HardThrasher

Published 17 Apr 2025The speed with which a theory had to be put into practice, and the opening phase of the raid itself.

(more…)

April 19, 2025

Dambusters – Part 2 – The Countdown to the Raid

April 7, 2025

Dambusters Part 1 – The Battle of the Ruhr

HardThrasher

Published 5 Apr 2025The background to the Dams raid; how it came into being and how it fitted into the assault on Nazi Germany. In which we discuss Banes Wallis, Arthur Harris and a man called Winterbotham.

THESE LINKS ARE ONLY FOR THE SERIOUSLY SEXY

Merch! – https://hardthrasher-shop.fourthwall.com

Patreon – https://www.patreon.com/LordHardThrasherBibliography

James Holland – Dambusters: the Races to Smash the Dams 1943

Max Hastings – Chastise – The Dambusters Story

Alan Cooper – The Battle of the Ruhr

Adam Tooze – The Wages of Destruction

Martin Millbrook and Chris Everett – The Bomber Command War Diaries

Edward Westerman – Flak German Anti Aircraft Defences [sic] 1914-1945

Tami Davis Biddle – Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare

Donald A Miller – Masters of the Air

March 30, 2025

QotD: FDR, Mackenzie King and Churchill in 1940

On May 30th 1940, just after the war cabinet crisis & during the Dunkirk evacuation;

Winston Churchill was informed by the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, of more dreadful news.

Roosevelt had no faith in Churchill nor Britain, and wanted Canada to give up on her.

Roosevelt thought that Britain would likely collapse, and Churchill could not be trusted to maintain her struggle.

Rather than appealing to Churchill’s pleas of aid — which were politically impossible then anyway — Roosevelt sought more drastic measures.

A delegation was summoned [from] Canada.

They requested Canada to pester Britain to have the Royal Navy sent across the Atlantic, before Britain’s seemingly-inevitable collapse.

Moreover, they wanted Canada to encourage the other British Dominions to get on board such a plan.

Mackenzie King was mortified. Writing in his diary,

“The United States was seeking to save itself at the expense of Britain. That it was an appeal to the selfishness of the Dominions at the expense of the British Isles. […] I instinctively revolted against such a thought. My reaction was that I would rather die than do aught to save ourselves or any part of this continent at the expense of Britain.”

On the 5th June 1940, Churchill wrote back to Mackenzie King,

“We must be careful not to let the Americans view too complacently prospect of a British collapse, out of which they would get the British Fleet and the guardianship of the British Empire, minus Great Britain. […]

Although President [Roosevelt] is our best friend, no practical help has been forthcoming from the United States as yet.”

Another example of the hell Churchill had to endure — which would have broken every lesser man.

Whilst the United States heroically came to aid Britain and her Empire, the initial relationship between the two great powers was different to what is commonly believed.

(The first key mover that swung Roosevelt into entrusting Churchill to continue the struggle — and as such aid would not be wasted on Britain — was when Churchill ordered the Royal Navy’s Force H to open fire and destroy the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kébir — after Admiral Gensoul had refused the very reasonable offers from Britain, despite Germany and Italy demanding the transference of the French Fleet as part of the armistices.)

Andreas Koreas, Twitter, 2024-12-27.

March 29, 2025

The Life of Plutarch

MoAn Inc.

Published 19 Sept 2024#AncientHistory #AncientGreece #Plutarch

Donate Here: https://www.ko-fi.com/moaninc

March 23, 2025

QotD: Herbert Hoover as president

Herbert Hoover spent his entire presidency miserable.

First, he has no doubt that the economy is going to crash. It’s been too good for too long. He frantically tries to cool down the market, begs moneylenders to stop lending and bankers to stop banking. It doesn’t work, and the Federal Reserve is less concerned than he is. So he sits back and waits glumly for the other shoe to drop.

