If you were to pick one company that symbolizes how America has changed and been changed over the last half century or so, it would be General Electric. The company founded by Thomas Edison is in many ways a microcosm of the American economy over the last century or more. It rose to become an industrial giant in the 20th century, the symbol of America manufacturing prowess. It then transformed into a giant of the new economy in the 1990’s, a symbol of the new America.

Today, General Electric is a company in decline. After a series of problems following the financial crisis of 2008, the company has steadily sold off assets and divisions in an effort to fix its financial problems. In 2019, Harry Markopolos, the guy who sniffed out Bernie Madoff, accused them of $38 billion in accounting fraud. The stock has been removed from the Dow Jones Industrial composite. […] General Electric transformed from a company that made things into a financial services company that owned divisions that made things. Like the American economy in the late 20th century, the company shifted its focus from making and creating things to the complex game of financializing those processes.

Like many companies in the late 20th century, General Electric found that their potential clients were not always able to come up with the cash to buy their products, so they came up with a way to finance those purchases. This is an age-old concept that has been with us since the dawn of time. Store credit is a way for the seller to profit from the cash poor in the market. He can both raise his price and also collect interest on the payments made by his customers relying on terms.

For American business, this simple idea turned into a highly complex process, involving tax avoidance strategies and the capitalization of the products and services formerly treated as business expenses. Commercial customers were no longer buying products and services, but instead leasing them in bundled services packages, financed at super-low interest rates and tax deductible. Whole areas of the supply chain shifted from traditional purchases to leased services.

[…]

That is the real lesson of General Electric. The company became something like the old Mafia bust-outs. The whole point of the business was to squeeze every drop of value from clients and divisions. Instead of running up the credit lines and burning down the building for the insurance, General Electric turned the human capital of companies into lease and interest payments. They were not investing and creating, they were monetizing and consuming whatever it touched. […] The cost of unwinding the company back into a normal company will be high, maybe too high for them to survive. The same can be said of the American economy. It will have to be unwound, but there will be no bailout. Instead, it will have to unwind quickly and painfully, in order to become a normal economy again. [NR: According to Wiki, “GE Aerospace, the aerospace company, is GE’s legal successor. GE HealthCare, the health technology company, was spun off from GE in 2023. GE Vernova, the energy company, was founded when GE finalized the split. Following these transactions, GE Aerospace took the General Electric name and ticker symbols, while the old General Electric ceased to exist as a conglomerate.“]

The Z Man, “GE: The Story Of America”, The Z Blog, 2020-06-29.

January 24, 2026

QotD: General Electric

January 18, 2026

Mark Carney’s actual jobs before becoming Prime Minister

On the social media site formerly known as Twitter, Ezra Levant explains the various jobs Mark Carney has held compared to what many Canadians think he’s done:

Laura Stone @l_stone

Unifor President Lana Payne calls China EV deal “a self-inflicted wound to an already injured Canadian auto industry”. Says providing a foothold to cheap Chinese EVs “puts Canadian auto jobs at risk while rewarding, labour violations and unfair trade practices”. #onpoliI think there’s a misconception amongst Canada’s chattering classes that Mark Carney is an experienced and successful businessman and executive.

He wasn’t. He wasn’t CEO of Brookfield. He was its chairman, overseeing quarterly board meetings and spending the rest of his time flying around to different globalist conferences at the UN or WEF.

He was more of a mascot, a symbol, an ambassador of Brookfield. He didn’t negotiate deals or turn around companies. He did photo-ops.

Before that, he worked at the Bank of England, and before that, the Bank of Canada.

No Googling: can you name a single actual duty of that job? Can you tell me what Carney actually achieved?

He wafted up from fake job to fake job — like Justin Trudeau did, but instead of being a surf instructor and a substitute teacher, he had meaningless executive jobs.

And now when it’s time to shine … he doesn’t know what to do.

It’s been a year, and he has no deal with Trump, despite saying that was his chief focus.

What exactly did he achieve in Beijing? The tariffs against Saskatchewan were lifted — so that merely brings us back to the status quo ten months ago. Nothing else. No investments in Canada, which was the pretext of the trip. Just a capitulations, to allow the dumping of 49,000 Chinese EV cars, with their spyware and malware.

But he looks good in a suit and says ponderous words like “catalyze” and “transformative”. And that’s enough to impress the Parliamentary Press Gallery. Not that they needed much impressing — they’re all on his payroll already, through his massive journalism subsidies. They’re too busy holding the opposition to account to take notice of this latest disaster.

But the regime media shouldn’t feel too bad about being conned. Carney tricked Doug Ford pretty good, didn’t he?

December 15, 2025

The wrong way to address the credit card debt issue

Daniel Mitchell says that US politicians seem to have identified a real problem and they’re proposing solutions. Unfortunately, the biggest proposal not only won’t solve the problem … it’ll make it worse for the most vulnerable credit card debtors:

“Credit Cards” by Sean MacEntee is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

According to a new report from the New York Federal Reserve, Americans have accumulated over one trillion in credit card debt, an all-time high. It’s a record that would make financial advisor Dave Ramsey lose the remaining hair on his head, but even worse, the share of balances in serious delinquency climbed to a nearly financial-crash level of 7.1%. In other words, Americans are borrowing more and paying back less.

This alarming trend has naturally drawn the attention of politicians eager to offer a quick fix.

Unfortunately, the solution gaining bipartisan traction is a blanket cap on credit card interest rates. Like most political quick fixes, it is an economic prescription guaranteed to harm the very individuals it claims to protect.

