Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 14 Aug 2020The quintessential Irish mythological text, and … it’s about getting steamrolled by invaders. Now that’s what I call brand consistency!

Our content is intended for teenage audiences and up.

PATREON: https://www.Patreon.com/OSP

DISCORD: https://discord.gg/kguuvvq

MERCH LINKS: https://www.redbubble.com/people/OSPY…

OUR WEBSITE: https://www.OverlySarcasticProductions.com

Find us on Twitter https://www.Twitter.com/OSPYouTube

Find us on Reddit https://www.Reddit.com/r/OSP/

August 15, 2020

Miscellaneous Myths: The Book Of Invasions

August 14, 2020

August 7, 2020

QotD: Celibacy and chastity

Despite the common misunderstanding of the word, “celibate” does not refer to someone who abstains from sex. “Celibate” refers to someone who forgoes marriage — the part about not having sex is implied, at least in the Christian world, give or take an Alexander VI or two. “Chaste,” at the same time, doesn’t quite mean what people think it does: It refers principally to the abstention from extramarital sex, which in the case of the celibate means abstention from sex categorically. But chastity is part of marriage, too, describing a reverent attitude toward sex. In the Christian view (which is to say, in the view of Western civilization until ten minutes ago), the procreative act is the means by which men and women in union with one another participate in God’s creative work. “Chastity” means a lot more than mere abstinence. Chastity isn’t some kind of genital veganism.

There has been some pretty elevated stuff written on that subject, and if you want to take that particular high road, then Professor Robert George of Princeton is your guy. But consider the low road, too. There’s another conclusion, maybe a little bit cynical, that could be drawn from this: If you are a sexually frustrated young man, the smart play would be to join a church.

Kevin D. Williamson, “Advice for Incels”, National Review, 2018-05-10.

August 6, 2020

Rhodes: A Short History

History Time

Published 2 Mar 2017*****This was one of the first videos I ever made.

******Subscribe for much better narration on the newer videos and tons more historical awesomeness*****Situated at a crossroads between East and West, in a strategic location between the Aegean and the Mediterranean, Rhodes has long been fought over by the surrounding powers. As a result, Rhodes is one of the most historic sites on Earth.

If you liked this video and have as little as a dollar to spare then please consider supporting me on Patreon for more and better content in the future:- http://www.patreon.com/historytimeUK

Are you a budding artist, illustrator, cartographer, or music producer? Send me a message! No matter how professional you are or even if you’re just starting out, I can always use new music and images in my videos. Get in touch! I’d love to hear from you.

I’ve also compiled a reading list of my favourite history books via the Amazon influencer program. If you do choose to purchase any of these incredible sources of information, many of which form the basis of my videos, then Amazon will send me a tiny fraction of the earnings (as long as you do it through the link) (this means more and better content in the future) I’ll keep adding to and updating the list as time goes on:-

https://www.amazon.com/shop/historytimeI try to use copyright free images at all times. However if I have used any of your artwork or maps then please don’t hesitate to contact me and I’ll be more than happy to give the appropriate credit.

—Join the History Time community on social media:-

Instagram:-

https://www.instagram.com/historytime…

Twitter:-

https://twitter.com/HistoryTimePete

August 5, 2020

QotD: Responsibility

I have always been deeply suspicious of the word “responsibility”. It has again and again sounded like someone else telling me that I must do what he wants me to do rather than what I want to do. If he is paying my wages, then fair enough. But if he is explaining why I should vote for him, and support everything he does once he has got the job he is seeking, not so fair.

The sort of thing I mean is when a British Conservative Party politician says, perhaps to a room full of people who, like me, take the idea of personal liberty very seriously: Yes, I believe, passionately, in personal liberty. The politician maybe then expands upon this idea, often with regard to how commercial life works far better if people engaged in commerce are able to make their own decisions about which projects they will undertake and which risks they will walk towards and which risks they will avoid. If business is all coerced, it won’t be nearly so beneficial. We will all get poorer. Yay freedom.

