute, I thought the Hebrews were the patriarchal ones, do you mean to say that the hyper-masculine and hyper-misogynistic culture was the one that decided maleness and femaleness didn’t matter?” Well yes I do, and it’s pretty easy to see why if one hasn’t been totally brainwashed by modernity, but maybe it’ll be more convincing if a woman explains it to them.

Jane: Well, I think you gave a pretty accurate description of actually-existing ancient Greek culture, but we have to remember that the Church Fathers weren’t classicists poring through the corpus trying to accurately characterize the past. Rather, they were men of late antiquity, mostly educated in a “Great Books” canon heavy on the classical philosophy — and the worldview of philosophers is often quite different from the general norms and presuppositions of their society as a whole. (Not that modern — by which I mean post-1600 — classicists have always recognized this; E.R. Dodds’s The Greeks and the Irrational is considered a seminal work of classical scholarship precisely because it undercuts a long tradition of taking the philosophers as representative of their culture rather than in conflict with it.)1 So the direct influence on early Christians wasn’t the world Fustel de Coulanges describes (which covers roughly the Greek Dark Ages through the Archaic period), but the texts of the period that came after, as interpreted by an even later era. It’s a bit like looking at our contemporary small-l liberals, who draw heavily on a tradition that rose out of Enlightenment philosophy, which in turn was an outgrowth of and/or reaction to the medieval and early modern worlds: they’re not not connected to all that, but Boethius is not going to be the most helpful context for reading Rorty. You should probably look at Locke instead.

1. Bonus, and shorter, Dodds: “On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex“, which you probably do too.

September 7, 2023

History Summarized: Iceland’s Hallgrimskirkja

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 26 May 2023The name is more visually complicated than the church itself.

I tried my best to pronounce all the Icelandic correctly but that LL sound is TRICKY.SOURCES & Further Reading:

Great Courses lectures “Iceland’s Independence” and “The Capital and Beyond in Southwest Iceland” from The Great Tours Iceland by Jennifer Verdolin, “Iceland’s Hallgrimskirkja” from World’s Greatest Churches by William R. Cook. Plus, two visits to Iceland and a lot of time spent staring at the thing.

(more…)

August 21, 2023

QotD: Effrontery, snake oil and TV preachers

… effrontery has made great strides as a key to success in life, and indeed quite ordinary people now employ it routinely. There are consultants in effrontery training who not only commit it themselves but teach others how to commit it, and charge large sums for doing so. There was a time when self-praise was regarded as no praise, rather the reverse; but now it is a prerequisite for advancement.

The other day I was sent a video of a young woman — elegant, attractive, and very self-confident — giving a seminar on how other young women, one of them the daughter of a friend, could and should change their lives for the better. In a way, I admired the leader of the seminar’s effrontery (just as I secretly admire Thomas Holloway’s). She spoke in pure, unadulterated clichés, practically contentless, but with such force of conviction that, if you discounted what she actually said, you might have thought that she was a person of profound insight with a vocation for imparting it to others. Her audience was as lambs to the slaughter, or at least to the fleece; they had paid a large sum of money to listen to mental pabulum that would make the recitation of a bus timetable seem intellectually stimulating.

On catching glimpses in the past of American television evangelists, it was always a cause of wonderment to me that anyone could look at or listen to them without immediately perceiving their fraudulence. This fraudulence was so obvious that it was like a physical characteristic, such as height or weight or color of hair, or alternatively like an emanation, such as body odor (incidentally, pictures of Guevara always suggest, to me at any rate, that he smelled). How could people fail to perceive it? Obviously, many did not, for the evangelists were very successful — financially, that is, the only criterion that counted for them.

But the attendees of the seminar of which I saw a video clip were well educated, and still they did not perceive the vacuity, and therefore the fraudulence, of the seminar that they attended at such great expense to themselves.

But was not my own surprise at their gullibility a manifestation of my own gullibility, in supposing that intelligence and education make a man wise, rather than more sophisticated in his foolishness?

But at least most of their victims were uneducated, relatively simple folk.