The impulse to cap rates is rooted in a fundamental economic misunderstanding. It treats the interest rate as an arbitrary fee levied by greedy banks rather than the essential economic mechanism it is: the price of risk. This misguided philosophy is embodied in the legislation introduced by the populist duo of Senators Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT), which seeks to impose a nationwide cap on Annual Percentage Rates (APRs), sometimes as low as 10%.

Make no mistake: two politicians don’t know better than the marketplace and the law of supply and demand that governs it. The consequences of imposing a price ceiling on credit are not debatable. They are historically certain. Interest rates on credit cards are higher than on mortgages, for instance, because credit cards are unsecured debt. If a borrower defaults, the bank cannot seize collateral to cover the loss. The interest rate must therefore be high enough to reflect the expected default rate across the entire high-risk pool.

It’s wrongheaded. Faced with the possibility of a government-imposed price cap, credit card companies would of course respond as any company would. They will stop extending credit to those who will possibly not pay them back. Studies show that even a cap as high as 18% would put nearly 80% of subprime borrowers at risk of losing access to credit. In other words, the 10% cap proposed by the Hawley–Sanders alliance would have truly devastating effects for credit access, potentially eliminating millions of accounts.

The victims of this policy will not be the wealthy, who already qualify for prime rates; nor will they be the financially literate, who pay their balances in full. The victims will be the economically vulnerable, the working-class single mother needing a short-term buffer, the recent immigrant attempting to build a credit score, or the young person trying to establish his or her financial footing. For these individuals, the Hawley–Sanders policy will deliver not cheap credit, but no credit at all.

November 11, 2025

How not to solve your housing affordability crisis

On the social media site formerly known as Twitter, Devon Eriksen explains why allowing fifty-year mortgages are not the solution that financial journalists seem to think they are:

Wendy O @CryptoWendyO

I don’t think a 50 year mortgage is bad.

It gives everyone more flexibility financially

You can pay a mortgage off early

Not sure how else to lower home costs in 2025Buyers: “How much will this house cost me?”

Sellers: “What’s your budget?”

Buyers: “Well, it was 500K, but with these new fifty year mortgages, I think it could stretch to million.”

Sellers: “I have an astonishing coincidence to report.”

Look, I don’t know exactly who’s retarded enough to need to hear this, but if you throw money at something, you get more of it.

Which means that if you subsidize demand, you get more demand.

And if you have the same supply, and more demand, price goes up.

This is how the federal Stafford Loan program made college a gateway to permanent debt slavery. Subsidize demand, price goes up.

The reason people don’t understand this is that most people are only smart enough to think about individuals, not populations.

They think if you have more money, you can buy more things, as if things come from the item store in a Japanese console RPG, where the store always has infinity stuff to sell you, and infinity money to buy your loot.

People who are capable of thinking about large groups quickly realize that money is just a way of distributing things.

Like, there’s a limited supply of things, and you’re just choosing who gets them. Having more money doesn’t make more things.

Except … it should, shouldn’t it?

Eventually?

Like, if apples get super expensive, because somebody invented a new kind of apple that’s so delicious that everyone wants them, then the price of those apples goes up, so more people start growing them.

So why doesn’t that work with houses and colleges?

Why don’t the super-inflated prices of those things inspire profit-minded people to make more?

It’s almost as if there were some sort of gatekeeper, whose permission you needed to make a house or a university.

But that’s impossible, because this is a totally capitalist country, so you can just do things, right?

Ian Runkle/Runkle of the Bailey chimes in:

Okay, let’s talk about 50 year mortgages.

First, let’s talk about what sets the price in a market where there’s more demand than supply. It’s set by what people can afford to pay, which means the payment/month.

What that means in practical terms is that the total price isn’t the limiter. It’s the monthly payment.

So, if X house is going for a price that has a 2500/month payment, the market is going to land total prices on a 2500/month payment.

So, increasing the mortgage terms makes things more affordable for about six months before the market adjusts. After that, it stops making it more affordable.

But “affordable” here doesn’t mean inexpensive. In fact, quite the opposite. Extending from a 30 year to a 50 year mortgage is likely to double the cost of credit.

But that’s before the prices adjust upward to “eat” the supposed affordability gains.

This doesn’t make houses more affordable, it makes them more expensive by far.

October 3, 2025

Women and credit card access … another “just so” story

Janice Fiamengo debunks a common “just so” story about women only gaining the right to hold a credit card in the 1970s:

A few years ago, I started hearing that women, before feminism, couldn’t have their own credit cards. Or they couldn’t get one without a man’s signature. Or married women couldn’t have one in their own name. Divorced women, apparently, couldn’t get credit at all. Men conspired to keep women powerless and dependent.

THANK THE GODDESS FOR FEMINISM!

Just last June, on the podcast Diary of a CEO (in an episode viewed by nearly two million people), three feminists debating feminism agreed that, in the words of one of the panelists, “None of us could get a credit card a few decades ago … We couldn’t have anything …” (see 1:50:37).

Before correcting herself, in fact, the panelist had started to say, “None of us could get a credit card a couple of decades ago …”

The statement struck me with the full force of the ludicrous. I started school in 1970. My teachers were nearly all women, at least half of them unmarried. They certainly seemed to live full, normal lives in obeisance to no man. They were paid a salary; they had bank accounts; they owned cars; they bought things and went on vacations.

My mother had worked in an insurance office for years both before and after she married my father in 1956. She had purchased appliances and paid her own rent, helped my father buy his first commercial fishing boat, and handled all the household expenses when my dad was away fishing for months every summer.

My friends’ mothers were similarly active and self-determining. Were all these women actually hobbled by the patriarchy, cut off from the economy?