Second, he hates politics. Somehow he had thought that if he was the President, he would be above politics and everyone would have to listen to him. The exact opposite proves true. His special session of Congress comes up with the worst, most politically venal tariff bill imaginable. Each representative declares there should be low tariffs on everything except the products produced in his own district, then compromises by agreeing to high tariffs on everything with good lobbyists. The Senate declares that the House of Representatives is corrupt nincompoops and sends the bill back in disgust. Hoover has no idea how to solve this problem except to ask the House to do some kind of rational economically-correct calculation about optimal tariffs, which the House finds hilarious. “Opposed to the House bill and divided against itself, the Senate ran out the remaining seven weeks [of the special session] in a debauch of taunts, accusations, recriminations, and procedural argument.” The public blames Hoover, pretty fairly – a more experienced president would have known how to shepherd his party to a palatable compromise.

Also, there are crime waves, prison riots, bootlegging, and a heat wave during which Washington DC is basically uninhabitable. Also, at one point the White House is literally on fire.

… and then the market finally crashes. Hoover is among the first to call it a Depression instead of a Panic – he thinks the new term might make people panic less. But in fact, people aren’t panicking. They assume Hoover has everything in hand.

At first he does. He gathers the heads of Ford, Du Pont, Standard Oil, General Electric, General Motors, and Sears Roebuck and pressures them to say publicly they won’t fire people. He gathers the AFL and all the union heads and pressures them to say publicly they won’t strike. He enacts sweeping tax cuts, and the Fed enacts sweeping rate cuts. Everyone is bedazzled […] Six months later, employment is back to its usual levels, the stock market is approaching its 1929 level, and Democrats are fuming because they expect Hoover’s popularity to make him unbeatable in the midterms. I got confused at this point in the book – did I accidentally get a biography from an alternate timeline with a shorter, milder Great Depression? No – this would be the pattern throughout the administration. Hoover would take some brilliant and decisive action. Economists would praise him. The economy would start to look better. Everyone would declare the problem solved – especially Hoover, sensitive both to his own reputation and to the importance of keeping economic optimism high. Then the recovery would stall, or reverse, or something else would go wrong.

People are still debating what made the Great Depression so long and hard. Whyte’s theory, insofar as he has one at all, is “one thing after another”. Every time the economy started to go up (thanks to Hoover), there was another shock. Most of them involved Europe – Germany threatening to default on its debts, Britain going off the gold standard. A few involved the US – the Federal Reserve made some really bad calls. The one thing Whyte is really sure about is that his idol Herbert Hoover was totally blameless.

He argues that Hoover’s bank relief plan could have stopped the Depression in its tracks – but that Congressional Democrats intent on sabotaging Hoover forced the plan to publicize the names of the banks applying. The Democrats hoped to catch Hoover propping up his plutocrat friends – but the change actually had the effect of making banks scared to apply for funding and panicking the customers of banks that were known to have applied. He argues that the “Hoover Holiday” – a plan to grant debt relief to Germany, taking some pressure off the clusterf**k that was Europe – was a masterstroke, but that France sabotaged it in the interests of bleeding a few more pennies from its arch-rival. International trade might have sparked a recovery – except that Congress finally passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, the end result of the corruption-plagued tariff negotiations, just in time to choke it off.

Whyte saves his barbs for the real villain: FDR. If the book is to be believed, Hoover actually had things pretty much under control by 1932. Employment was rising, the stock market was heading back up. FDR and his fellow Democrats worked to tear everything back down so he could win the election and take complete credit for the recovery. The wrecking campaign entered high gear after FDR won in 1932; he was terrified that the economy might get better before he took office, and used his President-Elect status to hint that he was going to do all sorts of awful things. The economy got skittish again and obediently declined, allowing him to get inaugurated at the precise lowest point and gain the credit for recovery he so ardently desired.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

March 3, 2025

All The Basics About XENOPHON

MoAn Inc.

Published 7 Nov 2024I actually found this video really tricky considering I want to go into the texts of Xenophon and if I told you everything about the march of the ten thousand then I would have just told you the whole Anabasis?? Which defeats the whole purpose of an introductory video?? So I PROMISE more clarity will come in future videos as Xenophon himself breaks down his journey home from Persia and why they were there in the first place. Therefore, you have ALL OF THAT to look forward to — coming soon!!!

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Henry VIII, Lady Killer – History Hijinks

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 3 Feb 2023brb I’m blaring “Haus of Holbein” from Six the Musical on the loudest speakers I own.

