The foundation for most modern thinking about this topic begins with Mao Zedong’s theorizing about what he called “protracted people’s war” in a work entitled – conveniently enough – On Protracted War (1938), though while the Chinese Communist Party would tend to subsequently represent the ideas there are a singular work of Mao’s genius, in practice he was hardly the sole thinker involved. The reason we start with Mao is that his subsequent success in China (though complicated by other factors) contributed to subsequent movements fighting “wars of national liberation” consciously modeled their efforts off of this theoretical foundation.

The situation for the Chinese Communists in 1938 was a difficult one. The Chinese Red Army has set up a base of power in the early 1930s in Jiangxi province in South-Eastern China, but in 1934 had been forced by Kuomintang Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai-shek to retreat, eventually rebasing over 5,000 miles away (they’re not able to straight-line the march) in Shaanxi in China’s mountainous north in what became known as The Long March. Consequently, no one could be under any illusions of the relative power of the Chiang’s nationalist forces and the Chinese Red Army. And then, to make things worse, in 1937, Japan had invaded China (the Second Sino-Japanese War, which was a major part of WWII), beating back the Nationalist armies which had already shown themselves to be stronger than the Communists. So now Mao has to beat two armies, both of which have shown themselves to be much stronger than he is (though in the immediate term, Mao and Chiang formed a “United Front” against Japan, though tensions remained high and both sides expected to resume hostilities the moment the Japanese threat was gone). Moreover, Mao’s side lacks not only the tools of war, but the industrial capacity to build the tools of war – and the previous century of Chinese history had shown in stark terms how difficult a situation a non-industrial force faced in squaring off against industrial firepower.

That’s the context for the theory.

What Mao observed was that a “war of quick decision” would be one that the Red Army would simply lose. Because he was weaker, there was no way to win fast, so trying to fight a “fast” war would just mean losing. Consequently, a slow war – a protracted war – was necessary. But that imposes problems – in a “war of quick decision” the route to victory was fairly clear: destroy enemy armed forces and seize territory to deny them the resources to raise new forces. Classic Clausewitzian (drink!) stuff. But of course the Red Army couldn’t do that in 1938 (they’d just lose), so they needed to plan another potential route to victory to coordinate their actions. That is, they need a strategic framework – remember that strategy is the level of military analysis where we think about what our end goals should be and what methods we can employ to actually reach those goals (so that we are not just blindly lashing out but in fact making concrete progress towards a desired end-state).

Mao understands this route as consisting of three distinct phases, which he imagines will happen in order as a progression and also consisting of three types of warfare, all of which happen in different degrees and for different purposes in each phase. We can deal with the types of warfare first:

- Positional Warfare is traditional conventional warfare, attempting to take and hold territory. This is going to be done generally by the regular forces of the Red Army.

- Mobile Warfare consists of fast-moving attacks, “hit-and-run”, performed by the regular forces of the Red Army, typically on the flanks of advancing enemy forces.

- Guerrilla Warfare consists of operations of sabotage, assassination and raids on poorly defended targets, performed by irregular forces (that is, not the Red Army), organized in the area of enemy “control”.

The first phase of this strategy is the enemy strategic offensive (or the “strategic defensive” from the perspective of Mao). Because the enemy is stronger and pursuing a conventional victory through territorial control, they will attack, advancing through territory. In this first phase, trying to match the enemy in positional warfare is foolish – again, you just lose. Instead, the Red Army trades space for time, falling back to buy time for the enemy offensive to weaken rather than meeting it at its strongest, a concept you may recall from our discussions of defense in depth. The focus in this phase is on mobile warfare, striking at the enemy’s flanks but falling back before their main advances. Positional warfare is only used in defense of the mountain bases (where terrain is favorable) and only after the difficulties of long advances (and stretched logistics) have weakened the attacker. Mobile warfare is supplemented by guerrilla operations in rear areas in this phase, but falling back is also a key opportunity to leave behind organizers for guerrillas in the occupied zones that, in theory at least, support the retreating Red Army (we’ll come back to this).

Eventually, due to friction (drink!) any attack is going to run out of steam and bog down; the mobile warfare of the first phase is meant to accelerate this, of course. That creates a second phase, “strategic stalemate” where the enemy, having taken a lot of territory, is trying to secure their control of it and build new forces for new offensives, but is also stretched thin trying to hold and control all of that newly seized territory. Guerrilla attacks in this phase take much greater importance, preventing the enemy from securing their rear areas and gradually weakening them, while at the same time sustaining support by testifying to the continued existence of the Red Army. Crucially, even as the enemy gets weaker, one of the things Mao imagines for this phase is that guerrilla operations create opportunities to steal military materiel from the enemy so that the factories of the industrialized foe serve to supply the Red Army – safely secure in its mountain bases – so that it becomes stronger. At the same time (we’ll come back to this), in this phase capable recruits are also be filtered out of the occupied areas to join the Red Army, growing its strength.

Finally in the third stage, the counter-offensive, when the process of weakening the enemy through guerrilla attacks and strengthening the Red Army through stolen supplies, new recruits and international support (Mao imagines the last element to be crucial and in the event it very much was), the Red Army can shift to positional warfare again, pushing forward to recapture lost territory in conventional campaigns.

Through all of this, Mao stresses the importance of the political struggle as well. For the guerrillas to succeed, they must “live among the people as fish in the sea”. That is, the population – and in the China of this era that meant generally the rural population – becomes the covering terrain that allows the guerrillas to operate in enemy controlled areas. In order for that to work, popular support – or at least popular acquiescence (a village that doesn’t report you because it supports you works the same way as a village that doesn’t report you because it hates Chiang or a village that doesn’t report you because it knows that it will face violence reprisals if it does; the key is that you aren’t reported) – is required. As a result both retreating Red Army forces in Phase I need to prepare lost areas politically as they retreat and then once they are gone the guerrilla forces need to engage in political action. Because Mao is working with a technological base in which regular people have relatively little access to radio or television, a lot of the agitation here is imagined to be pretty face-to-face, or based on print technology (leaflets, etc), so the guerrillas need to be in the communities in order to do the political work.