Received knowledge would have us believe so. Last year, The Globe and Mail published a paid advertisement for Women’s History Month titled “50 Years Ago: Women Got the Right to Have Credit Cards”. Written by a financial services company seeking to drum up business, the article repeated the popular story that women in North America could not get their own credit cards until 1974.

Credit cards were one of the growth areas for banks and other financial service companies in the 1960s and 70s … from something only relatively wealthy travellers and business executives used, they expanded to become widely used by ordinary consumers for all kinds of purchases. Consumers benefitted from access to useful financial tools, while banks enjoyed the profits from the widespread use of credit cards. So where did the idea that they were male-only come from?

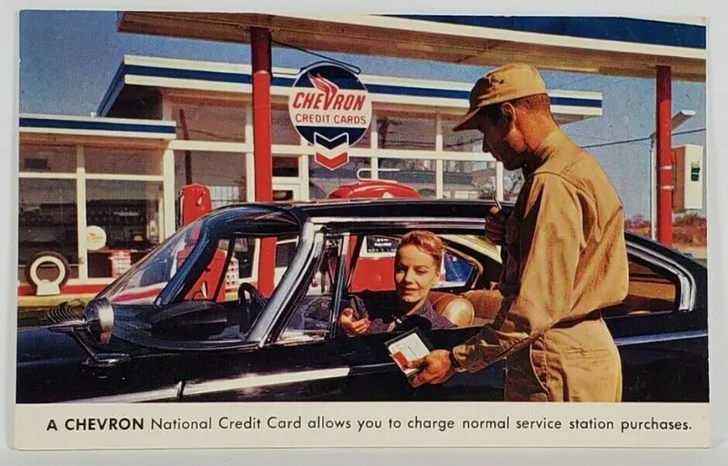

The reality is that from the 1950s on, credit cards were a new invention being aggressively marketed to both men and women. Advertising from the era shows how keen credit card companies were to target female customers, how eager to tap into women’s spending power.

Originally introduced as a convenience for travelers on business, credit cards began to expand their purview in the late 1950s. Bank Americard (later Visa) became the first consumer credit card in 1958. A network of banks formed the Interbank Card Association, originally named Master Charge (later Mastercard), in 1966.

Yet we are somehow to believe that half the population was deliberately excluded from this new consumer venture for no other reason than that they were female?

“It wasn’t until 1974 that women were allowed to open a credit card under their own name,” the Globe article states emphatically. “Before 1974, if women wanted to open a credit card, they would be asked a bunch of intrusive questions, like if they were married or whether they planned to have children. If a woman was married, she could (hopefully) get a credit card with her husband. But single, divorced, or widowed women weren’t allowed to get a credit card of their own — they had to have a man cosign for the credit application.”

The explanation is dramatic and incoherent, undoing its own logic from the beginning. It backtracks to allege that women were in fact “allowed” to have a credit card so long as they answered “a bunch of intrusive questions” or found a co-signer. Even this lesser claim is false, but it is rather different from the prior assertion about women “not having the right” to a card.

At a time when many married women either did not work outside the home or worked only part-time and on a temporary basis, there would have been nothing unreasonable about a woman’s husband co-signing her credit card application. Many married women were happy to purchase what they wanted on the assurance that their husbands would pay the bill when it came in, and credit card issuers saw joint accounts as a way of ensuring payment.

Update, 4 October: Welcome, Instapundit readers! Please have a look around at some of my other posts you may find of interest. I send out a daily summary of posts here through my Substack – https://substack.com/@nicholasrusson that you can subscribe to if you’d like to be informed of new posts in the future.

May 29, 2025

QotD: FDR and Herbert Hoover in the Great Depression

November 1932. Hoover has just lost the election, but is a lame duck until March. The European debt crisis flashes up again. Hoover knows how to solve it. But:

He had already met with congressional leaders and learned, as he had suspected, that they would not change their stance without Roosevelt’s support. Seized with the urgency of the moment, he continued to bombard his opponents with proposals for cooperation toward solutions, going so far as to suggest that Democratic nominees, not Republicans, be sent to Europe to engage in negotiations, all to no avail. Notwithstanding what editorialists called his “personal and moral responsibility” to engage with the outgoing administration, Roosevelt had instructed Democratic leaders in Congress not to let Hoover “tinker” with the debts. He had also let it be known that any solution to the problem would occur on his watch – “Roosevelt holds he and not Hoover will fix debt policy”, read the headlines. Thus ended what the New York Times called Hoover’s magnanimous proposal for “unity and constructive action”, not to mention his 12-year effort to convince America of its obligation and self-interest in fostering European political and financial stability …

During the debt discussions and to some extent as a result of them, the economy turned south again. Several other factors contributed. Investors were exchanging US dollars for gold as doubt spread about Roosevelt’s intentions to remain on the gold standard. Gold stocks in the Federal Reserve thus declined, threatening the stability of the financial sector … what’s more, the effectiveness of [Hoover’s bank support plan], which had succeeded in stabilizing the banking system, was severely compromised by [Democrats’] insistence on publicizing its loans, as the administration had warned. For these reasons, Hoover would forever blame Roosevelt and the Democratic Congress for spoiling his hard-earned recovery, an argument that has only recently gained currency among economists.

And:

Alarmed at these threats to recovery, Hoover pushed Democratic congressional leaders and the incoming administration for action. He wanted to cut federal spending, reorganize the executive branch to save money, reestablish the confidentiality of RFC loans, introduce bankruptcy legislation to protect foreclosures, grant new powers to the Federal Reserve, and pass new banking regulation, including measures to protect depositors … He was frustrated at every turn by Democratic leadership taking cues from the President-Elect … On February 5, Congress took the obstructionism a degree further by closing shop with 23 days left in its session.

