If many among the people loved him, then this was in part because Nero had offered them the chance to share in his conflation of the heavenly with the earthly. In the wake of the great fire that, in 64, had destroyed much of Rome, he had planted a park in the very centre of the city. The sprawling lawns, lakes and forests that surrounded what he termed his “Golden House” had offered to the masses a feel of fresh breezes, a break from the monotony of smoke and brick, a hint of the pavilions of the immortals on Mount Olympus.

Senators, of course, had hated it. The loss of Rome’s familiar sights to countryside had borne witness precisely to what they had always found most disorienting about Nero: his ability to dissolve the boundaries of everything that they had previously taken for granted. So it was that they had accused him of starting the fire deliberately, as a way of clearing a space for his building plans; and so it was that Nero, looking to shift the blame, had fixed on convenient scapegoats. These culprits, even by Nero’s own taboo-busting standards, embodied everything that decent citizens had always most dreaded about moral upheaval: the adherents of a sinister cult whose motivation was nothing less than, in the words of a Roman historian, “their hatred for the norms of human society”.

“Christians”, these deviants were called, after their founder, “Christus”, a criminal who had been crucified in Judaea some decades before, under a previous Caesar. Nero, ever fond of a spectacle, had displayed a vengefulness worthy of the Olympian gods. Some of the condemned, dressed in animal skins, had been torn to pieces by dogs. Others, lashed to crosses, had been smeared in pitch and used as torches to illumine the night. Nero, riding in his chariot, had mingled with the gawping crowds. Suetonius would include his persecution of the Christians in the list — a very short one — of the positives of his reign.

Among those put to death, so later tradition would record, was a man who in time would come to be viewed as the very keeper of the doors of heaven. In 1601, in a church that had originally been built on the site of the tomb where Nero’s two nurses and his first great love had buried him, a painting was installed that paid homage, not to the notorious Caesar, but to the outcast origins of the city’s Christian order.

The artist, a young man from Milan by the name of Caravaggio, had been commissioned to portray a crucifixion: not of Christ himself, but of his leading disciple. Peter, a fisherman who, according to the Gospels, had abandoned his boat and nets to follow Jesus, was said to have become the bishop of the very first Christians of Rome. Since his execution in the wake of the great fire, more than 200 men had held the bishopric: an office which brought with it a claim to primacy over the entire Church, and the honorary title of “Pappas” or “Father” — “Pope”.

Tom Holland, “When Christ conquered Caesar”, UnHerd, 2020-04-10.

April 4, 2025

QotD: Nero’s persecution of the early Christians

March 6, 2025

Passionate belief in historical untruths

As mentioned in earlier posts, one of the most toxic exports from Australia to the rest of the Anglosphere has been the academic indulgence in believing that “settler colonialism” explains everything about the history of Canada, Australia, New Zealand and anywhere else the British diaspora touched:

Throughout the English-speaking world elites are falling over themselves to believe the very worst of their own countries.

In Britain, the Church of England has committed itself to spend an initial £100 million on slavery-reparations in response to the discovery that its endowment had “links” with African enslavement. “The immense wealth accrued by the Church … has always been interwoven with the history of African chattel enslavement”, a document explains. “African chattel enslavement was central to the growth of the British economy of the 18th and 19th centuries and the nation’s wealth thereafter”. And this has “continuing toxic consequences”.

Yet almost none of this is true. The evidence shows that the Church’s endowment fund was hardly involved in the evil of slave-trading at all. Most economic historians reckon the contribution of slave-trading and slavery to Britain’s economic development as somewhere between marginal and modest. And between abolition in 1834 and the present, multiple causes have intervened to diminish slavery’s effects.

Consonant with his church’s policy, the (then) Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby preached a sermon in Christ Church Cathedral, Zanzibar last year, in which he criticised Christian missionaries for treating Africans as inferior and confessed that “we [British] must repent and look at what we did in Zanzibar”.

Really? What the British did in Zanzibar during the second half of the 19th century was to force the Sultan to end the slave-trade. Indeed, the cathedral in which the archbishop was preaching was built over the former slave-market. And here’s what the pioneering missionary David Livingstone wrote about black Africans in 1871: “I have no prejudice against [the Africans’] colour; indeed, anyone who lives long among them forgets they are black and feels that they are just fellow men…. If a comparison were instituted, … I should like to take my place among [them], on the principle of preferring the company of my betters”.

[…]

St. John Baptiste church was one of many local churches to go up in flames during Justin Trudeau’s performative national guilt trip over “unmarked mass graves” at former Residential Schools across Canada.