But.

But … “responsibility”. We should all have freedom, yes, but we also have, or should have, “responsibility”. Sometimes there then follows a list of things that we should do or should refrain from doing, for each of which alleged responsibility there is a law which he favours and which we must obey. At other times, such a list is merely implied. So, freedom, but not freedom.

The problem with politicians talking about responsibility is that their particular concern is and should be the law, law being organised compulsion. And too often, their talk of responsibility serves only to drag into prominence yet more laws about what people must and must not do with their lives. But because the word “responsibility” sounds so virtuous, this list of anti-freedom laws becomes hard to argue against, even inside one’s own head. Am I opposed to “responsibility”? Increasingly, I have found myself saying: To hell with it. Yes.

I have often been similarly resistant to the language of Christianity, of the sort that dominates what is being said in churches around the world today. How many times in history have acts of tyranny been justified by the tyrant saying something like: We must all bear our crosses in life, and here, this cross is yours. “God is on my side. Obey my orders.” The truth about the potential of life to inflict pain becomes the excuse to inflict further pain.

Brian Micklethwait, “Jordan Peterson on responsibility – and on why it is important that he is not a politician”, Samizdata, 2018-03-30.

July 27, 2020

H.L. Mencken

In the latest Libertarian Enterprise, Eric Oppen (with whom I’ve had a few brief email conversations) discusses the work of the “Sage of Baltimore”:

I would say that, on the whole, Mencken is still quite readable and enjoyable, and many of his observations on the American scene are still as valid as when he made them. He has his weaknesses. He’s not much of an historian, which limits him when he takes up historical subjects. He never got over what he saw as the unfair treatment the German cause got in the American press between 1914 and the entry of the US into World War One. He also often identifies people as Jewish or black when it’s not really relevant to what he’s saying, but this was more a custom of his time than out-and-out bigotry. While he often has uncomplimentary things to say about Jews, and blacks, his greatest scorn is reserved for “the lintheads” — his term for the poor whites of the South. He regarded them as barely worthy of human status.

[…] his views on most subjects were quite compatible with libertarian positions. He was an inveterate opponent of government overreaching (which was behind a lot of his ferocious opposition to Prohibition) and while I don’t think he’d approve of drug use, he’d see our War on (Some Unpopular) Drugs as the assault on the Constitution that it is. While he was by no means hostile to blacks, and went out of his way to promote black writers (many of the figures in the “Harlem Renaissance” owed a lot to his support), he’d also denounce affirmative action and our current frenzy of “anti-racism” in scathing terms. His views on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and how it has been turned into an alternate, and superior, Constitution would probably scorch the paint off the walls.

Mencken’s views on people’s private lives would have infuriated many of his contemporaries. While he disapproved of homosexuality, referring to it negatively in entries in his private diaries, he was by no means a howling “homophobe.” His writings on the travails of Oscar Wilde are very sympathetic to Wilde’s sufferings, which Mencken thought were wholly disproportionate to what he was known to have done. Mencken referred to Lord Alfred Douglas, in a review of Douglas’ book about Wilde, as a Tartuffe — that is to say, a posturing hypocrite.

Having been a reporter for years in Baltimore, back when reporters were very like the old film noir view of them, Mencken was very much a man of the world, and inclined to great tolerance on others’ sex lives. When he wrote of prostitutes, he refrained from the sort of pious moralizing that was expected in his time. He said that prostitutes often actively preferred their profession to other work available to them, and that most of them ended up respectably married. He kept his own love life very private, and was a faithful husband to his wife throughout their brief marriage, but he does mention, here and there, having had other lovers, whom he does not name even in writings designated to come to light only long after everybody involved was dead. By his own account in his Diary, he lost his virginity at age fourteen to a girl of his own age, who had already had other experiences before him. He felt that such experiences, unless pregnancy happened, did no one any harm.