In mid-February, there is another run on the banks, worse than all the other runs on the banks thus far. Hoover asks Congress to do something – Congress says they will only listen to President-Elect Roosevelt. Hoover writes a letter to Roosevelt begging him to give Congress permission to act, saying it is a national emergency and he has to act right now. Roosevelt refuses to respond to the letter for eleven days, by which time the banks have all failed.

Then, a month later, he stands up before the American people and says they have nothing to fear but fear itself – a line he stole from Hoover – and accepts their adulation as Destined Savior. He keeps this Destined Savior status throughout his administration. In 1939, Roosevelt still had everyone convinced that Hoover was totally discredited by his failure to solve the Great Depression in three years – whereas Roosevelt had failed to solve it for six but that was totally okay and he deserved credit for being a bold leader who tried really hard.

So how come Hoover bears so much of the blame in public consciousness? Whyte points to three factors.

First, Hoover just the bad luck of being in office when an international depression struck. Its beginning wasn’t his fault, its persistence wasn’t his fault, but it happened on his watch and he got blamed.

Second, in 1928 the Democratic National Committee took the unprecedented step of continuing to exist even after a presidential election. It dedicated itself to the sort of PR we now take for granted: critical responses to major speeches, coordinated messaging among Democratic politicians, working alongside friendly media to create a narrative. The Republicans had nothing like it; the RNC forgot to exist for the 1930 midterms, and Hoover was forced to personally coordinate Republican campaigns from his White House office. Although Hoover was good (some would say obsessed) at reacting to specific threats on his personal reputation, the idea of coordinating a media narrative felt too much like the kind of politics he felt was beneath him. So he didn’t try. When the Democrats launched a massive public blitz to get everyone to call homeless encampments “Hoovervilles”, he privately fumed but publicly held his tongue. FDR and the Democrats stayed relentlessly on message and the accusation stuck.

And third, Hoover was dead-set against welfare. However admirable his attempts to reverse the Depression, stabilize banking, etc, he drew the line at a national dole for the Depression’s victims. This was one of FDR’s chief accusations against him, and it was entirely correct. Hoover knew that going down that route would lead pretty much where it led Roosevelt – to a dectupling of the size of government and the abandonment of the Constitutional vision of a small federal government presiding over substantially autonomous states. Herbert Hoover, history’s greatest philanthropist and ender-of-famines, would go down in history as the guy who refused to feed starving people. And they hated him for it.

Scott Alexander, “Book Review: Hoover”, Slate Star Codex, 2020-03-17.

May 10, 2025

QotD: Undocumented America

In the Panopticon State, the Shadowlands are thriving: a state that presumes to tax and license Joe Schmoe for using the table in the corner of his basement as a home office apparently doesn’t spot the half-dozen additional dwellings that sprout in José Schmoe’s yard out on the edge of town. Do-it-yourself wiring stretches from bungalow to lean-to trailer to RV to rusting pick-up on bricks, as five, six, eight, twelve different housing units pitch up on one lot. The more Undocumented America secedes from the hyper-regulatory state, the more frenziedly Big Nanny documents you and yours.

This multicultural squeamishness is most instructive. Illegal immigrants are providing a model for survival in an impoverished statist America, and on the whole the state is happy to let them do so. In Undocumented America, the buildings have no building codes, the sales have no sales tax, your identity card gives no clue as to your real identity. In the years ahead, for many poor Overdocumented-Americans, living in the Shadowlands will offer if not the prospect of escape then at least temporary relief. As America loses its technological edge and the present Chinese cyber-probing gets disseminated to the Wikileaks types, the blips on the computer screen representing your checking and savings accounts will become more vulnerable. After yet another brutal attack, your local branch never reconnects to head office; it brings up from the vault the old First National Bank of Deadsville shingle and starts issuing fewer cards and more checkbooks. And then fewer checkbooks and more cash. In small bills.

The planet is dividing into two extremes: an advanced world — Europe, North America, Australia — in which privacy is vanishing and the state will soon be able to monitor you every second of the day; and a reprimitivizing world — Somalia, the Pakistani tribal lands — where no one has a clue what’s going on. Undocumented America is giving us a lesson in how Waziristan and CCTV London can inhabit the same real estate, like overlapping area codes. There will be many takers for that in the years ahead. As Documented America fails, poor whites, poor blacks, and many others will find it easier to assimilate with Undocumented America, and retreat into the shadows.

Mark Steyn, After America, 2011.

May 1, 2025

When “looming dystopia” is the preferable scenario

Elizabeth Nickson on just how badly the great and the powerful have managed to screw up so badly that instead of opening for Anthrax at the Hollywood Bowl, “Looming Dystopia” might actually be one of the better possible futures we face:

I asked Grok to show me Looming Dystopia opening for Anthrax. This is the “in Gothic style” version.

I am a person of faith, of Christ, not a very good one, but one who has been devoted for a long time. I’m not saying I didn’t spend twenty years in the great big glittering world, where I indulged every whim, lived among the powerful, beautiful, God- hostiles, adopted their habits of speech and dress, went to every small exquisite museum, the play of the moment, the art openings, the restaurants and parties, became a sophisticate able to live within that world as handmaiden or companion. I mean, for almost ten of those years, I had a husband who never, not once, came home without a present. But even that came of prayer, of a desire fulfilled a wish granted, of prayer, as in “You want this? Ok then, you will sicken, but here it is”.