Which bring us to Canada. The May 2021 claim by a Kamloops Indian band to have discovered the remains of 215 “missing children” of an Indian Residential School was quickly sexed up by the media into a story ‘mass graves’, with all its connotation of murderous atrocity. The Toronto Globe and Mail published an article under the title, “The discovery of a mass gravesite at a former residential school in Kamloops is just the tip of the iceberg”, in which a professor of law at UBC wrote: “It is horrific … a too-common unearthing of the legacy, and enduring reality, of colonialism in Canada”. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ordered Canadian flags to be flown at half-mast on all federal buildings to honour the murdered children. Because the Kamloops school had been run by Roman Catholics, some zealous citizens took to burning and vandalising churches, 112 of them to date. The dreadful tale was eagerly broadcast worldwide by Al Jazeera.

Yet, four years later, not a single set of remains of a murdered Indian child in an unmarked grave has been found anywhere in Canada. Judging by the evidence collected by Chris Champion and Tom Flanagan in their best-selling 2023 book, Grave Error: How the Media Misled us (and the Truth about the Residential Schools), it looks increasingly probable that the whole, incendiary story is a myth.

So, prime ministers, archbishops, academics, editors, and public broadcasters are all in the business of exaggerating the colonial sins of their own countries against noble (not-so-very) savages — from London to Sydney to Toronto. Why?

March 5, 2025

QotD: British and French Enlightenments

In 2005, [Gertrude Himmelfarb] published The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. It is a provocative revision of the typical story of the intellectual era of the late eighteenth century that made the modern world. In particular, it explains the source of the fundamental division that still doggedly grips Western political life: that between Left and Right, or progressives and conservatives. From the outset, each side had its own philosophical assumptions and its own view of the human condition. Roads to Modernity shows why one of these sides has generated a steady progeny of historical successes while its rival has consistently lurched from one disaster to the next.

By the time she wrote, a number of historians had accepted that the Enlightenment, once characterized as the “Age of Reason”, came in two versions, the radical and the skeptical. The former was identified with France, the latter with Scotland. Historians of the period also acknowledged that the anti-clericalism that obsessed the French philosophes was not reciprocated in Britain or America. Indeed, in both the latter countries many Enlightenment concepts — human rights, liberty, equality, tolerance, science, progress — complemented rather than opposed church thinking.

Himmelfarb joined this revisionist process and accelerated its pace dramatically. She argued that, central though many Scots were to the movement, there were also so many original English contributors that a more accurate name than the “Scottish Enlightenment” would be the “British Enlightenment”.

Moreover, unlike the French who elevated reason to a primary role in human affairs, British thinkers gave reason a secondary, instrumental role. In Britain it was virtue that trumped all other qualities. This was not personal virtue but the “social virtues” — compassion, benevolence, sympathy — which British philosophers believed naturally, instinctively, and habitually bound people to one another. This amounted to a moral reformation.

In making her case, Himmelfarb included people in the British Enlightenment who until then had been assumed to be part of the Counter-Enlightenment, especially John Wesley and Edmund Burke. She assigned prominent roles to the social movements of Methodism and Evangelical philanthropy. Despite the fact that the American colonists rebelled from Britain to found a republic, Himmelfarb demonstrated how very close they were to the British Enlightenment and how distant from French republicans.

In France, the ideology of reason challenged not only religion and the church, but also all the institutions dependent upon them. Reason was inherently subversive. But British moral philosophy was reformist rather than radical, respectful of both the past and present, even while looking forward to a more enlightened future. It was optimistic and had no quarrel with religion, which was why in both Britain and the United States, the church itself could become a principal source for the spread of enlightened ideas.

In Britain, the elevation of the social virtues derived from both academic philosophy and religious practice. In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith, the professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow University, was more celebrated for his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) than for his later thesis about the wealth of nations. He argued that sympathy and benevolence were moral virtues that sprang directly from the human condition. In being virtuous, especially towards those who could not help themselves, man rewarded himself by fulfilling his human nature.

Edmund Burke began public life as a disciple of Smith. He wrote an early pamphlet on scarcity which endorsed Smith’s laissez-faire approach as the best way to serve not only economic activity in general but the lower orders in particular. His Counter-Enlightenment status is usually assigned for his critique of the French Revolution, but Burke was at the same time a supporter of American independence. While his own government was pursuing its military campaign in America, Burke was urging it to respect the liberty of both Americans and Englishmen.

Some historians have been led by this apparent paradox to claim that at different stages of his life there were two different Edmund Burkes, one liberal and the other conservative. Himmelfarb disagreed. She argued that his views were always consistent with the ideas about moral virtue that permeated the whole of the British Enlightenment. Indeed, Burke took this philosophy a step further by making the “sentiments, manners, and moral opinion” of the people the basis not only of social relations but also of politics.

Keith Windschuttle, “Gertrude Himmelfarb and the Enlightenment”, New Criterion, 2020-02.