While he was an atheist, Mencken had no particular hostility to religion per se, no matter what the Fundamentalists of his day thought. His book Treatise on the Gods makes interesting reading, although it is marred, in my view, by Mencken’s lack of knowledge of languages. He praises Christianity for having “the most gorgeous poetry,” but as far as I know, he could not read Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek, and was thinking in terms of the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. However, the book is still worth reading, although a serious student of the subject would find it limited.

If you’ve been a regular visitor to the blog, you’ll know I have a huge regard for H.L. Mencken’s work and there are many Mencken quotes that have done duty as QotD entries over the years.

July 26, 2020

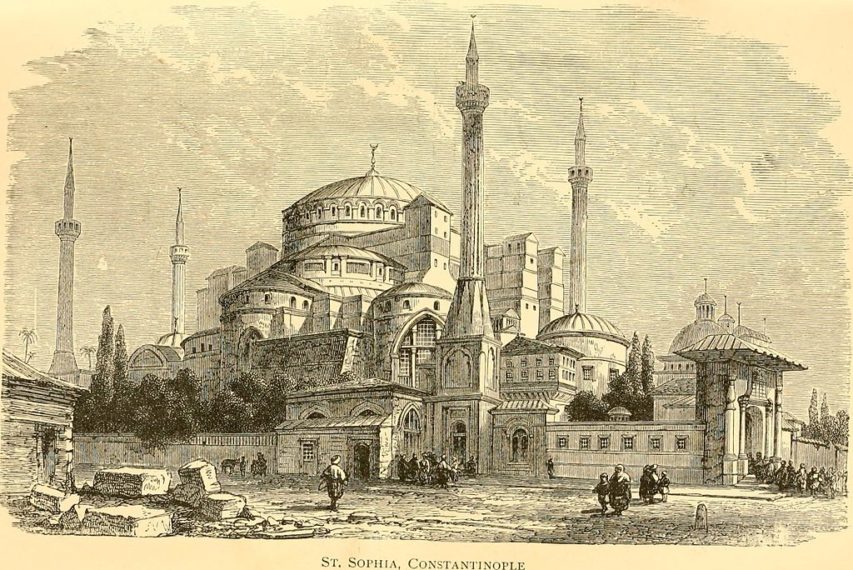

Hagia Sophia

Lars Brownworth (author of the excellent Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization) on the building of the Hagia Sophia by Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian in Constantinople:

Illustration of the Hagia Sophia from European History: An outline of its development by George Burton Adams, 1899.

Wikimedia Commons

The Hagia Sophia was the brainchild of a unique figure in history. At birth, Justinian was a nobody among nobodies in a grindingly poor part of what is today North Macedonia. By his mid-40s, he was a Byzantine emperor. His appetites were large, his dreams larger. The man who knew what it was like to have nothing gave new meaning to the idea of luxury. For one memorable celebration, he spent almost two tons of gold on decorations.

Justinian had no time for small things. By the second year of his reign, he had decided to codify all of Roman law, founded several new cities, and had started construction on at least eight new churches.

The money for all these projects inevitably came from the public. And by the fifth year of his reign, his subjects had had enough. Already upset by rampant corruption, an inefficient bureaucracy, and crushing taxes, they hit the boiling point when Justinian severely restricted public games. A mob tore through the streets, overwhelming the unprepared police forces. Several stores were set on fire, and the wind quickly spread the flames to a nearby hospital, which burned down with its patients inside. An inferno raged. For five long days, Constantinople burned.

By the time Justinian reasserted control, more than 30,000 citizens were dead, and perhaps a third of the city was a blackened shell. It looked as if some barbarian horde had sacked the capital. The fact that its own people had inflicted such a wound hovered like a black cloud over the streets.

Characteristically, Justinian saw a perfect opportunity within the ashes. This was a blank canvas on which to create a new city in his image. The transformation would begin with the cathedral. The original building, known simply as the Magna Ecclesia — the Great Church — had been built by a son of Constantine the Great in the fourth century, but had burned down a few decades later. Since it was a standard Roman basilica — a large hall with square walls and angled wooden roof — it had been fairly easy to rebuild along the same lines.