That world – the enrichment of culture that came out of the 80’s and 90’s – determines today. That life is the model and goal for many and in fact, now the design, the plan laid out by those who plan the future of the world. Humans shunted deliberately into city life, then enhanced via surgery and chip. Indulgence, consumption, fighting for preference, ambition. Cultural creatives, unmarried, oddly-sexed, politically left would determine the future, their gifts the siren call of the arts, fashion, grand bohemia, Hollywood, eat, drink and travel merrily. The end goal of life: your individuality, your woundedness, your self care, the full expression of your specific gifts. If you are lucky you too can be Lady GaGa or BlackPink and have stadiums roar when you appear. Other humans? The state will take care of them, do not worry. Maybe they will die off. Like dinosaurs.

The central banks have gamed this going forward, making the insane assumption that this social movement was permanent. Did they depend on feminism and drugs to stop the next step, ie, young people leaving the city to build families? Even if they did, they thought they could stop it. Why? Because fascist greens like John Kerry, told them that rural regions must be left to “recover”.

Therefore they gutted the suburbs of financing, because “poor land use”, and “too much car required”, which is preposterous in the Americas with all this land. What else does a young family want but trees and parks, and lawns and a neighborhood of friends, not riven with whores, crackheads and murderous migrants?

The ‘08 crash was predicated on Thatcher’s fiscal success in selling people their council houses in the 80’s. Wonderful! thought Bill Clinton’s team, let’s lead marginal Americans into housing, and lo, we still haven’t paid the freight for that insane idea. I had a paralegal friend in Florida who was foreclosing on $500,000 loans to actual crackhead whores. Clinton’s people, lost in their greed and benevolence, forgot that the British council estate dweller was homogenous, placed, as in deep roots in the area, and stable. In the U.S and Canada, idiot banks lent to just about any joker who turned up with a plausible story. Then the speculators invaded, everyone cashed out merrily, then ka-boom. And pioneering walking away with $100 million from government “service” was Jimmy Johnson, Head of Fannie Mae.

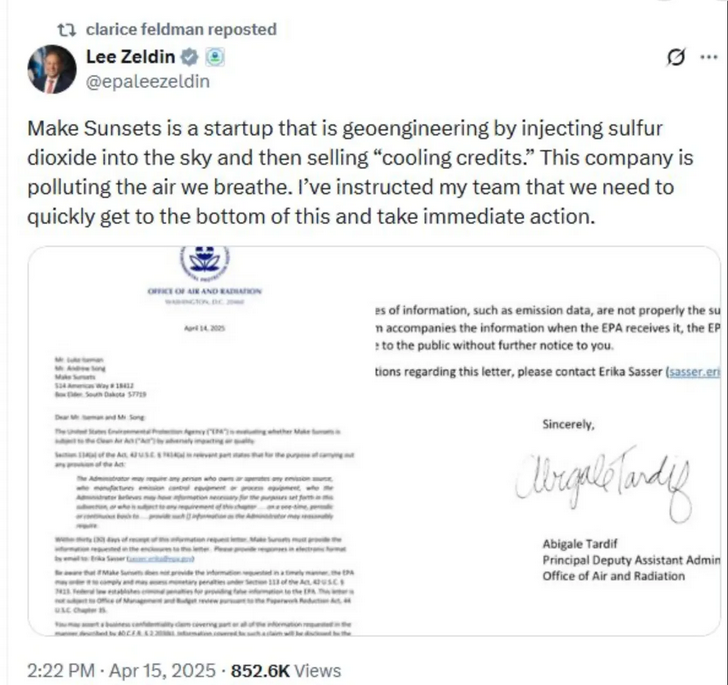

I mean, it’s stupid. The western world’s current bankruptcy (and it’s severe) was caused by Central Bank clowns. Those ridiculous, repellent, hideously expensive COP #8,789 conferences had two outcomes: banks would be compelled to lend to green, require green, require climate mitigation, and jump through DEI, ESG hoops, and governments would chunk up green regs. And prosperity would bloom! Not only that, they surreptitiously, across the world, funded actual companies that poisoned the air, water and land. And when I say “they funded”, I mean the taxpayer did. A lot of our money went into insane outfits like this:

And just like Malcom Gladwell’s tipping point – it took ten years – boom, economic activity came to a screeching halt, except for the wreckage of green energy enterprises everywhere, government debt and re-financing. For instance, the Obama-created outfit, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, that consists of three solar concentrating thermal power plants in California burned through $1 billion before it collapsed in February. It is one of thousands across the west, all subsidized by the taxpayer. Unwittingly. The press is so embarrassed, they don’t report the trillions lost to green energy projects.

Again, the central bankers own this.

Central bankers have become a metastatic cancer on the economy. By definition, they are late adopters on the marketing curve. By the time they notice something and make their plans upon it, it’s over and something new is growing. Today, the mega-cities everywhere are emptying of everyone over 30 with an income, even or rather especially in China, where the young have just said … nope, a pox on your Commie plans. Chinese, European, British, American, everyone is trickling back to the towns of which their ancestral memories sing, where they can root, where they can live smaller, without environmental toxicity, the rank depravity of the super-culture, the ruinous stupidity of green. The great cities are now super-dangerous for women, and that is spreading as the autocrats in power force violent young men into towns. Last week a young woman in Vancouver fought off a migrant who tried to kill her three times in Stanley Park. My modest, Christian, pioneer family who built the early city along with their community of 10,000 and neglible government, made that park in the early 1900’s; my great grandmother was the first woman to ride a bike in bloomers through that park. It was so safe for 100 years you could let kids play in it after dark, calling them home with a whistle. It is one of the world’s great urban parks, more astonishing than Central Park. This is an outright tragedy. And it is unnoticed, unreported, except on TikTok.