February 26, 2025

Colonialism was so bad … that we have to make shit up about how evil it supposedly was

In the National Post, Nigel Biggar recounts some of the most egregious virtue signalling by western elites over the claimed evils of colonialism … even to the point of inventing sins to confess and obsess over:

Meanwhile, in Australia, there’s the extraordinary career of Bruce Pascoe’s 2014 book, Dark Emu. This argues that Aborigines, far from being primitive nomads, developed the first egalitarian society, invented democracy, and were sophisticated agriculturalists. Such was the morally superior civilization that white colonizers trashed in their racist greed. Named Book of the Year, Dark Emu has sold more than 360,000 copies and was made the subject of an Australian Broadcasting Company documentary.

Yet, it has been widely criticized for being factually untrue. Author Peter O’Brien has forensically dismantled it in Bitter Harvest: The Illusion of Aboriginal Agriculture in Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu (2020). And in Farmers or Hunter Gatherers: The Dark Emu Debate (2021) — described by reviewers as “rigorously researched”, “masterful”, and “measured” — eminent anthropologist Peter Sutton and archaeologist Keryn Walshe dismiss Pascoe’s claims.

Which bring us to Canada. The May 2021 claim by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation to have discovered the “remains of 215 children” of an Indian Residential School was quickly sexed up by the media into a story about a “mass grave”, with all its connotation of murderous atrocity. The Globe and Mail published an article under the title, “The discovery of a mass gravesite at a former residential school in Kamloops is just the tip of the iceberg,” in which a professor of law at UBC wrote: “It is horrific … a too-common unearthing of the legacy, and enduring reality, of colonialism in Canada”. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ordered Canadian flags to be flown at half-mast on all federal buildings to honour the allegedly murdered children. Because the Kamloops school had been run by Roman Catholics, some zealous citizens took to burning and vandalizing churches, 112 of them to date. The dreadful tale was eagerly broadcast worldwide by Al Jazeera.

Yet, almost four years later, not a single set of remains of a murdered Indigenous child in an unmarked grave has been found anywhere in Canada. Judging by the evidence collected by Chris Champion and Tom Flanagan in their best-selling 2023 book, Grave Error: How the Media Misled us (and the Truth about the Residential Schools), it looks increasingly probable that the whole, incendiary story is a myth.

So, prime ministers, archbishops, academics, editors, and public broadcasters are all in the business of exaggerating the colonial sins of their own countries — from London to Sydney to Toronto. Why?

An obvious reason is the well-meaning desire to raise respect for indigenous cultures with a view to “healing” race relations. But that doesn’t explain the aggressive brushing aside of concerns about evidence and truth in the eager rush to irrational self-criticism.

February 16, 2025

Pope Fights: The Pornocracy – Yes it’s really called that

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 25 Oct 2024Guard your browsing histories, the Popes are at it again …

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Rome: A History in Seven Sackings by Matt Kneale

Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy by John Julius Norwich

Antapodosis by Liutprand of Cremona

A. Burt Horsley, “Pontiffs, Palaces and Pornocracy — A Godless Age”, in Peter and the Popes (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 65–78.

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Henry VIII, Lady Killer – History Hijinks

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 3 Feb 2023brb I’m blaring “Haus of Holbein” from Six the Musical on the loudest speakers I own.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Britannica “Henry VIII” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/…, History “Who Were The Six Wives of Henry VIII” (https://www.history.com/news/henry-vi…), The Great Courses lectures: “Young King Hal – 1509-27”, “The King’s Great Matter – 1527-30”, “The Break From Rome – 1529-36”, “A Tudor Revolution – 1536-47”, and “The Last Years of Henry VIII – 1540-47” from A History of England from the Tudors to the Stuarts by Robert Bucholz

(more…)

February 12, 2025

Did Medieval People Eat Breakfast?

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 1 Oct 2024Toasted white bread with sweet spices, white wine, and thick homemade almond milk

City/Region: England

Time Period: c. 1450Some medieval people ate breakfast sometimes. It depended on things like your social status and job, your age, and what part of the Middle Ages it was. Bread, cheese, and ale were common breakfast items, and sops are mentioned in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. There are a lot of variations of sops, but essentially it’s toast that’s soaked in some kind of flavorful liquid like wine or ale.

This recipe for golden sops uses white bread that is soaked in white wine and topped with almond milk that has been simmered until it resembles a thin custard. I was worried that the wine would dominate the flavor, but it doesn’t. What comes through most are the warm spices and light sweetness that remind me of Cinnamon Toast Crunch. Delicious.

Soppes Dorre.

Take rawe Almondes, And grynde hem in A morter, And temper hem with wyn and drawe hem throgh a streynour; And lete hem boyle, And cast there-to Saffron, Sugur, and salt; And then take a paynmain, And kut him and tost him, And wte him in wyne, And ley hem in a dissh, and caste the siryppe thereon, and make a dregge of pouder ginger, sugur, Canell, Clowes, and maces, And cast thereon; And whan hit is I-Dressed, serue it forth fore a good pottage.