SOURCES & Further Reading:

Britannica “Henry VIII” (https://www.britannica.com/biography/…, History “Who Were The Six Wives of Henry VIII” (https://www.history.com/news/henry-vi…), The Great Courses lectures: “Young King Hal – 1509-27”, “The King’s Great Matter – 1527-30”, “The Break From Rome – 1529-36”, “A Tudor Revolution – 1536-47”, and “The Last Years of Henry VIII – 1540-47” from A History of England from the Tudors to the Stuarts by Robert Bucholz

(more…)

February 8, 2025

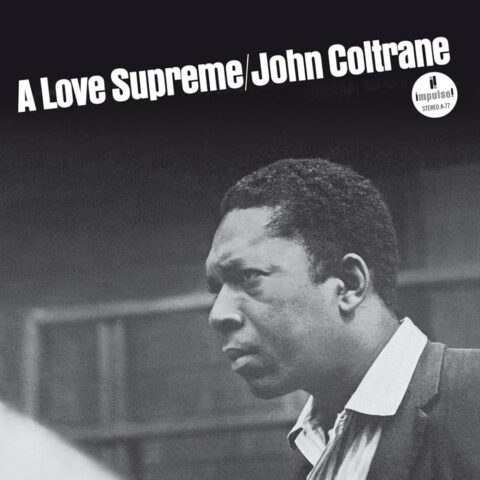

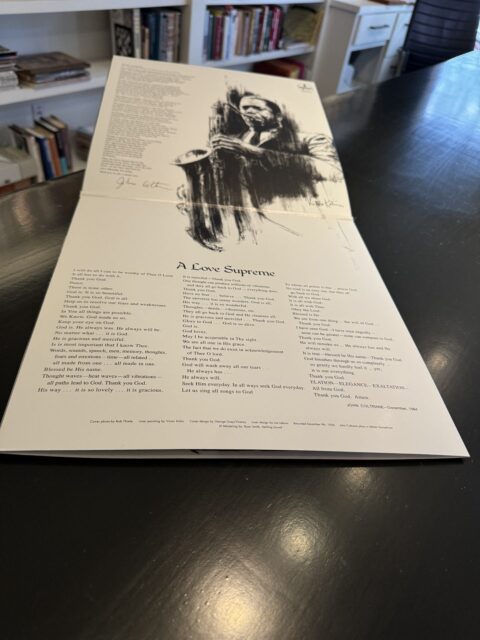

A Love Supreme after 60 years

John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme was one of the first four jazz albums I ever bought. It quickly became my favourite and led me to listening to a lot more of Coltrane’s work. Some I loved nearly as much (Giant Steps, Blue Train, The Complete Africa/Brass Sessions) while others I just bounced off (Sun Ship, Interstellar Space, Stellar Regions), but most became fixtures of my various jazz playlists.

Ted Gioia notes the moment as A Love Supreme hits 60 years after release:

Ivy League theoretical physicist Stephon Alexander will even tell you that John Coltrane has a lot in common with Albert Einstein. People still consult the saxophonist’s mathematical analysis — the so-called Coltrane Circle — as if it were a source of esoteric wisdom.

But in 1964, John Coltrane was also a father. John Coltrane Jr. was born on August 26, 1964 — the first of his three children. Ravi Coltrane arrived in 1965, and Oran in 1967.

You wouldn’t think that Coltrane could find time for anything else at the close of the Summer of 1964. But he did.

At that juncture, he disappeared into an upstairs guest room at his home. And spent day after day with just a pen, some paper, and his horn.

He emerged five days later. “It was like Moses coming down from the mountain,” Alice later recalled. “It was so beautiful. He walked down and there was that joy, that peace in his face, tranquility.”

“This is the first time that I have received all of the music for what I want to record,” he told her.

Note that word: Received. He didn’t say composed. He didn’t say created. It was a gift from something larger than himself.

This was the music John Coltrane would perform in the studio three months later. It’s know today as A Love Supreme.

Coltrane said that his music was his gift back to the Divine.