Theodore Dalrymple, “The Way of Che”, Taki’s Magazine, 2017-10-28.

August 8, 2023

QotD: The British imperial educational “system”

The history of “education”, of the university system, whatever you want to call it, is long and complicated and fascinating, but not really germane. Like all human institutions, “educational” ones grew organically around what were originally very different foundations, the way coral reefs form around shipwrecks. Oversimplifying for clarity: back in the day, “schools” were supposed to handle education […] while universities were for training. That being the case, very few who attended universities emerged with degrees — a man got what training he needed for his future career, and unless that future career was “senior churchman”, the full Bachelor of Arts route was pretty much pointless.

(At the risk of straying too far afield, let’s briefly note that “senior churchman” was a common, indeed almost traditional, career path for the spare sons of the aristocracy. Well into the 18th century, every titled parent’s goal was “an heir and a spare”, with the heir destined for the title and castle and the spare earmarked for the church … but not, of course, as some humble parish priest. It was pretty common for bishops or abbots, and sometimes even cardinals, to be ordained on the day they took over their bishoprics. See, for example, Cesare Borgia. Meanwhile the illiterate, superstitious, brutish parish priest was a figure of satire throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. A guy like Thomas Wolsey was hated, in no small part, precisely because he was a commoner who leveraged his formal education into a senior church gig, taking a bunch of plum positions away from the aristocracy’s spare sons in the process).

That being the case — that schools were for education, universities for training — the fascinating spectacle of some 18 year old fop fresh out of Eton being sent to govern the Punjab makes a lot more sense. His character, formed by his education (in our sense), was considered sufficient; he’d pick up such technical training as he needed on the job … or employ trained technicians to do it for him. So too, of course, with the army, and the more you know about the British Army before the 20th century, the more you’re amazed that they managed to win anything, much less an empire — the heir’s spare’s spare traditionally went into the army, buying his commission outright, which meant that quite senior commands could, and often did, go to snotnosed teenagers who didn’t know their left flank from their right.

Alas, governments back in the days were severely under-bureaucratized, meaning that the aristocracy lacked sufficient spares to fill all the technician roles the heirs required in a rapidly urbanizing, globalizing world… which meant that talented commoners had to be employed to fill the gaps. See e.g. Wolsey, above. The problem with that, though, is that you can’t have some dirty-arsed commoner, however skilled, wiping his nose on his sleeve while in the presence of His Lordship, so universities took on a socializing function. And so (again, grossly oversimplifying for clarity) the “bachelor of arts” was born, meaning “a technician with the social savvy to work closely with his betters”. A good example is Thomas Hobbes, whose official job title in the Earl of Devonshire’s household was “tutor”, but whose function was basically “intellectual technician” — he was a kind of man-of-all-work for anything white collar …

At that point, if there had been a “system” of any kind, what the system’s designers should’ve done is set up finishing schools. The “universities” of Oxford, Cambridge, etc. are made up of various “colleges” anyway, each with their own rules and traditions and house colors and all that Harry Potter shit. Their Lordships should’ve gotten together and endowed another college for the sole purpose of knocking manners into ambitious commoners on the make (Wolsey might actually have had something like this in mind with Cardinal College … alas).

But they didn’t, and so the professors at the traditional colleges were forced into a role for which they were not designed, and unqualified. That tends to happen a lot — have you noticed? It actually happened to them twice, once with the need for technicians-with-manners became apparent, and then again when the realization dawned — as it did by the 1700s, if not earlier — that some subjects, like chemistry, require not just technicians and technician-trainers, but researchers. Hard to blame the “system” for this, since of course there is no “system”, but also because such a thing would be ruinously expensive.

Hence by the time an actual system came into being — in Prussia, around 1800 — the professors awkwardly inhabited the three roles we started with. The Professor of Chemistry, say, was supposed to conduct research while training technicians-with-manners. As with the pre-machinegun British army, the astounding thing is that they managed to pull it off at all, much less to such consistently high quality. They were real men back then …

Severian, “Education Reform”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-11-17.