But of course, Justinian had no intention of following the tired plans of an earlier age. This was a chance to remake the cathedral on a new scale, something worthy of the ages. It was to be nothing short of a revolution, equal parts art and architecture, the enduring grandeur of the emperor himself frozen in physical form.

Everything about this project was audacious, including his selection of architects. Instead of choosing a traditional builder, he picked two teachers who — like himself — had more vision than practical experience. This was a lifelong pattern with Justinian. He had a habit of plucking genius out of the common crush; his wife was a reformed prostitute, and his greatest generals were an elderly eunuch and a former bodyguard.

The emperor’s instructions to Isidore of Miletus, a physics teacher, and Anthemius of Tralles, a mathematician, should have terrified them. They merely had to design and successfully build a church unlike anything else the world had seen. Sheer scale wasn’t enough — the empire was full of grand monuments and immense sculpture. This had to be something different, something fitting for the new golden age that was dawning. Expense wasn’t an issue, but speed was. Justinian was already in his 50s, and he didn’t intend to have some successor apply the final coat of paint and claim the project as his own.

July 22, 2020

Glorious Revolution | 3 Minute History

Jabzy

Published 21 Jul 2015Sorry about the delay I’ve been without internet while I’ve moved apartment. And thanks for the 9,000 subs

Thanks to Xios, Alan Haskayne, Lachlan Lindenmayer, William Crabb, Derpvic, Seth Reeves and all my other Patrons. If you want to help out – https://www.patreon.com/Jabzy?ty=h

Please let me know if I’ve forgot to mention you, I’m a little disorganized without internet.

July 16, 2020

The Witchfinder General Defends the Great State of Massachusetts

Atun-Shei Films

Published 14 Jul 2020The greate Common-Wealth of Massachusetts is oft unjustly slandered. The Ignorant shall saye that the inhabitants of this fair colonie drive Carriages like mad-men; that they are too much enamored with Crimson Stockings and Those Who Love Their Countrie; and that they are as sullen and cruel as a New-England winter. The Witchfinder General dis-proves this Slander, and denounces it for the Profession of Heresy that it is.

Support Atun-Shei Films on Patreon ► https://www.patreon.com/atunsheifilms

Leave a Tip via Paypal ► https://www.paypal.me/atunsheifilms (Between now and October, all donations made here will go toward the production of The Sudbury Devil, our historical feature film)

Original Music by Dillon DeRosa ► http://dillonderosa.com/

#Puritan #Witch #Boston

Watch our film ALIEN, BABY! free with Prime ► http://a.co/d/3QjqOWv

Reddit ► https://www.reddit.com/r/atunsheifilms

Twitter ► https://twitter.com/atun_shei

Instagram ► https://www.instagram.com/atunsheifilms

Merch ► https://atun-sheifilms.bandcamp.com

From the comments:

Atun-Shei Films

1 day ago

The awesome baroque song at the end of this video is the brand-new Witchfinder General theme composed by the insanely talented Dillon DeRosa, who’s currently hard at work putting together a new theme for Checkmate Lincolnites and a bunch of other incidental music for this channel. His music was also one of the best parts of my movie ALIEN, BABY! and he’s done a bunch of other film scores as well. Check out his website, and never forget that thou art a wretched sinner, utterly unworthy of God’s love: http://dillonderosa.com/

July 12, 2020

Restoring Notre Dame – “The matter will be solved in a serene manner, and on time”

Andrew Sullivan breathes a sigh of relief that the French government is going to properly restore the fire-damaged cathedral rather than — shudder — re-imagine it:

A small note of hope. The fiery destruction of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris was one of the more searing occasions for acute depression these past couple of years, and it was not without some stiff competition. Yes, it’s just a building and not a human being. But it is also far more than a building. It’s a reminder to me of what the faith of Europe was once capable of; of a civilization proud, rather than ashamed, of itself; and of a lost world when beauty itself was a virtue and connected to a view of the whole of creation that made sense and provided hope and meaning.