Guerrilla actions in the second phase also serve a crucial political purpose: they testify to the continued existence and effectiveness of the Red Army. After all, it is very important, during the period when the main body of Communist forces are essentially avoiding direct contact with the enemy that they not give the impression that they are defeated or have given up in order to sustain will and give everyone the hope of eventual victory. Everyone there of course also includes the main body of the army holed up in its mountain bases – they too need to know that the cause is still active and that there is a route to eventual victory.

Fundamentally, the goal here is to make the war about mobilizing people rather than about mobilizing industry, thus transforming a war focused on firepower (which you lose) into a war about will – in the Clausewitzian (drink! – folks, I hope you all brought more than one drink for this …) sense – which can be won, albeit only slowly, as the slow trickle of casualties and defeats in Phase II steadily degrades enemy will, leading to their weakness and eventual collapse in Phase III.

I should note that Mao is very open that this protracted way of war would be likely to inflict a lot of damage on the country and a lot of suffering on the people. Casualties, especially among the guerrillas, are likely to be high and the guerrillas own activities would be likely to produce repressive policies from the occupiers (not that either Chiang’s Nationalists of the Imperial Japanese Army – or Mao’s Communists – needed much inducement to engage in brutal repression). Mao acknowledges those costs but is largely unconcerned by them, as indeed he would later as the ruler of a unified China be unconcerned about his man-made famine and repression killing millions. But it is important to note that this is a strategic framework which is forced to accept, by virtue of accepting a long war, that there will be a lot of collateral damage.

Now there is a historical irony here: in the event, Mao’s Red Army ended up not doing a whole lot of this. The great majority of the fighting against Japan in China was positional warfare by Chiang’s Nationalists; Mao’s Red Army achieved very little (except preparing the ground for their eventual resumption of war against Chiang) and in the event, Japan was defeated not in China but by the United States. Japanese forces in China, even at the end of the war, were still in a relatively strong position compared to Chinese forces (Nationalist or Communist) despite the substantial degradation of the Japanese war economy under the pressure of American bombing and submarine warfare. But the war with Japan left Chiang’s Nationalists fatally weakened and demoralized, so when Mao and Chiang resumed hostilities, the former with Soviet support, Mao was able to shift almost immediately to Phase III, skipping much of the theory and still win.

Nevertheless, Mao’s apparent tremendous success gave his theory of protracted war incredible cachet, leading it to be adapted with modifications (and variations in success) to all sorts of similar wars, particularly but not exclusively by communist-aligned groups.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: How the Weak Can Win – A Primer on Protracted War”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-03-03.

December 6, 2022

QotD: Mao Zedong’s theory of “Protracted War”

November 25, 2022

Our old, comfortable geopolitical certainties are becoming less comfortable and less certain

In The Line, Matt Gurney discusses a few of the things he heard at the recent Halifax International Security Forum:

First, though, I wanted to explore that grim feeling that swept over me as Forum president Peter Van Praagh stepped up to the lectern and opened the formal proceedings with a review of the geopolitical situation, and how we got here.

From his prepared remarks (slightly trimmed):

Last year … we marked the 20th anniversary of 9/11. It was not an auspicious anniversary. Just months earlier, the United States and its allies withdrew their troops from Afghanistan and discarded the hopes and dreams of so many Afghans … [it] was a low point for Afghanistan and indeed, for all of us. … It was the culmination of 20 years of good intentions. And bad results:

The decisions made in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, North Korea going nuclear, Russia’s invasion of Georgia, the Great Recession, Iran, the Arab Spring and the Syrian civil war, the surge of refugees — more than at any time in human history, the successful rise of populist politics, the higher than necessary death toll from coronavirus, Hong Kong losing its freedoms, January 6 and its wake, climate-change disasters, and our withdrawal from Afghanistan …

It was a tragic end to a 20-year tragic era.

That’s a pretty depressing list. Right?

As a student of history, I always strive to avoid too much recency bias. Most of the things you hear described as “unprecedented” aren’t anything remotely close to that. The general public has a memory of a few years — maybe a generation. We definitely do face some novel challenges today, but we are still better off than most generations in human history, and it’s not even close.

Still. Van Praagh offered a bleak if concise catalogue of tragedy and struggle. And there are some notable absences. The Iraq War, for instance, is probably worth noting as a specific event, not just part of the Sept. 11th fallout. Perhaps the Libyan intervention as well. Some of China’s more aggressive actions, especially at home, also come to mind.

But as I mulled over that terse version of early-21st-century history, something else jumped out at me: most of those threats were things that happened far away and to other people.

I mentioned recency bias above, so it’s only fair to note a different bias: “far away” and “other people” depends on the vantage point, doesn’t it? Every event listed above was a direct and local tragedy for the people caught in the middle of it, who don’t have the luxury of viewing these events at a comfortable remove, the way the West generally has.

The pandemic, of course, did not spare the West. Nor did the Great Recession, the toll of a changing climate and the populist upheavals roiling the democracies. Those are local problems for us all.

The military challenges, though, are getting more and more local, aren’t they? North Korea seemed far away once; today it’s using the Pacific Ocean’s vital sealanes for target practice and providing some of the munitions being used against civilians in Europe. Libya, Syria and the other migration crises posed real societal and political challenges for Europe, but nothing like what the continent has been bracing for in the event of either crippling energy shortages or an outright escalation into a military conflict, potentially nuclear conflict, with Russia. China’s growing ambitions and willingness to use force pose direct challenges to the West and its prosperity; American financier Ken Griffin recently made the headlines when he observed that if Chinese military action were to cut off or disrupt American access to Taiwanese semiconductor chips, the immediate impact on the U.S. economy would be between five and 10 per cent of GDP. That would be a Great Depression-sized bodyblow, and it could happen almost instantly and without much warning.