He made that clear in his liner notes, which opened with an invocation in capital letters: DEAR LISTENER: ALL PRAISE BE TO GOD TO WHOM ALL PRAISE IS DUE…

But if there were still any doubt, Coltrane also included a devotional poem — which began:

I will do all I can to be worthy of Thee O Lord.

It all has to do with it.

Thank you God.

Peace …Needless to say, this was not typical for jazz liner notes in the mid-1960s. Or at any time, for that matter.

And it almost certainly would limit sales — or so the conventional wisdom went back then. A few months later, Capitol Records execs had a meltdown when Brian Wilson wanted to give the name “God Only Knows” to a song. But that was nothing compared to the full-blown ritual that Coltrane was now unleashing on the hip jazz audience.

I use the word ritual advisedly here. I’ve heard other people describe A Love Supreme as a suite, but they’re missing the whole point. I have no doubt that Coltrane intended this ritualistic effect.

He even starts chanting toward the end of the opening track.

This was first time Coltrane’s voice had ever been featured on a studio recording. And he didn’t sing a love song or belt out a blues. Instead he was chanting:

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme

A love supreme …He chants that phrase nineteen times in a row.

January 28, 2025

QotD: Was Einstein a science-denier?

Albert Einstein was a charmingly blunt man. For instance, in 1952 he wrote a letter to his friend and fellow physicist Max Born where he admits that even if the astronomical data had gone against general relativity, he would still believe in the theory:

Even if there were absolutely no light deflection, no perihelion motion and no redshift, the gravitational equations would still be convincing because they avoid the inertial system … It is really quite strange that humans are usually deaf towards the strongest arguments, while they are constantly inclined to overestimate the accuracy of measurement.

In a few short sentences Einstein completely repudiates the empiricist spirit which has ostensibly guided scientific inquiry since Francis Bacon. He doesn’t care what the data says. If the experiment hadn’t been run, he would still believe the theory. Moreover, should the data have disconfirmed his theory, who cares? Data are often wrong.

This is not, to put it mildly, the official story of how science gets made. In the version most of us were taught, the process starts with somebody noticing patterns or regularities in experimental data. Scientists then hypothesize laws, principles, and causal mechanisms that abstract and explain the observed patterns. Finally, these hypotheses are put to the test by new experiments and discarded if they contradict their results. Simple, straightforward, and respectful of official pieties. The Schoolhouse Rock of science. Or as Einstein once described it:

The simplest idea about the development of science is that it follows the inductive method. Individual facts are chosen and grouped in such a way that the law, which connects them, becomes evident. By grouping these laws more general ones can be derived until a more or less homogeneous system would have been created for this set of individual facts.

See? It’s as easy as that. But then, Einstein finishes that thought with: “[t]he truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a manner almost diametrically opposed to induction”.

Was Einstein a science-denier? I’m obviously kidding, but this is still pretty jarring stuff to read. How did he get this way? Einstein’s Unification is the story of the evolution of Einstein’s philosophical views, disguised as a story about his discovery of general relativity and his quixotic attempts at a unified field theory. It’s a gripping tale about how Einstein tried to do science “correctly”, experienced years of frustration, almost had priority for his discoveries snatched away from him, then committed some Bad Rationalist Sins at which point things immediately began to work. This experience changed him profoundly, and maybe it should change us too.

John Psmith, “REVIEW: Einstein’s Unification, by Jeroen van Dongen”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2024-05-27.

January 27, 2025

The Rise of Augustus – The Conquered And The Proud 12

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 4 Sept 2024Continiung the series “The Conquered and the proud”, we come to the early days of the young Octavian, the man who would become Caesar Augustus and found the Principate, the rule of emperors — a system that would last for centuries and see the Roman empire reach the pinnacle of its prosperity and population.

Just eighteen years old when Julius Caesar was murdered, his great nephew was named as principal heir in his will. This mean that he took his name and the bulk of his property. However, this ambitious teenager took it to mean that he should also succeed to Caesar’s power. Incredibly, after fourteen years of bloody struggle, he did just that.