Much of that has disappeared, of course, which is why the physical remains of a previous civilization are so precious. And so I was terrified, to be honest, that our own aesthetically squalid and spiritually devoid ideas of what architecture should be might ruin the rebuilding. And when you take a look at some of the original wackier proposed designs — you can see models for seven modernist monstrosities in this Architectural Digest compilation here — you can see what I was worried about. One tops the cathedral with a greenhouse; another with a swimming pool. One hideous version has the entire roof and new spire made out of stained glass; another re-creates a ball of fire in metallic form. Norman Foster’s design turned the place into a huge greenhouse, or as one Twitter wag put it, like “a conference center in Essex.” This was all because Macron himself hinted that he preferred a “contemporary architectural gesture.”

Mercifully, the chief architect put in charge of the restoration, Philippe Villeneuve, had some strong feelings on the matter. He wanted the original restored in its entirety, period. When I say “strong feelings,” I refer to the following statement he made on television last year: “I will restore it identically, and it will be me, or they will build a modern spire, and it won’t be me.” When President Macron’s somewhat more ambitious adviser on the project, General Jean-Louis Georgelin, testified on the matter to the National Assembly’s cultural-affairs committee, sparks flew when Villeneuve’s statement was brought up. Georgelin said: “The matter will be solved in a serene manner, and on time. I have already explained to the chief architect that he should just shut his big mouth, and I will do it again.” “On time” meant in time for Paris’s hosting of the Olympics in 2024.

And since that time is fast running out, and designing, approving and building a modernist tower would take too long, we found out yesterday that the restoration will be identical after all. It will copy the 19th-century Gothic design exactly. The contemporary gesture that Macron desired will instead be a giant Victorian single finger to all the modernists who would have destroyed it. And who knows how many generations in the future will be thankful.

Two of the “re-imagined” restorations:

July 11, 2020

The “Puritan Moment” of The Current Year

Nigel Jones on the long history of struggle between British puritans and libertarians:

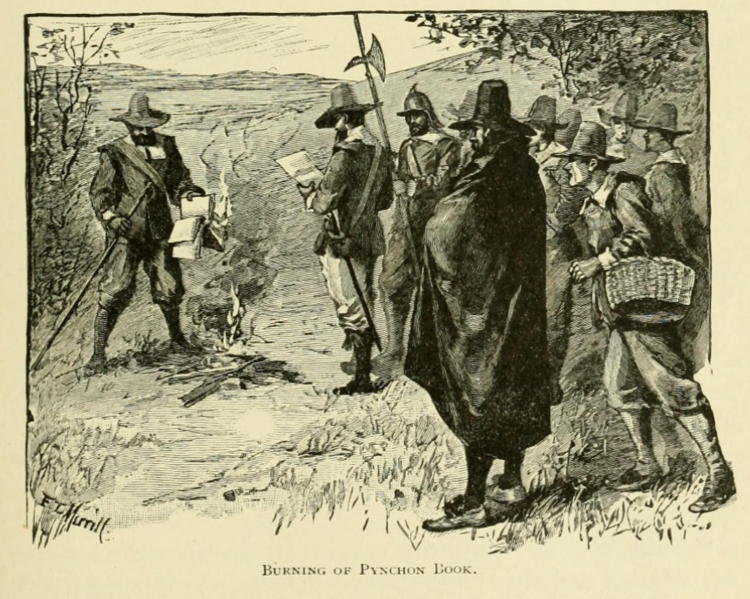

Portrayal of the burning of copies of William Pynchon’s book The Meritous Price of Our Redemption by early colonists of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, who saw his book as heresy; it was the first-ever banned book in the New World and only 4 original copies are known to survive today.