Pondering Van Praagh’s list later on, it occurred to me that the more remote threats to core Western security and economic interests were also more remote in time. The closer Van Praagh’s summation of crises came to the present, the more immediate and near to us they became.

November 2, 2022

QotD: Being “the world’s policeman”

The British spent most of the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries as the world’s policeman, responsible for keeping the peace, and for maintaining a balance of power. They were usually pilloried by all about them for this role, particularly by up and coming powers who wanted a “place in the sun” — Germany and the United States being the stand-out examples (though there is a lot of whinging from old allies like Russia). For the last half of that period, the British voter was having serious second thoughts about the whole concept.

The United States took on the mantle of world’s policeman in the post-Second World War world. They have spent much of the last 60 years trying to keep the peace, and, interestingly, to maintain the balance of power. (Do not be fooled by the concept of the overwhelming superpower. Britain was a lot closer to being able to take on the rest of the world in the 19th century, when it really could defeat every other navy in the world combined; than the US is now, where it could perhaps face Iran, Russia and India simultaneously, as long as the European Union is friendly. Whoops, forgot China, the Balkans, Palestine, Syria, North Korea, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and other little blips on the US horizon. Well let’s be honest, no one has ever been able to take on more than a few of the other powers simultaneously. NO one.)

For their troubles, they are usually pilloried by those all about them, particularly by up and coming powers who want their “place in the sun” – the Soviet Union and China being the stand-out examples. (Though there is a lot of whinging from old allies like France). For the last forty years (since Vietnam, and certainly since Gulf War One), there have been signs that the US voter is having serious second thoughts about the whole concept.

Britain was quite reluctant to take over later imperial dependencies, particularly leftover states of defeated Empires like Turkey, such as Iraq and Palestine: but also parts of Africa and Asia “of interest to no bugger”. They were never part of the British ideal of commercial empire, and were almost impossible to govern. They were abandoned as soon as possible.

The United States is currently experiencing the joys of taking over, or being responsible for unwanted bits of empire. Strangely the names Iraq and Palestine are occurring on that list, as well as Afghanistan and possibly other commitments to come. (The US has interfered in these areas far longer than Britain had before she was stuck with them). They cannot be considered part of a logical geopolitical empire (not even for oil conspiracy nuts), and will be abandoned as soon as possible.

The British voter responded to the world wars by wanting out of empire. Now. Some of the states thus “released” were well-developed societies with decent infrastructure and good literacy and rule of law concepts. India, Malta, Ceylon, Bermuda and Singapore spring to mind. Others were abandoned prematurely: without literacy, rule of law, good infrastructure, a developed civil service, practice of voting, or any of the other minor necessities for establishing a democratic state. See any list of African dictatorships.

The US voter is responding to current events by wanting out of the Middle East ASAP. They are intent on abandoning states to “democracy”, regardless of a lack of literacy, rule of law, good infrastructure, a developed civil service, practice of voting, or any of the other minor necessities for establishing a democratic state. Whoops.

Britain suffered from an immense artificial economic high after the Napoleonic war. This left the British economy extremely artificially inflated for eighty years, and still well above its realistic weight in the world for another fifty (and only really brought back to the field by the immense economic losses of two world wars). In the last twenty years Britain has held a more realistic place in the world economy for its population and industrial level (though still relatively inflated by an immense backlog of prestige and sometimes reluctant respect.).

The US suffered from an immense artificial economic high after WWII. This left the US economy artificially inflated for the rest of the century, and still well above its realistic weight in the world to the present. … Sometime in the next few decades, the US will probably return to a more realistic place in the world economy for its population and industrial level. (Minor variables like World War III may make this projection uncertain as to actual timing, but it will happen: simply because the US will not be able to largely sit out most of the next world wars and profiteer from everyone else’s ruin the way she could in the last two).

Nigel Davies, “The Empires of Britain and the United States – Toying with Historical Analogy”, rethinking history, 2009-01-10.

October 19, 2022

Luxury beliefs in action

In The Critic, Sebastian Milbank looks at the young vandals, er “activists” who decided that throwing soup on a famous painting was a totally sensible and reasonable thing to do in order to direct our attention to their luxury beliefs:

On Friday Phoebe Plummer, a 21-year-old graduate student and activist, threw a tin of soup over a Van Gogh painting in the National Gallery, before proceeding to glue herself to the wall. “What is worth more, art or life?” she shouted in a manner reminiscent of an especially tiresome student at the Oxford Union. Whilst Phoebe didn’t exactly make it to Oxford, she was the beneficiary of a £15,000 a year boarding school education. Having rich parents probably helps if your lifestyle involves dying your hair pink, covering yourself in glitter and getting glued to a succession of defaced public monuments. The legal fees alone must be a headache.

That said, perhaps the organisation she cheerfully acts in the name of — Just Stop Oil — can foot the bills. After all, it’s a registered charity funded by the US-based organisation The Climate Emergency Fund. The Fund boasts on its website that “We provide a safe and legal means for donors to support disruptive protest that wakes up the public and puts intense pressure on lawmakers”, not to mention “Our robust legal team”. The charity comes with endorsements by high profile organisations such as fashion magazine Marie Claire and the backing of donors like the group’s co-founder, oil heiress Aileen Getty who is quoted as saying, “Don’t we have responsibility to take every means to protect the Earth”.

I can think of other organisations that provide “A safe harbour for donors” and put “intense pressure on lawmakers”, not to mention having “robust legal teams” — though they generally feature rather more Italian accents and bodies dumped in the river, and rather fewer celebrity endorsements (Frank Sinatra could not be reached for comment).

The Just Stop Oil organisation itself is even more explicit about its willingness to countenance potentially illegal means. In its FAQ section it calls for people to “use tactics such as strikes, boycotts, mass protests and disruption to withdraw their cooperation from the state”, and announces that they “are willing to take part in Nonviolent direct action targeting the UK’s oil and gas infrastructure should the Government fail to meet our demand by 14 March 2022”. Well the date has past. “Will there be arrests?” the next section asks. The answer? “Probably”.