April 16, 2025

Government freezes the bank account of a PPC candidate, gives no reasons

The federal government had the banks freeze the accounts of a large number of Freedom Convoy supporters back in 2022 … without any legal justification. The courts failed to act in protection of ordinary Canadians so the feds are at it again, in this case freezing the bank account of a PPC candidate in the current election:

I still hadn’t completely given up on the country, and with an election pending, I saw one last opportunity to fight for change, and to force some conversations that had been suppressed in my progressive Vancouver East riding. Last month, I decided to run as a Canadian Member of Parliament, and began to publicize my decision to run for the People’s Party of Canada (PPC) — the only party truly committed to fighting for freedom and women’s sex-based rights.

My candidacy was confirmed officially on Tuesday. That same day, I tried to access my bank account and could not. I contacted my bank, Vancity, and was informed the account had been frozen as per direction from the government. I had accessed my account just two days prior, so the timing was clear. I had not been informed of this freezing by anyone — not the bank, not the government. No one attempted to contact me. I was completely blindsided.

When I contacted my bank they refused to give me any information beyond the fact they were following government orders, and they gave me a number and name to contact. I called the number, and got a voicemail saying the employee was on vacation all week. So basically this guy froze my bank account and immediately went on vacation.

His voicemail offered another extension to call, which I did. No one answered, so I left a message. I called again later that day and left another message. No one returned my call, so I called back the next day and left another message. Still no one returned my call. The following day I called again and received a message saying I could not get through on account of “technical difficulties”. I tried calling a general number, and asked the woman on the other end of the phone if she could please refer me to someone who could provide me with information about why my bank account was frozen. She told me, “I can’t give you any information unless you give me more information about what’s going on,” to which I responded, “I have no information, that’s why I’m calling you: to get information”. We went back and forth like this for a while until I asked her if she was retarded and then said, “What exactly is your job — what is it you are being paid to do with the tax dollars of Canadians”. She explained her job was to refer people who called to the appropriate departments, numbers, and individuals. “Ok,” I said. “Then can you please refer me to someone who can explain to me what is going on with my bank account.” She said “No,” and I hung up.

It has now been a week since my bank account was frozen and I have received zero communication or information from the government.

I had a flight booked back to Canada today, which I cancelled, because if my bank account is frozen I can’t operate in the country and because I am very concerned about what awaits me upon arrival. I decided it wasn’t worth the risk of persecution or attempted prosecution so will not be returning to Canada, despite my original intention to come back to campaign.

I am completely appalled that this is how the Canadian government treats its citizens, accountability-free. It is unacceptable and reprehensible to freeze the bank accounts of Canadians, leaving them potentially starving, homeless, and unable to survive — EVER, never mind without contacting them, communicating with them, or providing them with any information.

I cannot help but note that the timing of all this is incredibly sketchy, and so my suspicion is that I am being targeted for political reasons, and that the government is attempting to find an excuse to criminalize me, as well as to punish me generally on account of my continued criticisms of the ruling Liberal party.

It also worth noting that the freezing of my bank account at this precise moment constitutes election interference, as I am now prevented from returning to Canada to campaign in my riding.

I knew things were bad in Canada — they have been moving in a terrifying direction for years, and yet far too many Canadians refuse to take their heads out of the sand and see that they are living under an increasingly authoritarian, punitive, evil government, never mind push back against this tyranny.

Canadians are mere weeks away from having their rights and freedoms completely disappeared, yet many remain in hysterics about Donald Trump and an electric vehicle company owned by an American man who has zero impact on the lives of regular Canadians.

I am lucky to have a platform where I can speak up about these things — many Canadians don’t, and the government will therefore easily get away with doing whatever they like to their citizens, accountability-free, knowing most regular Canadians are left without recourse.

This government is sick. Things are not fine. Things are very bad. And if Canadians don’t wake up now, en masse, things will undoubtedly get worse.

February 10, 2025

Trump’s EO against central bank digital currencies

The Trudeau government’s illegal move to freeze the bank accounts of Canadians who supported the Freedom Convoy should have clearly illustrated the dangers of allowing a government to exercise that level of control over individuals’ financial affairs. (It’s hard to express just how inhumane that move was to deprive thousands of Canadians their ability to conduct any financial business at all … in the middle of the winter just because they’d chipped in small donations to a cause Trudeau didn’t like.) I don’t know if Donald Trump took note, but another of his long list of executive orders directly addresses crypto and CBDCs:

“Bitcoin – from WSJ” by MarkGregory007 is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While the order has upsides and downsides concerning current crypto policies, the parts of the order I’m most excited about are the portions on Central Bank Digital Currencies, or CBDCs. A CBDC is essentially a government-created centrally controlled version of cryptocurrency. As FEE has discussed in the past, CBDCs are a very dangerous idea, and it was troubling that they were being pursued by the Biden administration.

So what does the Trump executive order say about them? Take a look:

[The Trump administration is] taking measures to protect Americans from the risks of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), which threaten the stability of the financial system, individual privacy, and the sovereignty of the United States, including by prohibiting the establishment, issuance, circulation, and use of a CBDC within the jurisdiction of the United States.

Section 5 of the order covers how this will be done. By the order, it’s now illegal for bureaucrats within government agencies to pursue any plans to establish a CBDC unless it is required by law. In other words, barring the possibility that some bureaucrats could break the law, CBDC initiatives must immediately end unless the legislature passes bills requiring them.

This is a big step because the establishment of a CBDC would require significant political, bureaucratic, and technological infrastructure to be implemented. Trump’s order puts a pause on the building of that infrastructure which began under Biden.

On net, Trump’s order seems to have been taken well by crypto markets, with Bitcoin seeing a small price surge after the announcement of the order. So while the future of government crypto regulation remains unclear, the new administration’s commitment to stopping CBDCs and protecting the rights of those engaging in crypto mining and transactions seems to be a good sign.