— Harleian MS. 4016, c. 1450

February 6, 2025

January 14, 2025

QotD: Ritual in medieval daily life

I am not in fact claiming that medieval Catholicism was mere ritual, but let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that it was — that so long as you bought your indulgences and gave your mite to the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever and showed up and stayed awake every Sunday as the priest blathered incomprehensible Latin at you, your salvation was assured, no matter how big a reprobate you might be in your “private” life. Despite it all, there are two enormous advantages to this system:

First, n.b. that “private” is in quotation marks up there. Medieval men didn’t have private lives as we’d understand them. Indeed, I’ve heard it argued by cultural anthropology types that medieval men didn’t think of themselves as individuals at all, and while I’m in no position to judge all the evidence, it seems to accord with some of the most baffling-to-us aspects of medieval behavior. Consider a world in which a tag like “red-haired John” was sufficient to name a man for all practical purposes, and in which even literate men didn’t spell their own names the same way twice in the same letter. Perhaps this indicates a rock-solid sense of individuality, but I’d argue the opposite — it doesn’t matter what the marks on the paper are, or that there’s another guy named John in the same village with red hair. That person is so enmeshed in the life of his community — family, clan, parish, the Sacred Confraternity of the Holy Whatever — that “he” doesn’t really exist without them.

Should he find himself away from his village — maybe he’s the lone survivor of the Black Death — then he’d happily become someone completely different. The new community in which he found himself might start out as “a valley full of solitary cowboys”, as the old Stephen Leacock joke went — they were all lone survivors of the Plague — but pretty soon they’d enmesh themselves into a real community, and red-haired John would cease to be red-haired John. He’d probably literally forget it, because it doesn’t matter — now he’s “John the Blacksmith” or whatever. Since so many of our problems stem from aggressive, indeed overweening, assertions of individuality, a return to public ritual life would go a long way to fixing them.

The second huge advantage, tied to the first, is that community ritual life is objective. Maybe there was such a thing as “private life” in a medieval village, and maybe “red-haired John” really was a reprobate in his, but nonetheless, red-haired John performed all his communal functions — the ones that kept the community vital, and often quite literally alive — perfectly. You know exactly who is failing to hold up his end in a medieval village, and can censure him for it, objectively — either you’re at mass or you’re not; either you paid your tithe or you didn’t; and since the sacrament of “confession” took place in the open air — Cardinal Borromeo’s confessional box being an integral part of the Counter-Reformation — everyone knew how well you performed, or didn’t, in whatever “private” life you had.

Take all that away, and you’ve got process guys who feel it’s their sacred duty — as in, necessary for their own souls’ sake — to infer what’s going on in yours. Strip away the public ritual, and now you have to find some other way to make everyone’s private business public … I don’t think it’s unfair to say that Calvinism is really Karen-ism, and if it IS unfair, I don’t care, because fuck Calvin, the world would’ve been a much better place had he been strangled in his crib.

A man is only as good as the public performance of his public duties. And, crucially, he’s no worse than that, either. Since process guys will always pervert the process in the name of more efficiently reaching the outcome, process guys must always be kept on the shortest leash. Send them down to the countryside periodically to reconnect with the laboring masses …

Severian, “Faith vs. Works”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2021-09-07.

January 12, 2025

Quebec within the British Empire after 1760

Fortissax, in response to a question about the historical situation of Quebec within Canada, outlines the history from before the Seven Years’ War (aka the “French and Indian War” to Americans) through the American Revolution, the 1837-38 rebellions, the Durham Report, and Confederation:

First and foremost, Canada itself, as a state — an administrative body, if you will — was originally founded by France. Jacques Cartier named the region in 1535, and Samuel de Champlain established the first permanent French settlement in North America in Quebec City in 1608. This settlement would become the largest and most populous administrative hub for the entire territory. Canada was a colony within the broader territory of New France, which stretched from as far north as Tadoussac all the way down to Louisiana. It included multiple hereditary land-owning noblemen of Norman extraction.

During the Seven Years’ War, on 8 September 1760, General Lévis and Pierre de Vaudreuil surrendered the colony of Canada to the British after the capitulation of Montreal. Though the British had effectively won the war, the Conquest’s details still had to be negotiated between Great Britain and France. In the interim, the region was placed under a military regime. As per the Old World’s “rules of war”, Britain assured the 60,000 to 70,000 French inhabitants freedom from deportation and confiscation of property, freedom of religion, the right to migrate to France, and equal treatment in the fur trade. These assurances were formalized in the 55 Articles of the Capitulation of Montreal, which granted most of the French demands, including the rights to practice Roman Catholicism, protections for Seigneurs and clergymen, and amnesty for soldiers. Indigenous allies of the French were also assured that their rights and privileges would be respected.