January 16, 2025

Augustus and the Roman Army – the first emperor and the creation of the professional army

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 7 Aug 2024We take a look at Caesar Augustus, the first emperor (or princeps) of Rome and the great nephew of Julius Caesar. Ancient sources — and Shakespeare and Hollywood — depict him as politician and no soldier in contrast to Mark Antony. How true is this? More importantly, how did the man who created the imperial system and re-shaped society change the Roman army?

This video is based on a talk I gave in 2014 at the Roman Legionary Museum in Caerleon — a museum and adjacent sites, well worth a visit for anyone in or near South Wales.

January 13, 2025

The Writings of Cicero – Cicero and the Power of the Spoken Word

seangabb

Published 25 Aug 2024This lecture is taken from a course I delivered in July 2024 on the Life and Writings of Cicero. It covers these topics:

• Introduction – 00:00:00

• The Deficiencies of Modern Oratory – 00:01:20

• The Greeks and Oratory – 00:06:38

• Athens: Government by Lottery and Referendum – 00:08:10

• The Power of the Greek Language – 00:17:41

• The General Illiteracy of the Ancients – 00:21:06

• Greek Oratory: Lysias, Gorgias, Demosthenes – 00:28:38

• Macaulay as Speaker – 00:34:44

• Attic and Asianic Oratory – 00:36:56

• The Greek Conquest of Rome – 00:39:26

• Roman Oratory – 00:43:23

• Cicero: Early Life – 00:43:23

• Cicero in Greece – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Early Legal Career – 00:46:03

• Cicero: Defence of Roscius – 00:47:49

• Cicero as Orator (Sean Reads Latin) – 00:54:45

• Government of the Roman Empire – 01:01:16

• The Government of Sicily – 01:03:58

• Verres in Sicily – 01:06:54

• The Prosecution of Verres – 01:11:20

• Reading List – 01:24:28

(more…)

January 12, 2025

QotD: Kaiser Wilhelm II

Following the all-too brief reign of Frederick III, his son Wilhelm II, grandson of the first German Emperor, took power in 1888 (known as the “year of the three emperors”). From the start, the young Wilhelm was determined not to be the reserved figure of his grandfather and still less the liberal reformer that his ill-fated father had wished to be. Instead, Wilhelm believed it was his right and duty to be directly involved in the country’s governing.

This was completely incompatible with Bismarck’s system, which had centralized power upon his own person. With uncharacteristic focus and subtlety, Wilhelm sought to reclaim the power that his grandfather had ceded to the chancellor. This was not to prove especially difficult; Bismarck’s position had always relied upon his indispensability to the emperor. Thus, when Bismarck offered his resignation (as he often did during disputes) Wilhelm merely accepted it. The last great man of the wars of unification had now disappeared from the balance.

While the German Empire never became a true autocracy, Wilhelm succeeded in creating what historian, and biographer of the Kaiser, John C. Röhl called a “personalist” system.1 The Kaiser had significant power over personnel. Promotions in the officer corps required his assent. Advancement within civil service (from which civilian ministers were appointed) was also dependent on his favor. By exercising this power, Wilhelm was able to ensure the highest levels of the German government were men agreeable to his point of view. Though they were not mere “yes men”, Wilhelm ensured that they were knowingly dependent on his favor for their position. The Kaiser — even to the end of the monarchy — exercised considerable “negative power” (as Röhl termed it.)2 While Wilhelm’s ability to actively make policy was limited, anything he disapproved of was simply not proposed.

Wilhelm II’s reign marked a departure from the more restrained leadership of his predecessors, as he sought to assert direct influence over the German Empire’s governance and military affairs. This shift toward a more “personalist” system, where loyalty to the Kaiser outweighed true statesmanship, weakened the effectiveness of German leadership and contributed to its eventual strategic missteps. The rigid adherence to the Schlieffen Plan and the technocratic focus on material advantages, such as firepower and mobility, overshadowed the need for adaptable strategic thinking. These failures in both leadership and military planning set the stage for Germany’s disastrous involvement in World War I, where an empire led by personalities rather than policies was ill-prepared for the complexities of modern warfare. Ultimately, Wilhelm’s influence and the culture of sycophancy he fostered played a pivotal role in leading Germany down the path of ruin.