January 19, 2025

Mark Carney is a serious man … that doesn’t mean he’d be a good political leader

The Line‘s Jen Gerson likes Mark Carney, but she hastens to add that this isn’t necessarily good news for Mr. Carney as she felt the same way about Jim Prentice who was very briefly Premier of Alberta but “demonstrated the political nous of a chicken nugget” and quickly was out of power:

Then-Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

WEF photo via Wikimedia Commons.

I learned the most valuable lesson from that period of political reporting, one I try to carry with me unto this very day: Never, never let one’s personal feelings about an individual candidate corrupt one’s political analysis. And if you think about it, this is a very important lesson to learn.

I am not a normal person. That which appeals to me is very unlikely to find purchase with sane, feeling voters who hold ordinary jobs and live lives filled with meaningful human connections and real, not-political conversations.

I was thinking about this as I watched Mark Carney announce his intention to run as Liberal leader in Edmonton on Thursday. Carney is a serious man. He has a real CV and a long list of meaningful accomplishments. He’s a man who seems to understand that the “good old times are over”. He’s a man who has navigated several international crises — as he was keen to point out. He’s a man who despises the excesses of both the right and the left. He’s a man who is is focused on building Canada’s economy.

He’s a man who has correctly identified one of the Conservatives’ core weaknesses, their tendency to channel legitimate anger and grievance into thin slogans that offer few substantive plans toward the kinds of significant changes that this country will be required to make. The fact that Carney is making this critique while coming to the fore without offering any substantive plans of his own is only to be expected considering the timeline’s he’s working with, I suppose.

Regardless, Carney is giving Jim Prentice Energy. Jean Charest Energy. Jeb! Energy.

I like him.

[…]

For that matter, if Carney wants to present himself as a strong supporter of Canada, a defender of our sovereignty in the face of America’s re-articulated expansionist ambitions, why did he preempt his leadership launch with an appearance on The Daily Show? What message are we to take from this: that Carney is well liked and respected by the American political milieu that was roundly trounced by Donald Trump?

It doesn’t signal a lot of faith in Canada as a cohesive cultural concept to soft launch your political leadership campaign through a marshmallow chat with an American comedy host. (As an aside, I realize that foreigners aren’t real to Americans, but I’m begging literally any television journalist on a mainstream U.S. network to stop treating our politicians like kawaii pets [Wiki] on loan from a northern Democrat utopia that exists only in their minds. These people can handle hard questions — even about matters that are important to an American audience; like, for example, Canada’s delinquent NATO spending.)

Did Mark Carney not believe that the CBC that I presume he will be campaigning to preserve was up to the challenge of doing the first interview with him? Look, I wouldn’t turn down a chat at Jon Stewart’s table if I got the call, but if the best possible way to reach potential Liberal leadership voters in 2025 is to pop onto American TV, we might as well pack it in, call ourselves 51 and be done with it.

By the way, in case anyone hasn’t yet pointed it out; the average age of a Daily Show audience member is 63. The audience is in steep decline, and it doesn’t even air on any Canadian TV channels anymore. To watch the Carney clip, Canadians have to seek it out on Apple TV or YouTube. Usually the day after because the target demo is usually in bed by 9 p.m. MST now.

December 24, 2024

David Friedman on elegant solutions to problems

Sometimes the solution to a problem is obvious … at least once someone else has pointed it out:

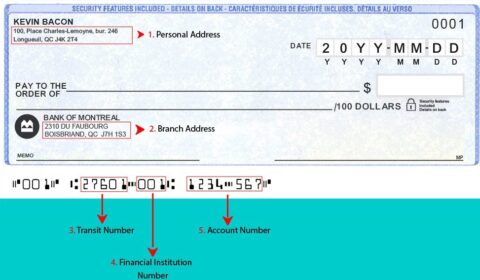

Recently, when writing a check, it occurred to me that requiring the amount to be given separately in both words and number was a simple and ingenious solution to the problem of reducing error. It is possible, if your handwriting is as sloppy as mine, to write a letter or number that can be misread as a different letter or number. If redundancy consisted of writing the amount of the check twice as numbers or twice as words the same error could appear in both versions. It is a great deal less likely to make two errors, one in letters and one in numbers, that happen to produce the same mistaken result. It reduces the risk of fraud as well, for a similar reason.

That is one example of a simple and elegant solution to a problem, so simple that until today it had never occurred to me to wonder why checks were written that way. Another example of the same pattern is a nurse or pharmacist checking both your name and date of birth to confirm your identity.1

That started me thinking about other examples:

The design of rubber spatulas, one bottom corner a right angle, the other a quarter circle. One of the uses of the device is to scrape up the contents of containers, jars and bowls and such. Some containers have curved bottoms, some flat bottoms at a right angle to the wall. The standard design fits both.

Manhole covers are round because it is the one simple shape such that there is no way of turning it that lets it fall through the hole it fits over.

Consider an analog meter with a needle and a scale behind it. If you read it at a slight angle you get the reading a little high or low. Add a section of mirror behind the needle and line up the image behind the needle. Problem solved.

If you try to turn a small screw with a large screwdriver it doesn’t fit into the slot. Turning a large screw with a small screwdriver isn’t always impossible but if the screw is at all tight you are likely to damage the screwdriver doing it. The solution is the Phillips screwdriver. The tip of a large Phillips screwdriver is identical to a smaller one so can be used on a range of screw sizes.2

Ziplock bags have been around since the sixties. Inventing them was not simple but a new application is: packaging that consists of a sealed plastic bag with a Ziplock below the seal. After you cut open the bag you can use the ziplock to keep the contents from spilling or drying. I do not know how recent an innovation it is but I cannot recall an example from more than a decade ago.