Quite why organisations that openly fund illegal — sorry “disruptive” — protest, and hire teams of lawyers to avoid the legal consequences, are allowed to enjoy charitable status, let alone avoid investigation by the authorities, is beyond me. Nor is it clear to me how attacks on works of art, or stopping traffic in the road, can attract support for environmental causes, or challenge those who profit from ecological destruction.

The answer lies with the nature of the radical environmental movement, which is often starkly at odds with many of the finest traditions of ecological and anti-industrial thought. Early critics of industrial capitalism like Ruskin and Morris were as concerned with the protection of traditional culture as they were with the destruction of the natural world. Their humanist challenge to industrialism was to call for the return of craft, the embrace of localism, a built environment on a human scale, and an economy that fed the spiritual as well as material needs of mankind.

Theodore Dalrymple on the mindset of the perps:

Youth is often said to be an age of idealism, but if my recollection of my own youth is accurate, it could also be characterized as an age of self-righteousness liberally dosed with hypocrisy, at least when it has known no real hardship that isn’t of its own making.

The two girls who threw a tin of soup at a Van Gogh in the National Gallery in London and then glued themselves to the wall certainly evinced a humorless self-righteousness and self-importance: indeed, they seemed almost to secrete it as a physiological product. They were part of a movement of dogmatic and indoctrinated young people called Just Stop Oil that’s currently making a public nuisance of itself in this fashion in Britain, holding up traffic and causing misery to thousands, in what it believes to be the best of all good causes, saving the planet.

[…]

Youth suffers from both fevered over-imagination and a complete absence of imagination. This is the natural consequence of a lack of experience of life, in which limited experience is taken as the total of all possible human experience. Youth accepts uncritically its own wildest projections and doesn’t know the limitations of its own knowledge. It believes itself endowed with moral purity and allows for no ambiguity, let alone tragic choice. It’s sure of itself.

The young women who threw soup at the Van Gogh probably didn’t know that, even if the man-made climate change hypothesis were wholly correct, they lived in a country that produced about 1 to 2 percent of the alleged greenhouse gases in the world, so that even if their action put a complete end to that contribution (a most unlikely outcome) it would make absolutely no difference whatever to the fate of the planet. Their action certainly caused the public irritation and expense, and its most likely long-term outcome is a costly increase in surveillance and security at the gallery because the two of them were able to do what they did with such ease.

However, they were probably dimly aware, or had the good sense to know, that it would have been inadvisable for them to make their gesture in some country responsible for a far greater proportion of the alleged causation of climate change than their own—China, for example. Cowardice, after all, is the better part of self-righteousness.

September 20, 2022

Pierre Poilievre and the role of the Governor of the Bank of Canada

In The Line, Jen Gerson looks at new Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre’s threat to fire the head of the Bank of Canada if and when he becomes Prime Minister:

Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre at a Manning Centre event, 1 March 2014.

Manning Centre photo via Wikimedia Commons.

In May, Poilievre claimed that Macklem was “surrendering his independence” to the government of the day by using quantitative easing — printing money — to ease the COVID economic crisis. During the party’s English-language debate in Edmonton, Poilievre also said he would fire the governor if he ascended to prime minister.

This, very rightly, ticked off a lot of people. The governor of the Bank of Canada ought to be independent of daily partisan machinations for very good reason; we don’t want the person setting inflation targets to be subject to political pressure, otherwise we would risk a lot more money printing to pay for social programs in the short term, and devaluation of our currency in the long term. So threatening to fire the governor because he or she failed to hew to an incoming government’s wishes is a bad idea. We want that person to stay above the partisan fray.

A Conservative ought to understand this better than most.

Further, much of our inflationary woes is the result of international supply chain issues, which is something beyond the governor’s control. The bank’s defenders have been quick to make this point. Looking at overall increase in the monetary supply, including the significant amounts of money that was pumped into the economy for pandemic relief measures, in addition to the thwack of cash sitting on the banks’ books in the form of potential debt, I suspect that this argument is still highly debatable.

Regardless, the response to Poilievre’s comments from the bank itself was interesting. Although he didn’t call for the firing of his boss, Paul Beaudry, the deputy governor of the Bank conceded that Poilievre had at least a smidgen of a point.

“The aspect that we should be held accountable is exactly right,” Beaudry told a news conference in June. “Right now we completely understand that lots of Canadians can be frustrated at the situation,” he said. “It’s difficult for a lot of people. And we haven’t managed to keep inflation at our target, so it’s appropriate [that] people are asking us questions.”

Macklem himself acknowledged that he had misjudged the possibility for a serious inflationary period back in April. He deserves praise for admitting this! It’s difficult for people in senior roles to admit they were wrong and seek to course correct. One might even argue that his humility on this point demonstrates a personality that is particularly well-suited for his role.

So I want to reiterate that I think threatening to fire Tiff Macklem is a bad idea. It directly undermines the independence of his office, and it places blame on the bank for inflation, when the causes of that inflation are, at best, not his fault, and at worst, still not perfectly understood.

That said — again, messing with the independence of the bank is bad, m’kay — there is a historical precedent for this kind of institution-meddling chicanery. The last politician to threaten an unpopular Bank of Canada governor for political gain was that notable far-right populist … Jean Chrétien. That was back in 1993, in a situation that almost perfectly mirrors the economic and political dynamics of today.

In the ’90s, the incumbent Conservatives had appointed Bank of Canada governor John Crow, who had set interest rates to about seven per cent in order to keep inflation in check. If that figure, which is closer to historical norms than we like to remember, makes you eye your mortgage renewals a little warily, so it should. The Liberals, who were gunning to take over the government from the Conservatives, had argued that Crow’s obsession on maintaining low inflation had worsened a recession; they wanted Crow to prioritize reducing Canada’s unemployment rate instead.

Of course, if that sounds like a potential prime minister taking swipes at an ostensibly independent agent of the Bank of Canada, well, that’s because that’s exactly what it was. And media at the time recognized this at the time.