Kiran Pfitzner and Secretary of Defense Rock, “The Kaiser and His Men: Civil-Military Relations in Wilhelmine Germany”, Dead Carl and You, 2024-10-02.

1. John C. G. Röhl, Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Concise Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2014).

2. Negative power refers to the ability of an actor or group to block, veto, or prevent actions, decisions, or policies from being implemented, rather than directly initiating or shaping outcomes.

January 7, 2025

Caesar’s dictatorship and the Ides of March – The Conquered And The Proud 11

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published 31 Jul 2024Continuing “The conquered and the proud”, this time we look at Julius Caesar as dictator in Rome, about his activities and reforms and his murder on the 15th March — The Ides of March — in 44 BC. We talk about Brutus, Cassius and the other conspirators and what motivated them.

December 29, 2024

QotD: Churchill as author and Prime Minister

“Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy, an amusement; then it becomes a mistress, and then a master, and then a tyrant.” Those owning a business plan, devising an advertising proposal, plotting a military stratagem, drafting an architectural blueprint, painting a picture, crafting sculpture or ceramics, penning a volume, sermon or speech — or editing The Critic — will, I suspect, be nodding in recognition of this.

The words were those of Winston Churchill, the 150th anniversary of whose birthday, 30 November 1874, falls this year. In addition to submitting canvases to the Royal Academy of Arts under the pseudonym David Winter — which resulted in his election as Honorary Academician in 1948 — and twice being Prime Minister for a total of eight years and 240 days, he has merited far more biographies than all his predecessors and successors put together. This summer I completed one more volume to add to the vast collection. My purpose here is less to blow my own trumpet than to ponder why Churchill remains so popular as a subject and survey what is new in print for this anniversary year.

It is tempting to see his career through many different lenses, for his achievements during a ninety-year lifespan spanning six monarchs encompassed so much more than politics, including that of painter. The only British premier to take part in a cavalry charge under fire, at Omdurman on 2 September 1898, he was also the first to possess an atomic weapon, when a test device was detonated in Western Australia on 3 October 1952. Besides being known as an animal breeder, aristocrat, aviator, big-game hunter, bon viveur, bricklayer, broadcaster, connoisseur of cigars and fine fines (his preferred Martini recipe included Plymouth gin and ice, “supplemented with a nod toward France”), essayist, gambler, global traveller, horseman, journalist, landscape gardener, lepidopterist, monarchist, newspaper editor, Nobel Prize-winner, novelist, orchid-collector, parliamentarian, polo player, prison escapee, public schools fencing champion, rose-grower, sailor, soldier, speechmaker, statesman, war correspondent, war hero, warlord and wit, one of his many lives was that of writer-historian.

Most of his long life revolved around words and his use of them. Hansard recorded 29,232 contributions made by Churchill in the Commons; he penned one novel, thirty non-fiction books, and published twenty-seven volumes of speeches in his lifetime, in addition to thousands of newspaper despatches, book chapters and magazine articles. Historically, much understanding of his time is framed around the words he wrote about himself. “Not only did Mr. Churchill both get his war and run it: he also got in the first account of it” was the verdict of one writer, which might be the wish of many successive public figures. Acknowledging his rhetorical powers, which set him apart from all other twentieth century politicians, his patronymic has gravitated into the English language: Churchillian resonates far beyond adherence to a set of policies, which is the narrow lot of most adjectival political surnames.

“I have frequently been forced to eat my words. I have always found them a most nourishing diet”, Churchill once quipped at a dinner party, and on another occasion, “history will be kind to me for I intend to write it”. Yet “Winston” and “Churchill” are the words of a conjuror, that immediately convey a romance, a spell, and wonder that one man could have achieved so much. It is an enduring magic, and difficult to penetrate. In 2002, by way of example, he was ranked first in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons of All Time — amongst many similar accolades. A less well-known survey of modern politics and history academics conducted by MORI and the University of Leeds in November 2004 placed Attlee above Churchill as the 20th Century’s most successful prime minister in legislative terms — but he was still in second place of the twenty-one PMs from Salisbury to Blair.

Peter Caddick-Adams, “Reading Winston Churchill”, The Critic, 2024-09-22.