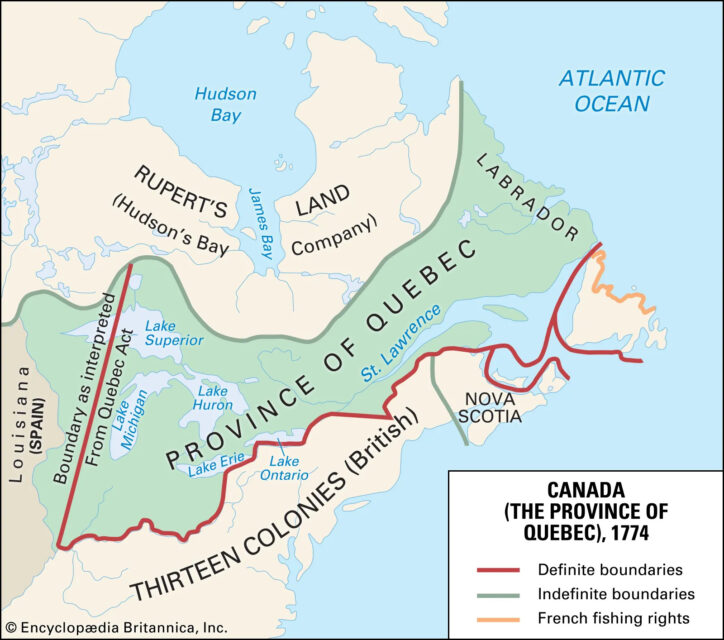

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 officially ended the war and renamed the French colony of “Canada” as “the Province of Quebec”. Initially, its borders included parts of present-day Ontario and Michigan. To address growing tensions between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies and to maintain peace in Quebec, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act in 1774. This act solidified the French-speaking Catholic population’s rights, such as the free practice of Catholicism, restoration of French civil law, and exemption from oaths referencing Protestant Christianity. These provisions satisfied the Québécois Seigneurs (land-owning nobleman), and clergy by preserving their traditional rights and influence. However, some Anglo settlers in America resented the Act, viewing it as favoring the French Catholic majority. Despite this, the Act helped maintain stability in Quebec, ensuring it remained loyal to Britain during the American Revolutionary War and Quebec was fiercely opposed to liberal French revolutionaries.

British concessions, from the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris to the Quebec Act of 1774, safeguarded the cultural and religious identity of Quebec’s French-speaking Catholic population, fostering their loyalty during a period of significant upheaval in North America. Following this period, merchant families such as the Molsons began establishing themselves in Montreal, alongside early Loyalist settlers who trickled into areas now known as the Eastern Townships. These merchant families quickly ingratiated themselves with the local Norman lords and seigneurs.

The Lower Canada Rebellion arose in 1837-1838 due to the Château Clique oligarchy (an alliance of Anglo-Scottish industrialists and French noble landowners), in Quebec refusing to grant legislative power to the French Canadian majority. The rebellion was not solely a French Canadian effort; to the chagrin of both chauvinistic Anglo-Canadians and French Canadians, who in recent years believed it was either a brutal crackdown on French degeneracy, or a heroic class struggle of French peasants against an oppressive Anglo elite. It included figures like Wolfred Nelson, an Anglo-Quebecer who personally led troops into battle.

In response to the unrest following the rebellions of 1837-1838, Lord Durham, a British noble, was sent to Canada to investigate and propose solutions. His controversial recommendation, outlined in the Durham Report of 1839, was to abolish the separate legislatures of Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec) and merge them into a single entity: the Province of Canada. This unification aimed to demographically and culturally assimilate the French Canadian population by creating an English-speaking majority.

However, the strategy failed for multiple reasons, and was given up shortly after. Lord Durham, having neither been born nor raised in the New World, underestimated the complexities of Canadian society, which was a unique fusion of Old World ideas in a New World setting. His assumption that French Canadians could be assimilated ignored their strong cultural identity, rooted in large families, which encouraged high birth rates as a means of survival. While Durham hoped unification would erode divisions, the old grievances between the British and French began to dissipate naturally.

Despite Lord Durham’s intentions, French Canadians maintained their dominance in Quebec. Families averaged five children per household for over 230 years, a trend actively encouraged by the Catholic Church’s policy of La Revanche des Berceaux (the Revenge of the Cradles). This strategy aimed to preserve French Canadian culture and identity amidst the British short-lived attempts at assimilation. In Montreal, British industrialists expanded their influence by forging alliances with French landowning nobles through business partnerships and intermarriage. This blending of elites produced a bilingual Anglo-French upper class that became historically influential.