I think this is another case of a politician indulging in a bit of “bad policy but good politics” rhetoric. Unless he actually means it…

September 17, 2022

In the wake of the Russo-Ukrainian war, Europe’s cold winter looms ahead

Andrew Sullivan allows his views on the fighting in Ukraine to be a bit more optimistic after Ukrainian gains in the most recent counter-attacks on Russian-held territory around Kharkiv:

Approximate front-line positions just before the Ukrainian counter-attack east of Kharkiv in early September 2022. The MOD appears to have stopped posting these daily map updates sometime in the last month or so (this is the most recent as of Friday afternoon).

As we were going to press last week — I still don’t know a better web-era phrase for that process — Ukraine mounted its long-awaited initiative to break the military stalemate that had set in after Russia’s initial defeat in attempting a full-scale invasion. The Kharkiv advance was far more successful than anyone seems to have expected, including the Ukrainians. You’ve seen the maps of regained territory, but the psychological impact is surely more profound. Russian morale is in the toilet — and if it seems a bit premature to say that Ukraine will soon “win” the war, it’s harder and harder to see how Russia doesn’t lose it. By any measure, this is a wonderful development — made possible by Ukrainian courage and Western arms.

Does this change my gloomy assessment of Putin’s economic war on Europe, which will gain momentum as the winter drags on? Yes and no. Yes, it will help shore up nervous European governments who can now point to Ukraine’s success to justify the coming energy-driven recession. No, it will not make that recession any less intense or destabilizing. It may make it worse, as Putin lashes out.

More to the point, the Kharkiv euphoria will not last forever. September is not next February. Russia still has plenty of ammunition to throw Ukraine’s way (even if it has to scrounge some from North Korea); it is still occupying close to a fifth of the country; still enjoying record oil revenues; has yet to fully mobilize for a war; and still has China and much of the developing world in (very tepid) acquiescence. Putin is very much at bay. But he is not finished.

Europe’s scramble to prevent mass suffering this winter is made up of beefing up reserves (now 84 percent full, ahead of schedule), energy rationing, government pledges to cut gas and electricity use, nationalization of gas companies, and billions in aid to consumers and industry, with some of the money recouped by windfall taxes on energy suppliers. The record recently is cause for optimism:

The Swedish energy company Vattenfall AB said industrial demand for gas in France, the U.K., the Netherlands, Belgium and Italy is down about 15% annually.

But the use of gas by households is trivial in the summer in Europe compared with the winter — and subsidizing the cost doesn’t help conservation. Russia will now cut off all gas — which could send an economy like Italy’s to contract more than 5 percent in one year. There really is no way out of imminent, deep economic distress across the continent. Even countries with minimal dependence on Russia, like Britain, are locked into an energy market with soaring costs.

That will, in turn, strengthen some of the populist-right parties — see Italy and Sweden. The good news is that the new right in Sweden backs NATO, and Italy’s post-liberal darling, Georgia Meloni, who once stanned Putin, “now calls [him] an anti-Western aggressor and said she would ‘totally’ continue to send offensive arms to Ukraine”. The growing evidence of the Russian army’s war crimes — another mass grave was just discovered in Izyum — makes appeasement ever more morally repellent.

So what will Putin do now? That is the question. His military is incapable of recapturing lost territory anytime soon; he is desperate for allies; and mobilizing the entire country carries huge political risks. It’s striking to me that in a new piece, Aleksandr Dugin, the Russian right’s guru, is both apoplectic about the war’s direction and yet still rules out mass conscription:

Mobilization is inevitable. War affects everyone and everything, but mobilization does not mean forcibly sending conscripts to the front, this can be avoided, for example, by forming a fully-fledged volunteer movement, with the necessary benefits and state support. We must focus on veterans and special support for the Novorossian warriors.

This is weak sauce — especially given Dugin’s view that the West is bent on “a war of annihilation against us — the third world war”. It’s that scenario that could lead to a real and potentially catastrophic escalation — which may be why the German Chancellor remains leery of sending more tanks to Ukraine. The danger is a desperate Putin doing something, well, desperate.

I have no particular insight into intra-Russian arguments over mobilization, but there seems to be zero point (other than for propaganda … and that cuts both ways) to instituting a “Great Patriotic War”-style mass conscription drive at this point. The Russian army could absolutely be boosted to vast numbers through conscription. Vast numbers of untrained, unwilling young people with little military training and no particular passion to save the Rodina this time, despite constant regime callbacks to desperate struggle against Hitler in 1941-45. Pushing under- or untrained troops into battle against a Ukrainian army equipped with relatively modern western weaponry would be little more than deliberate slaughter and I can’t believe even Putin would be that reckless.

July 28, 2022

“… this time it will be worldwide”

Elizabeth Nickson recounts her journey from dedicated environmentalist to persecuted climate dissident and explains why so many of us feel as if we’re living on the slopes of a virtual Vesuvius in 79AD:

A screenshot from a YouTube video showing the protest in front of Parliament in Ottawa on 30 January, 2022.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

I was experiencing a time-worn campaign to shut down a voice that conflicted with an over-arching agenda. And in the scheme of things, I was nothing. But in fact, I was almost the only one, everyone else had been chased out. I was an easy kill, required few resources. It was personal, it was vicious beyond belief, and it had nothing to do with truth. If I had continued my work in newspapers, they would have attacked my mother and my brothers, two of the three of whom were fragile.

As of now, this has happened to hundreds of thousands of people in every sector of the economy. The chronicles of the cancelled are many and varied, and they all start with the furies, unbalanced, easily triggered and marshalled to hunt down and kill an enemy. These programs, pogroms, are meticulously planned, they analyze you, find your weakness, and attack it. In my case, it was my solitude, my income, my need to look after my family that made me an easy sacrifice.

I was such an innocent. I thought with my hard-won skills, my ability to reason, to number crunch, to apply economic theory and legit charting, and report, the truth would be valuable, useful.