Engraving by F.T. Merrill in The History of Springfield for the Young by Charles Barrows, 1921.

Behind the wave of Wokeism that has swept and is now swamping Anglo-American Culture, is a pattern that has recurred throughout British History since the early 17th century. This is the pendulum that regularly swings between periods of joyful Libertarianism and purse lipped Puritanism.

Puritanism takes its name from the Calvinist religious movement that arose during the Protestant Reformation, partly in reaction to the explosive cultural Renaissance of the Elizabethan era – the age of Shakespeare, Marlowe, Ralegh and John Donne.

The Puritans exported their austere doctrines to America aboard the Mayflower, where they eventually became one of the building blocks of the USA, and briefly achieved political power in England after the Civil War in the forbidding guise of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth.

We all have a mental picture of the Puritans in action. Sombrely dressed in black and grey, smashing the statues of saints, preaching their varied versions of the scriptures, and policing and banning anything when they suspected people of enjoying themselves, from Christmas festivities, to theatres, to fornicating for pleasure rather than reproduction. The Puritans endeavoured to dictate what people could think, speak and write. If this rings any bells with Wokeism, that is surely not coincidental.

There was an inevitable vengeful reaction to this po-faced culture of control and repression, and it soon came with the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660. King Charles II exemplified in his own libidinous person, with his myriad mistresses and tribe of illegitimate children, the loose culture of license that spread out from his court like a stain. This was the easy going Age of Lord Rochester and Nell Gwynn, so disapprovingly, if hypocritically, frowned on in the diaries of Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn. More darkly, the Puritan Regicides who had beheaded Charles’s father were hung, drawn and quartered along with Cromwell’s exhumed corpse.

The Libertarianism ushered in by the Restoration had a much longer run than the initial rule of Puritanism had enjoyed. It lasted through the Georgian Age of the 18th century, culminating in the decadence of the Regency bucks and Queen Victoria’s “wicked uncles”. Puritanism made its comeback with the accession of Victoria herself, with her eponymous reign infamous for its crinolines, covered piano legs, cruel persecution of that supreme Libertarian Oscar Wilde, and its massive hypocrisy – a constant adjunct of Puritanism when it comes up against the incontrovertible facts of life and human nature.

Neatly coinciding with the reign of Victoria’s despised eldest son, Libertarianism returned in the portly shape of Edward VII in the opening decade of the 20th century to which he gave his name. As during the Restoration, the ruling elite again set the tone of the Edwardian era with their shooting and hunting, their discreet adultery at country house weekends, and their lavish clubs and parties.

July 8, 2020

Harry Potter fandom, Millennials, and the continued decline of traditional religious beliefs

In The Critic, Oliver Wiseman talks to Tara Isabella Burton about her book Strange Rites:

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books have been pivotal for many Millennials in encouraging them to move away from traditional religious beliefs.

I want to start with Harry Potter, which is — perhaps surprisingly — central to the argument you make in the book, so, as an introduction to your broader thesis, what does Harry Potter have to do with America’s new religions?

It’s funny. When Harry Potter first came out in the nineties, there was a flurry American Christian voices saying “This book promotes witchcraft. There’s going to be a whole new religious movement devoted to Harry Potter books.” In the way they meant it, that was absolutely not true. But I think that there was something to it in terms of an inadvertent change to the religious landscape.

What Harry Potter did, or, more accurately, what it was the canary in the coal mine for, was a transformation, linked to the rise of at-home internet access, in how we talk about cultural properties andhow we relate to cultural properties. The transition to an internet space defined by user-generated content and what is often called participatory culture coincided with the publication of the Harry Potter books.

Between the first Harry Potter book’s release in 1997 and the fourth book’s publication in 2000 we went from 19 million Americans with internet access to more than 100 million. It’s that backdrop that really explains the shift. You did have fan cultures before. There were Star Wars conventions, for example, but there was quite a high bar to entry. You had to get on the right mailing list and it was done via post. It was quite a lot of work. You couldn’t just log on and enter a community, which is really what could happen with Harry Potter fandom.