Such alliances drew on long-standing connections established as early as 1763 and later exemplified by the North West Company (NWC). The NWC in particular is interesting as a prominent fur trading enterprise of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in that it embodied this fusion of cultures. Led primarily by Anglo-Scots, the company’s leaders frequently formed unions or marriages with French Canadian women, fostering vital ties with the French Canadian communities crucial to their trade. Simon McTavish, known as the “father” of the NWC, maintained alliances with French Canadian families, while his nephew, William McGillivray, and other leaders like Duncan McGillivray followed similar paths. Explorers such as Alexander MacKenzie and David Thompson married French women. These unions strengthened familial and cultural bonds, shaping the broader Anglo-French collaboration that defined this period.

This relative harmony between Anglo and French Canadians continued with the formation of the modern Canadian state in 1867 during Confederation. Sir John A. Macdonald deliberately chose George-Étienne Cartier as his second-in-command. This collaboration contributed to the emergence of Canada’s ethnically Anglo-French elite, who have historically been bilingual. This legacy is evident in the backgrounds of many Canadian politicians, such as the Trudeaus, Mulroneys, Martins, Cartiers, and countless others who have both Anglo-Canadian and French-Canadian roots.

In more recent history, this dynamic has been further solidified by the federal government, where higher-paid positions often require bilingual proficiency. Interestingly, about 20% of Canada’s population is bilingual, reflecting the ongoing influence of this historical coexistence.

The last cannon which is shot on this continent in defence of Great Britain will be fired by the hand of a French Canadian.

~ George Etienne Cartier

December 25, 2024

QotD: Divine will

It is only the savage, whether of the African bush or of the American gospel tent, who pretends to know the will and intent of God exactly and completely.

H.L. Mencken, Damn! A Book of Calumny, 1918.

December 22, 2024

Canada’s founding peoples

Fortissax contrasts Canadians and Americans ethnically, culturally, and historically. Here he discusses Anglo-Canadians and French-Canadians:

To understand Canada, you must first understand its foundations.

Canada is a breakaway society from the United States, like the United States was a breakaway society from the British Empire. You might even argue that Britain represented a thesis, America an antithesis, and Canada the synthesis.

Anglo-Canadians

Anglo-Canadians are descendants of the Loyalists from the American Revolution. They were North Americans, not British transplants, as depicted in American propaganda like Mel Gibson’s The Patriot. They shared the same pioneering and independent spirit as their Patriot counterparts. All were English “Yeoman” or free men. American history from the Mayflower to 1776 is also Canadian history. It is why both nations share Thanksgiving. Some historians have identified the American Revolution as an English civil war, and this is a fairly accurate assessment.

The United States’ founding philosophy was rooted in liberalism; it is a proposition nation based on creed over blood, shaped by Enlightenment thinkers like Edmund Burke and John Locke, now considered “conservative”. American revolutionaries embraced ideals of meritocracy, individualism, property rights, capitalism, free enterprise, republicanism, and democracy, which empowered the emerging middle class.

Anglo-Canada’s founding philosophy is British Toryism, emerging as a traditionalist and reactionary force in direct response to the American Revolution. During the revolution, many Loyalists had their private property seized or redistributed, suffered beatings in the streets, and in the worst cases, faced public executions or the infamous punishment of tar and feathering. Canadian philosopher George Grant, who is considered the father of Anglo-Canadian nationalism, traced their roots to Elizabethan-era Anglican theologian Richard Hooker.

Canada’s motto, Peace, Order, and Good Government (POGG), reflects a philosophy in stark contrast to the American ideal of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Anglo-Canadians valued God, King, and Country, emphasizing public morality, the common good, and Tory virtues like noblesse oblige — the expectation and obligation of elites to act benevolently within an organic hierarchy. While liberty was important, it was never to come at the expense of order. Canadian conservatism before the 1960s was not a variation of liberalism, as in the U.S., but a much older, European, and genuinely traditional ideology focused on community, public order, self-restraint, and loyalty to the state — values embedded in Canada’s founding documents.

Section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, empowers Parliament to legislate for the “peace, order, and good government” of Canada, giving rise to Crown corporations like Ontario Hydro, the CBC, and Canadian National Railway — state-owned enterprises. Canada’s tradition of mixed economic policies is often misunderstood by Americans as socialism, communism, or totalitarianism. These state-owned enterprises have historical precedents, such as state-controlled factories during Europe’s industrial revolution, often run by landed nobility. Going further back, state-owned mines in ancient Athens and Roman Empire granaries also exemplify this model, which cannot be simplistically labeled as “Islamofascist communism” — a mischaracterization of anything not aligned with liberalism by many Americans, and increasingly many populist Canadians.