Every single member of the cancelled has had their faith in the culture badly shaken. They all thought, as I did, that we were in this together, we needed the truth in order to make good decisions, decisions that would promote the good of all.

Not now. Not anymore.

The truth I found behind the fields and forests of the natural world is animating people on the streets in Europe today, the Dutch, French and German farmers. It animated the revolution in Sri Lanka.

Because what I and hundreds of others had found was censored, the destructive agenda has advanced to the point where their backs are against the wall. They don’t have a choice. They have to win. And they are in the millions.

Same with Trump’s people. They aren’t mindless fans or acolytes or sub-human fools. Their backs are against the wall. They have no choice but to fight.

But because I and the many like me, who know what happened, were shut down, disallowed from writing about it, cancelled and vilified, no one understands why this is happening in any depth. City people mock and hate rural people. My photographer colleague/best friend in New York: “racists as far as the eye can see”. My old aristocratic bf London: “Pencil neck turkey farmers”. No city person can take on board that they have allowed legislation and regulation which is destroying the rural economy because they have been brainwashed by the hysteria in the environmental movement. This destruction is not the only reason but it is the fundamental reason for our massive debts and deficits. The base of the economy has been destroyed. We have lost two decades of real growth.

And we did it via censorship.

There is a truism about revolutions in China. All of a sudden, across this great and massive country with its five thousand year culture, people put down their tools and start marching towards the capital, hundreds of millions all at once.

We are almost there. But this time it will be worldwide.

June 8, 2022

The Climate Wars are dead, merely collateral damage from the Russia-Ukraine War

JoNova links to this Foreign Policy article by Ted Nordhous, signfiying the end of a “lame Cold War substitute” as the conflict in Ukraine pushes it decisively off the agenda for most western nations:

Four days after Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine, the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released its latest assessment of the impacts of global warming. Leading media outlets did their best to pick out the most dire scenarios and findings from the report. But the outbreak of the first major European war since 1945 kept the report off the front page or, at the very least, below the fold. “Climate Change Is Harming the Planet Faster Than We Can Adapt” simply couldn’t compete with “Putin Is Brandishing the Nuclear Option”.

Meanwhile, the headlong rush across Western Europe to replace Russian oil, gas, and coal with alternative sources of these fuels has made a mockery of the net-zero emissions pledges made by the major European economies just three months before the invasion at the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland. Instead, questions of energy security have returned with a vengeance as countries already struggling with energy shortages and price spikes now face a fossil fuel superpower gone rogue in Eastern Europe.

In the decades following the end of the Cold War, global stability and easy access to energy led many of us to forget the degree to which abundant energy is existential for modern societies. Growing concern about climate change and the push for renewable fuels also led many to underestimate just how dependent societies still are on fossil fuels. But access to oil, gas, and coal still determines the fate of nations. Two decades of worrying about carbon-fueled catastrophes — and trillions of dollars spent globally on transitioning to renewable power — haven’t changed that basic existential fact.

Virtually overnight, the war in Ukraine has brought the post-Cold War era to a close, not just by ending Europe’s long era of peace, but by bringing basic questions of energy access back to the fore. A new era, marked by geopolitically driven energy insecurity and resource competition, is moving climate concerns down on the list of priorities. If there is a silver lining in any of this, it’s that a shift of focus back to energy security imperatives might not be the worst thing for the climate. Given the scant effect international climate efforts have had on emissions over the past three decades, a turn back toward energy realpolitik — and away from the utopian schemes that have come to define climate advocacy and policymaking worldwide — could actually accelerate the shift to a lower-carbon global economy in the coming decades.

The issue of climate change burst into the global debate just as the Cold War was coming to an end. As one existential threat seemingly receded, another came into view. For much of the international community, particularly the United Nations and its agencies, climate change also became much more than an environmental issue, offering an opportunity to reshape the post-Cold War order to be more equitable, multilateral, and politically integrated.

Nonetheless, when the framework for climate action emerged in the early 1990s, it built on the experience of the Cold War era. U.S.-Soviet arms control agreements became the model for global cooperation on climate change. Just as the superpowers had signed treaties to gradually draw down their nuclear weapons stocks, nations would commit to draw down their emissions. Yet the first major agreement to propose legally binding limits on emissions — the 1997 Kyoto Protocol — was dead from the moment the U.S. Senate unanimously rejected its terms, even before the negotiations had been finalized. Combine U.S. opposition with the understandable reluctance of energy-hungry, fast-developing nations such as China and India to even consider limiting emissions, and the inefficacy of international climate action was set.

June 2, 2022

“Like many problems in American history, recycling began as a moral panic”

Jon Miltimore recounts the seminal event that kicked off the recycling pseudo-religion in North America:

The frenzy began in the spring of 1987 when a massive barge carrying more than 3,000 tons of garbage — the Mobro 4000 — was turned away from a North Carolina port because rumor had it the barge was carrying toxic waste. (It wasn’t.)

“Thus began one of the biggest garbage sagas in modern history,” Vice News reported in a feature published a quarter-century later, “a picaresque journey of a small boat overflowing with stuff no one wanted, a flotilla of waste, a trashier version of the Flying Dutchman, that ghost ship doomed to never make port.”

The Mobro was simply seeking a landfill to dump the garbage, but everywhere the barge went it was turned away. After North Carolina, the captain tried Louisiana. Nope. Then the Mobro tried Belize, then Mexico, then the Bahamas. No dice.

“The Mobro ended up spending six months at sea trying to find a place that would take its trash,” Kite & Key Media notes.

America became obsessed with the story. In 1987 there was no Netflix, smartphones, or Twitter, so apparently everyone just decided to watch this barge carrying tons of trash for entertainment. The Mobro became, in the words of Vice, “the most watched load of garbage in the memory of man.”

The Mobro also became perhaps the most consequential load of garbage in history.

“The Mobro had two big and related effects,” Kite & Key Media explains. “First, the media reporting around it convinced Americans that we were running out of landfill space to dispose of our trash. Second, it convinced them the solution was recycling.”