J.K. Rowling was also one of the first major writers to openly accept and embrace fan fiction. So what you ended up seeing was something that started with Harry Potter fandom that then became an element of fandom online more broadly which in turn, I would argue, shaped millennial-and-younger culture. It was this idea that you weren’t just a reader of consumer of texts. It wasn’t just a top down hierarchical thing. Instead, mediated through the anonymity of the internet, you a kind of tribalism from talking to people in different geographical areas as well as things like fan fiction and later meme culture that meant you could change, shift, reimagine a text in your own way. And what’s so interesting about that is that sensibility — the sensibility that we have not only the right but the responsibility, the authority as consumers to also be creators, to rework ideas outside of existing texts — has spilled over into all aspects of our political life and of our religious life. And that is really something that is the product of user generated content and the internet.

To bring this to religion more specifically, 36 per cent of Americans born after 1985 are religiously unaffiliated, compared to about 23 per cent of the national average. That’s a huge generational shift in religious affiliation and organisation. That is not the same thing as saying that these are atheists or that these people are not religious. Some 72 per cent of them say they believe in some sort of higher power. About 17 per cent say they believe in the Judaeo-Christian God.

We’re in a religious or spiritual landscape that privileges mixing and matching, and unbundling — a bit of tarot here, a bit of meditation there. And a resistance to institutional and authoritative declarations in terms of how religion should be practised is very much something that has its roots in internet culture, of which Harry Potter was a forerunner.

July 5, 2020

July 3, 2020

June 28, 2020

QotD: Nietzsche’s views on Christianity

Nietzsche was a devastating critic of dogmatic Christianity — Christianity as it was instantiated in institutions. Although, he is a very paradoxical thinker. One of the things Nietzsche said was that he didn’t believe the scientific revolution would have ever got off the ground if it hadn’t been for Christianity and, more specifically, for Catholicism. He believed that, over the course of a thousand years, the European mind had to train itself to interpret everything that was known within a single coherent framework — coherent if you accept the initial axioms. Nietzsche believed that the Catholicization of the phenomena of life and history produced the kind of mind that was then capable of transcending its dogmatic foundations and concentrating on something else. In this particular case it happened to be the natural world.

Nietzsche believed that Christianity died of its own hand, and that it spent a very long time trying to attune people to the necessity of the truth, absent the corruption and all that — that’s always part of any human endeavour. The truth, the spirit of truth, that was developed by Christianity turned on the roots of Christianity. Everyone woke up and said, or thought, something like, how is it that we came to believe any of this? It’s like waking up one day and noting that you really don’t know why you put a Christmas tree up, but you’ve been doing it for a long time and that’s what people do. There are reasons Christmas trees came about. The ritual lasts long after the reasons have been forgotten.

Nietzsche was a critic of Christianity and also a champion of its disciplinary capacity. The other thing that Nietzsche believed was that it was not possible to be free unless you had been a slave. By that he meant that you don’t go from childhood to full-fledged adult individuality; you go from child to a state of discipline, which you might think is akin to self-imposed slavery. That would be the best scenario, where you have to discipline yourself to become something specific before you might be able to reattain the generality you had as a child. He believed that Christianity had played that role for Western civilization. But, in the late 1800s, he announced that God was dead. You often hear of that as something triumphant but for Nietzsche it wasn’t. He was too nuanced a thinker to be that simpleminded. Nietzsche understood — and this is something I’m going to try to make clear — that there’s a very large amount that we don’t know about the structure of experience, that we don’t know about reality, and we have our articulated representations of the world. Outside of that there are things we know absolutely nothing about. There’s a buffer between them, and those are things we sort of know something about. But we don’t know them in an articulated way.

Jordan B. Peterson, “Biblical Series I: Introduction to the Idea of God” {transcript], jordanbpeterson.com, 2018-03-12.