It is also a lesser-known historical fact that Canada was almost ennobled into a kingdom rather than a dominion. This idea was suggested by Thomas D’Arcy McGee, a prominent Irish-Canadian politician, journalist, and one of the Fathers of Confederation. Deeply involved in the creation of Canada as a nation, McGee proposed in the 1860s that Canada could be formed as a monarchy with a hereditary nobility, possibly with a viceroyal king, likely a son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He believed this would provide stability and continuity to the fledgling nation. While this idea was not realized, its influence can be seen in the entrenched elites of Canada, who, in a sense, became an unofficial aristocracy.

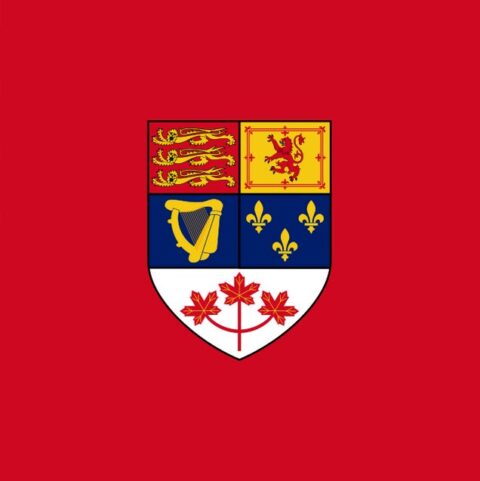

An element of Canada’s conservative origins can also be found in its use of traditional British and French heraldry. Every province, for example, has a medieval-style coat of arms, often displayed on its flag, which reinforces this connection to the old-world traditions McGee sought to preserve.

McGee’s vision was rooted in his belief in the importance of monarchical institutions and his desire to strengthen Canada’s bond with the British Crown while fostering a distinct Canadian identity. He argued that ennobling Canada would give the country legitimacy and elevate it in the eyes of Europe and the wider world.

French-Canadians

French Canada, with Quebec as its largest and most influential component, has a distinct history shaped by its French colonial roots. Quebec was primarily settled by French colonists, and its unique culture and identity have evolved over the centuries, heavily influenced by Catholicism and monarchical traditions.

The Jesuits and other Catholic organizations played a pivotal role in shaping early French Canadian society. They not only spread Christianity but also laid the foundation for Quebec’s social and cultural identity. The Jesuits, part of the Society of Jesus, were among the first Catholic missionaries to arrive in New France. Invited by Samuel de Champlain, the founder of Quebec, in 1611, they helped convert Indigenous populations to Catholicism but often remained separate from them. By 1625, they had established missions among various Indigenous nations, including the Huron, Algonquin, and Iroquois.

Unlike France, Quebec bypassed the upheavals of the French Revolution and the Reign of Terror. Isolated from the homeland, the Catholic Church in Quebec consolidated its power, and French colonists faced the threat of extinction due to their initially low numbers, particularly during the one-hundred-year war with the Iroquois. This struggle only strengthened their resolve. Over time, this foundation gave rise to Clerico-Nationalism, particularly exemplified by figures like Abbé Lionel Groulx, a theocratic monarchist and ultramontanist influenced by anti-liberal Catholic nationalist movements in France. Groulx and his contemporaries emphasized loyalty to the Pope over secular governments, and their influence was so strong that the Union Nationale government of Maurice Duplessis embodied many of their beliefs.

Attempts to secularize education in the 1860s were thwarted, as the Catholic theocracy shut them down and restored control to the Church. Quebec remained a theocracy well into the 20th century, with the Catholic Church controlling public schooling and provincial healthcare until the 1960s. For much of its history, Quebecois culture saw itself as the last bastion of the traditionalist, Catholic, monarchist Ancien Régime of the fallen Bourbon monarchy. Liberal republicanism and the French Revolution were regarded as abominations, and French-Canadians believed they were the true French.

This mindset persists today, especially regarding Quebecois French. The 400-year-old dialect, rooted in Norman French and royal court French, is still regarded by many French-Canadians as “true French”. However, Europeans often deny this claim, pointing out the influence of anglicisms and the use of joual, a working-class dialect that was deliberately encouraged by Marxist intellectuals and separatists during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s to proletarianize the population.

December 19, 2024

“A decree went out from Caesar Augustus” – The evidence for the date of the birth of Jesus

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 18 Dec 2024It’s December, with Christmas fast approaching, and I suspect that a fair few people who never think much about the Romans will hear mention of Caesar Augustus because of this verse from Luke’s Gospel. I have an appendix about this in my biography of Augustus, so thought that I would talk about how the New Testament dates the Christmas story and how well this fits with our other sources for the Ancient World.

December 8, 2024

The potential for retribution in a second Trump presidency

Francis Christian meditates on whether or how President-elect Donald Trump will indulge in eye-for-an-eye revenge against the individuals most clearly involved in the lawfare and other attempts to derail his re-election:

It was the English poet Alexander Pope who admonished us in the manner of the New Testament that “to err is human; to forgive, divine” — Errare humanum est, ignoscere divino.