Neither claim, however, was true.

The idea that the US was running out of landfill space is a myth. The urban legend likely stems from the consolidation of landfills in the 1980s, which saw many waste depots retired because they were small and inefficient, not because of a national shortage. In fact, researchers estimate that if you take just the land the US uses for grazing in the Great Plains region, and use one-tenth of one percent of it, you’d have enough space for America’s garbage for the next thousand years. (This is not to say that regional problems do not exist, Slate points out.

The widespread imposition of recycling mandates across North America was probably an inevitable reaction to the voyage of the Mobro. For many people, this was the end of the story, as things that were previously just buried in landfill sites would now be safely and efficiently put back into the economy as re-used, re-purposed, or actual recycled products. Win-win, right?

Sadly, the economic case for recycling many items is weak to non-existant. The demand for recycled materials was lower than predicted and often only maintained through subsidies and hidden incentives that couldn’t last forever. Once the incentives went away, so did much of the created demand. Worse, the way a lot of the stream of recyclable materials was handled was by shipping it off to China or certain developing nations — in effect, paying them to take the problem off the hands of western governments. This resulted in even more problems:

Americans who’ve spent the last few decades recycling might think their hands are clean. Alas, they are not. As the Sierra Club noted in 2019, for decades Americans’ recycling bins have held “a dirty secret”.

“Half the plastic and much of the paper you put into it did not go to your local recycling center. Instead, it was stuffed onto giant container ships and sold to China,” journalist Edward Humes wrote. “There, the dirty bales of mixed paper and plastic were processed under the laxest of environmental controls. Much of it was simply dumped, washing down rivers to feed the crisis of ocean plastic pollution.”

It’s almost too hard to believe. We paid China to take our recycled trash. China used some and dumped the rest. All that washing, rinsing, and packaging of recyclables Americans were doing for decades — and much of it was simply being thrown into the water instead of into the ground.

The gig was up in 2017 when China announced they were done taking the world’s garbage through its oddly-named program, Operation National Sword. This made recycling much more expensive, which is why hundreds of cities began to scrap and scale back operations.

April 8, 2022

The structure of the Chinese government

Scott Alexander reviews The Third Revolution, by Elizabeth Economy, although as he says up front, “It’s a look through recent Chinese history, with The Third Revolution as a very loose inspiration.”:

How Does China’s Government Work?

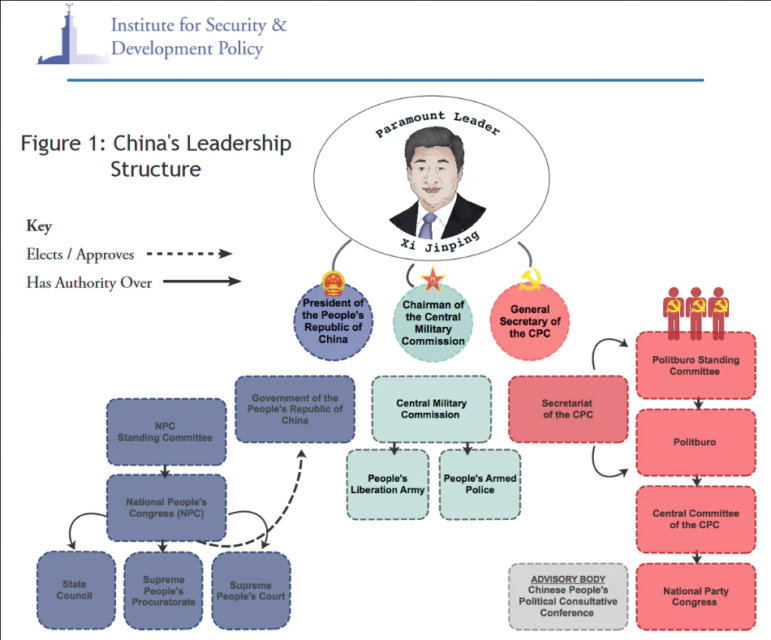

The traditional answer is a flowchart like this one (source):

But you could give a similarly convoluted flowchart for America, and it would tell people much less than words like “democracy” or “balance of powers”. What’s the Chinese equivalent?

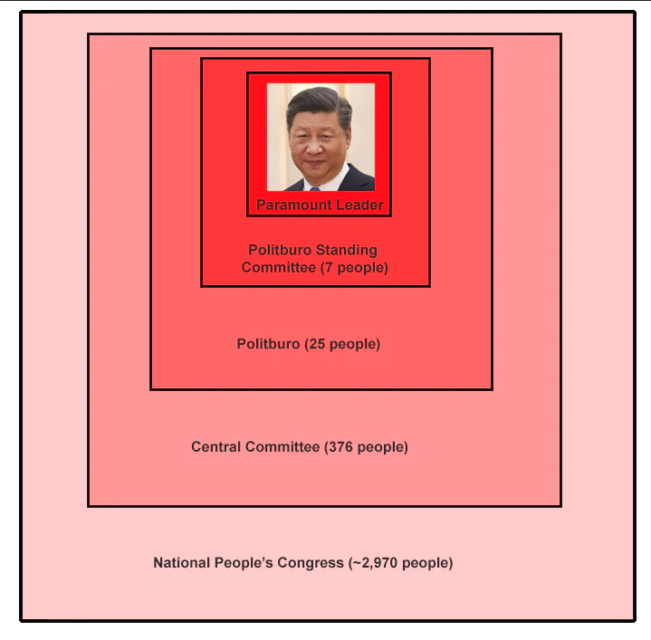

I found it a little more helpful to see it diagrammed it as a series of nested squares:

The inner levels have real power, and the outer layers are theoretically overseers but actually rubber stamps. Things get more and more rubber-stampy as you go out, culminating in the National People’s Congress, which recently voted to re-elect Xi by a vote of 2,970 in favor, 0 against — it’s so irrelevant that it’s literally called “the NPC”.