1. This one and some of the others were suggested by posters on the web forum Data Secrets Lox.

2. I am told that the solution is not perfect, doesn’t work for very small screws, which require a smaller size of driver.

QotD: The real hero of It’s A Wonderful Life

@BillyJingo

I get the feeling you’re the kind of guy who secretly rooted for Mr Potter.@Iowahawkblog

George Bailey: whines for a public bailout of his grossly mismanaged financial institutionMr Potter: reinvigorates boring small town by developing exciting nightlife district

David Burge (@Iowahawkblog), Twitter, 2022-11-16.

December 12, 2024

The Canada Post strike is achieving one thing … strangling the use of cheques

In The Line, Phil A. McBride outlines the one palpable achievement of the postal workers’ strike in the likely fatal blow to the use of paper cheques in Canada:

For more than a century, Canadian businesses have been using cheques and the post office to send and receive money across the country and the world. It’s easy: you write a cheque, you put it in the mail, the recipient deposits the cheque at their bank, you wait five business days for it to clear and voila — you’ve got the money.

Except, right now, of course, that’s not happening, due to the ongoing postal strike. In fact, a great number of cheques that are in the mail are stuck there, leaving businesses and Canadians with money stranded in transit. I am increasingly convinced that this strike will be remembered in the future as the death of cheques in Canada, at least as a major medium of business exchange.

The banks won’t miss cheques, if so. Cheques are expensive. In 2015, Scotiabank estimated that the writing and processing of a cheque cost anywhere between $9 and $25. In 2023, approximately 379 million cheques were issued for a combined value of $2.9 trillion dollars. That’s an average value of $7,650.00 per cheque, at an averaged cost of $6.44 billion dollars to the banks and their customers. Very little of that cost is incurred if a payment is made electronically.

But it’s not just the money. Cheques are prone to fraud. Cheques can be counterfeited, signatures can be forged and cheques can be written against accounts that can’t cover the amount they’re issued for. The customer is responsible for sending and receiving them, which means they are prone to loss or interception, which adds further time and cost to an already expensive process.

As a business owner, I happen to agree with the banks: I don’t like cheques. I’m made to wait five business days to access my money, and that’s after I’ve waited for the client to issue the cheque and for the postal service to (once upon a time) deliver it to my office.

Today, all of Canada’s charter banks, as well as most Credit Unions, offer many options for electronic payment. Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT), Interac Electronic Money Transfer (EMT), debit cards, credit cards, even SWIFT wire transfers for international payment. All of these institutions have the ability allow for multiple layers of approval that satisfy corporate accounting, security and reporting requirements. All of these forms of payment are faster, cheaper and more secure than cheques — in most cases, I get access to my money inside 24 hours, rather than waiting for a full week for a cheque to clear.

So why has the cheque endured as long as it has?

Some combination of “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” and “It’s always been done this way”.

October 12, 2024

Canadians don’t hate their banks enough

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte follows up on an earlier item thanks to the many Canadians who responded with their own tales of woe in their dealings with Canadian banks:

Since I mentioned a couple of weeks ago that we have published Andrew Spence’s Fleeced: Canadians Versus Their Banks, the latest edition of Sutherland Quarterly, I’ve been inundated with people’s horror stories of their dealings with Canada’s chartered banks. Jack David’s tale in the above interview is a classic of the genre.

In Fleeced, Andrew lays out in aggravating detail how Canadian banks, although chartered by the federal government to facilitate economic activity in the broader economy, do all they can to avoid lending to small and medium businesses, never mind that small and medium businesses employ two-thirds of our private-sector labour force and account for half of Canada’s gross domestic product.

By OECD standards, small businesses in Canada are starved of bank credit, and when they are able to secure a loan, they pay through the nose. The spread between interest rates on loans to small businesses and large businesses in Canada is a whopping 2.48 percent, compared to .42 percent in the US — more than five times higher.

Why? Because Canada’s banks are a tight little oligopoly, impervious to meaningful competition. Their cozy situation allows them to be exceedingly greedy. Their profits and returns to shareholders are wildly beyond those of banks in the US and UK (and, as Andrew demonstrates, their returns from their Canadian operations are far in excess of those from the US market, meaning they screw the home market hardest.)

Our banks never miss an opportunity to impose a new fee, or off-load risk. From their perspective, small business involves too much risk — some of them will inevitably fail. The banks prefer that publishers and dry-cleaners and restaurateurs either finance themselves by pledging their homes, or use their credit cards to cover fluctuations in cash flow or make investments that will help them hire, expand, and grow. And that’s what entrepreneurs do. According to a survey by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, only one in five respondents accessed a bank loan or line of credit. Half of respondents financed themselves, tapped existing equity and personal lines of credit, and about 30 percent used their high-interest credit cards.

By severely rationing credit and making it exceedingly expensive, Canada’s banks siphon off an ungodly share of entrepreneurial profit to themselves while leaving the entrepreneur with all the risk. Their insistence on putting their own profits above service to the Canadian economy is one of the main reasons Canada has such a slow-growing, unproductive economy and a stagnant standard of living.

There is much else in this slim volume to make your blood boil: exorbitant fees on chequing and savings accounts; mutual fund expenses that torpedo investments; ridiculous mortgage restrictions, infuriating customer service …

Fleeced: Canadians Versus Their Banks is a stunning exposé of the inner workings of our six major banks — something only a reformed banker and financial services veteran such as Andrew could write. He also explodes the myth that a bloated, uncompetitive banking sector is the price we have to pay for stability in times of financial crisis.

We are in desperate need of banking reform in Canada. Read this book and you’ll be shouting at your member of Parliament for prompt action.