The Old Testament in contrast, has the equally familiar and perhaps far more popular, “eye for an eye“, and in one of the most revolutionary statements ever uttered, Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount talked about us “having heard that it was said, ‘an eye for an eye’ — but I say unto you, love your enemies“.

To wish to take revenge upon one’s enemies is therefore human, but Jesus is asking mankind to rise above this basic instinct and instead, to forgive and love one’s enemies. This was all of course part of His Mission on earth — to change by His Life, His Cross and the Resurrection, the destiny of human beings from being bound to basic instincts and death — to being bound for eternal life, a different destiny and a new creation.

The mavens of Hollywood of course march to a different and more ancient tune (which has been handed down unchanged to them) and generations of movie goers and consumers of media have been brought up on the idea that revenge of the most explosively visceral kind is a good thing, even a noble thing.

My readers will undoubtedly have their own sincerely held beliefs about Jesus’ command to love our enemies and to do good to those who hate us and once again, I do not wish this essay to turn out to be a sermon! What I wish to address instead, is to ask the question: what is the place for retribution, vengeance and revenge in the conduct of statecraft?

In other words, when President elect Trump said in a recently widely publicized interview that he was, “not looking for retribution, grandstanding or to destroy people who treated me very unfairly“, was he declaring a principle of statecraft that makes for a fulfilling and productive Presidency? And is this also a principle of statecraft that will “make American great again?”

In typical, inimitable and endearing Trumpian fashion, the President-elect also added the tongue in cheek comment: “I am always looking to give a second and even third chance, but never willing to give a fourth chance — that is where I hold the line!”

It could be argued from the life of no less a colossal figure than Julius Caesar that decisive and devastating revenge upon one’s enemies makes for a strong and respected ruler and nation. Whilst still a private citizen, Julius Caesar was captured by pirates on the way to the Greek island of Rhodes (to which he was travelling in order to learn oratory from the famous professor Molon). Caesar raised his own ransom — then raised a naval force, captured his pirate captors and had them all crucified.

The later assassination of Caesar and the subsequent civil wars that rocked and roiled Rome is the subject of Shakespeare’s magnificent, Tragedy of Julius Caesar. The subsequent rule of Augustus Caesar was marked by stability, expansion of the empire, the building of roads and bridges (via which the Gospel was to travel), the making of sea and land routes safe for travellers (again, to the advantage of the early Christians taking the Gospel to Asia and Europe) the consolidation of Roman power — and the rule of (Roman) law. It was also during the reign of this austere, learned emperor that Jesus was born in a manger, in the Roman province of Palestine.

H/T to Brian Peckford for the link.

QotD: Who invented the vending machine?

This one surprised me: the vending machine was invented not for Coca-Cola or cigarettes or snack foods, but for books.

Richard Carlile was a shit-disturbing English bookseller. He insisted on selling Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason despite it being seditious and blasphemous for its attacks on organized religion, particularly the Church of England. Impressively stubborn, Carlile was arrested in 1819, imprisoned, and fined a massive £1,500 for selling Paine’s work. While a guest of the state, his wife, Jane, and other associates kept selling The Age of Reason, leading to more arrests.

Sometime around his release in 1822, Carlile came up with the idea of automating sales. His device was crude, but effective. A person inserted coins and pulled a lever that opened a compartment from which a copy of The Age of Reason could be retrieved without human intervention. Police had no one to arrest for selling seditious material.

The book vending machine didn’t keep Carlisle out of jail — he would spend nine years locked up for acts of political rebellion. Nor was he able to patent his device. I admire the hell out of him, tho.

Jump ahead to the early twentieth century and vending machines were being used in France and Germany to sell newspapers, postcards, maps, as well as books. The idea crossed the English Channel in 1937. Allen Lane, who single-handedly invented the modern paperback and founded Penguin Books with his brothers in 1935, launched the Penguincubator two years later. Based on the German machines, it was described by the Times as “an unfamiliar contraption of metal and glass”. Lane installed it at 66 Charing Cross Road, outside Collet’s bookshop.

Lane’s contraption was no more successful than Carlile’s. It got wheeled out of Collet’s shop at closing time every night and wheeled back in every morning when the shop opened. Another Charing Cross bookseller recalled seeing letters shoved under the shop’s door each morning complaining of coins lost in the machine. Customers also learned that you only had to pound the side of the box in order for it to disgorge about a third of its inventory. The Bookseller reported that when this was pointed out to the manager of Collet’s, he “gave his incontinent robot a terrific thrashing. As a result of this all the rest of the Penguin’s promptly fell out.”

That perhaps explains why I couldn’t find a mention of the Penguincubator in Stuart Kells’ otherwise excellent book, Penguin and the Lane Brothers: The Untold Story of a Publishing Revolution.

Ken Whyte, “Have I got a business for you!”, SHuSH, 2024-09-06.