Who chooses the members of the inner groups? In theory, the outer groups; for example, the Central Committee is supposed to elect the Politburo Standing Committee. In practice, these selections tend to be of the “2,970 in favor, 0 against” variety, so they must be taking marching orders from someone. Who? The Chinese government doesn’t talk about it much, but probably the members of the Politburo Standing Committee hand-pick everyone, including the Paramount Leader and their own successors.

How do they pick? Mostly patron-client relationships. Every leading politician cultivates a network of loyal supporters; if he takes power, he tries to put as many of his people into top posts as he can. The seven Politburo members wheel and deal with each other about whose clients should get which positions, including any unoccupied Politburo seats.

If the two word description of US politics is “democracy, checks-and-balances”, then the two word description of Chinese politics is “oligarchy, patrons-and-clients”. If this seems exotic, it shouldn’t: it’s not much different from how the US fills unelected posts like “ambassador” and “White House staffer”. The Trump presidency put this into especially sharp relief, either because Trump did it more blatantly than usual or just because Trump’s clients were so obviously different from the normal Washington crowd. Consider eg the appointment of Jeff Sessions (among the first Congressmen to endorse Trump) as Attorney General.

In the US, this is a peripheral part of the system, checked by democracy. In China, it’s the whole game.

March 6, 2022

December 29, 2021

October 14, 2021

QotD: Americans’ perception of foreign economic threats

I am old enough to remember when almost everyone believed that the Russians were, as Khrushchev put it, going to “bury” us. Even leading economists such as Paul Samuelson were taken in by such nonsense. Of course, no such burial occurred, because just producing vast quantities of concrete, steel, and H-bombs is no evidence that anything of genuine value is being produced. Later Japan became the Godzilla that was going to eat the U.S. and European economies with its bureaucratic setup for picking and subsidizing “winners.” Before long that setup too collapsed in a heap and gave way to perpetual stagnation. Now almost everyone quakes in his boots while beholding the mighty Chinese economy. Again the hysteria has no firm foundation. An economy shaped and guided by government bureaucrats and Communist bigwigs by means of tariffs, subsidies, state-controlled credit, and state-owned industries cannot be a real growth miracle for long. This too shall pass.

And when it does Americans will learn nothing from their most recent mistake. If people really understood sound economics, they would not continue to make this same mistake again and again.

Robert Higgs, “China — Americans’ Economic Bugaboo du Jour”, The Beacon, 2018-12-19.

October 8, 2021

The case for defending Taiwan

Roberto White explains why the west should help protect the Republic of China from the People’s Republic of China:

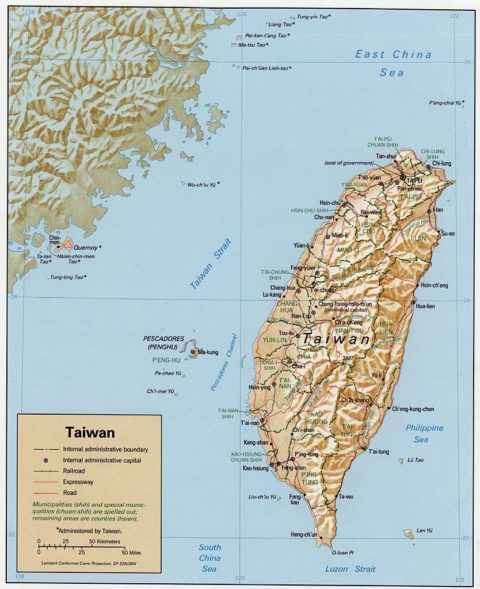

The past few days have seen Taiwan subjected to another wave of continuous harassment by China. Of course this is nothing new; China has violated Taiwan’s airspace since at least 2014. But, on Monday, a record 34 fighter jets were dispatched to Taiwan. Beijing’s increasingly erratic behaviour towards Taiwan brings to the fore why the West must defend them.

Taiwan is a free-market democracy that, despite its overbearing northern neighbour, has managed to create a vibrant economy that ranks as the sixth freest economy in the world. Crucially, it is a major producer of semiconductors (a device that helps power everything from cars to satellites), accounting for 92 per cent of all production of the world’s most sophisticated and important chips. Thus, from both an ideological and strategic standpoint, defending Taiwan is a mutually beneficial move.

The case for Taiwan’s defence is further strengthened when we look at what could happen in Asia should China take Taiwan by force.

With Taiwan’s ports and air bases, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could extend its maritime militia northwards through the Ryukyu (the chain of islands between Taiwan and Japan) and the Senkaku Islands (disputed by China and Japan). This would give China increased leverage over Japan in a time of crisis by, for example, restricting its maritime commerce.

The CCP could further use Taiwan as a base for tighter control of the South China Sea by blocking the Luzon Strait (between Taiwan and the Philippines) and the Balintang channel, which would cut off the traditional route used by the US Navy to navigate regional waters. In essence, China would immediately become the foremost power in the Indo-Pacific that could eventually kick the US and its allies out of the region. Unfortunately, the threat of a Chinese invasion is not a distant reality. In March of this year Admiral Philip Davidson, the United States’ top military officer in the Asia-Pacific, warned that China could invade Taiwan by 2027.

Given the perilous scenario that would emerge from a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, it is vital that, should an invasion happen, the West comes to Taiwan’s defence. However, until such a time, Western allies should aim to help Taiwan by promoting its participation in international forums. The first step would be to allow diplomats and other officials with Taiwanese passports to enter UN buildings, which they currently cannot do. This would most likely provoke a backlash from China, yet it would also confer Taiwan the dignity and respect that officials from every other state have.

The West should also stand firm against Chinese attempts to exclude Taiwan from international organisations. Between 2008-2016, Taiwan was invited to be an observer at the World Health Organization (WHO) under the name “Chinese Taipei”. In 2016, after Tsai Ing-Wen was elected Taiwan’s President, Beijing rescinded the invitation and Taiwan has not been allowed to participate since.